Palinurus

The Living Force

Source (Dutch only): De foto’s van SS’er Johann Niemann zijn macabere illustraties bij de verhalen van Sobibor

Added info from the newspaper:

Bildungswerk Stanislaw Hantz: Fotos aus Sobibor. Metropol Verlag; € 29. The English translation will be published in June.

The Niemann collection was donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. De Volkskrant received permission from the USHMM to print a limited number of photographs.

This piece was produced with the support of the Fonds Bijzondere Journalistieke Projecten.

Related coverage:

‘Welke woorden gebruik je voor iemand die medeverantwoordelijk is voor 28 duizend doden?’

Germany arrests 3 Auschwitz guard suspects, aged 88, 92 and 94 -- Sott.net

Poland seeks to rewrite WWII history, excludes Russia from participating in war memorial -- Sott.net

How the brutalized become brutal: Years of random violence, brutal repression and collective humiliation -- Sott.net

DeepL Translator said:Sobibor in pictures - Photos of Johan Niemann

The photographs of SS man Johann Niemann are macabre illustrations to the stories of Sobibor

'The camp looked like an ordinary farm, except for the barbed wire that surrounded the barracks, in the middle of a beautiful green forest', said Dov Freiberg, a Polish Jew who arrived in Sobibor on the first transport in 1942. Image United States Holocaust Museum

After more than seventy years the photo books of SS man Johann Niemann, Sobibor's 'extermination expert', have surfaced. His photographs are macabre illustrations to the stories of the survivors.

