Quite a number of posts across the Forum refer to the I Ching. However, there did not seem to be a thread about its translations, but there are many. Below are mentioned just two, that of Richard Wilhelm and Alfred Huang, though as you will see the notes to the first took up much more space, as I discovered that the German-Chinese cultural exchange in the late 19th and early 20th century was more significant than I had previously realized.

The I Ching or Book of Changes by Richard Wilhelm (originally German) and translated into English by Cary F. Banes proved to be a milestone and popularized the I Ching in the Western world. There are serveral reprints and editions. Like this from Princeton University 1967, from 1989, from 1995, and the following (image) is coming out in April 2026.

For years this book was a stable, but it took a long time to address an issue, However some years ago, a Dutch I Ching researcher, Harmen Mesker, who edited the Dutch version, wrote in a post on The Dao Bums forum where he linked to four blog entries about work he had done:

Going back to the source: the manuscripts of Richard Wilhelm (3)

The discussion earlier about the oversight in Wilhelm's original manuscript, I found when reading in The Dao Bums thread: Is Alfred Huang a reliable translator? The people say that both the translation of Wilhelm and Huang are are coloured by Confucianism. Every translator has an angle so that is as expected. The work in question, which is also the copy I have, is:

The Complete I Ching ― 10th Anniversary Edition: The Definitive Translation by Taoist Master Alfred Huang

Alfred Huang has had an interesting life and spent many years in prison at a time when I Ching and Taoism was suppressed. It is a book made by a translator and practitioner with more life experience than most, and I think it carries over to his work, based in tradition but also open and flexible. I could not find any information that he has passed. By now he would be 104? Even if he made it to his late nineties that alone would be worthy of respect.

Another book of his is The Numerology of the I Ching: A Sourcebook of Symbols, Structures, and Traditional Wisdom Many reviewers say this is more for those who are familiar with I Ching already. The description on the Amazon page includes:

There are many other translations of the I Ching. Some are surely better than others, but all insights are hardly contained in one book. Besides the letters and lines of the I Ching and its translation(s), there is also what is between the lines. What does an expression mean for us?

I am hoping someone else has comments to offer.

The I Ching or Book of Changes by Richard Wilhelm (originally German) and translated into English by Cary F. Banes proved to be a milestone and popularized the I Ching in the Western world. There are serveral reprints and editions. Like this from Princeton University 1967, from 1989, from 1995, and the following (image) is coming out in April 2026.

For years this book was a stable, but it took a long time to address an issue, However some years ago, a Dutch I Ching researcher, Harmen Mesker, who edited the Dutch version, wrote in a post on The Dao Bums forum where he linked to four blog entries about work he had done:

Below are some excerpt from one of them:About a year ago I went to Germany to resolve some questions that I had about Wilhelm's translation. Those interested might want to read my 4-part travel diary about my journey and the things I discovered:

http://www.yjcn.nl/wp/going-back-to-the-source-the-manuscripts-of-richard-wilhelm-1/

http://www.yjcn.nl/wp/going-back-to-the-source-the-manuscripts-of-richard-wilhelm-2/

http://www.yjcn.nl/wp/going-back-to-the-source-the-manuscripts-of-richard-wilhelm-3/

http://www.yjcn.nl/wp/going-back-to-the-source-the-manuscripts-of-richard-wilhelm-4-the-end/

Going back to the source: the manuscripts of Richard Wilhelm (3)

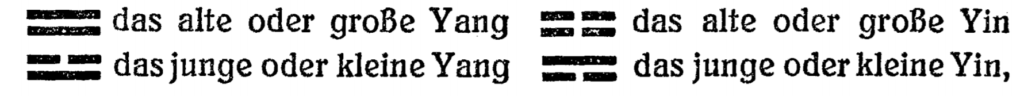

Some say that a book written by a real Chinese would be preferable but Richard Wilhelm (1873-1930) was more than an ordinary German sinologist:You might wonder why I am making such a fuzz out of something that seems to be a minor detail in Wilhelm’s translation of the Yijing. Is it really important whether ⚍ and ⚎ are either called shao yin 少陰 or shao yang 少陽? Are the names really that important?

In fact they are. The concept and usage of the sixiang 四象, the Four Images ⚌ ⚏ ⚍ ⚎ goes beyond their designations: they are linked to the seasons, and out of this link entire new concepts are constructed. Hexagrams can be seen as a combination of several two-line symbols. If you don’t know their proper names you will not know how to properly link the symbols to the seasons, and if you are interested in time related consultations with the Yi this can get you in serious trouble. The names are important because these names are also used as names for the seasons: tai yang 太陽 is Summer (it is also a name for the sun), tai yin 太陰 is Winter, shao yang 少陽 is Spring and shao yin 少陰 is Autumn. If you want to use these names to link the seasons to the sixiang you must know the proper names of these symbols.

In China this has never been an argument. There was no confusion about the names of ⚍ and ⚎.

[...]

But we, the readers in the West, do have this discussion, and it started with Wilhelm’s Yijing translation in which he switched the names of shao yin and shao yang:

‘⚍ the young or small Yang, ⚎ the young or small Yin.’

This is not the Chinese way. Did he always name the sixiang like this? No. In front of me were two pages that proved this.

