And again, it took me longer than expected, since I don't prioritize this project. But I made a few more, on more details about how complex language is. It may be a bit more “nerdy”, but hopefully it explains some things about language that you may never have thought about. You’re a genius for speaking any language!

If you are a language nerd, you will like this one! How many parts of our bodies do we need to produce speech? Which is the only floating bone in our body, and how is it useful for speech? How do we use statistics all day long when producing language, and not even realizing it? What is Theory of Mind? What abilities do we need to put to use every time we speak, ranging from motor skills, to cognitive abilities and social aptitudes? All this and much more, to explain how everything in language is complex, and how its basic dictionary definition doesn’t even begin to explain it.

TRANSCRIPT:

"Hello! And welcome to Language with Chu.

Today we’re going to talk about something very simple, actually. Yet, I hope to show you that it’s a lot more complicated than it seems. If you’ve watched my previous videos about Sounds and Meaning, and about Language Complexity you already have an idea of where I’m trying to get to.

But I’ll start with the simplest question of them all: What is Language? And by working on that definition I hope that it’s not too nerdy and that you get a lot of ideas about how language works, and why the state of Linguistics, or the state of the “science of language” is kind of stagnant nowadays.

One of the problems is that, like in any science, most people try to find a very simple definition for something, so that the hypotheses that they are testing will make sense, will be able to be tested even, and the experiments replicated, etc. Well, Linguistics is a little bit in between, because it’s within the Humanities, but some currents of Linguistics have been trying for decades to make it more scientific.

So it’s a little bit between both sides, and you can forgive some linguists for being too “scientific” and missing the forest for the trees, or some others for being too “wishy-washy” in their definitions. But the problem is that, with language, I think, you can’t just focus on one simple definition. In fact, I hope that in the examples that come next, you’ll see that everything in language is complex, and everything in language requires more than one dictionary definition.

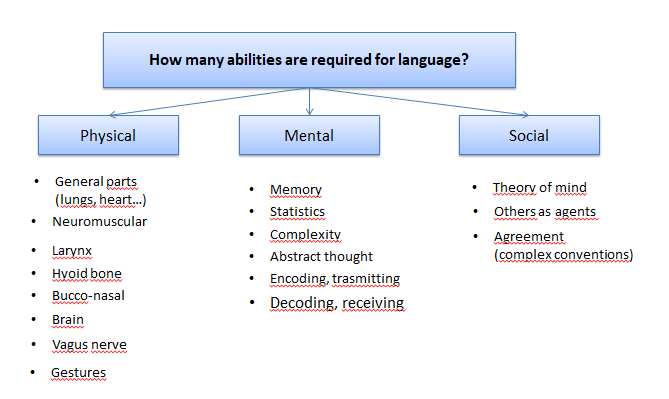

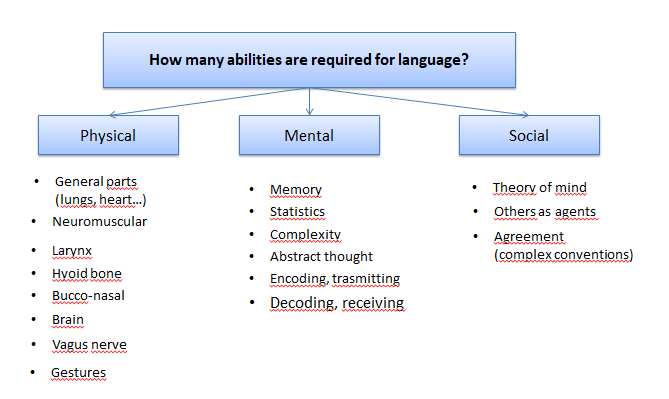

Ok, so, let’s start with “What is Language?”. If I were to ask you how many abilities you need to speak, and to use language in general… And here, just a note: When I’m talking about “Language”, I’m talking about the Language capacity, not each individual language, ok? So, what do we need to know from a physical point of view, from a mental or cognitive point of view, and from a social point of view? What is the set of skills that you need in order to speak? And I would suggest that you pause the video here, and think about it. Make you own little bullet points, and then resume watching, and see if you got them all. I probably missed many, but I think you’re going to be surprised. [Pause].

Okay, I’m assuming you paused the video and did that little exercise if you felt like it, but let’s start with the physical things that you need to have and to know: First of all, you have to

have “parts” that work. You need to have lungs to breathe, you need to have a heart… If you’re not alive you’re not going to be talking! You need a functioning brain… You need everything that makes you a human being to talk.

