I'm halfway through this book and it's really fascinating. The authors try to explain who were Denisovans, their connection to Göbekli Tepe and other neolithic sites. Collins' explanation of the symbology behind the Vulture Stone and Lascaux painting is quite fascinating and in my opinion not less plausible than the Sweatman's one (Collins actually takes into account more elements of the shaft scene of Lascaux and of the Vulture Stone than Sweatman does). Here are some quotes from the book.

Comet shamans

CALMING CATASTROPHOBIA

Flight of the Vulture

Cult of the Skull

COMPLEX HUNTER-GATHERERS

Journeys of the Soul

THE SOLUTREAN CONNECTION

Shaft of the Dead Man

To be continued.

We must therefore ask ourselves what kind of effect the Younger Dryas comet impact, with its accompanying mini–ice age, might have had on the emergence of Göbekli Tepe in particular. How did it affect what was built? And what kinds of people did it bring into southeastern Anatolia, escaping the aftermath of the Younger Dryas event elsewhere in the ancient world? As will become clear, something extraordinary was taking place in southeastern Anatolia around the time of the foundation of Göbekli Tepe—a series of events that would go on to catalyze not only what we call the Neolithic revolution but also the rise of Western civilization. More importantly, we will see that what occurred in Anatolia at this time was not only the start of something new but also the culmination of a dissemination of ancient technologies and cosmological ideas that had begun with the emergence of the first human societies at the commencement of the Upper Paleolithic age some 45,000 years ago. More importantly, there is now compelling evidence that the rise of our own civilization, not only on the Eurasian continent but also in North America and South America, was the result of contact with an extinct human species known today as the Denisovans. It is their impact on the world that this book...

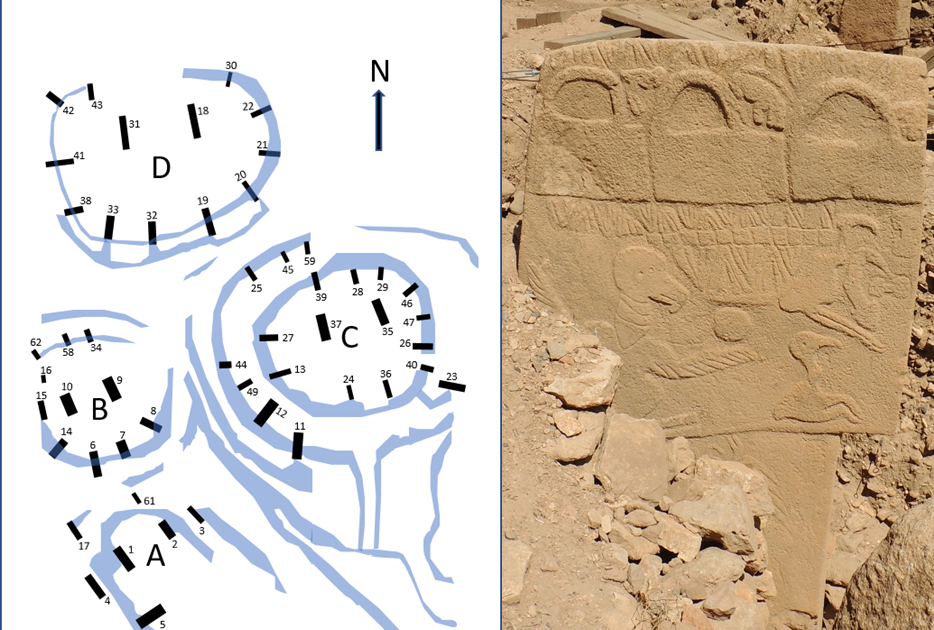

As I exclusively proposed in 2014, the earliest stone installations at Göbekli Tepe were most likely built as liminal interfaces, forming a link between this world and the next, so that shamans might easily deal with perceived threats from supernatural intruders appearing in our skies in the form of comets. Indeed, there is every reason to believe that it was for this express purpose that monumental architecture started to appear in different parts of the world at this time, Göbekli Tepe and Jericho being prime examples of this sudden emergence of sophisticated architectural design. To back up this theory, I have drawn attention to the presence at Göbekli Tepe of comet-related imagery, especially in the site’s oldest and most accomplished installation, Enclosure D. This was built circa 9600 BCE, a date corresponding very well to the abrupt end of the 1,200-year mini–ice age triggered by the Younger Dryas impact event.

Comet shamans

On Pillar 18’s front narrow edge is the belt’s central feature. This takes the form of a curious symbol consisting of a filled circle from which three parallel spokes jut upward (see plate 5 ). When I first saw this glyph, I was struck by its similarity to a three-tailed comet, which I believe it to be (see fig. 1.1). The likeness is uncanny, and the fact that the glyph features so prominently on the belt tells us that this is to be seen as a symbol associated with the function of the wearer. The pillar, I suspect, represents an ancestral shaman, one considered to have had mastery over the supernatural forces seen as responsible for catastrophes. Further linking the figure with comets is the fact that beneath the belts of both Pillar 18 and its western counterpart, Pillar 31, is the carved relief of a long-tailed animal pelt, almost certainly that of a fox. The use here of fox pelts is significant as the animal is a well-known symbol of comets, its bushy tail symbolizing the comet’s own tail...

