Being somewhat of a chronic worrier in the past I though some discussion of worry might be useful.

It dove tails nicely with the thread on accepting your emotional/physical state 'as is'.

It will eat up your energy in minutes. You can get the energy back if you change your perspective.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/insight-therapy/201501/how-stop-worrying-and-get-your-life

Having read all that, how many of you are now worrying about worrying?

If so, you need to be treating it like an addiction and using mindful elf compassion and balancing brain chemicals to change things.

http://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2013/04/03/how-to-stop-worrying-about-worrying/

http://tinybuddha.com/blog/overcoming-approval-addiction-stop-worrying-people-think/

It dove tails nicely with the thread on accepting your emotional/physical state 'as is'.

It will eat up your energy in minutes. You can get the energy back if you change your perspective.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/insight-therapy/201501/how-stop-worrying-and-get-your-life

How to Stop Worrying and Get on With Your Life

An expert explains why worries spiral out of control, and how to stop them.

Post published by Noam Shpancer Ph.D. on Jan 02, 2015 in Insight Therapy

“Worrying,” quipped Mark Twain, “is like paying a debt you don't owe.” {If you believe you are worthless, Not deserving of compassionate understanding and kindness, especially from yourself then 'paying a debt you don't owe' is pretty normal! The 'dept' is the belief you hold, and it is an energy drain} Worry features in many people’s lives. In mild form, occasional worry may serve a helpful coping function, getting us to think and plan ahead. At higher volume and frequency, worry can become annoying and distracting, and may undermine our productivity, concentration, and mood. At extremely high levels, chronic worry can derail your life. Such worry also constitutes the central symptom of a common psychological disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (link is external) (GAD).

GAD runs in families and appears to have a substantial genetic component (link is external). It is often diagnosed together with depression (link is external) and other anxiety disorders. This is why some psychologists believe it represents an underlying constitutional vulnerability, a general "anxious apprehension" process that may at times manifest itself through different specific fears, such as fears of certain objects (specific phobia), of social judgment (social phobia), of physiological arousal symptoms (panic disorder), or of troubling thoughts and images (OCD).

Worry is a devious foe for several reasons. First, people who worry a lot most often see their worries come to naught. In other words, most imagined catastrophic scenarios don’t actually materialize. One would think that a system (worry) that constantly fails at its job (predicting the future) would be abandoned. Instead, the opposite usually happens. This is because our brains tend to confuse correlation with causation. In this case, since worry is associated with things turning out OK, worriers begin to believe that it is the worry what made things turn out OK—which is in fact false; research shows that worry hinders rather than facilitates effective problem solving. Hence, worriers tend to increase their worrying in response to their failed predictions of catastrophe. Over time, worry morphs from a habit into a requirement born of superstition. {It should be noted that this can stem from avoiding feelings of powerlessness, vulnerability and generally seeing 'needing help from others' as weak}

In addition, research has suggested that although worry is associated with health and coping problems in the long term, it tends to decrease physiological (fight-or-flight) arousal in the short term. In this way, worrying works somewhat like an addictive drug—it provides short term stress relief through avoidance and is hence experienced as rewarding. Since our brain is wired to privilege short term rewards, a worry cycle is easily established that is as difficult to break as drug addiction. Like a drug, worry itself over time becomes a bigger problem than whatever concerns it ostensibly addresses. {Balancing brain chemicals can help greatly with any addiction, see the mood cure}

Another difficulty is that for those who have developed the habit of continual worry, the experience of not worrying is novel and disconcerting. As such, it becomes a source of worry in itself: “Why am I not worried? Something must be wrong with me!” Old habits die hard, and even after they die, they often hang around as scary ghosts.