Rosanne Kropman - 31 January 2020, 17:02

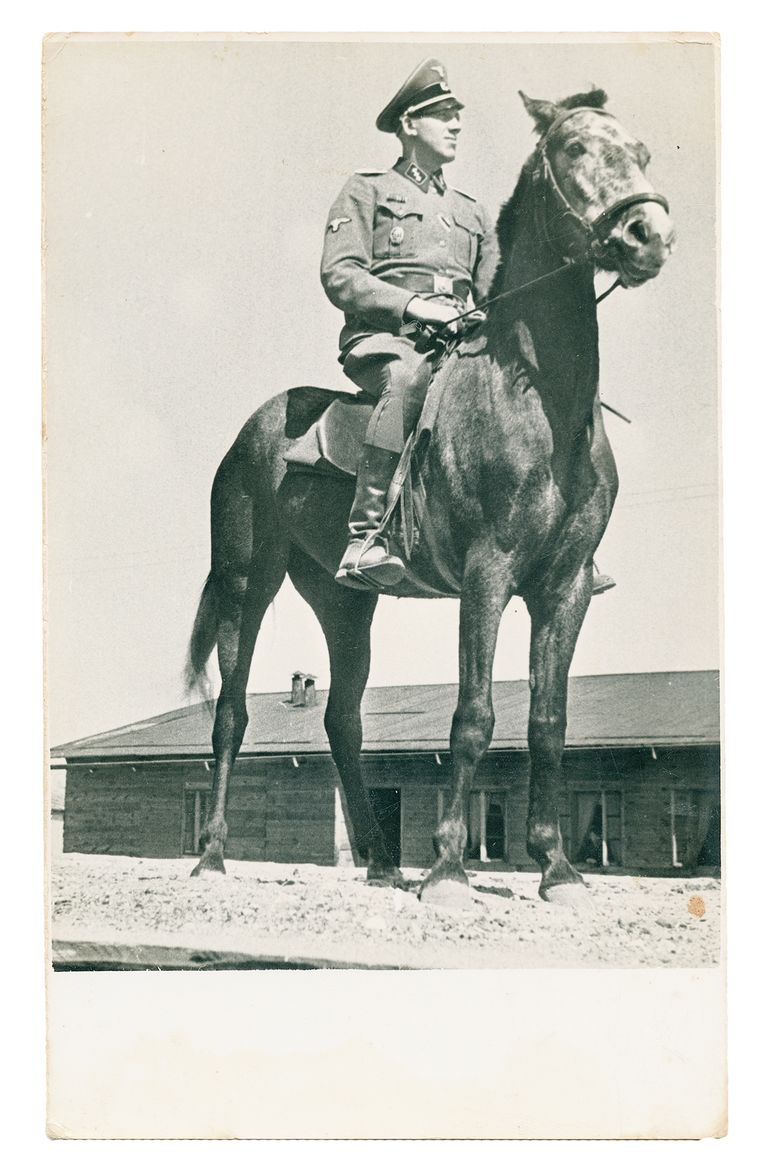

On the back of a large muscular horse, Johann Niemann stares into the distance from the platform of Sobibor extermination camp. He is standing on the spot where 170 thousand people were chased out of cattle wagons over a year and a half, only to be gassed and burned a few hours later. Niemann was photographed from below, just as Hitler was photographed so often. This way he seems taller, mightier. The photographer must have stood on the train track. On Niemann's collar are the SS Runes and his rank: Untersturmführer, or deputy commander.

The German hobby historian Hermann Adams found the photo in a cardboard box in the summer of 2019, during the last search of Niemann's grandson's house. For Adams the portrait is one of the most important pieces in his collection of documents about Niemann's SS career, which ended with the Sobibor uprising in 1943.

The portrait is larger than most of the other photos printed as postcards he found in the grandson's house. 'Cold sweat broke out on me when I saw that picture,' says Adams in his living room in the East Frisian town of Ihrhove, a village less than 10 kilometers from Völlen, the birthplace of Johann Niemann. 'Der König über allen, I thought.'

In 2013 Adams had tracked down the grandson after a long search, after he had been unsuccessful with other descendants of Niemann. Adams wanted to know if he still had pictures of his grandfather. The grandson had looked at him closely, but he didn't say no. 'Call me tonight.'

Not much later, the grandson, who doesn't want contact with the media, had shown one of his grandfather's two photo albums and held it with both hands and didn't want to let go. Adams was allowed to photograph two pages - and no more - if he promised not to show the images to anyone.

In 2015 Adams broke that promise. During a study trip to Sobibor extermination camp he showed the pictures to the tour guide of Bildungswerk Stanislaw Hantz, a German organization that wants to promote awareness about the Holocaust.

'We knew immediately that we had something special in our hands,' says Andreas Kahrs, a historian involved with the organization. Until then only two photographs of Sobibor were known. It was strictly forbidden for the camp staff to take photographs. 'There are many pieces from the legacies of victims, but photo books of an offender - that is unique.'

Back home, Adams went to the grandson to apologize for breaking his promise. But he had mainly come to ask him if there was more, and if he would consider handing over the photo books to Bildungswerk Stanislaw Hantz. 'Suppose something happens to you,' Adams said to him, 'then it ends up in the garbage can or at a flea market.' He convinced the grandson to turn his packed house inside out, looking for more material from his grandfather whom he had never known and whom, according to Adams, had never been talked about within the family.

From cardboard boxes, from cupboards and from the attic papers emerged, but especially photographs: 361, of which 62 were of Sobibor from the period 1942-1943. There were also four photographs of Belzec, an extermination camp where Niemann worked for three quarters of a year.

The discovery of the photos became world news last Tuesday: suddenly Sobibor was in the picture. Moreover, the German police had been able to identify war criminal Iwan Demjanjuk in two photographs of Sobibor. Demjanjuk was convicted at the end of his life for complicity in the murder of more than 28 thousand people. Until his death in 2012 he denied that he had been in Sobibor and died awaiting his appeal.

Together with Treblinka, Sobibor and Belzec were part of 'Aktion Reinhard', three extermination camps in a remote area in the East of occupied Poland. The three camps were set up for extermination and did not have a labor camp like Auschwitz. Those who arrived there by train had a virtually zero chance of survival. Most men, women and children were gassed the same day.

The small number of people who could recount the horrors is one of the reasons that these three places are relatively unknown. Belzec counted two survivors, on an estimated death toll of 430 thousand. In Sobibor 58 of the approximately 170 thousand prisoners reached the end of the war alive. 67 people survived Treblinka, on an estimated death toll of 925 thousand.

Another reason why few people know the history of these places is invisibility. As early as 1943 - still in the middle of the war - the three extermination camps were closed and razed to the ground. The forced laborers were murdered. The chance of discovery had become too great: the Russians were approaching and escapes had taken place both in Treblinka and Sobibor. Moreover, the Jews in eastern Poland had been virtually exterminated because of the effectiveness of these killing factories. In twenty months time, an estimated 1.5 million Jews had been murdered by some 120 Germans in the three camps of Aktion Reinhard.

