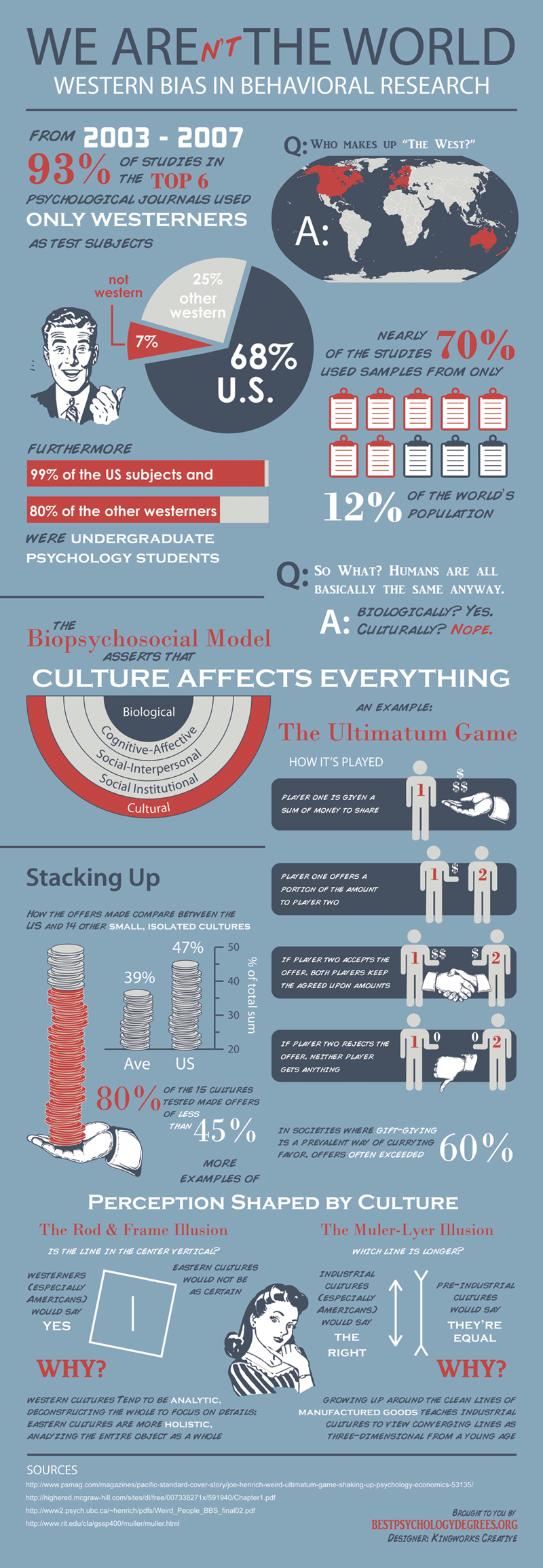

The research by the authors highlight studies which point towards the difference of the WEIRD (Western Educated Industrialized Rich and Democratic) population which predominates samples in social and behavioral psychology. This is an important factor to keep in mind when generalizing the applicability of these studies.

Some more interesting highlights from the paper:

[quote author=Weirdest People in the World]

Americans stand out relative to Westerners for phenomena that are associated with independent self‐concepts and individualism. A number of analyses, using a diverse range of methods, reveal that Americans are, on average, the most individualistic people in the world (e.g., Hofstede 1980, Lipset 1996, Morling & Lamoreaux 2008, Oyserman et al. 2002). The observation that the U.S. is especially individualistic is not new, and dates at least as far back as Toqueville (1835). The unusually individualistic nature of Americans may be caused by, or reflect, an ideology that particularly stresses the importance of freedom and self‐sufficiency, as well as various practices in education and child‐rearing that may help to inculcate this sense of autonomy. American parents, for example, were the only ones in a survey of 100 societies who created a separate room for their baby to sleep (Burton & Whiting 1961, also see Lewis 1995), reflecting that from the time they are born, Americans are raised in an environment that emphasizes their independence (on unusual nature of American childrearing, see Lancy 2009, Rogoff 2003).

The extreme individualism of Americans is evident on many demographic and political measures. In American Exceptionalism, sociologist Seymour Lipset (1996) documents a long list of the ways that Americans are unique in the Western world. At the time of Lipset’s surveys, compared with other Western industrialized societies, Americans were found to be the most patriotic, litigious, philanthropic, and populist (they have the most positions for elections and the most frequent elections, although they have among the lowest turnout rates). They were also among the most optimistic, and the least class‐conscious. They were the most churchgoing in Protestantism, and the most fundamentalist in Christendom, and were more likely than others from Western industrialized countries to see the world in absolute moral terms. In contrast to other large Western industrialized societies, the US had the highest crime rate, the longest working hours, the highest divorce rate, the highest rate of volunteerism, the highest percentage of citizens that went on to post‐secondary education, the highest productivity rate, the highest GDP, the highest poverty rate, the highest income inequality rate, and were in the least support of various governmental interventions. The U.S. is the only industrialized society that never had a viable socialist movement, and was the last country to get a national pension plan, unemployment insurance, accident insurance, and remains the only industrialized nation that does not have a general allowance for families or a national health insurance plan. In sum, there’s some reason to suspect that Americans might be different from other Westerners, as Tocqueville noted.