Still, when worry becomes chronic, frightening, and debilitating we may be moved to do something about it. In the past, thought suppression techniques were advanced as one solution. The evidence, however, suggests that thought suppression (link is external) is an ineffective way to deal with constant worry, and may have the ironic effect of magnifying worry and its influence. Instead of suppressing, denying, or trying to avoid those nagging thoughts, it is more useful to engage them in conversation, where they may be more closely examined in the light of real world evidence. {Trying to suppress acknowledgment of thoughts and feelings in my experience never works and does make them stronger - it depletes Will and energy when a more balanced approach wastes no energy fighting yourself. This leaves Will power available in order to choose to act.}

In this context, research by David Barlow and others (link is external) has identified two main cognitive distortions that characterize worry. First, worry tends to involve an “overestimation bias,” whereby the odds of the worried-about scenario materializing are invariably imagined to be high. In other words, the "voice of worry" ignores actual probabilities and always predicts imminence. Second, worry involves a “catastrophizing bias,” whereby the consequences of the worried-about scenario are imagined to be negative in the extreme. The voice of worry ignores gradations and always predicts the absolute worst. {black and white thinking, which is a sign that the mind is operating in 'danger mode' and is likely fighting off 'dangerous emotions'}

While worried-about scenarios tend to appear in our minds as both imminent and extremely bad, in real life not all scenarios are bad, and even bad scenarios are not always imminent and/or extreme. This distinction matters, because living necessarily requires taking on low probability risk, every single day. For example, when you step into the shower in the morning, you may slip and break your neck. But most people still take on the risk. Why? Because the odds of it actually happening are low. Accurately calculating whether the odds of something happening are high or low is crucial to our daily decision-making. In general, low-probability risk scenarios are disregarded so that we can go about our daily business. High-probability risk scenarios may be defended against, or avoided. {Are you a worrier or anxious? Find that you can't start projects or posts? That's because the risk has been labeled 'catastrophic' and so the action is avoided}

Similarly, not all negative eventualities in life are extreme. In fact, extreme catastrophes are rare. (If they were common, then they would not in all likelihood be considered extreme.) An event’s level of impact makes a difference in the real world—getting hit by a bullet is different from being hit by a paint ball.

Given the distorted tendency of the voice of worry to make all risks appear likely and catastrophic, and given the real life importance of estimating the actual likelihood and severity of risks, the internal conversation regarding worry should include two main questions:

1) How likely is it, really? This question addresses the error of overestimation. An honest consideration of the actual odds that the negative scenario will materialize will help us distinguish justified, useful concern (high odds) from unjustified, useless worry (low odds).

2) How bad is it, really? (link is external) This question addresses the error of catastrophizing. It helps us consider the evidence in distinguishing the extreme, real threat (a bullet) from the non-extreme, benign threat (a paint ball).

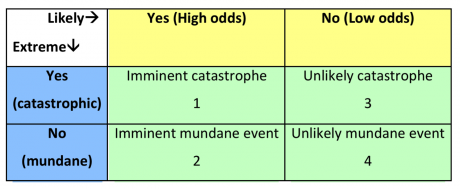

Now, these two questions, considered in tandem, may be represented in a 2 x 2 matrix of the kind psychologists love to draw:

{A note here, if you are unable to extract yourself from worry in order to analyse it you need tools and practice in order to do so. Practicing body awareness is the first place to begin, as it 'takes you out of your mind'. Yoga and massage are useful for this. You may also need to balance your brain chemicals.}

As seen in the table, three of the four cells constitute good news. Specifically, an event that is imminent but mundane (2) need not be terribly bothersome. Such events are not the end of the world; they are just the world. An event that is catastrophic but unlikely (3) may also be disregarded—as such events must be in the course of pursuing our most basic daily tasks, unless we’re willing to go without bathing forever. And clearly, an unlikely mundane event (4) is of no concern at all. Once your worries are fleshed out and evaluated, it becomes clear that, contrary to the distortions inherent in the voice of worry, most high likelihood events are not terrible, and most terrible events are not likely.

Now, it is important to emphasize that in engaging the inner conversation with our voice of worry, we are not looking to counter negative thoughts with positive thoughts. Instead, we are looking to counter inaccurate thoughts with accurate thoughts; to replace lies with truths. {Right here we see a very practical example of the Work we can do on ourselves, perhaps with the help of objective feedback from others} Therefore, we must accept the possibility that once in a long while we will face an imminent and catastrophic event (1). That’s life. But recognizing that life is fragile and fleeting is, if anything, a very good reason to forsake needless worrying and start living.