More than 75 years after the liberation, Johann Niemann's photographs now colorize what the victims must have seen when they arrived in Sobibor, after having been packed for days in cattle wagons.

When Johann Niemann registered with Hitler's NSDAP in 1931, barely a month 18 years old, he trained as a house painter in the poverty-stricken hamlet of Völlen. His father went on horse-drawn carriage rides past farms to pick up full milk churns. The family was large, also for that period of time: nine children. Johann is the middle one, we read in the book Fotos aus Sobibor (Photos from Sobibor), published last Tuesday by Bildungswerk Stanislaw Hantz after four years of research.

In 1934 Niemann began to record his lightning career in National Socialism. That year he appeared as a guard in photographs taken in Esterwegen, a concentration camp for political prisoners near Völlen. Later he was transferred to Sachsenhausen, a concentration camp for political dissidents and Jews near Berlin. Until he was promoted to a secret post at the end of the 1930s. In 1939 he is asked for Aktion T4, the murder program for the sick and handicapped in various institutions in Germany. For Niemann the appointment is the prelude to his key role in the Holocaust.

Niemann becomes a 'burner' in Aktion T4: he removes the dead from the gas chamber and burns them in one of the specially built furnaces. The victims are killed upon arrival, after which the corpses are stripped of gold teeth and cremated.

There are no photographs in this case. During the eighteen months he works in the murder centers the viewer sees Niemann often posing outside in civilian clothes, as if on holiday in the countryside. In Grafeneck Castle, one of the murder centers in southern Germany, Niemann met many of his later colleagues in Sobibor. Siegfried Graetschus, the man who was murdered five minutes earlier than Niemann in the same barracks during the Sobibor uprising, is already in these pictures.

At the end of 1941 Niemann, together with five others, was sent to Belzec in Eastern Poland with the assignment to build a center for the extermination of Polish Jews. How they should do this, the Nazi leaders in Berlin left in the middle. The men quartered with Polish families and went to work as they had learned during the period of the patients murders in Germany, but on a much larger scale. The six men experiment with methods of gasification by carbon monoxide, first from gas cylinders, later by running a tank engine.

'We think that at first they had no idea what kind of destruction they were capable of. Once they were fully engaged, nothing stopped them,' says Andreas Kahrs, historian at Bildungswerk Stanislaw Hantz. 'Niemann was involved in the murder of about fifty people a day in Aktion T4. In Belzec and later Sobibor there were five thousand men, women and children on some days.'

That Niemann was involved from the outset in the development of Aktion Reinhard's extremely effective killing method was as yet unknown, says Kahrs. 'We knew his name and that he had been in Sobibor, but we had no idea of the central role he had played there. The photos of his various stations in Aktion T4, Belzec, and ultimately Sobibor show that he was a protagonist, an annihilation expert.'

Niemann's considerations or thoughts in his actions are unknown. No diary or other ego document has been found. 'The photographs show the perspective of a perpetrator, the image Niemann wanted to show at home', says Kahrs. One of the captions in the Sobibor album reads 'Memories'. He did not focus on the destruction, the atrocities or excesses in the camps, but on his own career.

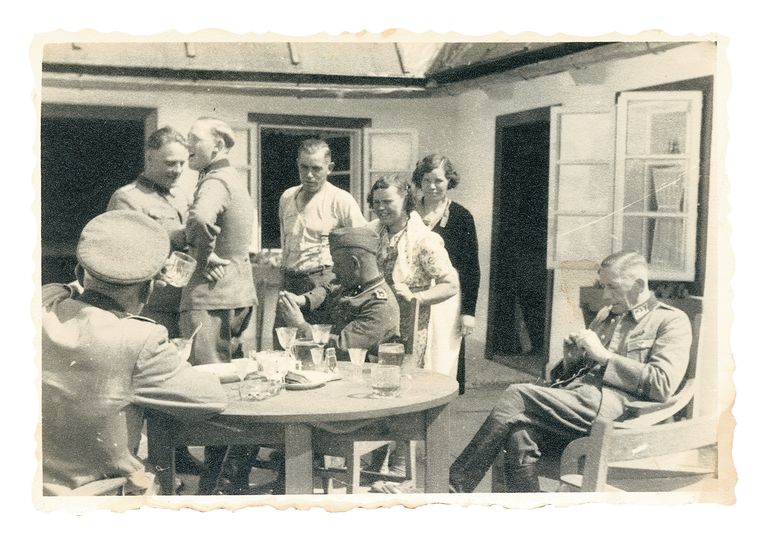

Part of the camp staff, sipping drinks in front of the canteen in the Vorlager, with presumably robbed crystal

glasses. A stone's throw away were the gas chambers. Johann Niemann is the third from the left.

