Someone else may think of a better title for this thread where I am going to work on defining FOTCM theology and anthropology and how that could and should personally guide each member. This topic is inspired by the recent Cs session of 25 March 2017, to wit:

I think it is necessary to give some background on the ideas and the model I'm going to present here. Throughout, I'll be comparing systems; however, I don't want to overwhelm the reader with more than they need at this point, so I'm going to try to keep it simple.

First, it would be helpful if the reader has read the Secret History series: "The Secret History of the World and How to Get Out Alive", "Comets and the Horns of Moses", "Earth Changes and the Human-Cosmic Connection". In "Comets", I discussed ancient Greek philosophy at some length, with particular emphasis on the Stoics.

In studying ancient religions and philosophical systems (they were often overlapping or one and the same thing in a certain sense), the main questions of modern scholars are how to categorize the different ideas that appear: are they theological, that is, the "systematic study of the divine and the exploration of religious truths", which usually includes a cosmology (how the world really is and how it works), anthropological, ethical, etc. Cultural anthropologist, Clifford Geertz, pointed out that there is a dynamic relationship between what people believe about their world and their ethos: from "what is" to "how we ought to act".

In the writings of the apostle Paul, according to Troels Engberg-Pedersen (hereafter TEP), there are ideas about God and Christ and how the world is put together in time and space. These ideas TEP calls "broadly 'theological' or 'religious' and 'cosmological'. There are also ideas about how human beings relate to God, Christ and the world cosmologically understood; and ideas about how they relate to other human beings in and outside the group of Christ-believers. These ideas we may call broadly 'anthropological' and the latter group more especially 'ethical'.

So, we have:

1) Cosmology/Theology: ideas about God and how the world is.

2) Anthropology: ideas about how humans fit into the world and relate to God/Cosmos.

3) Ethics: how humans relate to each other in different contexts.

The famous German theologian, Rudolf Bultmann claimed that "every sentence [in Paul] about God is at the same time a sentence about man and vice versa ... the Pauline theology is at the same time anthropology". What he meant was that Paul's vision or "take" on cosmology/theology was profoundly influential on how he worked out how humans were to relate to God/Cosmos and each other. That is to say, if you REALLY understand how the Cosmos is/works, what IS, then it should profoundly affect how you act in all contexts, both in your relationship with the reality and your relationships within the reality.

Right here is where a very close correspondence between the Stoics, Gurdjieff, and the Cs can be noted. I'll develop some of these ideas further on, but for the moment, I'll just point out that from the Cs perspective, the ideas about densities, dimensions, higher density beings and their influence on our reality and lives, should profoundly influence how we live our lives and how we treat each other in varied contexts.

The next thing to add to the list to help clarify the issues is people's self-understanding. "Self-understanding" is a sort of formal term describing how a person thinks of themselves, how they see themselves fitting into the cosmic scheme of things. That is, is a person responsible only to themselves or only to God, or to their society; do they have free-will, is everything deterministic (no free will); and so on.

TEP: "First, Paul's construction of the self and the initial I-perspective is not at all 'individualistic' in any modern sense. And secondly... the basic thrust of Paul's writing is towards some form of communitarianism. The overarching theory to be found in Paul abut how the self should see its relationship with God, Christ, the world and the others is about a move from an I-perspective to a totally shared one. ...the whole point of his thought lies in practice. It is social practice that is his primary target."

Again, we find a striking correlation between the Stoics, Gurdjieff, and the Cs. The Stoics were focused on the "community of Sages" who acquired sufficient knowledge to move into a higher state of being; Gurdjieff makes it abundantly clear that only a GROUP can move out of the 'I-perspective'; and the Cs have been pushing "networking" as a 4th Density STO principle from the very beginning.

TEP: "First, we shall see that there is a basic similarity between Paul and the Stoics not just with regard to a number of particular, relatively minor topoi, but to a whole cluster of motifs that together constitute a major pattern of thought. That is the pattern that goes into Paul's idea of 'conversion' or 'call' understood as a change in self-understanding: a move away from an identification of the self with itself as a bodily, individual being, via an identification with something outside the self, and to a perspective shared with and also directed towards others, a perspective that will then also issue immediately in practice."

TEP then, as a modern scholar, begins to discuss how to "read Paul". He points out that "until some obstacle arises, a reader will immediately read 'eye to eye' with the author, (a) expecting to be able to understand the author, that is, to 'speak the same language as' him or her, (b) aiming in addition to understand the author's point of view as distinct from the reader's own, and (c) immediately expecting the author to express a truth - or at least what I shall call a 'real option'. ... {then quoting philosopher Bernard Williams} 'Many outlooks that human beings have had are not real options for us now. The life of a Bronze Age chief or a medieval samurai are not real options for us: there is no way of living them." By contrast, 'an outlook is a real option for a group either if it already is their outlook or if they could go over to it; and they could go over to it if they could live inside it in their actual historical circumstances and retain their hold on reality, not engage in extensive self-deception and so on."

