Olivierlejardinier

Jedi Council Member

From here, published 8 Feb 2023 :

"

"This is a truly exciting discovery," said co-author George Lasry, a computer scientist and cryptographer in Israel. "Mary, Queen of Scots, has left an extensive corpus of letters held in various archives. There was prior evidence, however, that other letters from Mary Stuart were missing from those collections, such as those referenced in other sources but not found elsewhere. The letters we have deciphered are most likely part of this lost secret correspondence.” Lasry is part of the multi-disciplinary DECRYPT Project devoted to mapping, digitizing, transcribing, and deciphering historical ciphers.

Mary sought to protect her most private letters from being intercepted and read by hostile parties. For instance, she engaged in what's known as "letter-locking," a common practice at the time to protect private letters from prying eyes. As we've reported previously, Jana Dambrogio, a conservator at MIT Libraries, coined the term "letter-locking" after discovering such letters while a fellow at the Vatican Secret Archives in 2000.

Those "locked" Vatican letters dated back to the 15th and 16th centuries, and they featured strange slits and corners that had been sliced off. Dambrogio realized that the letters had originally been folded in an ingenious manner, essentially "locked" by inserting a slice of the paper into a slit, then sealing it with wax. It would not have been possible to open the letter without ripping that slice of paper—providing evidence that the letter had been tampered with.

Portrait of Mary Stuart c. 1558–1560 at about 17 years old, painted by François Clouet.

Public domain

Queen Elizabeth I, Catherine de Medici, Machiavelli, Galileo Galilei, John Donne, and Marie Antoinette are among the famous personages known to have employed letter-locking for their correspondence. There are hundreds of letter-locking techniques like "butterfly locks," a simple triangular fold-and-tuck, and an ingenious method known as the "dagger-trap," which incorporates a booby-trap disguised as another, simpler type of letter lock. Mary, Queen of Scots, used an intricate spiral letter-lock for her final letter (to King Henri III of France) on the eve of her execution for treason in February 1587. A 1574 letter from Mary also used a variant of the spiral lock.

Mary was well-trained in the art of cipher by her mother, Marie de Guise, from a very young age. The substantial collection of her letters that are housed in various archives contains tantalizing references to other missing letters. John Bossy, author of Under the Molehill: An Elizabethan Spy Story (2002), suggested that these missing letters might have been written in cipher to Mary's extensive network of associates and allies—a network that was fatally compromised around mid-1583 by Sir Francis Walsingham (Elizabeth I's spymaster), eventually leading to Mary's trial and execution for treason. Like many before him, Bossy assumed those letters had been lost.

Enter Lasry and his fellow code-breaking enthusiasts: physicist and patents expert Satoshi Tomokiyo and pianist and music professor Norbert Biermann. As part of DECRYPT, they were scouring various archives for documents encrypted with ciphers, particularly documents that had not yet been attributed. They stumbled upon several collections at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France's online archives, identifying 57 documents fully written in cipher. Other items in the collection dated from the 1520s and 1530s and were primarily concerned with "Italian affairs." None of the text in the letters was written in clear language, so it wasn't possible to determine who wrote them without first deciphering them.

