Turkey’s National Security Council, with an unprecedented tone of decisiveness,

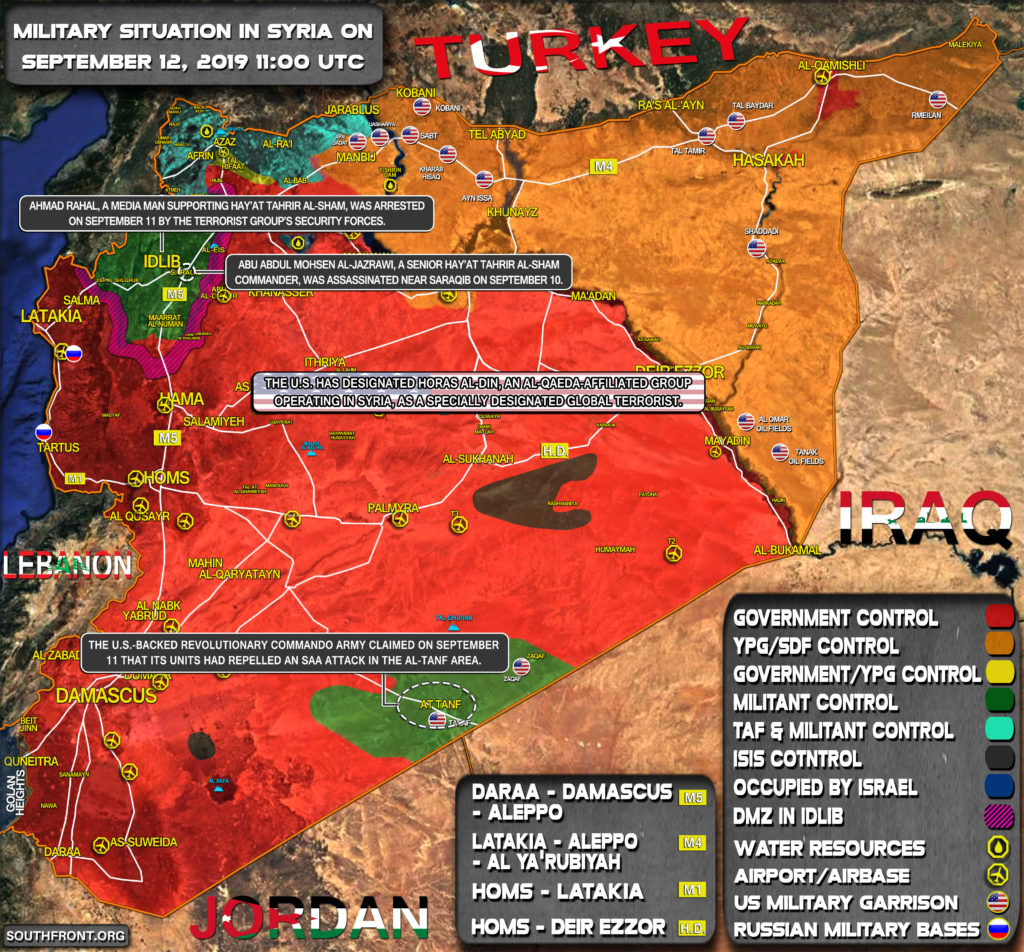

stated that Turkey would establish a 280-mile safe zone area spanning from the Euphrates River to the Syrian-Turkish-Iraqi border. It would drive Washington’s proxy, the People’s Protection Units (YPG)—the Syrian armed branch of the Marxist Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)—some twenty to twenty-five miles away from the Turkish border. This prompted the rush of American officials to Ankara for dissuasion. After tough negotiations, Turkey held off its unilateral military offensive against YPG in favor of

a joint Turko-American safe zone.

Yet having learned lessons from past American delaying of such agreements, particularly in the Manbij Province, Turkey’s minister of foreign affairs, Mevlut Cavusoglu,

cautioned that “Turkey won’t allow U.S. to stall the process for the operation in east of Euphrates like they did in Manbij.” Hulusi Akar, Turkey’s defense minister also

warned, “Turkey is holding out for a northern Syrian safe zone of between 30 and 40 km in depth and will not hesitate to take unilateral action if the United States fails to meet its demand.” This shows that the possibility of a Turkish incursion is still high as ever.

The U.S.-YPG honeymoon has been going on for four years. At numerous times, Turkey has threatened to act militarily against the YPG, expressing its extreme annoyance for Washington’s overt loyalty to a non-state actor that it perceives as a top national security threat. Given this, what is different now that makes a Turkish incursion likelier than before? The answer is in the shifting regional and international politics, as well as the level of Turkey’s readiness to conduct such a task.

