https://aeon.co/essays/gandhi-was-a-subtle-surprising-philosopher-in-the-stoic-style

This article was in interesting find given the current recommended reading around philosophy and history - at least Collingwood's "The Idea of History" since that's what I'm reading now.

If anyone can vouch for its accuracy it seems like a good piece of information and explanation regarding Ghandi. In addition to the following, there is some interesting comparison of Ghandi's views with the Stoics' regarding good conduct and Will:

This article was in interesting find given the current recommended reading around philosophy and history - at least Collingwood's "The Idea of History" since that's what I'm reading now.

If anyone can vouch for its accuracy it seems like a good piece of information and explanation regarding Ghandi. In addition to the following, there is some interesting comparison of Ghandi's views with the Stoics' regarding good conduct and Will:

In 1926, Gandhi wrote a series of eight newspaper articles, including an English version, under the title ‘Is This Humanity?’, in which he refined his conception of non-violence. In particular, he addressed the question: when is killing non-violent? This question was triggered by his support of the head of a municipality, who had authorised the killing of 60 stray dogs for fear that they might spread rabies. Outraged letters came to Gandhi from all over India, saying: ‘We thought you were a man of non-violence.’

Gandhi offered a model of philosophical reaction. He published a number of the letters in his newspapers, not concealing, nor misrepresenting, the criticisms, although he allowed himself a witticism: that one of the letters demanding non-violence was violent. Nonetheless, Gandhi sought to rethink his position, in order to provide an answer, and by the end of the third article offered a new criterion. Killing was always violent, unless it was done for the sake of the killed. Was that not an admission that he was in the wrong, since killing the stray dogs was not for their sake, although it might have been for the sake of other dogs, and people? But he had already, in the first article, made an important philosophical point:

A city-dweller who is responsible for the protection of lives under his care … is faced with a conflict of duties. If he kills the dog, he commits a sin. If he does not kill it, he commits a graver sin. So he prefers to commit the lesser one and save himself from the greater.

In other words, it was wrong to kill the dogs, because one is sometimes, through no fault of one’s own, in a moral double-bind: wrong if one does and wrong if one doesn’t. This was known to the ancient Greeks, but resisted for a long time by Christianity. In the Greek story, Orestes was in a moral double-bind: wrong if he did not avenge his father by killing the assassin, but wrong if he killed his mother, who was the assassin. Christianity at first found this hard to accept, because eternal punishment was expected for serious wrongdoing and, since God was just, the wrongdoing needed to be one’s fault. As a result, in the 6th century CE, elaborate attempts were made to locate a fault. But Gandhi saw that sometimes choosing violence is not one’s fault. He nonetheless continued to hold that all violence was wrong, and was not even tempted by the implausibly lenient idea that, if something is not one’s fault, it can only be apparently wrong, prima facie.

This in turn meant that although Gandhi admits a few exceptionless moral principles (in this case, all chosen violence is wrong), he does not think that exceptionless principles can on their own guide us on conduct – they do not tell us what to do, since we might have personal duties, a svadharma such as responsibility for municipal welfare, that would make the non-violent course the worse one for us. Gandhi might think that certain attitudes, such as non-violence as compassion, are universally desirable. But even so, he does not aim to alter the attitude, or the conduct, of those Muslims who believed instead in retaliation.

[snip]

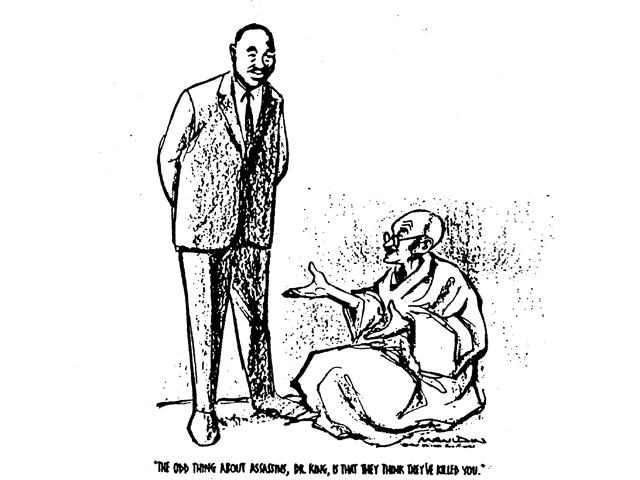

I have already given an example to show why I think Gandhi’s philosophy needs to be studied if his politics are to be understood. It is not opportunism that he sometimes allows violence yet often forbids it too. His belief is subtle (and, to my mind, correct) that, although violence is always wrong, it does not give us exceptionless laws of how to act.

[snip]

To read Gandhi, then, is to read a great spiritualist who inspired new ideals across the world – and a great tactician. But my point has been that it is also to read someone who provides a model for philosophical thinking.