To paraphrase Charles Darwin, anyone who dares to waste one hour of time worrying has not discovered the value of life.

Having read all that, how many of you are now worrying about worrying?

If so, you need to be treating it like an addiction and using mindful elf compassion and balancing brain chemicals to change things.

http://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2013/04/03/how-to-stop-worrying-about-worrying/

How to Stop Worrying about Worrying By Therese J. Borchard

Associate Editor

Sir Winston Churchill, who battled plenty of demons, once said, “When I look back on all these worries, I remember the story of the old man who said on his deathbed that he had a lot of trouble in his life, most of which had never happened.”

Unfortunately that advice wouldn’t have been able to stop me from praying rosary after rosary when I was in fourth grade to avert going to hell, nor does it quiet the annoying noise and chatter inside my brain today in any given hour. But the fact that a great leader battled the worry war does provide me some consolation.

It doesn’t matter whether you are a chronic worrier without an official diagnosis or battling severe obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), a neurobehavioral disorder that involves repetitive unwanted thoughts and rituals. The steps to overcome faulty beliefs and develop healthy patterns of thinking are the same.

Worrying about facing the inferno as a 10-year-old and fretting about whether or not I’ll provide enough income to keep my kids in private school stems from the same brain abnormality that Jeffrey M. Schwartz, M.D. describes in his book, Brain Lock.

When we worry, the use of energy is consistently higher than normal in the orbital cortex, the underside of the front of the brain. It’s working overtime, heating up, which is exactly what is the PET scans show. Too many “what if’s” and your orbital cortex as shown in a PET scan will light up in beautiful neon colors, like the walls of my daughter’s bedroom. However, with repeated cognitive-behavioral exercises, you can cool it down and return your PET scan to the boring black and white.

In their book, The OCD Workbook, Bruce M. Hyman, Ph.D., and Cherry Pedrick, RN, explain the ABCDs of faulty beliefs. It’s a four-step cycle of insanity:

A = Activity Event and Intrusive Thought, Image or Urge. (What if I didn’t lock the door? What if I upset her? I know I upset her.)

B = Faulty Belief About the Intrusive Thought. (If I don’t say the rosary, I’m going to hell. If I made a mistake in my presentation, I will get fired.)

C = Emotional Consequences: Anxiety, Doubt, and Worry. (I am a horrible person for upsetting her. I keep making mistakes … I will never be able to keep a job. I hate myself.)

D = Neutralizing Ritual or Avoidance. (I need to say the rosary to insure I’m not going to hell. I should avoid my friend who I upset and my boss so that he can’t tell me I’m fired.)

{Right here we can see that the pattern of 'worry' is about avoiding 'potential future pain' - and underneath that it's actually about avoiding emotional pain. Worrying may give you enough of a chemical hit to the brain to temporarily alleviate emotional pain}

Those might seem extreme for the casual worrier, but the small seed of anxiety doesn’t stay small for long in a person with an overactive orbital cortex.

Hyman and Pedrick also catalog some typical cognitive errors of worriers and persons with OCD:

* Overestimating risk, harm, and danger

* Overcontrol and perfectionism

* Catastrophizing

* Black-and-white or all-or-nothing thinking

* Persistent doubting

* Magical thinking

* Superstitious thinking

* Intolerance of uncertainty

* Over-responsibility

* Pessimistic bias

* What-if thinking

* Intolerance of anxiety

* Extraordinary cause and effect

One of the best approaches to manage a case of the worries and/or OCD is the four-step self-treatment method by Schwartz, explained in Brain Lock,

Step 1: Relabel.

In this step you squeeze a bit of distance between the thought and you. By relabeling the bugger as “MOT” (my obsessive thought) or something like that, you take back control and prevent yourself from being tricked by the message. {If you identify with it you are lost in the thought loops, so 'step back' and see it as 'part of you' but not All of you} Because I’ve always suffered from OCD, I remind myself that the illogical thought about which I’m fretting is my illness talking, that I’m not actually going insane.