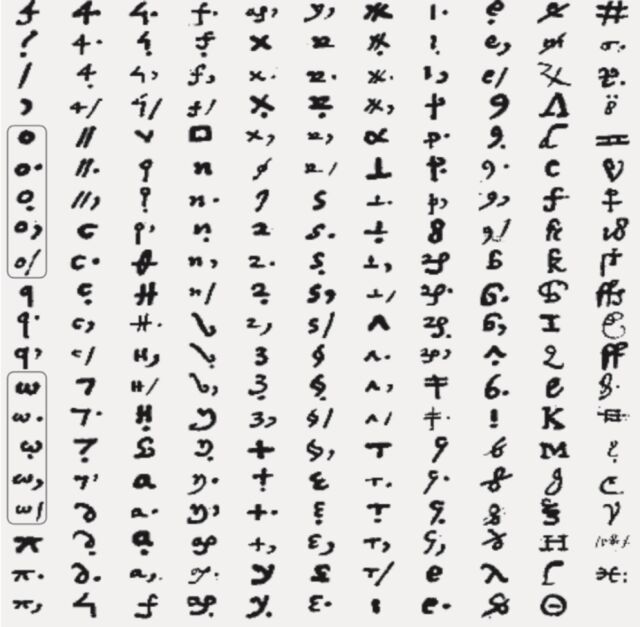

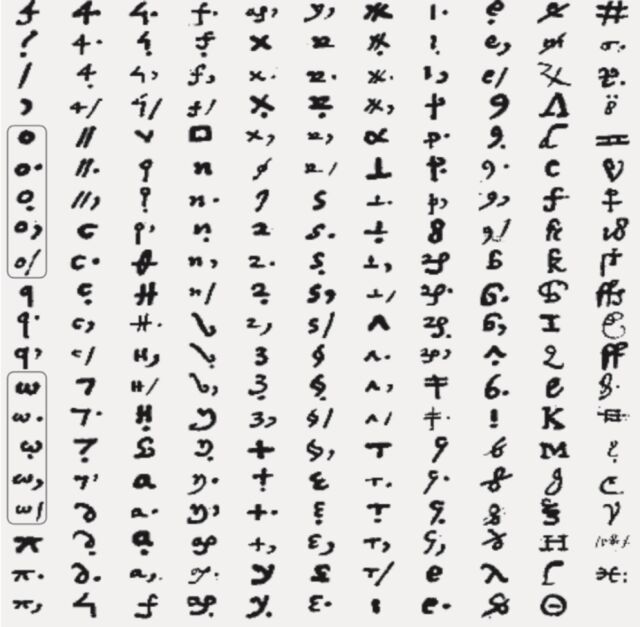

Full set of graphical symbols.

Lasry/Biermann/Tomokiyo

Lasry et al. did just that, relying on a combination of computerized cryptanalysis, manual code-breaking, and linguistic and contextual analysis. The documents contained only graphical symbols (more than 150,000 in total), requiring the team to rely on a specially developed graphical user interface (GUI) tool. There was a considerable amount of back-and-forth effort, but first they transcribed a few documents and conducted an initial analysis and decipherment, which revealed that the documents had not been written in Italian (as previously assumed) but in French. The next step involved identifying the special symbols (homophones) and the overall structure of the cipher.

Those partial decipherments enabled Lasry et al. to conclude that the letters had been written by Mary, Queen of Scots, to the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau. There were already several known letters between the two, so Lasry and his co-authors were able to find some that matched their deciphered material, thereby validating the meaning of several other symbols. They were then able to identify the symbols for names, places, and the twelve months of the year.

All that work allowed them to decrypt the most challenging passages in the letters—puzzling because they seemed to be riddled with spelling errors or were unintelligible, thanks to the use of several different cipher tables designed for different recipients. The final fully recovered cipher table turned out to be quite similar to other ciphers used during this period—including the cipher Mary used to communicate with Guillaume de l'Aubespine de Châteauneuf, who succeeded Castelnau as French ambassador.

"Upon deciphering the letters, I was very, very puzzled, and it kind of felt surreal,” said Lasry. “We have broken secret codes from kings and queens previously, and they’re very interesting, but with Mary, Queen of Scots, it was remarkable as we had so many unpublished letters deciphered and because she is so famous. Together, the letters constitute a voluminous body of new primary material on Mary Stuart—about 50,000 words in total, shedding new light on some of her years of captivity in England."