CALMING CATASTROPHOBIA

It is the suspicion of the present author that the shamanic society responsible for Göbekli Tepe had also worked out that Halley’s Comet returned every seventy-six years. This was powerful knowledge which could then be used to convince the local population of hunter-gatherers that their shamans had predictive knowledge of the appearance of comets. In this way, they had the ability to counteract the comets’ baleful influence, and in doing so prevent the potential destruction of the world. If correct, then this was how these elite groups of individuals managed to calm the catastrophobia that had been present among the local populace since the terrifying events of the Younger Dryas comet impact.

Flight of the Vulture

In 2017, Pillar 43 came to the attention of the world’s media following claims in a peer-reviewed paper that its relief imagery is a detailed snapshot of the night sky on the day in “10,950 BCE” (+/–250 years) that the Younger Dryas comet decimated the northern hemisphere. The authors of the study acknowledge that the assumed connection between Göbekli Tepe and the comet impact was originally proposed by myself in Göbekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods in 2014, their own theories having been inspired by these earlier deductions. [refers to Sweatman] Although these claims are now finding favor among some science journalists, they have received a rather colder reception from the archaeological team responsible for excavations at Göbekli Tepe. In their opinion, Pillar 43 was not carved during this much earlier epoch, and, what’s more, such ideas make little sense of Göbekli Tepe’s time frame, as they contend it emerged no earlier than the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period, circa 9600 to 8800 BCE.

Points of coordination

Aside from the vulture, scorpion, and several more stranger creatures seen on Pillar 43, two other key features of its carved relief can provide fixed points of coordination between the skies of 9600 BCE and the positioning of any astronomical figures represented as carved relief. These are the horizontal dividing line between the T-shaped head and the stem of the pillar and the filled circle or ball-like object seen above the vulture’s left wing (to your right when facing toward it). Those who identify the vulture as Sagittarius see this circle as a representation of the sun passing through the zodiacal constellation in question. Yet if the Göbekli builders had wanted to depict the sun, then it is likely they would have ensured there was no ambiguity as to what the observer was seeing when examining the pillar’s relief imagery, especially since we know that in the rock art of southeastern Anatolia filled circles were used to represent the human soul in its form as an abstract human head or skull (see chapter 3).

A more plausible explanation was surely needed, one that better made sense of the ball’s possible role as the disembodied head and soul of the headless male individual, complete with an erect penis, displayed toward the base of the pillar. He is shown on the neck of another vulture, of which only the upper body is visible above ground level. Since the central vulture’s stylized, W-shaped wings appear to tilt toward the ball positioned over its left wing, it implies that the latter, if signifying a celestial object, was located in the same area of sky. So if all these disparate elements—the pillar’s main vulture, its scorpion, the horizontal dividing line between the head and stem, and the ball above the wing of the bird—all formed part of the same astronomical picture, could they be matched with key components of the night sky for 9600 BCE?

Hale’s Findings

Consulting a suitable sky program, British chartered engineer Rodney Hale, who has worked in the field of archaeoastronomy for over twenty years, has devised a satisfactory answer to this puzzling enigma. If the dividing line between the two sections of the pillar is taken to be the local horizon and the constellation of Scorpius is lined up with the approximate position of the stone’s scorpion, then the ball placed above the wing of the vulture corresponds perfectly with the northern celestial pole, the turning point of the heavens around which the stars are seen to revolve each night (see fig. 2.2). During the epoch of 9600 BCE, the northern celestial pole was located in the constellation of Hercules. Yet at the time no bright star was close enough for it to assume the role of polestar. Since then, the pole has shifted its position due to the consequences of precession, caused by the axial wobble of the Earth across a cycle of approximately 26,000 years. Today, the northern celestial pole is in the constellation of Ursa Minor, the Little Bear, and is marked by the star Polaris ( α Ursae Minoris), known also as the North Star.

Hole in the sky

Identifying the ball on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43 as the turning point of the northern night sky makes perfect sense of its role as the disembodied head and soul of the headless figure seen at the base of Pillar 43. Among the shamanic societies of northern Asia, such as the Chukchee and Altaians, the northern celestial pole acted as a hole through which the soul had to pass in order to reach the sky world. This “hole in the sky” was compared with the round smoke hole of a yurt or tent, through which the soul of the shaman, as well as that of any person who died inside the yurt, would navigate to reach the afterlife.

Identifying the Vulture

If the ball on Pillar 43 does represent the northern celestial pole, as Rodney Hale has determined, then with the very slightly askew dividing line between the stone’s head and the stem acting as the local horizon, and the scorpion representing as the constellation of Scorpius, its main central vulture corresponds with the region of sky occupied by the constellation of Cygnus, the celestial swan of Greek Hellenic star lore. Its stars match very well the vulture’s general appearance, angle, and overall proportions. This surmise seems particularly apparent in the case of the vulture’s W-shaped wings, which resemble those of Cygnus in its role as a celestial bird as it would have been seen when the pillar was carved around 9600 BCE. In addition to this, the eye of the vulture corresponds closely to the astronomical position of the constellation’s brightest star, Deneb (α Cygni).

