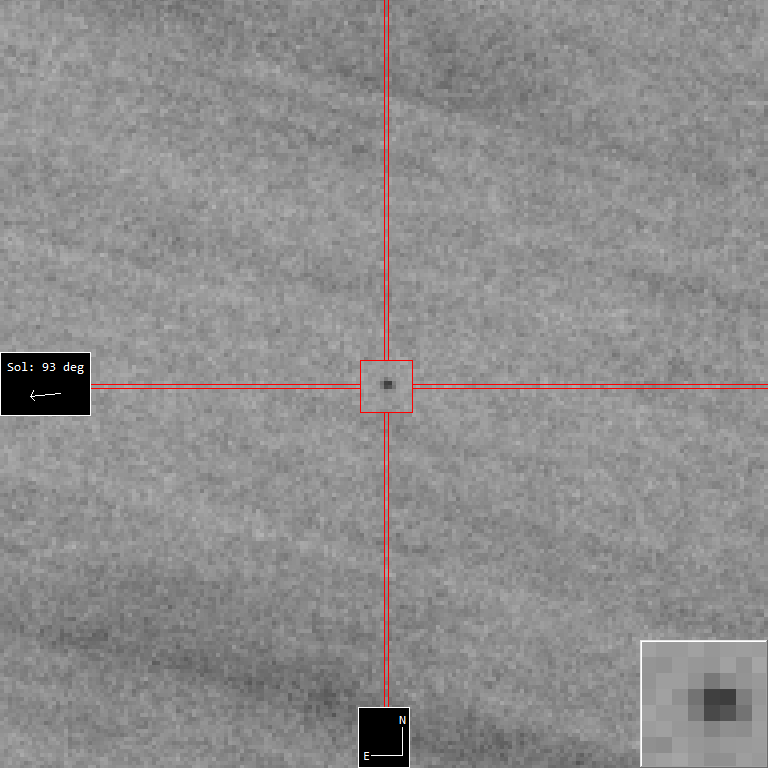

The locations of 115 candidate free floating planets in the region between Upper Scorpius and Ophiuchus (

(Image credit: European Southern Observatory, CC BY-SA)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Joanna Barstow, Ernest Rutherford Fellow, The Open University

We now know of almost 5,000 planets outside the solar system. If you were to picture what it would be like on one of these distant worlds, or

exoplanets, your mental image would probably include a parent star — or more than one, especially if you're a "Star Wars" fan.

But scientists have

recently discovered that more planets than we thought are floating through space all by themselves — unlit by a friendly stellar companion. These are icy "free-floating planets," or FFPs. But how did they end up all on their own and what can they tell us about how such planets form?

Related:

The 10 biggest exoplanet discoveries of 2021

Finding more and more exoplanets to study has, as we might have expected, widened our understanding of what a planet is. In particular, the line between planets and "

brown dwarfs" — cool stars that can't fuse hydrogen like other stars — has become increasingly blurred. What dictates whether an object is a planet or a brown dwarf has long been

the subject of debate — is it a question of mass? Do objects cease to be planets if they are undergoing nuclear fusion? Or is the way in which the object was formed most important?

While about half of

stars and brown dwarfs exist in isolation, with the rest in multiple star systems, we typically think of planets as subordinate objects in orbit around a star. More recently, however, improvements in telescope technology have enabled us to see smaller and cooler isolated objects in space, including FFPs — objects that have too low a mass or temperature to be considered brown dwarfs.

What we still don't know is exactly how these objects formed. Stars and brown dwarfs form when a region of dust and gas in space starts to fall in on itself. This region becomes denser, so more and more material falls onto it (due to

gravity) in a process dubbed gravitational collapse.

Eventually this ball of gas becomes dense and hot enough for nuclear fusion to start — hydrogen burning in the case of stars, deuterium (a type of hydrogen with an additional particle, a neutron, in the nucleus) burning for brown dwarfs. FFPs may form in the same way, but just never get big enough for fusion to start. It's also possible such a planet could start off life in orbit around a star, but at some point get kicked out into interstellar space.

The different characteristics of free floating planets, brown dwarfs and low mass stars. 13 Jupiter masses is often used to distinguish planets from brown dwarfs. Please note that size and mass are different entities — brown dwarfs are roughly the size of Jupiter although more massive. (Image credit: Joanna Barstow)

How to spot a wandering planet

Rogue planets are difficult to spot because they are relatively small and cold. Their only source of internal heat is the remaining energy left over from the collapse that resulted in their formation. The smaller the planet, the quicker that heat will be radiated away.

Cold objects in space emit less light, and the light they do emit is redder. A star like the

sun has its peak emission in the visible range; the peak for an FFP is instead in the infrared. Because it's challenging to see them directly, many such planets have been found using the indirect method of "gravitational microlensing," when a distant star is in just the right position for its light to be gravitationally distorted by the FFP.

Read more:

Rogue planets: hunting the galaxy's most mysterious worlds

However, detecting planets via a single, unique event comes with the disadvantage that we can't ever observe that planet again. We also don't see the planet in context with its surroundings, so we’re missing some vital information.

To observe FFPs directly, the best strategy is to catch them while they are young. That means there is still a reasonable amount of heat left over from their formation, so they are at their brightest. In the recent study, researchers did just that.

The team combined images from a large number of telescopes in order to find the faintest objects within a group of young stars, in a region called

Upper Scorpius.

They used data from large, general purpose surveys combined with more recent observations of their own to generate detailed visible and infrared maps of the area of sky covering a 20-year period. They then looked for faint objects moving in a way that indicated they were members of the group of stars (rather than background stars much further away).

The group found between 70 and 170 FFPs in the Upper Scorpius region, making their sample the largest directly identified so far — though the number has significant uncertainty.

Rejected planets

Based on our current understanding of gravitational collapse, there seems to be too many FFPs in this group of stars for them all to have formed in that way. The study authors conclude that at least 10% of them must have started out life as part of a star system,

forming in a disk of dust and dust around a young star rather than through gravitational collapse. At some point, however, a planet could get ejected due to interactions with other planets. In fact, the authors suggest that these "rejected" planets may be just as common as planets that have been alone from the beginning.

If you're panicking about Earth suddenly spinning off into the depths of space, you probably don't need to worry — these events are far more likely early on in the formation of a planetary system when there are a lot of planets jostling for position. But it's not impossible — if something external to an established planetary system,

such as another star, were to disrupt it, then a planet could still be detached from its sunny home.

While we still have a long way to go to fully understand these wandering planets, studies like this one are valuable. The planets can be revisited for further, more detailed investigation as new telescope technology becomes available, which might reveal more about the origins of these strange worlds.

This article is republished from

The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the

original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

![The Torino scale is a simplified version of the Palermo scale, used as a communication tool to illustrate the impact hazard of asteroids from a combination of their probability of impact and the energy they could strike with.] The Torino scale is a simplified version of the Palermo scale, used as a communication tool to illustrate the impact hazard of asteroids from a combination of their probability of impact and the energy they could strike with.]](/forum/proxy.php?image=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.esa.int%2Fvar%2Fesa%2Fstorage%2Fimages%2Fesa_multimedia%2Fimages%2F2007%2F12%2Fthe_torino_scale_used_to_quantify_the_impact_hazard_of_a_certain_neo%2F9804503-3-eng-GB%2FThe_Torino_Scale_used_to_quantify_the_impact_hazard_of_a_certain_NEO_article.jpg&hash=0a000a2bc898528f9b36b808febb78b1)