Step 2: Reattribute.

Here is where you remember the PET scan that would look like your brain. By considering that colorful picture, you take the problem from your emotional center to your physiological being. This helps me immensely because I feel less attached to it and less a failure for being able to tame and keep it under control. Just like arthritis that is flaring up, I consider my poor, overworked orbital cortex, and I put some ice on it and remember to be gentle with myself.

Step 3: Refocus.

If it’s at all possible, turn your attention to some other activity that can distract you from the anxiety. Schwartz says: “By refusing to take the obsessions and compulsions at face value—by keeping in mind that they are not what they say they are, that they are false messages—you can learn to ignore or to work around them by refocusing your attention on another behavior and doing something useful and positive.”

{Remember that blocking things out doesn't necessarily help, but you need to have control of your emotional center and over-reactive brain in order to be able to face things}

Step 4: Revalue.

This involves calling out the unwanted thoughts and giving yourself a pep talk on why you want to do everything you can to free yourself from the prison of obsessive thinking. You are basically devaluing the worrying as soon as it tries to intrude.

http://tinybuddha.com/blog/overcoming-approval-addiction-stop-worrying-people-think/

Overcoming Approval Addiction: Stop Worrying About What People Think

By Derek Doepker

“What you think of me is none of my business.” ~Wayne Dyer

Do you ever worry about what people think about you?

Have you ever felt rejected and gotten defensive if someone criticized something you did?

Are there times where you hold back on doing something you know would benefit yourself and even others because you’re scared about how some people may react?

If so, consider yourself normal. The desire for connection and to fit in is one of the six basic human needs according to the research of Tony Robbins and Cloe Madanes. Psychologically, to be rejected by “the tribe” represents a threat to your survival. {So worry is 'planning ahead' to ensure your survival! Except it leaves you paralyzed.}

This begs the question: “If wanting people’s approval is natural and healthy, is it always a good thing?”

Imagine for a moment what life would be like if you didn’t care about other people’s opinions. Would you be self-centered and egotistical, or would you be set free to live a life fulfilling your true purpose without being held back by a fear of rejection?

{If you free up Will power from fighting with yourself, you have more Will to be able to choose what you want to do}

For my entire life I’ve wrestled with caring about other people’s opinions.

I thought this made me selfless and considerate. While caring about the opinion of others helped me put myself into other people’s shoes, I discovered that my desire, or more specifically my attachment to wanting approval, had the potential to be one of my most selfish and destructive qualities.

Why Approval Addiction Makes Everyone Miserable

If wanting the approval of others is a natural desire, how can it be a problem? The problem is that, like any drug, the high you get from getting approval eventually wears off. If having the approval of others is the only way you know how to feel happy, then you’re going to be miserable until you get your next “fix.”

What this means is that simply wanting approval isn’t the problem. The real issue is being too attached to getting approval from others as the only way to feel fulfilled. To put it simply, addiction to approval puts your happiness under the control of others.

Because their happiness depends on others, approval addicts can be the most easily manipulated. I often see this with unhealthy or even abusive relationships. All an abuser has to do is threaten to make the approval addict feel rejected or like they’re being selfish, and they’ll stay under the abuser’s spell.

Approval addiction leads to a lack of boundaries and ultimately resentment. Many times I felt resentment toward others because they crossed my boundaries, and yet I would remain silent. I didn’t want to come across as rude for speaking up about how someone upset me.

The problem is this would lead to pent up resentment over time, because there’s a constant feeling that people should just “know better.” When I took an honest look at the situation, though, I had to consider whose fault it was if resentment built up because my boundaries were crossed.

Is it the fault of the person who unknowingly crossed those boundaries, or the person who failed to enforce boundaries out of fear of rejection?

Looking at my own life, I actually appreciate when someone I care about lets me know I’ve gone too far. It gives me a chance to make things right. If I don’t let others know how they’ve hurt me because of fear of rejection, aren’t I actually robbing them of the opportunity to seek my forgiveness and do better?