It is here that TEP creates the divide that he believes exists between Paul's view of the world, and that of the modern human. He writes: To put it bluntly, by far most of Paul's basic world-view, in other words, the basic apocalyptic and cosmological outlook that was his, does not constitute a real option for us now - in the way in which it was understood by Paul."

And yet, it is exactly here, in his "apocalyptic and cosmological outlook" that we find a convergence between Paul and the Cs, AND Paul and scientific work that has been excluded by historians and theologians alike. I spent the entire Wave Series wandering around the idea of our world being embedded in a hyperdimensional reality, considering the possibilities of densities and other dimensions, the paranormal, etc, looking at all of it from as many angles as seemed useful, with, at the end, a positive outcome: things are NOT as they appear on the surface of our reality, and never have been.

It is also exactly in this area of apocalyptic cosmology that Paul was in accord with the Stoics and even Gurdjieff. All of them have a position on periodic cataclysms on planet Earth that "reset the system" that is closely parallel.

So, TEP considers that central parts of Paul's ideas are no longer a "real option" for the modern person to believe or consider as a Cosmology. But I take a different point of view: I think that Paul was really onto something important in a way that definitely fleshes out certain parts of what the Stoics were teaching, and is almost parallel to what the Cs say in relation to Gurdjieff's obvious Stoic background. TEP then wants to go on to extract what he can from Paul that might be still valuable by comparing it to Stoic philosophy and other ethical systems of the time, but he ignores the Stoic's own apocalyptic cosmology in the process as also no longer an option to be considered as a realistic portrayal of the Cosmos. TEP wants to compare Paul's "form of life" that was a direct outcome of his cosmology, with modern forms of life to which we do have access, to draw analogies to our own modern reality that has divested itself of any such thing as apocalypticism (in the true meaning of the word: revelation). TEP wants to salvage Paul's anthropology and ethics out of his cosmology, leaving the latter behind. He writes: '...what we present as a real option is not exactly what it is in Paul since we have cut off connections with other parts of his thought that we are not prepared to take over."

At the end of his book, "Paul and the Stoics", he writes: "We may think, indeed we should think, that Paul's belief in the story of the Christ event, in the direct form in which he understood it, was false. But we may let ourselves be stimulated by the kind of 'theologizing' that we find in Paul to think that we should ourselves adopt the same kind: one that attempts to tease out the meaning for human beings of the Christ event in a manner that makes immediate sense philosophically and in that way presents the special shape of the Christ-believing form of life as a real option to one's contemporaries."

The problem is, of course, by removing the Cosmology, TEP has essentially deprived Paul's ideas about how humans should live in relation to one another of any real, compelling justification.