That’s number one, and they need to work FOR language. For example, our breath is used in a specific way to materialize language. Otherwise you could just be breathing without making any noises, any vocalizations, and it wouldn’t be called “speech”.

Second, you need

a neuromuscular complex, I would say: we have roughly 700 muscles in our bodies, and about 78 of them are muscles that we use for speech. Not just for speech, but mainly for it. So, that’s a lot! And you need every tiny muscle and nerve and everything to help you articulate the sounds you make (produce sound), they need to help you control how you articulate things (otherwise nobody could understand you), and they have to make it as easy as possible for you to produce sounds.

So all of that is an entire mechanism working in the background while you use speech. You have a lot of skills you don’t even realize you have, because they are subconscious [automatic], basically.

Then you need the

larynx, and the larynx is basically the “voice box” that we have (some people call it the voice box), but it’s just 2 inches long, it’s not very big. And without it, we couldn’t speak either. But the interesting thing is that it’s involved in many functions apart from language. And you’ll see this more, and more, and more. There is hardly any unique thing that we could say, “this is ONLY for language”. For example, we use the larynx, all this part of our necks to swallow, to breathe, to cough… and there are minute mechanisms going on in the larynx to allow you to talk, or to swallow, not to choke, etc. So you need the larynx.

You also need something called the

hyoid bone. I don’t know if you’ve heard of it. But it’s this floating little bone, kind of inside here… You cannot really palpate it, but it’s studied nowadays for problems with sleep apnea. It’s used in forensics for determining of somebody was strangled or not. And as a funny piece of trivia, I’ll let you that if anybody asks you, “which is the only bone in the body that floats?”, you can say it’s the hyoid bone. It’s not quite correct, because it’s floating on air, but it’s a bit like the patella, the knee cap. But this one is particularly… Here in the image you can see how it really looks like it’s floating. It’s connected by a bunch of ligaments and little muscles and stuff, but it doesn’t articulate with any other bone. So that’s why it is said to be floating.

Well, this little bone is interesting because it is in the right position to help the tongue move, to help the larynx open and close so that you can speak, or swallow or eat….

And animals have it… animals have a larynx too (many animals), but they don’t have them in the right position to allow for speech. It’s commonly believed that one of the things that made humans speak [in the course of evolution] was the descent of the larynx. In some animals it’s very, very high, so it doesn’t allow for the cavities that we have. Resonance cavities and such. And there is not much difference between the sounds that they can produce for vocalization, and the piping for eating or breathing. In our case, humans, our larynx is quite low and that creates enough room, levers and pulleys that allow us to do both: breathe and eat, and speak. But, I can tell you right now that that’s not really true, because many animals also have a lowered larynx, and it’s not because of that that they speak. So, it can’t be the only factor. None of these are the only factors, but they all contribute to speech.

You also need

a bucco-nasal cavity. So, anything that resonates, from your nose, to your cheeks, to everything in your mouth, your teeth, etc. In my videos about phonemes and sounds I described how each sound in language is placed in the mouth, and they each have their names, etc. If you are interested, check that video too.

And then you have

a brain. Obviously, you need to have a functioning brain. And again, there is so little that is known about it! You will hear that Broca’s area, or Wernicke’s area is for language. And although there is some specialization and language is mostly seated on the left hemisphere, there are many cases of injuries where the brain immediately kind of takes over, or compensates for the part that is injured and uses something else.

So, I don’t think it’s as simple as saying, “Here is my language center”, or whatever. Not to mention that, as we’ll see in a minute, we need so many skills to speak and to use language, that it seems that the whole of the brain is lighting up when we speak. Also, the studies that we CAN do nowadays, with brain scans and MRIs… They are quite limited, if you think about it, because all they are showing is brain activity as in electricity, and maybe some neurochemicals acting, and chemical activity. But it’s not the whole banana, because where is it all stored? How does it work? The amount of words you know, the amount of knowledge you have about the world…

I had an MRI done once, and my brain looked quite tiny, you know? And I speak three languages really well, and three others not so well, and I have no idea of how it could all fit into my small brain. Maybe you have a bigger brain!

Anyway, I don’t think that explains language and how it works. I think it has more to do with the connection between brain and mind, so everything that is non tangible but that is usually equated with the brain.

Okay, and finally (I’ll go through these quickly), you need the

vagus nerve. I’ve spoken about the vagus nerve in previous videos too. What is interesting is that, as I just said, the brain is not everything, and the vagus nerve, not only does it have the right branch that controls, or helps you regulate a lot of your facial movements, but it also has a very important pro-social role. And also, it reaches all the way down to your gut. Recently, or not so recently, scientists found out that 90% of the branches of the vagus nerve send signals up to the brain. And do you know what also is in the gut? Neurons. There are a lot of neurons. So again, nobody knows how we think, how we feel. Maybe most of the time we’re thinking with our guts? I don’t know. Anyway, you need that to speak as well.

