Opulent 1,500-year-old church to mystery ‘glorious martyr’ found at Beit Shemesh

Site yields rare intact crypt of anonymous martyr immortalized by Greek inscription; Jerusalem museum exhibit of findings showcases massive collection of delicate glass artifacts

Opulent 1,500-year-old church to mystery ‘glorious martyr’ found at Beit Shemesh

By

Amanda Borschel-Dan 23 October 2019, 11:41 am

1

-

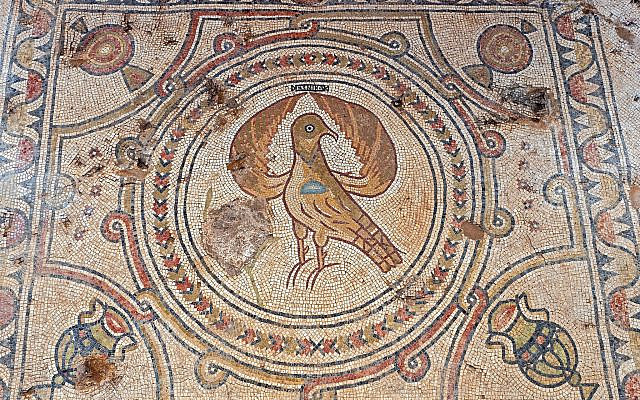

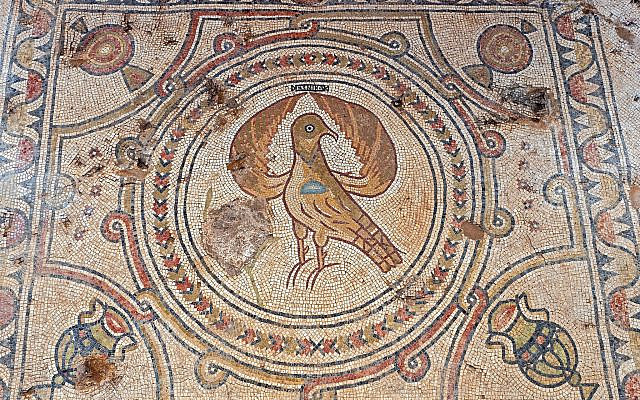

The Eagle, symbol of the Byzantine Empire, discovered at a Byzantine-era church complex in Ramat Beit Shemesh, October 2019. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Director of Excavation, Benjamin Storchan, at the crypt’s entrance at the Ramat Shemesh Byzantine-era church. (Yoli Schwartz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

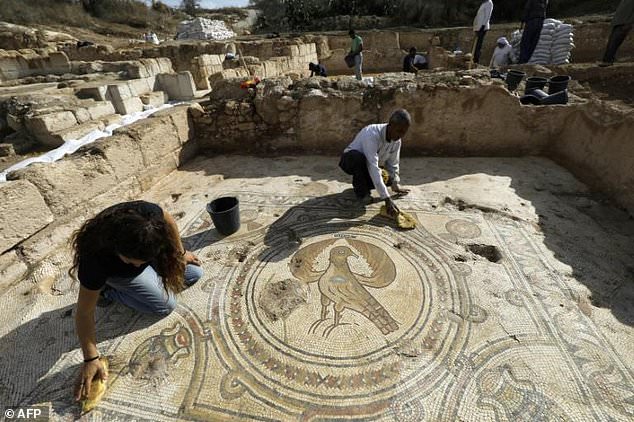

Thousands of youth participated in the excavation in Ramat Beit Shemesh over the past three years. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Unique cross-shaped baptismal font in the Byzantine-era church in Ramat Beit Shemesh. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

