Natural catastrophes, according to imperial tradition, are harbingers of dynastic change. On the early morning of 28th July 1976, a giant earthquake struck Tangshan, a coal city on th Bohai Sea just over 150 kilometres east of Beijing. The scale of the devastation was enormous. At least half a million people died, although some estimates have placed the death toll at 700,000.

In the summer of 1974, seismographic experts had predicted the likelihood of a very large earthquake in the region within the next two years, but owing to the Cultural Revolution, they were hopelessly short of modern equipment and trained personnel.

Few preparations were made. Tangshan itself was a shoddily built city, with pithead structures, hoist towers and conveyor belts looming over ramshackle, one-storey houses. Below ground there was a vast network of tunnels and deep shafts. In one terrible instant, a 159-kilometre-long fault line ruptured beneath the earth, inflicting more damage than the atomic bombs dropped on either Hiroshima or Nagasaki. Asphalt streets were torn asunder and rails twisted into knots. The earth moved with such lightning speed that the sides of trees in the heart of the earthquake zone were singed. Some houses folded inwards, others were swallowed up. Roughly 95 per cent of the 11 millions square metres of living space in the city collapsed.

As soon as the tremor subsided, a freezing rain drenched dazed survivors, blanketing the city in a thick mist mingled with the dust of crumbled buildings. For an hour Tangshan remained shrouded in darkness, lit only by flashes of fire in the rubble of the crushed houses. Some survivors burned to death, but many more were asphyxiated. ‘I was breathing in the ashes of the dead,’ one victim, then a boy aged twelve, remembered.

Death was everywhere. ‘Bodies dangled out of the windows, caught as they tried to escape. An old woman lay in the street, her head pulled by flying debris. In the train station, a concrete pillar had impaled a young girl, pinning her to the wall. At the bus depot, a cook had been scalded to death by a cauldron of boiling water.’

The earthquake could not have struck at a worse moment. Beijing was paralysed by the slow death of the chairman, surrounded by doctors and nurses in Zhongnanhai. Mao felt the quake, which rattled his bed, and must have understood the message. Many buildings in the capital were shaken violently, overturning pots and vases, rattling pictures on the wall, shattering some glass windows. Many residents refused to return to their homes, sleeping on the pavements under makeshift plastic sheets until the aftershocks subsided. Instead of broadcasting the news, some neighborhood committees turned on the loudspeakers to exhort the population to ‘critisise Deng Xiaoping and carry and carry the Cultural Revolution through to the end.’ The insensitivity of the authorities to the plight of ordinary people caused widespread anger.

It was weeks before the military authorities, hampered by lack of planning, poor communication and the need to receive approval for every decision from their leaders in Beijing , responded effectively. The rescue was strategic. Tangshan was a mining powerhouse that could not be abandoned, but villagers in the surrounding countryside were left to cop alone. Officers of aid from foreign nations – search teams, helicopters, rescue equipment, blankets and food – were flatly rejected by Hua Guofeng, who used the opportunity to assert his own leadership and suggest national self-confidence. Lacking professional expertise and adequate equipment, the young soldiers relied on muscle power to pull some 16,000 people from the ruins, a fraction of those recovered earlier by the very victims themselves. The People’s Liberation Army covered tens of thousands of bodies with bleaching powder and buried them in improvised graveyards outside the city. No national day of mourning was announced. The dead were hardly acknowledged.

A few minutes past midnight on 9September 1976, the line on the monitor in Beijing went flat. It was one day after the full moon, when families traditionally gathered to count their blessings at the Mid-Autumn Festival.

Jan Wong, the foreign student who had arrived at Peking University in 1972, was cycling to class when she heard the familiar chords of the state funeral dirge on the broadcasting system. The usually strong voice of the Central Broadcasting Station was now full of sorrow, mournfully announcing the death of the Chairman. ‘We announce with the deepest grief that Comrade Mao Zedong, our esteemed and beloved great leader, passed away ten minutes after midnight.’ Other cyclists looked shocked, but not sad. In the classroom, her fellow students were dry-eyed, busy making white chrysanthemums, black armbands and paper wreaths. ‘There were no gasps of tears, just a sense of relief.’ It was a stark contrast with the outpouring of grief at the premier’s death nine months earlier.