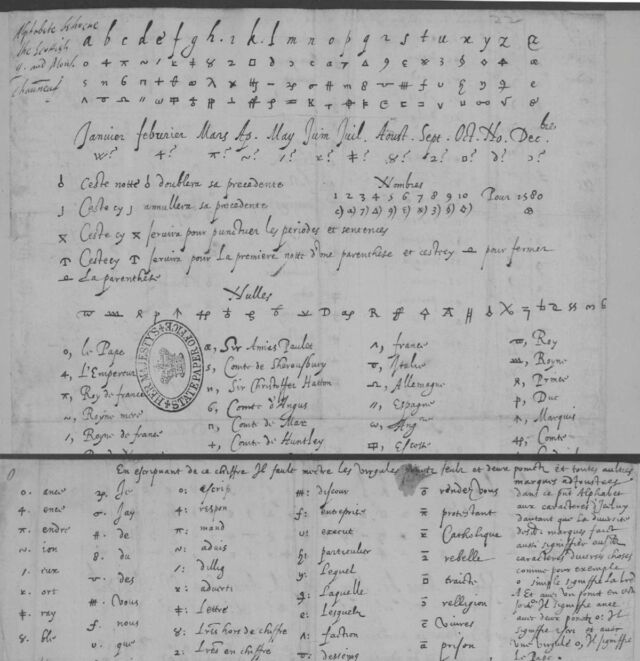

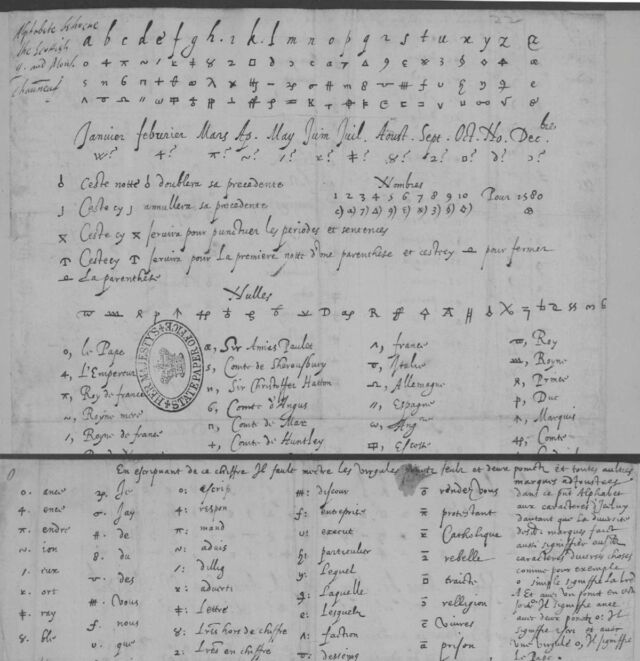

Selected parts of a cipher between Mary and Chateauneuf, the French ambassador who succeeded Castelnau, used for comparison.

Bibliotheque nationale de France

Of the 57 letters, 54 were addressed to Castelnau, and all are written between May 1578 and May 1584. (One partially enciphered letter was dated October 30, 1584.) Taken together with known letters already preserved in archives, Lasry et al. broke Mary's correspondence into five distinct periods. There are relatively few letters in the inventory dated between 1576-1579, including four of the newly deciphered letters. Eleven of the newly decoded letters date between 1580-1581.

By 1582, Mary clearly had established a stable secret communication channel with Castelnau, relying on several trusted couriers, so far more letters were exchanged, including 29 of the newly decoded letters. By mid-1583, Walsingham had recruited a mole in the French embassy who passed on leaked copies of Mary's correspondence with Castelnau. The authors noted that seven of the eight newly decoded letters turned out to have plaintext copies preserved in British archives, adding, "It would seem that the leak from the embassy was quite effective and comprehensive." That would explain why there were no coded letters written to Castelnau between 1585-1586.

As for topics, Mary wrote frequently about keeping their communication channel secure so that she could maintain her network of allies in France. The two also discussed a proposed marriage between Elizabeth I and the Duke of Anjou, with Mary warning Castelnau "that the English side is not sincere in their negotiations, their only purpose being to weaken France and counter Spain," the authors wrote. (Elizabeth never married.) Mary also accuses the Earl of Leicester and others of plotting against her and accuses Elizabeth of not negotiating for Mary's release in good faith. She describes Walsingham as "a cunning person, falsely offering his friendship while concealing his true intentions," per the authors. "She warns [Castelnau]—rightly—that some people working for her might be Walsingham's agents."

The authors believe that examining other collections in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and other archives might unearth even more enciphered letters, especially since Lasry et al. only had access to digitized online material. In addition, their paper only includes fully deciphered text for a handful of the letters, given the sheer amount of the material (some 50,000 words).

“In our paper, we only provide an initial interpretation and summaries of the letters. A deeper analysis by historians could result in a better understanding of Mary’s years in captivity,” said Lasry. “It would also be great, potentially, to work with historians to produce an edited book of her letters deciphered, annotated, and translated.”