Yet if the stone’s dividing line is matched with the local horizon and the ball synchronized with the northern celestial pole, the vulture becomes enormous, embracing the stars of various neighboring constellations, including Vulpecula, Sagitta, and Delphinus, as well as others in Pegasus, Hercules, and Lyra. What is more, the fact that the rear half of the vulture remains obscured by Enclosure D’s ringwall means that its back and spine would also have included stars from the constellation of Aquila, the eagle. Covering such an expanse of sky means that Pillar 43’s vulture synchronizes with the three bright stars forming what is known as the Summer Triangle. These are Deneb in Cygnus, Altair in Aquila, and Vega in Lyra. Interestingly, all three constellations were identified in Greek Hellenic tradition as vultures. Collectively, they are recalled in Greek Hellenic myth as the three monstrous creatures known as the Stymphalian birds or Harpies, described as part human, part vulture. In one myth, they are driven away by Hercules during his sixth labor.

In Babylonian mythology, Cygnus, Aquila, and Lyra were the three sky birds that attack the god Bel-Marduk, the Mesopotamian equivalent of Hercules. More significantly, in Armenian sky lore the stars of Cygnus were anciently seen as a constellation known as Angegh, the vulture. 21 In the knowledge that the former kingdom of Armenia Major embraced parts of southeastern Anatolia, including the Şanlıurfa province, this identification is of paramount importance to the matter at hand for it tells us that the vulture is simply an expanded form of the constellation of Cygnus, one embracing all three stars of the Summer Triangle...

From these realizations, we are left with the impression that the soul of the headless individual seen at the base of the pillar has departed its material existence and has now reached its destination, which appears to have been the northern celestial pole, the “hole in the sky” of shamanic tradition. The soul’s presence in the form of the ball-like device seems acknowledged, honored even, by the main vulture, which has its wings tilted slightly toward the ball...

That Scorpius is depicted below the horizon might well have something to do with the fact that the constellation has traditionally been seen as a Lower World creature, and even as a guardian of the entrance to the land of the dead. Thus, the scorpion on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43 reflects a similar theme. In other words, rites concerning the transition of the soul from the land of the living to the realm of the dead might well have been possible only after the Scorpius constellation had set below the horizon. Doing so at any other time might have meant unnecessary danger to the soul, a theme reflected in the fact that the scorpion is clearly a deadly creature, its sting sometimes fatal to its victim.

Cult of the Skull

In 2017, it was announced that excavators at Göbekli Tepe had unearthed fragments of three human skulls that had been deliberately modified for use in what can only be described as a cult of the skull, arguably one of its earliest manifestations anywhere in the world. One cranial fragment has a deep vertical groove from front to back. Another has a hole bored through it—one of two such holes—allowing the skull to be hung on a cord, while a third fragment has undeniable defleshing marks, suggesting that the scalp was removed postmortem. These and other indications of enhancement make it clear that the skulls were featured in ritualistic practices soon after the site’s foundation circa 9600 BCE...

Skulls are very often shown in association with vultures, which were primary symbols of death and rebirth in Anatolia and the Near East during the early Neolithic age. At the Neolithic urban center of Çatalhöyük in southern-central Anatolia, which thrived circa 7000 to 5500 BCE, painted frescoes depict vultures protecting abstract human heads shown as balls with eyes and mouth. Here too excavators have found human skulls set aside for use in ritualistic practices.

At Göbekli Tepe, rediscovered fragments of totem poles show vultures in association with human heads, while on a T-shaped pillar (Pillar 57) in the newly uncovered Enclosure H, a ball-like object that is almost certainly a skull is shown flanked by two snakes. In addition to this, a large fragment of stone displaying carved relief, found deliberately positioned on the north side of Enclosure D’s Pillar 18, its eastern-central monolith, shows a disembodied human head immediately above a vulture with open wings (see fig. 3.1). The existence of this carved fragment, which was probably in secondary use when placed in position, helps us to understand why the ball-like object above the wing of the central vulture on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43 should be identified as an abstract human head, and not as the sun passing through the constellation of Sagittarius.

CYGNUS ALIGNMENTS

Elsewhere, I present compelling evidence that Göbekli Tepe’s oldest and most accomplished installations—Enclosures B, C, D, and H—are aligned north-northwest toward the setting of the Cygnus star Deneb, 4 a theory independently confirmed in a study of the site’s astronomical alignments by Italian academics Alessandro de Lorenzis and Vincenzo Orofino of the University of Salento. 5 These alignments toward Cygnus are further confirmed by the positioning of porthole stones in the north-northwest sections of the ringwalls of Enclosures C, D, and H. Each one is aligned so that the setting of Deneb on the local horizon would have been visible through its aperture as viewed from between the installation’s twin central pillars, thus providing a direct link between the stars of Cygnus and the spirit of the shaman or deceased person...

That the porthole stones in the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe were aligned north-northwest toward Cygnus, and not due north toward the northern celestial pole in its role as the “hole in the sky,” implies that upon exiting the enclosure the soul was expected to travel first to the realm of Cygnus, the celestial vulture, before continuing its journey to the afterlife. Why might this have been?

THE DARK RIFT

The answer is that Cygnus is positioned very prominently within the Milky Way, the starry stream forming the outer edge of our disk-like galaxy. This pathway of stars was anciently seen as a road or river that permitted the soul access to the sky world. Cygnus itself is located exactly where the Milky Way bifurcates into two separate branches due to the presence of dust and debris directly in line with the galactic plane. Known as the Dark Rift, Great Rift, or Cygnus Rift, this dark band, which begins in the vicinity of the star Deneb, continues all the way down to the vicinity of the stars of Sagittarius. Here one arm expands to form a bridge with the southern extension of the Milky Way while the other ends immediately above the stars of the Scorpius constellation.(Birds such as swans, geese, eagles, and vultures are primary symbols of the soul’s journey to and from the afterlife.) It is likely therefore that the Pre-Pottery Neolithic peoples of Anatolia and the Near East viewed the Dark Rift in a similar manner, seeing it as a darkened road to the sky world. The fact that the Dark Rift can be seen to begin, or alternately, end, immediately above the stars of Scorpius is telling indeed, especially since it is the scorpion that appears immediately beneath the horizon on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43.