In schools, factories and offices, people assembled to listen to the official announcement. Those who felt relief had to hide their feelings. This was the case with Jung Chang, who for a moment was numbed with sheer euphoria. All around her people wept. She had to display the correct emotion or risk ebing singled out. She buried her head in the shoulder of the woman in front of her, heaving and sniveling.

She was hardly alone in putting on a performance. Traditionally, in China, weeping for dead relatives and even throwing oneself on the ground in front of the coffin was a required demonstration of filial piety. Absence of tears was a disgrace to the family. Sometimes actors were hired to wail loudly at the funeral of important dignitaries, thus encouraging other mourners to join in without feeling embarrassed. And much as people had mastered the art of effortlessly producing proletarian anger at denunciation meetings, some knew how to cry on demand.

People showed less contrition in private. In Kunming, the provincial capital of Yunnan, liquor sold out overnight. One young woman remembered how her father invited his best friend to their home, locked the door and opened the only bottle of wine they had. The next day, they went to a public memorial service where people cried as if they were heartbroken. ‘As a little girl, I was confused by the adults’ expressions – everybody looked so sad in public, while my father was so happy the night before.

Still some people felt genuine grief, in particular those who had benefited from the Cultural Revolution. And plenty of true believers remained, especially among young people. Ai Xiaoming, a twenty-two-year-old girl eager to enter the party and contribute to socialism, was so heartbroken that she wept almost to the point of fainting.

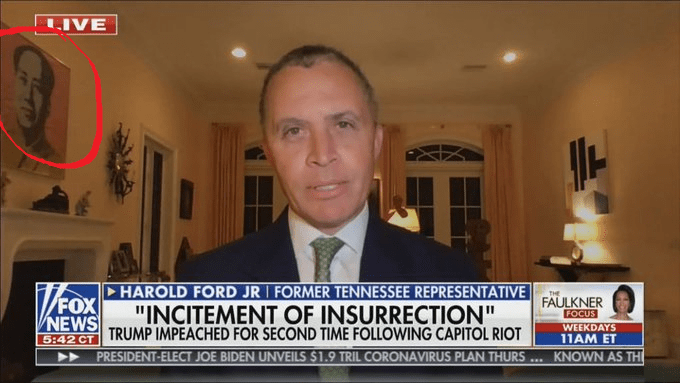

But in the countryside, it seems, few people sobbed. As one poor villager in Anhui recalled, ‘not a single person wept at the time.’ Whether or not they shed tears, by the time the state funeral was held in Tiananmen Square on 18 September, most people had collected their emotions. The entire leadership was present, with the exception of Deng Xiaoping, still under house arrest. Luo Ruiqing, one of the first leading officials tp have become a victim of the Cultural Revolution, insisted on attending the funeral in his wheelchair. He still adored the man who had persecuted him, and he cried. Hua Guofeng used the occasoion to exhort the masses to continue the campaign against Deng Xiaoping. At precisely three o’clock, he announced three minutes of silence. Silence fell over the country, as railway stations came to a standstill, buses pulled over to the side of the road, workers downed their tools, cyclists dismounted and pedestrians stopped in their tracks. Then Wang Hongwen called, ‘First bow! Second bow! Third bow!’ A million people in the square bowed three times before the giant portrait of Mao hanging from the rostrum.

It was the last public display of unity among the leaders before the big showdown. Even as the Chairman’s body was being injected with formaldehyde for preservation in a cold chamber deep beneath the capital, different factions were jockeying for power. The Gang of Four controlled the propaganda machine, and cranked up the campaign against ‘capitalist roaders’. But they had little clout within the party, and no influence over the army. They only source of authority was now dead, and public opinion was hardly on their side. With the exception of Jiang Qing, their power base was in Shanghai, a long way from the capital where all the jousting for control took place.

