Ocean

The Living Force

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/7664064.stm

Thai political crisis at fever pitch

By Jonathan Head

BBC News, Bangkok

When doctors decide to violate their Hippocratic Oaths, and refuse to treat injured police officers, you know things are bad.

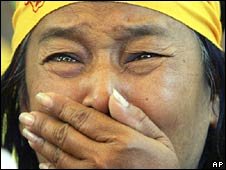

Emotions are raw on each side of the political divide

That is what's happening in Thailand right now, so much so that the world financial meltdown, which will surely affect Thailand just as badly as any other export-dependent Asian economy, is scarcely being noticed.

The deadlock between the government, still led by close allies of one-time Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, and its opponents, spearheaded by the well-funded People's Alliance for Democracy protest movement, has been going on for months.

It is actually a continuation of a political crisis that began two years into Mr Thaksin's second term of office, in early 2006, when the hugely profitable sale of his family's business empire sparked mass demonstrations, which eventually led to the coup that forced him from power in September that year.

Events over the past three years have only hardened the positions of both sides.

Mr Thaksin's supporters, most of them in the rural north and north-east, still see him as a champion who pushed through policies that made real improvements to their lives. They felt robbed by the coup, and insulted by the PAD protesters who say their votes for Mr Thaksin were bought.

Mr Thaksin's opponents still see him, even in exile, as a dangerous politician of overreaching ambition, a man who used his wealth to concentrate power in his hands, and who had a hidden republican agenda.

But emotions have never been as raw as they are now.

The violent clashes on Tuesday - the worst since 1992 - have prompted furious accusations from the PAD and its many sympathisers that the police used excessive force, and that the government was being deliberately provocative in sending them in to clear the protesters who had surrounded parliament.

Thai websites are running gruesome video clips showing horrific injuries. These, say the PAD, could not have been caused by just teargas; the police must have been firing other explosives as well, they say.

Media quiet

There is little doubt that the police were reckless in the way they moved against the protesters.

But there has been surprisingly little condemnation in the Thai media of the PAD's own tactics: the construction of tyre-and-barbed-wire barricades to blockade MPs inside parliament, the use of guns by some PAD supporters against the police, video showing a PAD truck ploughing into a line of police then reversing over the injured body of one officer.

The protesters' tactics have been subject to little scrutiny

There has been no attempt by the Thai papers to trace the source of the PAD's very substantial funding, or of the obviously expert paramilitary training given to some its followers.

It is true there is little public affection for Thailand's corrupt police force, and even less, in Bangkok, for the members of the new cabinet, who astonishingly seems even less convincing than their inept predecessors.

Fence

Prime Minister Somchai Wongsawat, who won some praise for his conciliatory statements after being appointed last month, has appeared weak and indecisive in his response to the violent events around parliament.

The fact that he had to climb over a fence to escape from the PAD protesters around the parliament building did not help his image much.

But there is something else afoot here.

Thais now have so little faith in their politicians and institutions that a substantial number are willing to overlook the PAD's brazenly illegal activities.

Conspiracy theories and wild rumours abound, with each side willing to believe the most outlandish stories about its opponents. This is worrying, in what is normally one of the world's more peaceful societies.

Most worrying is the absence of any obvious way out of the deadlock.

And there is one figure conspicuous by his silence.

In times past King Bhumibol Adulyadej has used his unrivalled moral authority to settle such crises. There are many Thais who wish he would intervene now.

But the 80-year-old monarch has said nothing. His only recent public statements have been an expression of concern over coastal erosion, and a reminder to a new crop of judges to be honest. So little is seen or heard of the king these days that it is impossible to guess what his thoughts are on this crisis.

But his silence makes the prospect of a royally endorsed government of national unity under an appointed prime minister - one possible solution touted by some - more remote.

A military coup seems unlikely too, although in Thailand it can never be ruled out.

Army stands back

There have been several occasions over the past few weeks when rumours of military intervention have swirled around Bangkok; Gen Anupong Paochinda, the army commander, has squashed them all.

Army commander Gen Anupong Paochinda

Army chief Gen Anupong has seen his standing improve in the crisis

He argues persuasively that the military did not resolve the political rifts by intervening with its coup two years ago, and that it cannot solve the problem now. There are believed to be senior officers who think otherwise, but their views have not prevailed.

Besides, while Gen Anupong stays out of the fray, occasionally sending his men in, unarmed, to clean up where the police have lost control, his image and that of the army is further burnished. He has also been able to bargain for a hugely increased budget for the military. No government now would dare refuse him.

No one expects this government to last long, but no one has come up with a workable alternative.

Another election would almost certainly lead to little change. The People Power Party, the reincarnation of Thaksin Shinawatra's Thai Rak Thai, still commands sufficient loyalty in the rural north and north-east to beat the opposition Democrats. Even the Democrats admit this.

So Mr Somchai will soldier on in the job.

And however hard he tries, he remains hopelessly bound by his unappealing cabinet, and the fact that he is Mr Thaksin's brother-in-law and is therefore widely assumed to be working to protect the exiled former prime minister and engineer his eventual return to Thailand.