Very likely the Scorpius constellation was seen as a threat to the soul on its journey to the afterlife, especially as it sought to join the Milky Way. It is in this same vicinity that the sun crosses the starry stream in only one of two places in the sky, the other being in the vicinity of the constellations of Taurus, Gemini, and Orion on the opposite side of the sky. The importance of this synchronization between the sun and the Milky Way meant that at certain times of the year, most obviously at the summer or winter solstice, the Milky Way would have been seen to rise up into the sky from the same position where the sun had either just set or was about to rise. This is something that would have been interpreted as a moment when the souls of either the departed or those of shamans were able to make the transition from the physical environment to the place of the afterlife.

SKY BURIALS

The use of vultures as primary symbols of death and rebirth during the PrePottery Neolithic age, circa 9600 to 6000 BCE, probably came about because human carcasses were often left out on wooden platforms for vultures to swoop down and pick clean the meat and bones, a practice known today as sky burial. This defleshing process, called excarnation, would have included the removal of the head postmortem. Since the head was seen as the seat of the soul, this permitted the vulture to become a primary symbol of the soul’s journey to the afterlife. It is for this reason that the vulture appears in association with heads in relief art and as life-like carvings at sites like Göbekli Tepe, Nevalı Çori, and Çatalhöyük.

Yet it is important also to remember that this apparently hazardous journey did not just involve the souls of the dead. It included those of shamans as well. They would have entered the sky world during dream incubation (the cultivation of meaningful dreams through ritual processes), and altered states of consciousness to deal with supernatural creatures seen as a threat to the stability of the world. For this they would have undergone some kind of symbolic death to enter or be “reborn” into the next world. Very often, the achievement of an altered state of consciousness involved the ingestion of dangerous hallucinogens, which would have brought the shaman very near to death. Once, however, a sense of connection with the otherworld was established, the shaman would have been able to conduct spirit communications with the supernatural inhabitants of these normally invisible realms until the effects ceased and their soul “returned” to its physical body. Thus, the headless individuals seen on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43 and within painted frescoes at Çatalhöyük do not necessarily have to signify a dead person. More likely, they represent the physical body of a shaman who is working with the spirit of the vulture in its role as a psychopomp to gain entrance to the sky world.

FLIGHT OF THE SHAMAN

What all this tells us is that the cosmological structure behind the beliefs and practices of those who built Göbekli Tepe, circa 9600 BCE, possessed striking parallels with the shamanistic traditions of tribal cultures as far away as northern Eurasia, Siberia, and Mongolia in particular...

The importance of shamanism at Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites like Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Anatolia, however, is that it was formalized out of necessity so that the baleful influence of comets could be quickly neutralized. Doing so would allay the catastrophobia of the local population, at least until the next major comet appeared in the skies...

WORSHIP OF THE SUN

The world was now a different place, and with the coming of the Neolithic revolution and the fear of further cataclysms gradually receding, the function of cult centers like Göbekli Tepe started to change. No longer were they oriented toward the stars of Cygnus and the Milky Way. Instead, the enclosures, which started to become much simpler in design, were turned toward the rising sun at the time of either the equinoxes or solstices. The reason for this change in direction was because the most important consideration now was whether the sun would continue to ripen the wheat and barley so that communities could produce everything from bread to cake to beer. (The oldest stone beer vats anywhere in the world were found in some of the younger enclosures at Göbekli Tepe.) The duties of the shamanic priesthood had now become even more formalized, revolving around the death and rebirth of the sun across its yearly cycle...

THE END OF GÖBEKLI TEPE

...Yet questions remain: Who were the first shamans of Göbekli Tepe? Why were they seen as having mastery over comets and cosmic catastrophes, and where exactly did they come from? As we will see next, there is every reason to suspect that the builders of Göbekli Tepe came not from the south, in the Levant, but from the north, in what is today Ukraine and Russia.

COMPLEX HUNTER-GATHERERS

It was the late archaeologist Klaus Schmidt (1953–2014) who was the first to draw comparisons between the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world of Anatolia and the hunting techniques of hunter-gathering societies that thrived on the northern shores of the Black Sea. In particular, he made mention of a tool-making tradition, a so-called technocomplex, known as the Swiderian. So who or what were the Swiderians, and what role might they have played in the emergence of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world of Göbekli Tepe, and through it the rise of western civilization? The Swiderian world emerged during the 2,000-year period of temperature increase known as the Allerød interstadial. This followed the cessation of the last ice age proper around 13,000 BCE and ended abruptly with the Younger Dryas impact event of circa 10,800 BCE.

Powerful elites

There seems every reason to conclude that the Swiderian societies of central and eastern Europe were prime examples of the complex hunter-gatherer system in operation. Forming themselves into “powerful elites,” as Hayden calls them, enabled Swiderian groups to establish trading and bartering networks stretching across many thousands of kilometers, from Poland and the Carpathian Mountains of central Europe to the northern shores of the Black Sea, and eastward across to their suspected original homeland in the western foothills of the Ural Mountains. In all of these territories, they spread their influence, bringing local societies under their wing, not only for trading and bartering purposes but also to exert some form of control over their spiritual well-being.