"

Lost and found: Codebreakers decipher 50+ letters of Mary, Queen of Scots

The cache of letters sheds new light on Mary Stuart's years of captivity in England.

An international team of code-breakers has successfully cracked the cipher of over 50 mysterious letters unearthed in French archives. The team discovered that the letters had been written by Mary, Queen of Scots, to trusted allies during her imprisonment in England by Queen Elizabeth I (her cousin)—and most were previously unknown to historians. The team described in a new paper published in the journal Cryptologia how they broke Mary's cipher, then decoded and translated several of the letters. The publication coincides with the anniversary of Mary's execution on February 8, 1587."This is a truly exciting discovery," said co-author George Lasry, a computer scientist and cryptographer in Israel. "Mary, Queen of Scots, has left an extensive corpus of letters held in various archives. There was prior evidence, however, that other letters from Mary Stuart were missing from those collections, such as those referenced in other sources but not found elsewhere. The letters we have deciphered are most likely part of this lost secret correspondence.” Lasry is part of the multi-disciplinary DECRYPT Project devoted to mapping, digitizing, transcribing, and deciphering historical ciphers.

Mary sought to protect her most private letters from being intercepted and read by hostile parties. For instance, she engaged in what's known as "letter-locking," a common practice at the time to protect private letters from prying eyes. As we've reported previously, Jana Dambrogio, a conservator at MIT Libraries, coined the term "letter-locking" after discovering such letters while a fellow at the Vatican Secret Archives in 2000.

Those "locked" Vatican letters dated back to the 15th and 16th centuries, and they featured strange slits and corners that had been sliced off. Dambrogio realized that the letters had originally been folded in an ingenious manner, essentially "locked" by inserting a slice of the paper into a slit, then sealing it with wax. It would not have been possible to open the letter without ripping that slice of paper—providing evidence that the letter had been tampered with.

Portrait of Mary Stuart c. 1558–1560 at about 17 years old, painted by François Clouet.

Public domain

Queen Elizabeth I, Catherine de Medici, Machiavelli, Galileo Galilei, John Donne, and Marie Antoinette are among the famous personages known to have employed letter-locking for their correspondence. There are hundreds of letter-locking techniques like "butterfly locks," a simple triangular fold-and-tuck, and an ingenious method known as the "dagger-trap," which incorporates a booby-trap disguised as another, simpler type of letter lock. Mary, Queen of Scots, used an intricate spiral letter-lock for her final letter (to King Henri III of France) on the eve of her execution for treason in February 1587. A 1574 letter from Mary also used a variant of the spiral lock.

Mary was well-trained in the art of cipher by her mother, Marie de Guise, from a very young age. The substantial collection of her letters that are housed in various archives contains tantalizing references to other missing letters. John Bossy, author of Under the Molehill: An Elizabethan Spy Story (2002), suggested that these missing letters might have been written in cipher to Mary's extensive network of associates and allies—a network that was fatally compromised around mid-1583 by Sir Francis Walsingham (Elizabeth I's spymaster), eventually leading to Mary's trial and execution for treason. Like many before him, Bossy assumed those letters had been lost.

Further Reading

Mary, Queen of Scots, sealed her final missive with an intricate spiral letterlockEnter Lasry and his fellow code-breaking enthusiasts: physicist and patents expert Satoshi Tomokiyo and pianist and music professor Norbert Biermann. As part of DECRYPT, they were scouring various archives for documents encrypted with ciphers, particularly documents that had not yet been attributed. They stumbled upon several collections at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France's online archives, identifying 57 documents fully written in cipher. Other items in the collection dated from the 1520s and 1530s and were primarily concerned with "Italian affairs." None of the text in the letters was written in clear language, so it wasn't possible to determine who wrote them without first deciphering them.

Full set of graphical symbols.