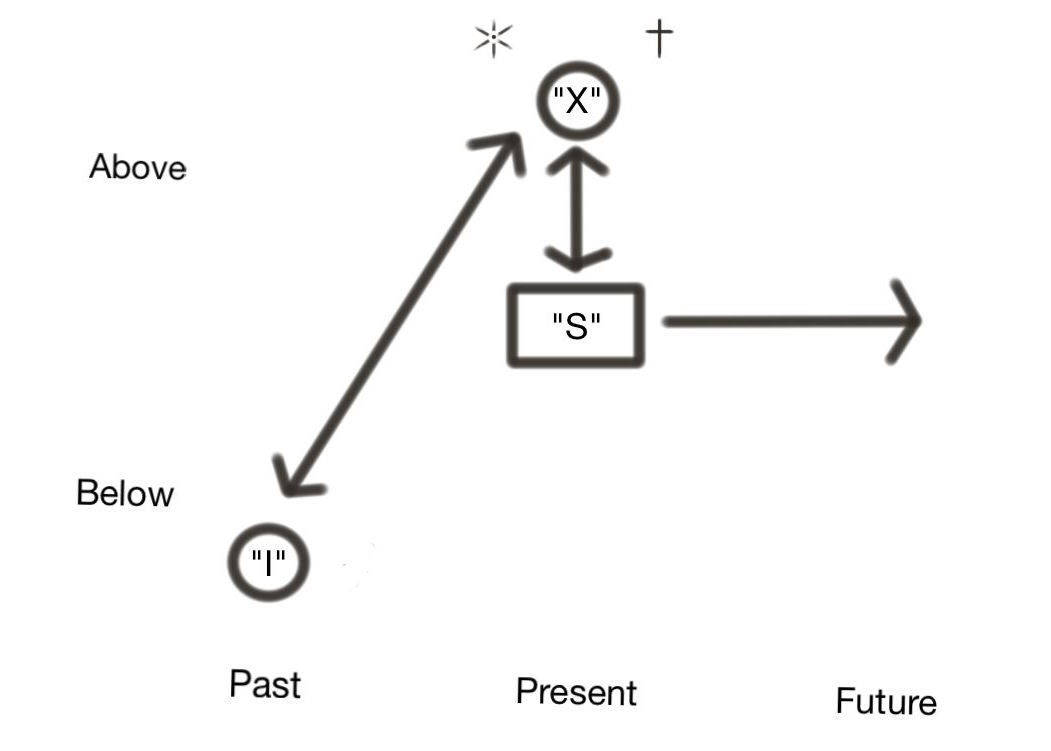

Next, I'll present the model and what it means to move from "I-centeredness" to "We-centeredness", the group, the network.

Overview of instalments in this series:

Paul and the Stoics: Introducing the Model

Paul and the Stoics: Philippians

Paul and the Stoics: Galatians

Paul and the Stoics: Romans

Paul and the Stoics: Cosmology

Q: (L) And who do we have with us this evening?

A: Frilipiaea of Cassiopaea. Good evening! You have brought two books here tonight which contain great insights. We can see the many questions in your mind. Let us answer in advance that, yes, it is true that a network can operate as suggested. Also, the model of personal transformation is exactly correct with the modifications you have devised.

Q: (L) So, in other words, I was prepared to ask all of these questions, and I had my books with me, and you just basically stole my thunder! [laughter]

(Galatea) No! They helped you. It's called helping.

A: Yes

I think it is necessary to give some background on the ideas and the model I'm going to present here. Throughout, I'll be comparing systems; however, I don't want to overwhelm the reader with more than they need at this point, so I'm going to try to keep it simple.

First, it would be helpful if the reader has read the Secret History series: "The Secret History of the World and How to Get Out Alive", "Comets and the Horns of Moses", "Earth Changes and the Human-Cosmic Connection". In "Comets", I discussed ancient Greek philosophy at some length, with particular emphasis on the Stoics.

In studying ancient religions and philosophical systems (they were often overlapping or one and the same thing in a certain sense), the main questions of modern scholars are how to categorize the different ideas that appear: are they theological, that is, the "systematic study of the divine and the exploration of religious truths", which usually includes a cosmology (how the world really is and how it works), anthropological, ethical, etc. Cultural anthropologist, Clifford Geertz, pointed out that there is a dynamic relationship between what people believe about their world and their ethos: from "what is" to "how we ought to act".

In the writings of the apostle Paul, according to Troels Engberg-Pedersen (hereafter TEP), there are ideas about God and Christ and how the world is put together in time and space. These ideas TEP calls "broadly 'theological' or 'religious' and 'cosmological'. There are also ideas about how human beings relate to God, Christ and the world cosmologically understood; and ideas about how they relate to other human beings in and outside the group of Christ-believers. These ideas we may call broadly 'anthropological' and the latter group more especially 'ethical'.

So, we have:

1) Cosmology/Theology: ideas about God and how the world is.

2) Anthropology: ideas about how humans fit into the world and relate to God/Cosmos.

3) Ethics: how humans relate to each other in different contexts.

The famous German theologian, Rudolf Bultmann claimed that "every sentence [in Paul] about God is at the same time a sentence about man and vice versa ... the Pauline theology is at the same time anthropology". What he meant was that Paul's vision or "take" on cosmology/theology was profoundly influential on how he worked out how humans were to relate to God/Cosmos and each other. That is to say, if you REALLY understand how the Cosmos is/works, what IS, then it should profoundly affect how you act in all contexts, both in your relationship with the reality and your relationships within the reality.

Right here is where a very close correspondence between the Stoics, Gurdjieff, and the Cs can be noted. I'll develop some of these ideas further on, but for the moment, I'll just point out that from the Cs perspective, the ideas about densities, dimensions, higher density beings and their influence on our reality and lives, should profoundly influence how we live our lives and how we treat each other in varied contexts.

The next thing to add to the list to help clarify the issues is people's self-understanding. "Self-understanding" is a sort of formal term describing how a person thinks of themselves, how they see themselves fitting into the cosmic scheme of things. That is, is a person responsible only to themselves or only to God, or to their society; do they have free-will, is everything deterministic (no free will); and so on.

TEP: "First, Paul's construction of the self and the initial I-perspective is not at all 'individualistic' in any modern sense. And secondly... the basic thrust of Paul's writing is towards some form of communitarianism. The overarching theory to be found in Paul abut how the self should see its relationship with God, Christ, the world and the others is about a move from an I-perspective to a totally shared one. ...the whole point of his thought lies in practice. It is social practice that is his primary target."