Most of all, they underestimated Hua Guofeng. A mere two days after Mao’s death, the premier quietly reached out to Marshal Ye Jianying, by now in charge of the Ministry of Defence. He also contacted Wang Dongxing, Mao’s former bodyguard who commanded the troops in charge of the leadership;s security. On 6 October, less than a month after the Chairman’s death, a Politburo meeting was called to discuss the fifth volume of Mao’s Selected Works. Members of the Gang of Four were arrested one by one as they arrived at the meeting hall. Madame Mao, sensing a trap, stayed away, but was arrested at her residence.

After the announcement on 14 October, firecrackers exploded all night. Stores sold out not only of liquor, but all kinds of items, including ordinary tinned food, as people splurged to celebrate the downfall of the Gang of Four. ‘Everywhere, I saw people wandering around with broad smiles and big hangovers.’ One resident recalled.

There were official celebrations too, ‘exactly the same kind of rallies as during the Cultural Revolution’. In Beijing, columns of hundreds of thousands of people waved huge banners denouncing the Gang of Four Anti-party Clique’. A mass rally was held on Tiananmen on 24 October, as the leaders made their first public appearance since the coup. Hua Guofeng, now anointed as chairman of the party, moved back and forth along the rostrum, clapping lightly to acknowledge the cheers and smiling beatifically, very much like his predecessor.

In Shanghai, posters were plastered on buildings along the Bund up to a height of several storeys. The streets were chocked with people exulting over the fall of the radicals. Nien Cheng was forced to join a parade, carrying a slogan saying ‘Down with Jiang Qing’. She abhorred it, but many demonstrators relished the opportunity, marching four abreast with banners, drums and gongs.

The political campaigns did not cease. ‘Instead of attacking Deng, we now denounced the Gang of Four.’ Madame Mao and her three fanatical followers became scapegoats, blamed for all the misfortunes of the past ten years. Some people found it difficult to separate Mao from his wife, but the strategy had its advantages. As one erstwhile believer put it, ‘It is more comfortable that way, as it is difficult to part one’s beliefs and illusions.’

Deng Xiaoping returned to power in the summer of 1977, much to Hua Guofeng’s dispointment. Chairman Hua’s portrait now hung next to that of Chairman Mao in Tiananmen Square. He slicked his hair to resemble the Great Helmsmen, and posed for staged photos, uttering vague aphorisms in the style of his former master. But while the propaganda machine churned out posters exhorting the population to ‘Most Closely Follow our Brilliant Leader’, the new chairman lacked the institutional clout and political charisma to shore up his power. His clumsy attempt at a cult of personality alienated many party veterans. His reluctance to repudiate the Cultural Revolution was out of tune with a widespread desire for change. Hua was easily outmaneuvered by Deng, who had the support of many of the older party members humiliated during the Cultural Revolution.

Ordinary people also viewed Deng as a saviour. Many of those wronged in one way or another during the Cultural Revolution pinned their hopes in the man who had survived three purges. Millions of students exiled to the countryside, most of them former Red Guards, were streaming back into the cities, worried about their future. They were joined by tens of thousands of ex-convicts, released from the gulag after suffering wrongful imprisonment during the Cultural Revolution. People from all walks of life petitioned the government for redress, from impoverished villagers who accused local leaders of rape, pillage and murder to the victims of political intrigue in the higher echelons of power. In the capital a shanty town mushroomed, as petitioners camped iutside the State Council.

Not far away, a mere kilometer to the west of Tiananmen Square, a long brick wall near an old bus station in Xidan became the focal point for popular discontent with the status quo. In October1978, a few months before an important party gathering, handwritten posters went up, attracting a huge crowd of onlookers, warmly bundled up against the cold. Some of the demonstrators demanded justice, putting up detailed accounts of their personal grievances. Others clamoured for the full rehabilitation of Deng Xiaoping and other senior officials like Peng Dehuai, purged for having stood up to Mao during the Great Leap Forward. Rumours even circulated that the vice-premier stood behind the people, having told a foreign journalist that ‘the Democracy Wall in Xidan is a good thing!’ Deng’s own slogan, ‘Seek Truth from Facts’, seemed promising. There were calls for universal suffrage, with one electrician from the Beijing Zoo named Wei JIngsheng asking for a ‘Fifth Modernisation: Democracy’, to supplement Zhou Enlai’s Four Modernisations.