Lasry/Biermann/Tomokiyo

Lasry et al. did just that, relying on a combination of computerized cryptanalysis, manual code-breaking, and linguistic and contextual analysis. The documents contained only graphical symbols (more than 150,000 in total), requiring the team to rely on a specially developed graphical user interface (GUI) tool. There was a considerable amount of back-and-forth effort, but first they transcribed a few documents and conducted an initial analysis and decipherment, which revealed that the documents had not been written in Italian (as previously assumed) but in French. The next step involved identifying the special symbols (homophones) and the overall structure of the cipher.

Those partial decipherments enabled Lasry et al. to conclude that the letters had been written by Mary, Queen of Scots, to the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau. There were already several known letters between the two, so Lasry and his co-authors were able to find some that matched their deciphered material, thereby validating the meaning of several other symbols. They were then able to identify the symbols for names, places, and the twelve months of the year.

All that work allowed them to decrypt the most challenging passages in the letters—puzzling because they seemed to be riddled with spelling errors or were unintelligible, thanks to the use of several different cipher tables designed for different recipients. The final fully recovered cipher table turned out to be quite similar to other ciphers used during this period—including the cipher Mary used to communicate with Guillaume de l'Aubespine de Châteauneuf, who succeeded Castelnau as French ambassador.

"Upon deciphering the letters, I was very, very puzzled, and it kind of felt surreal,” said Lasry. “We have broken secret codes from kings and queens previously, and they’re very interesting, but with Mary, Queen of Scots, it was remarkable as we had so many unpublished letters deciphered and because she is so famous. Together, the letters constitute a voluminous body of new primary material on Mary Stuart—about 50,000 words in total, shedding new light on some of her years of captivity in England."

Selected parts of a cipher between Mary and Chateauneuf, the French ambassador who succeeded Castelnau, used for comparison.

Bibliotheque nationale de France

Of the 57 letters, 54 were addressed to Castelnau, and all are written between May 1578 and May 1584. (One partially enciphered letter was dated October 30, 1584.) Taken together with known letters already preserved in archives, Lasry et al. broke Mary's correspondence into five distinct periods. There are relatively few letters in the inventory dated between 1576-1579, including four of the newly deciphered letters. Eleven of the newly decoded letters date between 1580-1581.

By 1582, Mary clearly had established a stable secret communication channel with Castelnau, relying on several trusted couriers, so far more letters were exchanged, including 29 of the newly decoded letters. By mid-1583, Walsingham had recruited a mole in the French embassy who passed on leaked copies of Mary's correspondence with Castelnau. The authors noted that seven of the eight newly decoded letters turned out to have plaintext copies preserved in British archives, adding, "It would seem that the leak from the embassy was quite effective and comprehensive." That would explain why there were no coded letters written to Castelnau between 1585-1586.

As for topics, Mary wrote frequently about keeping their communication channel secure so that she could maintain her network of allies in France. The two also discussed a proposed marriage between Elizabeth I and the Duke of Anjou, with Mary warning Castelnau "that the English side is not sincere in their negotiations, their only purpose being to weaken France and counter Spain," the authors wrote. (Elizabeth never married.) Mary also accuses the Earl of Leicester and others of plotting against her and accuses Elizabeth of not negotiating for Mary's release in good faith. She describes Walsingham as "a cunning person, falsely offering his friendship while concealing his true intentions," per the authors. "She warns [Castelnau]—rightly—that some people working for her might be Walsingham's agents."

The authors believe that examining other collections in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and other archives might unearth even more enciphered letters, especially since Lasry et al. only had access to digitized online material. In addition, their paper only includes fully deciphered text for a handful of the letters, given the sheer amount of the material (some 50,000 words).

“In our paper, we only provide an initial interpretation and summaries of the letters. A deeper analysis by historians could result in a better understanding of Mary’s years in captivity,” said Lasry. “It would also be great, potentially, to work with historians to produce an edited book of her letters deciphered, annotated, and translated.”

Mary, Queen of Scots wiki

Her Own Words

"En ma Fin gît mon Commencement..." This is the saying which Mary embroidered on her cloth of estate whilst in prison in England and is the theme running through her life. It symbolises the eternity of life after death and Mary probably drew her inspiration from the emblem adopted by her grandfather-in-law, François I of France: the salamander. The Salamander self-ignites at the end of its life, and then rises up from the ashes re-born..."In my End is my Beginning..." |