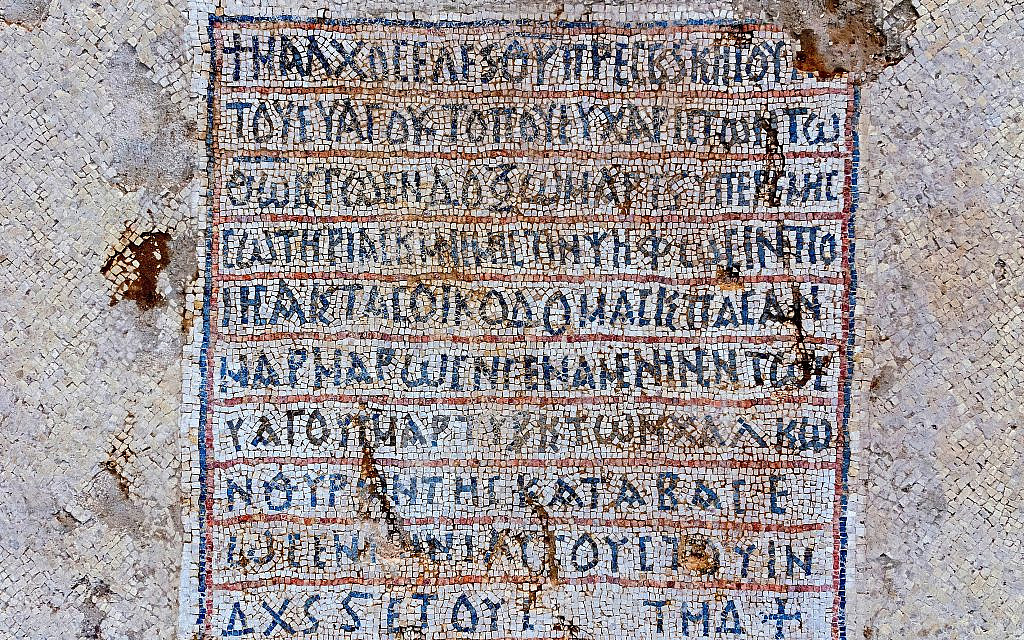

Greek inscription in the floor of the Byzantine-era church in Ramat Beit Shemesh, October 2019. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Mosaics exposed from the floor of the Byzantine-era church in Ramat Beit Shemesh, October 2019. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Site of the church exposed in Ramat Beit Shemesh, October 2019. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

Fifteen hundred years ago, Christian pilgrims flocked to an opulent basilica church near Beit Shemesh built with donations from the Byzantine emperor himself in honor of a mysterious “glorious martyr,” the Israel Antiquities Authority said Wednesday.

“The martyr’s identity is not known, but the exceptional opulence of the structure and its inscriptions indicate that this person was an important figure,” said excavation director Benjamin Storchan in the IAA press release.

The church compound, 1.5 dunam or just over a third of an acre in size, has a rare intact underground crypt that once presumably contained the relics of the anonymous martyr immortalized in a Greek inscription at the site.

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

The crypt was such a tourist draw that it was, unusually, reached by two impressive staircases.

The Eagle, symbol of the Byzantine Empire, discovered at a Byzantine-era church complex in Ramat Beit Shemesh, October 2019. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

A stone quatrefoil (four-leaved) crucifix baptismal font was discovered at the site. It is a design that is less common to Byzantine-era Holy Land sites but is found throughout the empire, including in North Africa. Among the colorfully intricate fruit, flora and fauna mosaic designs is the imperial eagle, which alongside an inscription detailing the donation of Emperor Tiberius II Constantine (574-582 CE), ties the site to the sprawling Byzantine empire.

“Imperial involvement in the building’s expansion is evoked by the image of a large eagle with outspread wings – the symbol of the Byzantine Empire – which appears in one of the mosaics,” said Storchan.

The three-year salvage excavation of the glorious martyr site was conducted by the IAA and a corps of some 5,000 youth volunteers ahead of the construction of a new neighborhood in Ramat Beit Shemesh.

Two staircases that led pilgrims to and from the crypt at the Byzantine-era church in Ramat Beit Shemesh. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

The circa NIS 7 million ($2 million) project of excavation and documentation is financed by the Construction and Housing Ministry and the CPM Corporation and has spurred an exhibit at Jerusalem’s Bible Lands Museum, which is opening Wednesday night.

Among the artifacts on display are examples of numerous delicate glass objects. The press release calls the assembly “the most complete collection of Byzantine glass windows and lamps ever found at a single site in Israel.” Additionally, the Bible Lands Museum will present some of the 300 intact Abassid-period clay lamps discovered at the site.

Mosaics exposed from the floor of the Byzantine-era church in Ramat Beit Shemesh, October 2019. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

Ahead of the exhibit opening Wednesday, Bible Lands Museum director general Amanda Weiss said in a statement, “We are proud of our collaboration with the Israel Antiquities Authority bringing to light these important new finds for the thousands of visitors from all faiths ages and nationalities, inviting them to appreciate the rich cultural heritage of the Land of Israel.”

The church was initially erected circa 543 CE under the reign of Emperor Justinian in the 6th century CE (527-565). A chapel was added under Emperor Tiberius II Constantine.

Thousands of youth participated in the excavation in Ramat Beit Shemesh over the past three years. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

According to the IAA release, the church’s walls were painted with colorful frescoes and it was decorated with “lofty pillars crowned with impressive capitals.” The basilica was a long building with three sections that were divided by two rows of columns. It included a central nave flanked by two halls, according to the press release, and an atrium greeted pilgrims at the church’s entrance. The inscription to the “glorious martyr” is found in this courtyard.

But it is its subterranean layer that is of most interest to tourists, past and present: Few of the excavated churches in Israel have preserved, fully intact crypts, said Storchan.

Director of Excavation, Benjamin Storchan, at the crypt’s entrance at the Ramat Shemesh Byzantine-era church. (Yoli Schwartz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

“The crypt served as an underground burial chamber that apparently housed the remains (relics) of the martyr. The crypt was accessed via parallel staircases – one leading down into the chamber, the other leading back up into the prayer hall. This enabled large groups of Christian pilgrims to visit the place,” said Storchan.

According to Storchan, a Greek inscription details that Emperor Tiberius II Constantine supported the expansion of the glorious martyr’s church.

Greek inscription in the floor of the Byzantine-era church in Ramat Beit Shemesh, October 2019. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

“Numerous written sources attest to imperial funding for churches in Israel; however, little is known from archaeological evidence such as dedicatory inscriptions like the one found in Beit Shemesh,” said Storchan.

Mosaics exposed from the floor of the Byzantine-era church in Ramat Beit Shemesh, October 2019. (Asaf Peretz, Israel Antiquities Authority)

www.israelnationalnews.com

www.israelnationalnews.com