EPIGRAVETTIAN INDUSTRIES

Swiderian societies of the Crimean Highlands seem particularly significant to this debate since it was here that one of the principal Epipaleolithic populations thrived alongside them at the end of the last ice age. They are known as the Epigravettians, in other words, the terminal form of a much earlier cultural tradition known as the Gravettians, which thrived across Europe circa 33,000 to 22,000 BCE (see chapter 6). In fact, the Swiderian toolkit was so similar to that of the Epigravettians that Australian archaeologist and philologist V. Gordon Childe (1892–1957), one of the twentieth century’s most renowned prehistorians, concluded that the Swiderian industry was a direct survival of the Eastern Gravettian tradition of Russia; they being the precursors of the later Epigravettians as the name suggests.

Such ideas support the observations of Klaus Schmidt, who not only compared Anatolia’s Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture’s hunting techniques with those of European hunter-gathering societies such as the Swiderians, but also suggested that clues regarding the origins of Göbekli Tepe should be looked for among the Epipaleolithic societies situated north of the Black Sea. In making these observations, Schmidt was himself merely echoing the findings of his esteemed colleague, the Turkish prehistorian Mehmet Özdoğan. He too believes that the inspiration behind Anatolia’s Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture derived from the Epigravettian societies of the northern Pontic region, in other words, those of the Crimean Highlands in Ukraine, where some of the principal Swiderian settlements were to be found at that time...

It is important to remember also that all this was going on immediately before and then during the Younger Dryas mini–ice age, when the cold Arctic conditions and extreme dry weather would have driven human populations ever southward in search of more suitable environments in which to live. It is there-fore likely that Swiderian groups would have continued their southward journey, entering southeastern Anatolia some time between 10,500 BCE and 9600 BCE...

WHO BUILT GÖBEKLI TEPE?

The answer to this vexing question is that the actual building and maintenance of Göbekli Tepe was very likely the work of a local populace, one consisting of many hundreds of hunter-gatherers, some almost certainly descendants of the Zarzian culture that had inhabited southeast Anatolia during Epipaleolithic times. The principal architects behind Göbekli Tepe, on the other hand, were, in the opinion of the current author, Swiderian groups from Russia and Ukraine. Arguably, they brought with them knowledge of how to make blades, bladelets and microblades using the pressure technique...

Although we can say very little about the Swiderians themselves, we do know a great deal about their direct successors, the Post-Swiderian cultures of northern, central, and eastern Europe. As we will see next, their cosmological vision of the heavens matches very well that displayed on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43. Yet to establish this relationship, we must shift our attentions, temporarily at least, from southeastern Anatolia to northwestern Russia, in particular an area close to the border with Finland, known as Karelia.

Journeys of the Soul

One of the most important Post-Swiderian cultures was that of the Kunda. They occupied territories from the western foothills of the Urals across to the Baltic forest zone; their open air sites, which can date to anything between 9500 BCE and 5000 BCE, having been found in western Russia, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Finland, and Scandinavia. 1 The Kunda’s largest known cemetery is Yuzhniy Oleniy Ostrov, Southern ReindeerIsland, located within Lake Onega, not far from its eastern shoreline.

Situated in the Russian Republic of Karelia, close to the border with Finland, Lake Onega is Europe’s second largest inland sea. Here, circa 7000–6000 BCE, 2 as many as 170 individuals were interred, many of whom were uncovered during excavations from 1936 to 1938. What is important, however, is that many of the graves were found to contain substantial numbers of bird bones, in particular those belonging to the shoulders, legs, and wings (radii and ulna). Several species are represented, including the osprey, the white-tailed sea eagle, the great gray owl (one example), and various waterfowl, including mallards and whooper swans ( Cygnus cygnus ), the last being represented only by wing bones. Indeed, it has been proposed that to the Kunda the wings of whooper swans “carried some special symbolic significance.”

KARELIAN ROCK ART

That the swan was of special interest to the Kunda culture, or at least its direct Neolithic successors in the northern Baltic region, 12 is apparent also from the presence of rock art seen on exposed surfaces around the northern shores of Lake Onega. Some 1,300 carvings have been dated to the Neolithic age, circa 4200 to 2000 BCE, although the discovery that a large number of the settlements in the vicinity of the rock art date from the Mesolithic age suggests that local rock carving formed part of a long tradition, with its roots in the local Suomusjärvi and Kunda cultures.

A great many of the petroglyphs—around 43 percent on average and up to 60 percent at some locations 14 represent swans or long-necked waterfowl. Some are scaled down in size, others are lifelike, while still others are gigantic, up to 4 meters in length. Mostly, the birds shown are whooper swans, although what appear to be ducks and geese are also present. The necks of the swans are often exaggerated in length and made to look like long poles.

Some of the carvings depict swans with human arms or legs, while still others show anthropomorphic figures with the heads of birds. The discovery of several upright standing burials found in the Yuzhniy Oleniy Ostrov cemetery, suspected to be those of shamans, has led to proposals that the swan-human hybrids found among the rock art of Lake Onega depict shamans who have adopted the guise of the bird to enter the next world.

