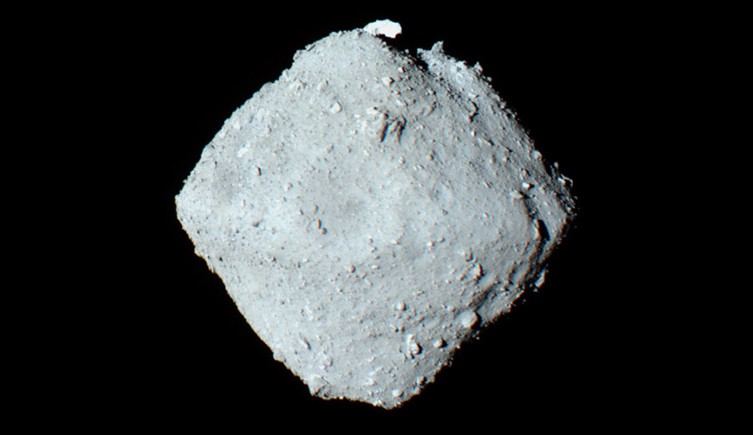

A tiny sample of the Ryugu asteroid collected by the Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa2 indicates the asteroid formed right when the solar system was being born some 4.5 billion years ago.

This material is some of the most pristine rock ever studied and will hopefully give scientists a glimpse into the origin of life.

Initial analyses of the samples collected from the asteroid Ryugu indicate that it is some of the most pristine matter in the entire solar system.

The piece was collected when the

Japanese space mission Hayabusa2 briefly touched down on the near-Earth asteroid Ryugu to sample its surface. Once the mission returned to Earth, scientists began eagerly studying its precious cargo to see what the sample could reveal.

They discovered that the asteroid's chemical composition is incredibly similar to that of the Sun, and that it formed just five million years after the solar system came into existence. The information that is being gleamed from this tiny sample will help us to better understand the origin not only of the planets and stars but also of life itself.

Professor Sara Russell is a planetary science researcher at the Museum who specialises in the formation of the solar system. She was involved with this new paper, which was published in the journal

Science.

'Looking at the chemistry of Ryugu, it looks very much like the elementary composition of the Sun,' explains Sara. 'If you were to take away the hydrogen and helium from the Sun, you'd have this bunch of other elements, and they are in about the same proportion as what we see in the Ryugu sample.'

'What this means is that Ryugu represents very primordial material from which the whole solar system was made - it is kind of the ancestral material. This exceeded our wildest dreams.'

The spacecraft Hayabusa2 launched in 2014 and didn't arrive at Ryugu until 2018. ©JAXA

Sampling an asteroid

In December 2014 the

Japanese space agency JAXA launched their spacecraft Hayabusa2 with the aim of traveling across the solar system and making contact with the asteroid Ryugu.

Reaching the asteroid in 2018, the plan was to

land several rovers onto its surface and to collect not only surface material but also sub-surface samples of rock. This was achieved by firing a tiny pellet at the asteroid, before flying in to collect the fragments of rock and soil that were dislodged.

After six years and travelling some five billion kilometres, the

spacecraft returned to Earth in December 2020 and released a capsule, containing these important samples, above Woomera in South Australia.

This material has formed the basis of an international quest to test, study and analyse every aspect of the asteroid in order to better understand exactly how it formed and what secrets it might hold.

'Hayabusa2 collected about five grams of material, which might not sound like very much, but it is loads,' says Sara. 'It is actually more than JAXA were expecting and more than an order of magnitude than Hayabusa1 - their first asteroid return mission.'

This first paper looking into the properties of the material sampled is focusing on its chemistry, whilst subsequent studies will be delving into its mineralogy and petrology.

A deep dive into an asteroid

This initial work has shown that the chemical makeup of the asteroid is incredibly ancient and far more pristine than anything seen before.

'Before the Ryugu sample came back, we thought we had the most-primitive material in the solar system, a type of meteorite called CI-chondrites,' explains Sara. 'At the Museum we actually have the type specimen of this meteorite, called Ivuna.'

'When comparing the Ryugu sample to Ivuna, the material actually looks very similar. But the bottom line is that Ryugu is even more unaltered than Ivuna.'

It was thought that Ivuna was the most pristine material in the solar system until Hayabusa2 brought its sample back. ©The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

This is because, by comparing the two samples, researchers can now see that when Ivuna travelled through Earth's atmosphere and landed on the planet's surface, it absorbed liquid water. This had the effect of subtly altering the chemistry of the meteorite.

'The Ryugu sample, however, is super pristine,' says Sara. 'That is one of the reasons why sample return missions have an advantage over meteorites because the sample has never been exposed to Earth's atmosphere and has been kept in very careful curatorial conditions.'

The pristine nature of the Ryugu sample is also related to the fact that the asteroid has never experienced temperatures above 100°C. This is significant because scientists believe that the building blocks of life itself - compounds such as amino acids - were originally brought to Earth by asteroids.

If the asteroid had been heated to temperatures exceeding 100°C, then these compounds would have effectively been boiled off the surface and lost to space.

The way in which Ryugu formed means that while chemically the asteroid is very primitive, it is difficult to say whether the sample represents the exact starting material from which the planets in the solar system were built. This is because, as the asteroid was forming, it gathered ice particles within the grit and pebbles, which subsequently melted over time. This water then turned the rock into clay, which is what it has stayed as ever since.

This research is just scratching the surface of what we are likely to discover about space, the solar system and our origins. It is the first step on a very long journey that will take us far into the future.

'I see it as like the famous explorer Sir Walter Raleigh going out and bringing back a potato from South America,' says Sara. 'It is the beginnings of what could be an amazing frontier.'