Given the centrality of self‐concept to so many psychological processes, it follows that the unusual emphasis on American individualism and independence would be reflected in a wide spectrum of self‐related phenomena. For example, self‐concepts are implicated when people make choices (e.g., Vohs et al. 2008). While Westerners tend to value choices more than non‐Westerners (e.g., Iyengar & DeVoe 2003), Americans value making choices more still, and prefer more opportunities, than do those from elsewhere (Savani et al. in press). For example, in a survey of people from six Western countries, only Americans would prefer a choice from 50 different ice cream flavors compared with 10 different flavors. Likewise, Americans (and Britons) prefer to have more choices on menus from upscale restaurants than do those from other European countries (Rozin et al. 2006). The array of choices available, and people’s motivation to make such choices, are even more extreme in the U.S. compared to the rest of the West.

[/quote]

However, there are some significant differences between Americans as well. In present times, college educated Americans seem to differ from other Americans.

[quote author=Weirdest People in the World]

Highly educated Americans differ from other Americans in many important respects. For a number of the phenomena reviewed above in which Americans were identified as global outliers, highly educated Americans occupy an even more extreme position than less educated Americans. These findings are summarized below:

1) Although college‐educated Americans have been found to rationalize their choices in dozens of post‐choice dissonance studies, Snibbe and Markus (2005) found that non‐college educated American adults do not (c.f., Sheth 1970).

[/quote]

College educated Americans are said to have a more pronounced sense of individuality and rationality. When faced with cognitive dissonance after making choices (which are "less than optimal" in the given circumstances), they have a greater tendency to rationalize those choices to keep their self-image intact. This tendency to justify one's choices is universal - as pointed out in "Adaptive Unconscious" but there seems to be important cultural differences. A study called "On the Cultural Guises of Cognitive Dissonance: The Case of Easterners and Westerners" by Hoshino-Browne et al, authors point out that Westerners in general tend to justify their choices more when they made the decision for themselves while Asians tend to rationalize more when they make choices for other people. This observation falls in line with the hypothesis that Westerners in general have a more individual sense of identity while Asians have a more interdependent or collective sense of identity. Consequently, making a sub-optimal or inconsiderate decision for others in the social group affects the Eastern sense of self more than it does when they make a bad choice for themselves.

Continuing about college educated Americans and others

[quote author=Weirdest People in the World]

2) Although Americans are the most individualistic people in the world, American undergraduates score higher on some measures of individualism than do their non‐college educated counterparts, particularly for those aspects associated with self‐actualization, uniqueness, and locus of control (Kusserow 1999, Snibbe & Markus 2005).

3) Conformity motivations were found to be weaker among college‐educated Americans than non‐college‐educated Americans (Stephens et al. 2007), who acted in ways more similar to that observed in East Asian samples (cf., Kim & Markus 1999).

4) Non‐college educated adults are embedded in more tightly‐structured social networks than are college students (Lamont 2000), which raises the question of whether research on relationship formation, dissolution, and interdependence conducted among students will generalize to the population at large.

5) A large study that sampled participants from the general population in Southeast Michigan found that working class people were more interdependent and more holistic than middle class people (Grossmann et al. 2009)

6) The moral reasoning of college‐educated Americans occurs almost exclusively within the ethic of autonomy, whereas non‐college educated Americans use the ethics of community and divinity (Haidt et al. 1993, Jensen 1997). Parallel differences exist in moral reasoning between American liberals and conservatives (Haidt 2007).

7) College‐students (the vast majority of whom are American) respond with more cultural worldview defense to death thoughts (r = .37) than do non‐college students (r = .24; Burke et al., n.d.).

[/quote]

Regarding differences between contemporary Americans and previous generations

[quote author=Weirdest People in the World]

Contemporary Americans may also be psychologically unusual compared to their forebears 50 or 100 years ago. Some documented changes among Americans over the past few decades include increasing individualism, as indicated by an increasingly solitary lifestyle dominated by individual‐centered activities and a decrease in group‐participation (Putnam 2000), and a lower need for social approval (Twenge & Im 2007). Again, these findings suggest that the unusual nature of Americans in these domains, as we reviewed earlier, may be a relatively recent phenomenon. These findings raise doubts as to whether research on contemporary American students (and WEIRD people more generally) is even extendable to American students of previous decades.

The evidence of temporal change is probably best for IQ . Research by Flynn (1987, 2007) shows that IQ scores increased over the last half century by 18 points in all industrialized nations for which there were adequate data. Moreover, this rise was driven primarily by increasing scores on the analytic subtests. This is a striking finding considering recent work showing how unusual Westerners are in their analytic reasoning styles. Given such findings, it seems plausible that Americans of only 50 or 100 years ago were reasoning in ways much more similar to the rest of the non‐Western world than Americans of today.

[/quote]

One of the key take-away points from the paper is that one needs to be careful in interpreting results coming from social and behavioral psychology studies which mostly tend to utilize western college undergrad populations. The authors recommend

[quote author=Weirdest People in the World]

Journal editors and reviewers should press authors to both explicitly discuss and defend the generalizability of their findings. Claims and confidence regarding generalizability must scale with the strength of the empirical defense. If a result is novel, being explicitly uncertain about generalizability should be fine, but one should not imply universality without an empirically‐grounded argument.

[/quote]