Image United States Holocaust Museum

Niemann's photographs show whitewashed houses with neat curtains in front of the windows and raked front gardens fenced off with a small decorative fence of birch wood. We see Nazis toasting on the terrace of the canteen in the middle of Sobibor, probably with robbed crystal glasses. We see them laughing with an accordion and with the animals of the camp - a few hundred meters away from the gas chambers. Niemann often stands in the middle, in uniform. The more important his role in the Holocaust becomes, the more prominent he appears in his own photographs, it seems.

Occasionally there are forced laborers in the photographs, quasi as extras in the background. Not in the striped suits we know from Auschwitz, but in civilian clothes. We never see the 'Himmelfahrtstrasse', the passage the Jews had to go through to the eight gas chambers, nor the mass graves or the burning of corpses in Camp III. The photographer - or photographers, it is unknown who made the images - remains as much as possible within the framework of the play that the Nazis wanted to stage to disguise the destruction.

In the Vorlager, where most of the photographs of Sobibor were taken, live the SS and the Trawniki, guards of Central or Eastern European origin. Next to their sleeping quarters there is a canteen with a terrace, a bowling alley, a kitchen and a laundry. There was even a dentist, a Jewish forced laborer who had to maintain the teeth of the staff, we read in Fotos aus Sobibor.

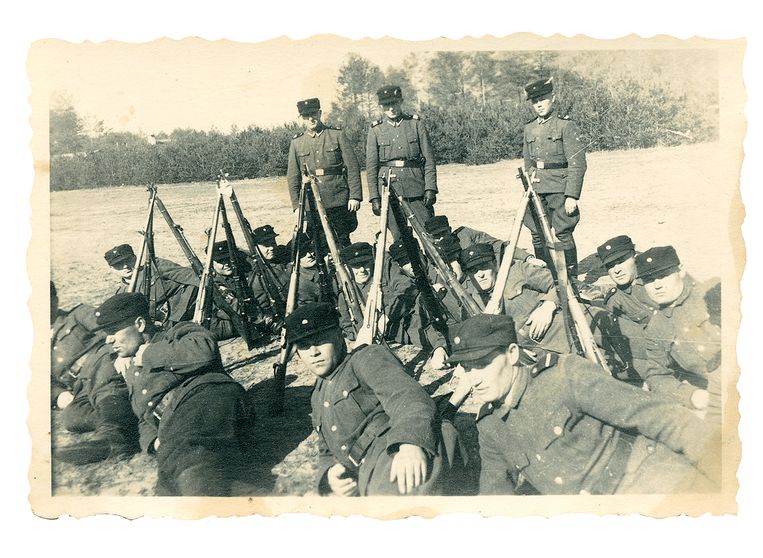

This photo of camp guards shows the barbershop on the top left, where Jewish women were being haircut

before they were gassed. Image United States Holocaust Museum

For the prisoners the first impression of Sobibor was confusing. Jules Schelvis, who spent a few hours in the camp before he was taken away to a labor camp and lost his wife and other family, wrote in his book about Sobibor: 'The barracks looked like cottages from Tirol and had names like Lustiger Floh, Gottes Heimat, and Schwalbennest'. Selma Engel, one of the two Dutch survivors of the Sobibor uprising in October 1943, says in the biography Selma van Ad van Liempt: 'When we arrived in the camp it seemed ideal. There were curtains with flowers hanging in front of the windows'. And Eda Lichtman, a Polish survivor, wrote: 'Nobody wanted to believe that this was a place where people were destroyed.'

The photographs from Johann Niemann show in the same Vorlager a farmyard with a decorated well in the middle. On the wooden roof is a dovecote with a windmill as a wind-vane gear. Behind it are the stables, with two wooden horse's heads above them. There was no shortage of craftsmen in Sobibor; the woodcarving was probably done by prisoners.