Thai political crisis at fever pitch

By Jonathan Head

BBC News, Bangkok

When doctors decide to violate their Hippocratic Oaths, and refuse to treat injured police officers, you know things are bad.

Emotions are raw on each side of the political divide

That is what's happening in Thailand right now, so much so that the world financial meltdown, which will surely affect Thailand just as badly as any other export-dependent Asian economy, is scarcely being noticed.

The deadlock between the government, still led by close allies of one-time Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, and its opponents, spearheaded by the well-funded People's Alliance for Democracy protest movement, has been going on for months.

It is actually a continuation of a political crisis that began two years into Mr Thaksin's second term of office, in early 2006, when the hugely profitable sale of his family's business empire sparked mass demonstrations, which eventually led to the coup that forced him from power in September that year.

Events over the past three years have only hardened the positions of both sides.

Mr Thaksin's supporters, most of them in the rural north and north-east, still see him as a champion who pushed through policies that made real improvements to their lives. They felt robbed by the coup, and insulted by the PAD protesters who say their votes for Mr Thaksin were bought.

Mr Thaksin's opponents still see him, even in exile, as a dangerous politician of overreaching ambition, a man who used his wealth to concentrate power in his hands, and who had a hidden republican agenda.

But emotions have never been as raw as they are now.

The violent clashes on Tuesday - the worst since 1992 - have prompted furious accusations from the PAD and its many sympathisers that the police used excessive force, and that the government was being deliberately provocative in sending them in to clear the protesters who had surrounded parliament.

Thai websites are running gruesome video clips showing horrific injuries. These, say the PAD, could not have been caused by just teargas; the police must have been firing other explosives as well, they say.

Media quiet

There is little doubt that the police were reckless in the way they moved against the protesters.

But there has been surprisingly little condemnation in the Thai media of the PAD's own tactics: the construction of tyre-and-barbed-wire barricades to blockade MPs inside parliament, the use of guns by some PAD supporters against the police, video showing a PAD truck ploughing into a line of police then reversing over the injured body of one officer.

The protesters' tactics have been subject to little scrutiny

There has been no attempt by the Thai papers to trace the source of the PAD's very substantial funding, or of the obviously expert paramilitary training given to some its followers.

It is true there is little public affection for Thailand's corrupt police force, and even less, in Bangkok, for the members of the new cabinet, who astonishingly seems even less convincing than their inept predecessors.

Fence

Prime Minister Somchai Wongsawat, who won some praise for his conciliatory statements after being appointed last month, has appeared weak and indecisive in his response to the violent events around parliament.

The fact that he had to climb over a fence to escape from the PAD protesters around the parliament building did not help his image much.

But there is something else afoot here.

Thais now have so little faith in their politicians and institutions that a substantial number are willing to overlook the PAD's brazenly illegal activities.

Conspiracy theories and wild rumours abound, with each side willing to believe the most outlandish stories about its opponents. This is worrying, in what is normally one of the world's more peaceful societies.

Most worrying is the absence of any obvious way out of the deadlock.

And there is one figure conspicuous by his silence.

In times past King Bhumibol Adulyadej has used his unrivalled moral authority to settle such crises. There are many Thais who wish he would intervene now.

But the 80-year-old monarch has said nothing. His only recent public statements have been an expression of concern over coastal erosion, and a reminder to a new crop of judges to be honest. So little is seen or heard of the king these days that it is impossible to guess what his thoughts are on this crisis.

But his silence makes the prospect of a royally endorsed government of national unity under an appointed prime minister - one possible solution touted by some - more remote.

A military coup seems unlikely too, although in Thailand it can never be ruled out.

Army stands back

There have been several occasions over the past few weeks when rumours of military intervention have swirled around Bangkok; Gen Anupong Paochinda, the army commander, has squashed them all.

Army commander Gen Anupong Paochinda

Army chief Gen Anupong has seen his standing improve in the crisis

He argues persuasively that the military did not resolve the political rifts by intervening with its coup two years ago, and that it cannot solve the problem now. There are believed to be senior officers who think otherwise, but their views have not prevailed.

Besides, while Gen Anupong stays out of the fray, occasionally sending his men in, unarmed, to clean up where the police have lost control, his image and that of the army is further burnished. He has also been able to bargain for a hugely increased budget for the military. No government now would dare refuse him.

No one expects this government to last long, but no one has come up with a workable alternative.

Another election would almost certainly lead to little change. The People Power Party, the reincarnation of Thaksin Shinawatra's Thai Rak Thai, still commands sufficient loyalty in the rural north and north-east to beat the opposition Democrats. Even the Democrats admit this.

So Mr Somchai will soldier on in the job.

And however hard he tries, he remains hopelessly bound by his unappealing cabinet, and the fact that he is Mr Thaksin's brother-in-law and is therefore widely assumed to be working to protect the exiled former prime minister and engineer his eventual return to Thailand.