Deng Xiaoping used the Democracy Wall to shore up his own position at the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee, held two months later in December 1978. Hua retained many of his titles, but Deng effectively took control of the party. It was Deng who went to the United States in February 1979, thrilling the American public when he donned a cowboy hat at a rodeo in Texas. He circled the arena in a horse-drawn stagecoach, waving to the crowd, and generally charmed business leaders and politicians during his stay.

When Deng returned home, he found growing unrest. The Democracy Wall had been transformed into a hotbed of dissent, as several demonstrators led by a construction worker who had been raped by a party secretary organised a protest march through Tiananmen Square on the anniversary of Zhou Enlai’s death. They were arrested, but their daring opposition to the communist party inspired others. In a poster entitled ‘Democracy of New Dictatorship’, Wei Jingsheng branded Deng Xiaoping a ‘Fascist dictator’.

There was to be no democracy, and Wei Jingsheng was rounded up together with dozens of other dissidents, some to be imprisoned for twenty years. As one disillusioned observer put it, ‘The old guard reverted to the old way of managing the country.’ A year later, Peng Zhen, the mayor of Beijing who had been one of the first targets of the Cultural Revolution, moved to eliminate once again four basic rights codified into the constitution after the death of Mao. The rights of citizens to ‘speak out freely, air their views fully, engage in great debates and write big-character posters’, heralded by the Chairman in 1966, were blamed for having contributed to the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. The right to strike was abolished a year later.

Still every dictator has to differentiate himself from his predecessor, and Deng was keen to draw a line under the Cultural Revolution. Since roughly half of all members had joined the communist party since 1966, and most of the old guard had at one point or another been trained by the sordid politics of the Cultural Revolution, a systematic attempt to call perpetrators to account would have led to a gigantic purge. There were many rehabilitations, but very few prosecutions. Liu Shaoqi, together with all his followers, was formally exonerated in February 1980.

The most politically expeditious way of assigning blame without implicating either the communist party or the founding father of the regime was to put the Gang of Four on trial. In November 1980, Jiang Qiong, Zhang Chunqiao, Wang Hongwen and Yao Wenyuan entered a courtroom at Justice Road near Tiananmen Square, accused of masterminding a decade of murderous chaos. Madame Mao was defiant, hurling abuse at her accusers. At one point she quipped that ‘I was Chairman Mao’s dog. I bit whomever he asked me to bite.’ Behind the scenes, a special team headed by Peng Zhen orchestrated the show trial. Jiang Qing and Zhang Chunqiao were given the death penalty, commuted to life imprisonment. Ten years later, in 1991, Jiang Qing hanged herself inside her cell with a rope made her own socks and a few handkerchiefs. Wang Hongwen died in prison the following year. But Yao Wenyuan and Zhang Chunqiao were released after serving twenty years, living out their lives under tight police surveillance.

Other prominent members of the Cultural Revolution Group were also condemned, including Chen Boda. The Chairman had already placed him behind bars in 1970, and he would not be released until 1988.

Lacking any independent legal system, party officials at every level decided who would be punished and who would not. ‘Some rebels were rightly punished. Some got rough justice. Others were let off lightly.’

In July 1981, to mark its sixtieth birthday, the party issued a formal resolution on its own history. The document barely mentioned Mao’s Great Famine and blamed Lin Biao and the Gang of Four for the Cultural Revolution, while largely absolving the Chairman. Mao’s own verdict on the Cultural Revolution was used by Deng to evaluate the entire role of the Chairman in the history of the communist party. It was exactly the same assessment that Mao had given of Stalin, namely 70 per cent successful and 30 per cent a failure.

The revolution was designed to terminate all public debate about the party’s own past. Academic research on major issues such as the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution was strongly discouraged, and any interpretation that strayed from the official version was viewed with an unsympathetic eye.