'The camp looked like an ordinary farm, except for the barbed wire that surrounded the barracks, in the middle of a beautiful green forest', says Dov Freiberg, a Polish Jew who arrived in Sobibor on the first transport in 1942, in a testimony in the archives of Yad Vashem.

Anyone who looks at the photos as a layperson will probably see the same thing. Only when you know what you are looking at and what you have to pay attention to, you see details of the atrocities that took place behind the facade. In the background of one of the two group photos of the Trawniki, which also features Demjanjuk, a white structure protrudes above the tree. Stanislaw Hantz observed that it was the chimney of the gas chambers. It also shows the roof of the hairdresser's barrack where the women's hair was cut off before they were gassed. The grab with which the corpses were removed from the mass graves for incineration - to prevent discovery - towers over the horizon on several photographs. And many photos show the barbed wire with which the Vorlager was separated from the murder factory.

To complete the facade, animals were kept in Sobibor. Niemann is pictured laughing with two other guards, each with a newborn pig in his hand. Another photo shows two guards with a dog, with a flock of large white geese in the background. Both the geese and the dogs come back in testimonies of survivors. In the documentary Shoah Sobibor survivor Jehuda Lerner says: 'We heard screaming and yelling. It was the sound of real geese. It lasted for an hour, then suddenly it became silent again. Later we heard that the Germans kept hundreds of geese. The moment the Jews started screaming, the Germans panicked the geese. The geese drowned the people's voices. They were real geese, bred especially to smother people's screams.'

Johann Niemann Image United States Holocaust Museum

The dogs were used to hunt down prisoners and instill fear. Survivor Eda Lichtman talks in her statement at the Sobibor trial about a Saint Bernard dog called Barry: two SS men 'took Barry with them. The dog quietly walked next to them, but when his boss asked one of the prisoners 'so you don't want to work,' Barry flew up to that person, biting and pulling, tearing off pieces of meat.'

The horrors in Sobibor came to an end in October 1943 when hundreds of prisoners escaped during the most successful revolt of the Holocaust, after which the Nazis razed the camp to the ground.

Niemann was the second SS man to be killed during the uprising. After prisoner Jehuda Lerner and a comrade first lured SS man Siegfried Graetschus to the tailor's barracks supposedly to have him try on a robbed coat and then cleaved his skull with an ax, Niemann falls into the same trap a few minutes later.

The gateway to Sobibor in the spring of 1943. Approximately 170 thousand Jews entered the extermination

camp on foot or by truck, 58 of them survived. Image United States Holocaust Museum

In Shoah, Jehuda Lerner talks about it: 'He (Niemann, ed.) looked around, said that he thought the workplace was dirty, that we should whiten the walls and clean up the mess. He stepped forward, looked around. Graetschus' arm stuck out under the pile of coats, which we had apparently overlooked. The German took a few steps and stood on his hand. So he started shouting: 'Was ist das'?! My comrade immediately jumped forward and punched him. The German collapsed and then I gave him a second whack. I'll never forget that. The blade of the ax came on his teeth and that gave a kind of spark.'

Five days after the uprising Johann Niemann and ten other killed SS men were buried with a lot of Nazi ceremonial in the town of Chelm, not far from Sobibor. There are pictures of this as well. Drummed up soldiers with a stern gaze brought the Hitler salute to the coffins covered with swastika flags. One coffin stands prominent in the middle: that of Johann Niemann.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Added info from the newspaper:

Bildungswerk Stanislaw Hantz: Fotos aus Sobibor. Metropol Verlag; € 29. The English translation will be published in June.

The Niemann collection was donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. De Volkskrant received permission from the USHMM to print a limited number of photographs.

This piece was produced with the support of the Fonds Bijzondere Journalistieke Projecten.

Related coverage:

‘Welke woorden gebruik je voor iemand die medeverantwoordelijk is voor 28 duizend doden?’

Germany arrests 3 Auschwitz guard suspects, aged 88, 92 and 94 -- Sott.net

Poland seeks to rewrite WWII history, excludes Russia from participating in war memorial -- Sott.net

How the brutalized become brutal: Years of random violence, brutal repression and collective humiliation -- Sott.net