The latest S-400 saga taught Ankara that it can shrug off Washington’s threats with a “stand your ground” approach. Despite America’s temper tantrum, Ankara purchased a major Russian armament—and the world didn’t come to an end for the Turks! Also, the same S-400 hubbub taught Washington that it has basically reached its limits of coercion on Turkey. Consequently, in a sharp U-turn, President Donald Trump began to blame his predecessor, Barack Obama, for the S400 debacle saying “

it is not Turkey's or Erdogan’s fault.” Trump also brought more than forty Republican senators to the White House to

dissuade them from imposing sanctions on Turkey.

Then there is the Russia factor. Ankara has Moscow to back its claims in the eastern Euphrates just like it did before the successful Afrin offensive against YPG in 2018. In an unusually harsh tone, Russian Col. Gen. Sergei Rudskoy

said “the U.S. occupation forces are hijacking oil fields and facilities in the Syrian al-Jazeera area, and they are continuing to train terrorist groups.” This change of tone came after Russian IL-76s, loaded with S-400 hardware, touched down in Ankara. Furthermore, at the Astana Summit in Kazakhstan on August 2, Russia, Iran and Turkey signed a

joint statement that rejects “separatist agendas aimed at undermining the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Syria as well as threatening the national security of neighboring countries.”

In addition, the rapid growth of Turkey’s military and intelligence capabilities have liberated Turkey from the threats of American and European arms embargoes that have in the past hampered the Turkish military’s operational capacity. Gone are the years that the U.S. Congress swiftly rejected Turkey’s request to buy such arms as Super Cobra AH-1 helicopters and Predator unmanned aerial vehicles which Turkey desperately needed to combat terrorism. As the Turkish proverb goes, “A bad landlord will motivate you to buy a house of your own!”

Turkey is now mostly self-sufficient and is able to produce its own helicopters, armored vehicles, short to medium range missiles and armed unmanned aerial vehicles.

The Turkish National Intelligence Organization (MIT) has greatly improved its operational ability too. In Syria, the MIT works closely with the local tribes and engages in intelligence gathering. In May, with the MIT at the helm, two hundred Syrian Arab tribes

united against the YPG in Turkey’s Urfa city and formed the Council of the Syrian Tribes and Clans. Most of those tribes

have a negative view of the YPG. For instance, Manbij’s prominent tribes, Baghara, Ghanaim Bani Said, Naim, Fennel, Popna, Aldamalkh, Majadameh and Al-Bustalan, clearly expressed their anger in reaction to the YPG’s call for compulsory enlistment and

invited Turkey to “liberate” their town. The MIT also

successfully captured the suspect of the deadly massacre of 2013 that cost fifty-three lives in the Turkish town of Reyhanli and brought him in from Syria. Furthermore, in cooperation with the Turkish military, the MIT has assassinated top PKK members in northern Iraq.

Finally, a possible Turkish incursion into northern Syria should be analyzed within the context of Turkey’s military presence in northern Iraq. In the last five years, Turkey has set up military bases (some thirteen of them) in major areas such as Dohuk, Erbil, Suleymaniye and Zaho, indicating that the Turkish presence in northern Iraq is long term. Once unsympathetic to Turkey’s headways, the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) under Masoud Barzani and the Iraqi central government have now

welcomed the Turkish presence as the PKK, their common adversary, has become too powerful in the aftermath of ISIS’ defeat. In this vein, in northern Iraq, the Turkish military is currently executing Operation Claw, a major military incursion aimed at eradicating PKK training sites in Avasin, Haftanin, Hakurk, Zap, and most importantly Qandil—the main PKK camp. Once believed impenetrable, the PKK’s Qandil headquarters is now in Turkey’s crosshairs. This would sever the highway of militants between Qandil and the lands east of the Euphrates. Therefore, the timing of a Turkish operation in northern Syria greatly depends on the status of Operation Claw. Since Turkey has made substantial progress there, it should be expected that Turkey’s Syria incursion is on the horizon.

In conclusion, the waning of America’s influence in the Middle East, the green light from regional actors—Russia, Iran, the Kurdish Regional Government, and the Iraqi Central Government, as well as the high-level readiness of the Turkish military and intelligence, makes a Turkish incursion in Syria very conducive. Even with this week’s implementation of the

jointly patrolled U.S.-Turko safe zone in northern Syria, last month’s fragile agreement doesn’t seem like it is going to hold. As Aaron Stein put it for

War on the Rocks, “If Ankara chooses to intervene, the reality is that the U.S. military would not be in a position to stop it.” Washington’s abject loneliness gives the impression that it is stuck with a very unpopular non-state actor which is unlikely to help advance its interests. It’s probably time to stop alienating Ankara and mend ties. Without Turkey, the US will have a hard time winning in the Middle East.

sputniknews.com

southfront.org

southfront.org

southfront.org

southfront.org

southfront.org

southfront.org

southfront.org

southfront.org