But the document also had other goals, more closely linked to current politics than to past history. Deng Xiaoping used the resolution to criticise Hua Guofeng and establish his own credentials as paramount leader. The reign of Chairman Hua was lumped together with the Cultural Revolution, while the Third Plenum in December 1978 was consecrated as the ‘Great Turning Point in History’, when under the guidance of Deng Xiaoping the party finally embarked on the ‘correct path for socialist modernisation’.

The path involved a programme based onZhou Enlai’s Four Modernisations. Its most remarkable feature was how reluctantly economic reforms were introduced. By 1976, much of the country was reeling from three decades of economic mismanagement and years of political chaos. The third Plenum was not so much a ‘Great Turning Point in History’ as an attempt to restore the planned economy to its pre-Cultural Revolution days. Deng Xiaoping and his acolytes were looking back, not forward. In agricultural policy, they revived the various measures taken in 1962 to protect the countryside from the radical collectivisation that had run amok during the Great Leap Forward. Small private plots were once again allowed, but the leadership explicitly prohibited dividing the land. In April 1979 it even demanded that villagers who had left the collectives rejoin the people’s communes. But it did make one concession: three years after Mao’s death, the party finally increased by 20 per cent the price of the grain compulsorily to the state. The prices changed for agricultural machinery, fertilisers and pesticides were also reduced by 10 to 15 per cent.

Real change was driven from below. In a silent revolution dating back at least a decade, cadres and villagers had started pulling themselves out of poverty by reconnecting with the past. In parts of the countryside they covertly rented out land, established black markets and ran underground factories. The extent and depth of these liberal practices are difficult to gauge, as so much was done on the sly, but they thrived even more after the death of Mao. By 1979, many county leaders in Anhui had no choice but to allow families to cultivate the land. As one local leader put it, ‘Household contracting was like an irresistible wave, spontaneously topping the limits we had placed, and it could not be suppressed or turned around.’ In Sichuan, too, local leaders found it difficult to contain the division of the land. Zhao Ziyang, who had arrived in Sichuan in 1975 to take over as the head of the provincial party committee, decided to go with the flow.

By 1980, tens of thousands of local decisions had placed 40 pre cent of Anhui production teams, 50 per cent of Guizhou teams and 60 per cent of Gansu teams under household contracts. Deng Xiaoping had neither the will nor the ability to fight the trend. As Kate Zhou has written, ‘When the government lifted restrictions, it did so only in recognition of the fact that the sea of unorganised farmers had already made them irrelevant.

In the winter of 1982-3, the people’s communes were officially dissolved. It was the end of an era. The covert practices that had spread across the countryside in the last years of the Cultural Revolution now flourished, as villagers returned to family farming, cultivated crops that could be sold for a profit on the market, established privately owned shops or went to the cities to work in factories. Rural decollectivisation, in turn, liberated even more labour in the countryside, fueling a boom in village enterprises. Rual industry provided most of the country’s double-digit growth, offsetting the inefficient performance of state-owned enterprises. In this great transformation, the villagers took centre stage. Rapid economic growth did not start in the cities with a trickle-down effect to the countryside, but flowed instead from the rural to the urban sector. The private entrepreneurs who transformed the economy were millions upon millions of ordinary villagers, who effectively out-maneuvered the state. If there was a great architect of economic reform, it was the people.

Deng Xiaoping used economic growth to consolidate the communist party and maintain its iron grip on power. But it came at a cost. Not only did the majority of people in the countryside push for greater economic opportunities, but they also escaped from the ideological shackles imposed by decades of Maoism. The Cultural Revolution in effect destroyed the remnants of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong thought. Endless campaigns of thought reform produced widespread resistance even among party members themselves. The very ideology of the party was gone, and its legitimacy lay in tatters. The leaders lived in fear of their own people, constantly having to suppress their political aspirations. In June 1989, Deng personally ordered a military crackdown on pre-democracy demonstrations in Beijing, as tanks rolled into Tiananmen Square. The massacre was a display of brutal force and steely resolve, designed to send a signal that still pulsates to this day: do not query the monopoly of the one-party state.