Cracks and Crevices

Other carvings show swans sitting atop poles that are being climbed by human figures. These perhaps are meant to show the souls of shamans or those of the deceased entering the Upper World via some kind of sky pole or perceived axis mundi, an axis of the earth. In several cases, linear cracks or fissures coincide with the long necks of swans, giving the impression that the birds are either emerging from or disappearing into the other world. This is yet another indication that the swans and the rock art as a whole have a liminal value in that they signify movement between this world and the next. Indeed, according to Antti Lahelma, an archaeologist at the University of Helsinki, “Many of the images of swans at Lake Onega are to be understood as symbols of the soul, or as messengers between the worlds of humans and spirits. Swans entering a crack or emerging from one appear to symbolize the passage of the soul—of a deceased person or a shaman—between this world and the other.”

THE FINNISH “SOUL BIRD”

According to the Finno-Ugric mythology of northwestern Eurasia, which is derived almost certainly from a much older Uralic tradition (that is, it originated among the Uralic-speaking peoples of the Ural Mountains in central-western Russia), migrating birds, swans in particular, are seen to carry the soul into incarnation. Indeed, in Baltic folklore it is the swan that brings babies into the world, not the stork, as is more usual in many other countries of Europe. 1Swans also carried the soul into the afterlife at the moment of death according to Finnish folk tradition. In one mythical account, for instance, the soul of an individual is passed from one swan to another until it reaches a boat waiting by the banks of an otherworldly river. This leads from the physical world to a northerly placed land of the dead called Tuonela, said to be the domain of a beautiful swan.

In Finno-Ugric sky lore, the North Star, as the center of the heavens, was said to be the location of a column that supports the starry vault. As this revolves, it causes a great whirl at the North Pole, and it is through this whirl that human souls gain access to the land of the dead. Almost certainly the long, polelike necks of the swans seen among the rock art at Lake Onega also signify the axis of the earth. Being connected to the celestial pole, it was upon this turning axis of the heavens that the souls of shamans and those of the deceased would climb to reach the afterlife, presumably through a hole in the sky like that found in the shamanic traditions of northern Eurasia.

...The swan-based rock art at Lake Onega almost certainly reflects these same mythological themes, introduced to northwestern Russia and Finland most likely by Uralic-speaking Swiderian or Post-Swiderian groups that entered the region from the vicinity of the Ural Mountains shortly after the retreat of the ice sheets following the cessation of the Younger Dryas event, circa 9600 BCE.

Land of Birds

As seen from the Eurasian and North American continents, the Milky Way is marked at its highest point by the crosslike group of stars identified in Greek Hellenic astronomy as the constellation of Cygnus, the celestial swan (see fig. 5.3). The constellation was most likely identified originally as a swan both from its appearance as a long-necked bird flying along the Milky Way, as well as from the swan’s role as a psychopomp accompanying the human soul into the afterlife. This can then account for why various burials found in Lake Onega’s Yuzhniy Oleniy Ostrov cemetery were accompanied by swan wing bones, for these, as Kristiina Mannermaa and her colleagues suspect, acted as a psychic link between the soul of the deceased and the swan’s spirit in the belief that it would accompany the soul of the individual into the afterlife.

All these ideas were almost certainly introduced to the Mesolithic peoples of northern Europe by Finno-Ugric speaking Swiderian groups, whose own ancestors had come originally from the Ural Mountains, or arguably beyond them in western Siberia. Here, of course, still live the Mansi and Khanty.

Similar Swiderian groups, I suspect, helped catalyze the rise of the PrePottery Neolithic world in southeastern Anatolia. They introduced the widespread use of microblade technology and triggered the construction of the megalithic enclosures at Göbekli Tepe. It can thus be no coincidence that Kurdish, one of the oldest language groups in southwest Asia, contains a number of words that have direct comparisons with those of the Finno-Ugric or Uralic languages of northern and central Europe. It thus seems reasonable to suggest that these language elements were introduced by incoming Uralicspeaking peoples, including Swiderian-linked groups. What is more, even closer links exist between the material culture of the Göbekli builders and the peoples inhabiting the Ural Mountains at the beginning of the Mesolithic age, circa 9600 BCE.

Anthropologist and prehistoric archaeologist Mikhail G. Zhilin of the Institute of Archaeology at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow and his colleagues, in an important paper published in 2018 within the journal Antiquity, draw attention to the design of the Shigir Idol and the anthropomorphic nature of the T-pillars found at Göbekli Tepe, which are all of a similar age. As proposed by the current author elsewhere and intimated also by Zhilin and his colleagues, the advanced culture existing in the Trans-Urals at the end of the Upper Paleolithic Age-early Mesolithic age, circa 9600 BCE, evidenced not just by the Shigir Idol but also by various well-fashioned portable artifacts and two cave sanctuaries with extensive painted art, hint strongly at a cross-cultural link at this time between the inhabitants of the Urals and the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world of Göbekli Tepe.

So is it possible that these incoming Uralic-speaking peoples carried with them cosmological beliefs and practices relating to the transmigration of the soul and its connection with both the Milky Way and the Cygnus constellation?