Again, we find a striking correlation between the Stoics, Gurdjieff, and the Cs. The Stoics were focused on the "community of Sages" who acquired sufficient knowledge to move into a higher state of being; Gurdjieff makes it abundantly clear that only a GROUP can move out of the 'I-perspective'; and the Cs have been pushing "networking" as a 4th Density STO principle from the very beginning.

TEP: "First, we shall see that there is a basic similarity between Paul and the Stoics not just with regard to a number of particular, relatively minor topoi, but to a whole cluster of motifs that together constitute a major pattern of thought. That is the pattern that goes into Paul's idea of 'conversion' or 'call' understood as a change in self-understanding: a move away from an identification of the self with itself as a bodily, individual being, via an identification with something outside the self, and to a perspective shared with and also directed towards others, a perspective that will then also issue immediately in practice."

TEP then, as a modern scholar, begins to discuss how to "read Paul". He points out that "until some obstacle arises, a reader will immediately read 'eye to eye' with the author, (a) expecting to be able to understand the author, that is, to 'speak the same language as' him or her, (b) aiming in addition to understand the author's point of view as distinct from the reader's own, and (c) immediately expecting the author to express a truth - or at least what I shall call a 'real option'. ... {then quoting philosopher Bernard Williams} 'Many outlooks that human beings have had are not real options for us now. The life of a Bronze Age chief or a medieval samurai are not real options for us: there is no way of living them." By contrast, 'an outlook is a real option for a group either if it already is their outlook or if they could go over to it; and they could go over to it if they could live inside it in their actual historical circumstances and retain their hold on reality, not engage in extensive self-deception and so on."

It is here that TEP creates the divide that he believes exists between Paul's view of the world, and that of the modern human. He writes: To put it bluntly, by far most of Paul's basic world-view, in other words, the basic apocalyptic and cosmological outlook that was his, does not constitute a real option for us now - in the way in which it was understood by Paul."

And yet, it is exactly here, in his "apocalyptic and cosmological outlook" that we find a convergence between Paul and the Cs, AND Paul and scientific work that has been excluded by historians and theologians alike. I spent the entire Wave Series wandering around the idea of our world being embedded in a hyperdimensional reality, considering the possibilities of densities and other dimensions, the paranormal, etc, looking at all of it from as many angles as seemed useful, with, at the end, a positive outcome: things are NOT as they appear on the surface of our reality, and never have been.

It is also exactly in this area of apocalyptic cosmology that Paul was in accord with the Stoics and even Gurdjieff. All of them have a position on periodic cataclysms on planet Earth that "reset the system" that is closely parallel.

So, TEP considers that central parts of Paul's ideas are no longer a "real option" for the modern person to believe or consider as a Cosmology. But I take a different point of view: I think that Paul was really onto something important in a way that definitely fleshes out certain parts of what the Stoics were teaching, and is almost parallel to what the Cs say in relation to Gurdjieff's obvious Stoic background. TEP then wants to go on to extract what he can from Paul that might be still valuable by comparing it to Stoic philosophy and other ethical systems of the time, but he ignores the Stoic's own apocalyptic cosmology in the process as also no longer an option to be considered as a realistic portrayal of the Cosmos. TEP wants to compare Paul's "form of life" that was a direct outcome of his cosmology, with modern forms of life to which we do have access, to draw analogies to our own modern reality that has divested itself of any such thing as apocalypticism (in the true meaning of the word: revelation). TEP wants to salvage Paul's anthropology and ethics out of his cosmology, leaving the latter behind. He writes: '...what we present as a real option is not exactly what it is in Paul since we have cut off connections with other parts of his thought that we are not prepared to take over."

At the end of his book, "Paul and the Stoics", he writes: "We may think, indeed we should think, that Paul's belief in the story of the Christ event, in the direct form in which he understood it, was false. But we may let ourselves be stimulated by the kind of 'theologizing' that we find in Paul to think that we should ourselves adopt the same kind: one that attempts to tease out the meaning for human beings of the Christ event in a manner that makes immediate sense philosophically and in that way presents the special shape of the Christ-believing form of life as a real option to one's contemporaries."

The problem is, of course, by removing the Cosmology, TEP has essentially deprived Paul's ideas about how humans should live in relation to one another of any real, compelling justification.

Next, I'll present the model and what it means to move from "I-centeredness" to "We-centeredness", the group, the network.

Overview of instalments in this series:

Paul and the Stoics: Introducing the Model

Paul and the Stoics: Philippians

Paul and the Stoics: Galatians

Paul and the Stoics: Romans

Paul and the Stoics: Cosmology