And you also need

gestures. For many linguists, gestures are at the beginning of the emergence of language. I don’t quite agree, and if you’ve watched the previous videos in this series, you know why. But gestures (gesticulating) is important for language, and the more you know who to use them, the more you can use them, the better for language.

OK? So that’s it for what you need to do physically, and if you notice, all of this is almost subconscious, or you don’t really have a lot of control over it. You’re not thinking, “I have 78 muscles in my face that are helping me produce language”, right? If you think about it, you might say so, but most of the time we use language spontaneously, without giving any of these things a thought. OK? So, I would say that this is part of the definition of language if you include what is required for language.

Next we have anything that is cognitive. So, what do we need in our brains or our minds to use language? Well, you need

memory. And memory of several kinds. You need short-term memory. Because, say you forget everything I say 3 seconds after I’ve said it. You wouldn’t be able to watch anything, to listen to anybody, you wouldn’t be able to keep your train of thought, etc. You need long-term memory to remember all kinds of things about the environment, about the social situations, about a text, for example… Everything in your long-term memory helps you understand language, more so than we often think it does.

Then you need something kind of nifty, which is

statistics. And we are all kind of experts at statistics, if you think about it, because when you learn a language, there are things that are allowed, and not allowed. When you listen to a foreign language, there are sounds that just don’t sound English to you, right? Why? Because you are doing all kinds of computations in your head that tell you, okay, these sounds are normal/allowed in English.

Not only that, but these sounds can also be combined in a specific order in different ways, and when you shuffle them around, they just don’t sound English anymore, right? Well, all those things are a kind of statistic work, because you are always working on probabilities. When you listen to somebody, your brain is calculating, “Does that make sense? Is this more likely than not?” And if it is more likely, then I can even not hear the sounds, and make up the word: If I tell you, “I like ‘omputers”, you didn’t hear the “c”, and maybe you didn’t even notice you weren’t hearing the “c”. “I like ‘omputers”. And you kind of made it up, because you know that, statistically, “omputer” is usually preceded by a /k/ sound.

OK, and that shows that there is a HUGE amount of

complexity in what we say. We use language all the time, and it’s so easy, or it sounds so easy to us… It’s only when we meet somebody who is learning our language, our mother tongue as a foreign language that we realize how hard it is. And we don’t even realize all the knowledge we have.

For example, if you are a native speaker of English, could you conjugate the copula in the third person plural, simple past? I’d be interested in hearing how many of you did it, if you can post a comment. What I just said may have sounded like Chinese, but it’s just “they were”, as in “they were happy”. The verb “to be” is called the copula in linguistic jargon.

Or if I tell you the verb…. Give me the verb “to look” in the second person singular, in the present perfect. Can you do it? “He has looked”, or “She has looked”, or “It has looked”. So, see? I know that because I learned English as a second language, but you don’t need to know that. You have all these rules… phonological rules, morphological rules (so which word chunks can go together with which ones)… you know all the verb tenses, you know how to put sentences together… All those things, you have no idea how you do it, but you know it. And when some “annoying” foreigner starts asking you, “but why did you use this tense instead of that other one, blahblah”, you go like, “I don’t know, I just use it!”. So, there is a lot of complexity in what is going on in your mind.

You also need

abstract thought, obviously, because not everything is concrete. You need abstract thought even for having a conception of time when you are speaking. You need abstract thought for everything, basically when you speak. It would be very hard to only focus on concrete thoughts to be able to have the type of communication we have nowadays.

And then you need a whole apparatus

of encoding and transmitting: so, I’m encoding information and sending it to you; you’re

decoding it and receiving all the information. Nobody really knows how that works. There is Information Theory based on some of these concepts, but from there to know how it works in the brain… Scientists have tried, and keep trying to find out how it all works, but like I said, there is so much that we have inside our brains, that it is very difficult to know why, and how language really happens.

OK, and then finally, from a social point of view, you need something that is quite human, although some animals have it to a certain extent too. And that is “

theory of mind“. And “theory of mind” is just a term for describing when you can ascribe a mental state to somebody, and predict their reactions, and adjust your own behavior. So, say I tell you, “Hi! How are you?”, and you say, “I’m okay…” [with a sad face]. I already know from your expression that you are not really doing ok. So I can’t take you literally, and I may as you, “What’s wrong?”. Or when I’m about to make a request, if I’m a little nervous I may be trying to figure out first if you are in a good mood, if you’re not, etc. So, all those things are “theory of mind”, and in language it’s super important because we read a lot of non-verbal cues, sometimes more so than words.