The Elk in Star Lore

One clue is the fact that the carved relief of Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43 and Lake Onega’s Neolithic rock art both appear to represent the same death journey taken by the soul to reach an afterlife among the stars. Both reflect an interest in the north, and the northern celestial pole in particular, and both feature birds that can be identified with the Cygnus constellation—the vulture at Göbekli Tepe and the swan at Lake Onega in Karelia. What is more, the enigmatic set of petroglyphs on the tiny island of Bolshoy Guri in the northeastern part of Lake Onega, showing a swan along with a filled circle and two elks, is strangely reminiscent of the carved relief on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43. For instance, the circular device in the Lake Onega rock art replicates the filled circle seen on the wing of the vulture on the T-shaped head of Pillar 43...

Vulture, not Swan

The greatest difference between the rock art of Lake Onega and the carved relief on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43 is that in the latter the principal bird featured is the vulture, and not the swan. Why exactly is not difficult to understand. In the Zagros and Taurus mountains of Anatolia and the Near East, vultures, as eaters of the dead, would have had a far greater impact on funerary beliefs and practices related to the soul’s journey to the afterlife. At high altitudes, waterfowl just did not have the same impact on the human psyche, the reason most probably why at places like Göbekli Tepe the vulture became the ultimate psychopomp.

THE SOLUTREAN CONNECTION

When celebrated prehistorian V. Gordon Childe wrote that Swiderian stone tool manufacture was a direct survival of the Eastern Gravettian tradition, as shown at sites like Kostenki in Russia, 1 he also made another important observation. He noted that “Solutrean techniques” of stone tool manufacture were “applied at times to the later Eastern Gravettian (Kostienki) flint-work and survived locally even in the Mesolithic Swiderian industry.” Thus, he recognized a commonality in style between the stone tools made by the Solutreans of southwestern Europe, who thrived circa 20,000 to 15,000 BCE, and those made by later Swiderian and Post-Swiderian societies that occupied many parts of central, northern, and eastern Europe circa 11,500 to 5000 BCE...

Many archaeologists write off the Solutreans as a minor intrusion into European prehistory, their influence lasting no more than a few thousand years. The achievements of the Solutreans, and any lasting impact on the sub-sequent Magdalenian tradition, are seen as negligible. Yet as we shall see next, this was most certainly not the case, for today there is compelling evidence that the Solutreans were responsible for the creation of sculpted relief art with direct comparisons to that found at Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Anatolia some 5,000 years later.

Shaft of the Dead Man

Although the Solutreans do not appear to have contributed greatly to the painted cave art of southwestern Europe, they do seem to have been responsible for the creation of at least some of the ice age frescoes at the Lascaux Cave in the Vézère Valley, within France’s Dordogne region. The cave complex’s 6-meter-deep pit known as the Shaft of the Dead Man, or the well shaft, contains an enigmatic painted panel showing a reclining bird-headed man with an erect penis next to a bird on a pole (see plate 10 ). To the birdman’s right is a bison with a spear in its stomach, exposing the animal’s entrails. Off to the left is a rhinoceros that seems to be walking away from the scene.

FALLING IN TRANCE

The fresco’s location on the north wall of the pit is most likely connected with its fundamental purpose, for the bird on a pole is almost certainly a representation of a cosmic bird on top of a sky pole. Very likely this pole symbolized a connection between the physical world, or indeed the underworld of the cave chamber, and the northern celestial pole in its role as an opening to the Upper World of shamanic tradition. The birdman immediately above the bird on a pole is most likely a shaman who, having achieved a state of trance, is in the process of entering the other world. Supporting this theory is the reclining stance of the birdman, which provides the pit with its name, the Shaft of the Dead Man. In Finno-Karelian shamanism, “falling in trance” is an expression used to describe entry into otherworldly environments, either via clefts in rock faces or via cracks in the ground, like those found in connection with the Post-Swiderian–linked rock art on the rocky shores of Lake Onega. Finno-Karelian shamans also believe that painting or carving images on rock surfaces creates a portal through which they can pass between this world and the next. It is a concept connected also with the presence of porthole stones in the north-northwestern sections of enclosure walls at Göbekli Tepe, which would seem to have been used for the same purpose of exiting the physical world.

Most likely, the Lascaux birdman is himself “falling in trance,” as he appears to be “falling” into the cleft or hollow visible immediately below and to the left of the bird on a pole (see fig. 9.2). The fact that this hole has a long concave depression beyond its upper end, which is aligned toward the birdman, suggests that it acts in the same capacity as the cracks and fissures seen on the shores of Lake Onega. It is through this hole, located in the pit’s north wall, that the Lascaux birdman, or indeed, the soul or spirit of anyone conducting ceremonies in the well shaft, is able to gain access, via the sky pole, to the realm of the cosmic bird.

The purpose of the birdman’s erect penis lies in the sheer fact that erections often occur during the early stages of drug-induced experiences. They are also known to occur at the moment of death, something that might well have been linked with death-like trances brought about by the consumption of dangerous hallucinogens. So in this manner a pictorial representation of a shaman with an erection is conveying the idea that he is in the process of entering a death-like state. This might therefore explain not only the erect penis of the Lascaux birdman, but also that of the headless individual seen riding on the back of the hook-beaked bird on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 43.

Radiocarbon testing of organic materials removed from the Shaft of the Dead Man at Lascaux has provided dates in the region of 16,500 to 15,000 BCE. 3 Thus it seems likely that the cosmic bird in question is the constellation of Cygnus, which coincided with the northern celestial pole circa 15,750 to 12,750 BCE (and arguably for 1,000 years or so before this time). Since a time frame of 16,500 to 15,000 BCE hints strongly at the fact that Solutreans were responsible for this cave art, this tells us that these cosmological notions almost certainly featured in their beliefs and practices.

