Interesting findings in this paper.

www.psychologytoday.com

www.psychologytoday.com

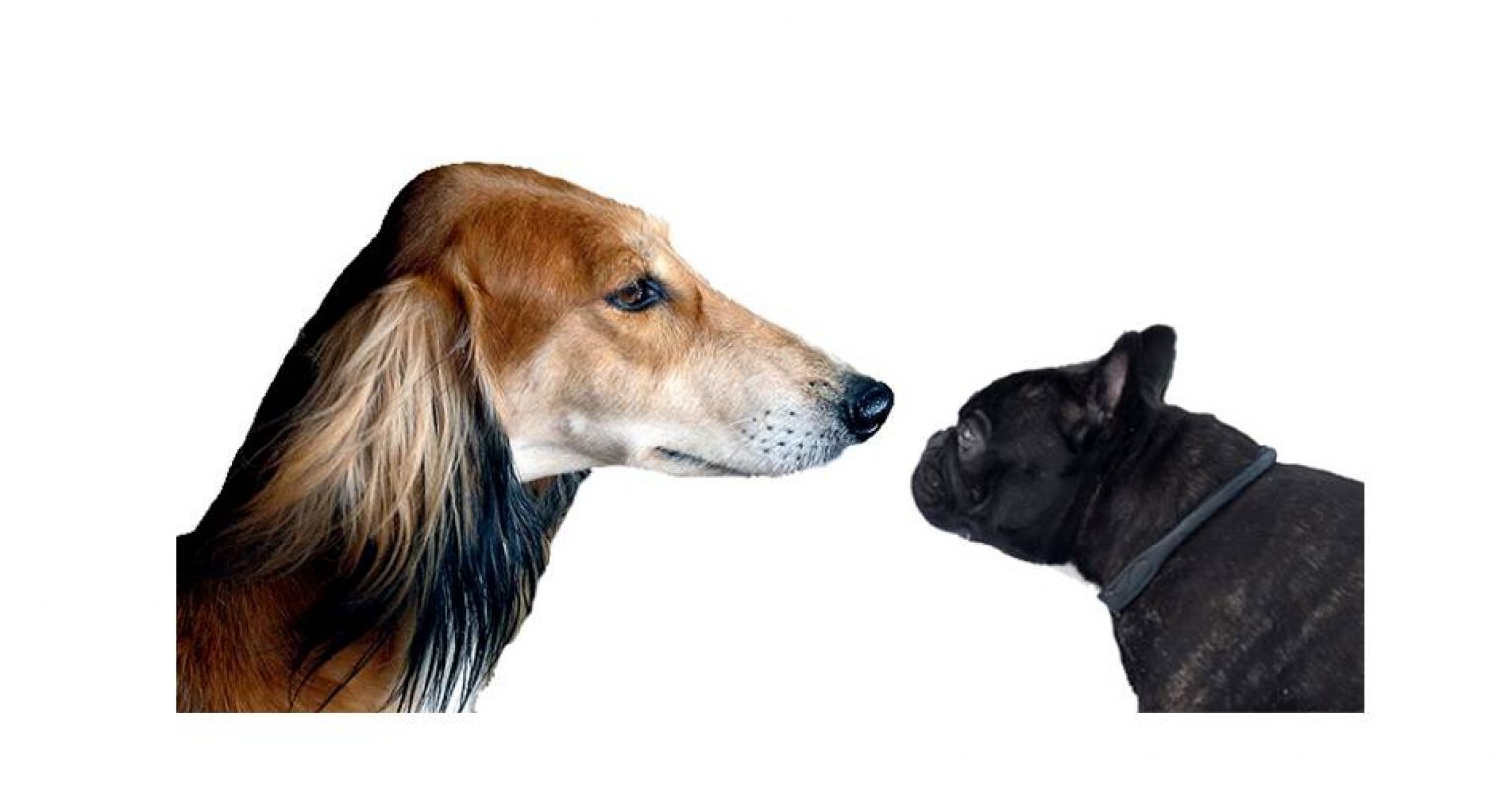

A Dog's Size and Head Shape Predicts Its Behavior

New data suggests that the behavioral tendencies of dogs can be predicted by their height, weight, and whether they have long or short skulls.

The dog's height predicted a number of aspects of the dog's behavioral tendencies. It may be a surprise to many people to find that shorter dogs were found to be generally more aggressive than taller dogs. In addition the taller dogs tended to show more affection, cooperation, and playfulness with humans.

The dog's weight also predicted certain personality characteristics. Heavier dogs tended to be bolder, more inquisitive, and attentive. Lighter dogs tended to be more cautious and fearful.

Head shape also predicted some differences in temperament. The brachycephalic dogs seem to be more engaged with their owners with a higher interest in human-directed play. On the other hand these short-faced dogs were more defensive when faced with a difficult to interpret situation (such as seeing a person dressed like a ghost). The dolichocephalic dogs seem to be less likely to engage in object play, especially with unfamiliar humans. However these long-faced dogs were not as easily startled and recovered more quickly when an unexpected event occurred.

These are just the major findings. However the overall conclusion is that the height, weight, and head shape of dogs can predict certain important behavioral and temperament variables including certain aspects of aggression, fearfulness, sociability and affection. In general it supports Sigmund Freud's contention that "Physiology is destiny," at least when it comes to the size and shape of dogs.