Then, there is something that goes with it: we also have to take

other people as agents. If you imaging that people are talking for the sake of talking (some people do, but…!

But if you imagine that nobody has anything to say, then you wouldn’t try to find meaning in a sentence. And because we see that each person is an agent of communication, we try to find meaning, we try to express meaning, we try to be clear, etc.

And finally, we have to agree tacitly, and also subconsciously many times, to a HUGE amount of

conventions in language. You have like a whole rule book inside your head that tells you “This comes after this”, or if a person says “hello”, I respond, etc. You know that if I tell you, again, “How are you?”, and you tell me “The sky is blue”, I’m going to think that there is something wrong with you, right? It’s completely out of context. So, there are all kinds of social norms. In some languages it’s even more important when there are different personal pronouns, for example, depending on the social rank of the person, or the age, like in Japanese.

And all those things, you are doing within a millisecond. You are processing A LOT of information. All of this, basically, that you see on the screen, is working at the same time, every time you say anything. Practically anything.

And what is interesting is that, like I said on previous videos, these parts weren’t really designed FOR language, or don’t seem to have been designed for language. Because if you take any of those physical, and mental, and social traits or abilities, you could say that they are part of a much bigger cognitive complex, or you could say that they are part of a much bigger network of functions that we fulfil as human beings. And each of the little parts, physical or not, allow you to do a multitude of things, not just speaking. So that’s a bit puzzling when you are talking about

evolution, because, well, which one came first, if we need them all at once?

Then, from a more cognitive point of view, language is

integral to our lives, I think. There are cases of children who were born and left in the jungle, or from sadistic parents who left them locked up in an attic, for example, until they were teenagers and they were found. And you can see in those children that they actually don’t have, not just language, but they’re also missing a lot of other cognitive and social abilities that your average Joe has. So, I think that language has a lot to do with our general development. It’s not just a system of communication, as it is normally described.

And then finally, an interesting bit about language is that it is completely

blind do demographics, to social status, to anything. You can speak differently, but every human being (except for exceptional circumstances like I said before)… every single human being has at least one language. In fact, monolinguals (just one language) are a minority in the world. Most people can learn 2, 3 or 5 language with no problem, from birth.

So that’s it for the abilities required in language. I hope it’s not too “nerdy”, as I said, but just think about how smart you are if you ever are in doubt, for being able to do all those things at once.

And here you can see why there is a debate between the camp that says that we are born with it all, because it’s so complex that we could never have learned that in such a short amount of time when we were children; and the others that say that we learn it all. That obviously we were born with a certain ability for speaking, but that learning has a lot to do with it. And well, the two camps sort of fight with each other. I think both of them are right, and both of them are wrong in that they limit their definitions.

We will hopefully talk about that in more detail later. But yes, we’re born with a certain capacity for language, for sure. And our environment is very important. But just saying that you were born with it doesn’t mean that it’s all in your brain or your genes. In fact, there hasn’t been a lot of progress made in that respect. And just because you say it’s social and it’s learned, it doesn’t mean that it’s only the caregivers that teach language to a child that will have the only say in how it’s done, or that will provide the biggest amount of input. I think it’s a lot more complex than that.

This is just the first slide, so I talked a lot, I think! But anyway, I hope you liked it. We’ll stop here for this “episode”, and we’ll move onto language functions next. So, what does language do? And the types of knowledge that you need to have. Hopefully then to move into these kinds of myths that exist around linguistics and around the idea of language, and which ones we can rescue, and which ones should really be tweaked a bit so that they match reality, finally.

OK, so let me know in the comments if you thought of other abilities that are required for language, if I missed any important ones (I was just trying to summarize), and if YOU think that language is innate, or if we learn it. See you next time."

Otherwise I stake months to do the next one, LOL! At this rate, I have to try and be more regular, or the channel won't grow at all. I think of lots of things to say, and then, I chicken out a bit, or start thinking that I need to know a lot more before sharing, etc. But then I remember that one can find all sorts of videos on Youtube, and that I don't need to have a full thesis approved by Standford University before sharing.

Otherwise I stake months to do the next one, LOL! At this rate, I have to try and be more regular, or the channel won't grow at all. I think of lots of things to say, and then, I chicken out a bit, or start thinking that I need to know a lot more before sharing, etc. But then I remember that one can find all sorts of videos on Youtube, and that I don't need to have a full thesis approved by Standford University before sharing.