This leads me to my final point, approval addiction leads to being selfish. The deception is that the selfishness is often disguised and justified as selflessness.

As a writer, I’m exposed to critics. If I don’t overcome a desire for wanting approval from everyone, then their opinions can stop me from sharing something incredibly helpful with those who’d benefit from my work.

Approval addiction is a surefire way to rob the world of your gifts. How selfish is it to withhold what I have to offer to others all because I’m thinking too much about what some people may think of me?

As strange as it sounds, doing things for others can be selfish. On an airplane, they say to put the oxygen mask on yourself before putting it on a child. This is because if the adult passes out trying to help the child, both are in trouble.

In much the same way, approval addiction can lead a person to martyr themselves to the point that everyone involved suffers.

For instance, if a person spends so much time helping others that they neglect their own health, then in the long run, it may be everyone else who has to take care of them when they get sick, causing an unnecessary burden.

Selfless acts, done at the expense of one’s greater priorities, can be just as egotistical and destructive as selfish acts.

How to Overcome Approval Addiction

The first way to overcome approval addiction is to be gentle with yourself. Wanting to feel connected with others is normal. It’s only an issue when it’s imbalanced with other priorities like having boundaries.

What approval addicts are often missing is self-approval. We all have an inner critic that says things like, “You’re not good enough. You’re nothing compared to these people around you. If you give yourself approval, you’re being selfish.”

You can’t get rid of this voice. What you can do is choose whether or not to buy into it or something greater.

You also have a part of yourself that says, “You’re worthy. You’re good enough. You’re just as valuable as anyone else.” The question becomes: “Which voice do I choose to align to?”

This often means asking yourself questions like, “Can I give myself some approval right now? What is something I appreciate about myself?” The next step is to then be willing to actually allow yourself to receive that approval.

To break approval addiction, remember to treat yourself the way you want others to treat you.

In much the same way, you can overcome approval addiction by equally valuing other important things, such as your need for significance and control. While wanting to control things can be taken too far just like wanting approval, it is the Yang to approval-seeking’s Yin. Both are necessary for balance.

Questions that typically help me are: “Do I want other people’s opinions to have power over me? Would I rather let this person control me or maintain control over my own life?” {Or your own inner critic and worries that are stopping you from acting?}

Finally, there is the ultimate key to overcoming approval addiction. It’s by using the greatest motivator— unconditional love.

Worrying about what other people think masquerades as love. In reality, when you really love someone, you’re willing to have their disapproval.

Imagine a parent with a child. If the parent is too concerned about the child’s opinion of them, they might not discipline their child for fear of the child disliking them.

Have you ever seen a parent who lets their child get away with anything because they don’t want to be the “bad guy?” Is this truly loving? {Consider this dynamic internally, do you get angry and hate yourself for not having will power - yet won't have an honest conversation with yourself?}

To break approval addiction, I realized I had to ask one of the most challenging questions anyone could ask themselves: Am I willing to love this person enough to have them hate me?

If you really care for someone, telling them, “You’re screwing up your life” and having them feel the pain of that statement might be the most loving thing you can do.

This comes with the very real possibility they will reject you for pointing out the truth. However, if you love someone, wouldn’t you rather have them go through a little short-term pain in order to save them a lot of pain down the road? {This includes yourself!}

On the upside, many people will eventually come to appreciate you more in the long term if you’re willing to be honest with them and prioritize your love for them over your desire for their approval.

If you have to share a harsh truth, a mentor, Andy Benjamin, taught me that you can make this easier by first asking, “Can I be a true friend?” to let them know what you’re about to say is coming from a place of love.

—

I’ve found that everything, including the desire for approval, can serve or enslave you depending on how you respond to it.

Do you use your desire for approval as a force to help you see things from other people’s perspective, or do you use it as a crutch on which you base your happiness?

Do you use your desire for approval as a reminder to give yourself approval, or do you use it as an excuse to be miserable when others don’t give you approval?

Finally, are you willing show the ultimate demonstration of genuine love—sacrificing your desire for approval in order to serve another?