The Summer Triangle

Archaeoastronomer Michael Rappenglück, Ph.D., of the University of Munich, has proposed that the Lascaux birdman, the bird on a pole, and the nearby bison represent key stars in the vicinity of Cygnus and the Summer Triangle when the former marked the northern celestial pole. 4 This is exactly what Estonian astronomer and scientist Heino Eelsalu concluded as far back as 1985. He wrote that the Lascaux well shaft scene showed cosmological imagery relating to the northern celestial pole as it crossed the Milky Way in the vicinity of the Cygnus constellation, the latter representing a bird of creation. If correct, then it shows that the Solutreans, like the Swiderians thousands of years later, identified the stars of Cygnus as a cosmic bird and saw the northern celestial pole as a point of entry to the sky world. This final assertion seems confirmed in the knowledge that the head of the birdman is more or less identical to that of the bird itself. Both signify the same avian influence. In addition to this, the Solutreans might also have recognized the Milky Way’s well-established role as a road, river, or pathway along which the soul, whether that of the shaman or that of a deceased person, could access this sky portal.

Goose or Duck?

From the bird on a pole’s very basic and somewhat abstract profile (squat body, flat back, curved neck, straight bill, and rounded head), it is perhaps to be identified as a goose or a duck, both of which feature in creation myths found across the Eurasian continent, and also in North America. Moreover, when not identified with a swan, the stars of Cygnus have been identified with a goose, as is recorded in ancient Egypt, Vedic India, Celtic Britain, and also in North America. So in both the Post-Swiderian–inspired rock art of Lake Onega and the well scene at the Lascaux Cave in southwestern France, we can see how a relationship might well have existed between the cosmological beliefs and practices of the Solutreans and those of the later Swiderians and Pre-Pottery Neolithic peoples of southeastern Anatolia. Moreover, there exists even further evidence that both cultures recognized the Cygnus constellation as the entrance to the sky world and origin point of human souls...

THE IDENTITY OF TÜNDÉR ILONA

Tündér Ilona as the swan that brings forth the sun in the form of an egg is very clearly a Hungarian form of Cygnus in its role as the cosmic bird, meaning that she can also be equated with the bird on a pole in France’s Lascaux Cave. More than this, Ilona also has similarities to the Estonian swan goddess Linda or Lindu. This is confirmed in the knowledge that in both Estonian and Hungarian mythology the Milky Way is said to be the trail of the goddess’s veil. Tündér Ilona can be equated also with the swan of Finno-Ugric myth who brings forth the universe in the form of an egg, a myth seemingly expressed in the swan imagery at Lake Onega and echoed as far away as ancient Egypt in the story of the god Geb taking the form of the goose Gengen-wer (“Great Cackler”) to bring forth both the universe and the sun god from an egg laid by him.

Many other similar stories involving either a swan or a goose bringing forth the universe and/or the physical world are found in northern Asia, showing the widespread dissemination of these myths across the Eurasian continent. They are even present in North America. For instance, in Cherokee tradition, the bird that brought forth the universe in the form of an egg is Guwisguwi, a large white water bird with the appearance of a swan. In Cherokee star lore, Guwisguwi is identified with the Cygnus star Deneb. He is shown on the top of a T-shaped device symbolizing a sky pole supporting the Upper World (see fig. 9.5), a theme that once again echoes the bird on a pole seen in the Shaft of the Dead Man in France’s Lascaux Cave.

THE INFLUENCE ON GÖBEKLI TEPE

The importance of this exercise is to demonstrate that cygnocentric and polar-centric cosmological ideas, that would appear to have flourished at the same time that the Solutreans occupied southwestern Europe, eventually found their way via carrier cultures such as the Swiderians all the way from the Ural Mountains to Anatolia. Here, sometime around 9600 BCE, they were adopted by its Pre-Pottery Neolithic world. This included the belief that the soul’s journey to the land of the dead was connected with the Milky Way and Cygnus constellation, which last synchronized with the northern celestial pole circa 15,750 to 12,750 BCE. Guarding the entrance to the land of the dead at Göbekli Tepe was a cosmic bird, exactly as we find in northern, central, and western Europe. Yet in southwestern Asia, the vulture, the ultimate symbol of the dead and rebirth in Pre-Pottery Neolithic tradition, replaced the migrating swans or geese of more northerly climes. However, their function was exactly the same: they guided and protected the soul on its journey to an afterlife accessed via the northern celestial pole, and also, most likely, acted as symbols both of cosmic creation and the emergence into the physical world of human souls.

Beyond these assumptions is the tantalizing connection between the carved stone friezes and sculpture of the Solutreans and the carved art seen on the decorated T-pillars and porthole stones found at Göbekli Tepe. Prior to the emergence of Anatolia’s Pre-Pottery Neolithic world some 11,500 years ago, the only recognized two-dimensional bas-relief and three-dimensional rock sculpture that might in any way be compared to that seen at Göbekli Tepe were those created at Solutrean sites in the Franco-Cantabrian region of France and Spain. Last, we have the beautiful trifacial projectile points manufactured by the Solutreans of southwestern Europe and found also at Göbekli Tepe (see chapter 6). So unique in style are these points, which in both instances have been finished using the pressure technique, that to deny some kind of continuity, whether it be direct or indirect, would be foolish indeed.

To be continued.