[...]

Again Wilhelm gave the Four Symbols their original Chinese names! This document was dated 1914. The other loose papers that I mentioned earlier are probably from around 1919. For at least five years or so Wilhelm did not have any doubts or change in the names of the sixiang. So how did the switch end up in his book? The last maps in the box should be decisive: they contained the handwritten manuscript that was to become the final version of the draft for his book.

[...]

The text still contains many corrections and there are several leaflets inserted with notes and remarks, like the small paper that became the footnote about James Legge’s translation. But it can immediately be recognized as the manuscript that was the source for his book. All the corrections that are made in this manuscript are also found in his book. So how does this final draft give the names of the sixiang? I thumbed through the manuscript until I found the relevant page.

‘⚌ das alte oder große yang ⚏ das alte oder große yin

⚍ das junge oder kleine yang ⚎ das junge oder kleine yin’

I was disappointed. This was exactly how it ended up in Wilhelm’s book. I was hoping that the names of the sixiang in the manuscript would correspond with his earlier notes. I was hoping that I could say, Look! Wilhelm wrote it correctly! The publisher screwed up, not Wilhelm!’ But the manuscript proved otherwise. The names in the manuscript were the same as the names in Wilhelm’s book. I closed the manuscript and put it back in the map. My job at the archive of the Bayern Akademie der Wissenschaften was finished.

How did the name switch end up in the handwritten manuscript? We will probably never know. My personal guess is that it is a slip of the pen: two times Wilhelm gave the Four Symbols the right names, only the final draft of his book shows the name switch. Had he done this on purpose he would no doubt have mentioned it, in the same way he mentioned alternative readings of a line or character in Book III of his translation.

I did not find conclusive facts, but for me the matter was settled.

The German Wiki has:theologian and missionary. He lived in China for 25 years, became fluent in spoken and written Chinese, and grew to love and admire the Chinese people. He is best remembered for his translations of philosophical works from Chinese into German that in turn have been translated into other major languages of the world, including English. His translation of the I Ching is still regarded as one of the finest, as is his translation of The Secret of the Golden Flower; both were provided with introductions by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, who was a personal friend.

Looking up Lao Naixuan, shows he was an influential thinker and official. One paper that mentions his work in some detail, this is not I Ching related, but it shows that Wilhelm was so much more than a translator.Intermezzo in Beijing[edit] Edit source]

From 1922 to 1924, Wilhelm worked as a scientific advisor in the German legation in Beijing, and he also taught at Peking University. Here he also translated the I Ching (Book of Changes) into German. The edition he used as a model for his translation was the Chou I Djung from the Kangxi period (1662–1723). With the help of his teacher Lau Nai Süan (Lao Naixuan; 1843–1921), he created his edition, which was translated into many Western languages. The commentary included quotations from both the Bible and Goethe, but also ideas from Western philosophers and Protestant, Parsi and ancient Greek theology. Wilhelm thus showed many parallels to Chinese wisdom.

[...]The German-Chinese University in Qingdao as a Space of Circulation During the Late Qing and Early Republican Era

The Case of the Reform of Chinese Penal Law

By Iwo Amelung - Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, Deutschland

Abstract

This paper reconstructs and analyses the dialogue between conservative German legal scholars and Chinese officials involved in the reform of Chinese penal law during the late Qing period. It shows that, to some extent, the colonial setting – and the German-Chinese University in Tsing-tao as a very special space of circulation – offered opportunities for a surprisingly multi-faceted Sino-German intellectual exchange. It also makes clear that not only progressive Chinese scholars could thrive by appropriating ‘Western’ ideas, but that this could be true for more conservative officials and scholars as well.

[...]The problem of terminologies was addressed by the Übersetzungsanstalt, which proved to be quite productive. As Romberg had advocated, it aimed to counter the Anglo-American dominance in the development of technical terms. At the same time, it tackled the problem of standardising terminologies, an issue that had hindered Chinese scientific practice – particularly in science and technology education – since the mid nineteenth century, and actually only was partially resolved after 1949. The translation department published at least two dictionaries. The more well known was Richard Wilhelm’s (1873‑1930) rather voluminous Deutsch-englisch-chinesisches Fachwörterbuch (De Ying Hua wen kexue zidian 德英華文科學字典), which was published in 1911. As Dorothea Wippermann’s paper in this volume shows, however, its compilation had been carried out largely independently from the university. Although the dictionary remained quite obscure, we know that Karl Hemeling (1878‑1925) used it for his famous Guanhua dictionary of 1916, though not all terms were adopted (1916, iii).

Looking for a picture of Lao Naixuan, there was this:The most well-known representative of the conservative camp was the Minister of Education Zhang Zhidong, one of the most influential Chinese officials during the last years of the Qing dynasty. He was supported by lesser, but still quite influential Qing officials, such as especially Lao Naixuan 勞乃宣 (1843‑1920). When the first draft of the ‘New penal code’ was circulated, Zhang Zhidong heavily criticised it. The main objections of the conservatives were, first, that there were no special penalties for perpetrators against Confucian values (especially filial piety) and, second, that it failed to punish consensual sex of unmarried women.

Regarding the legal reforms, Zhang Zhidong argued:

What cannot be changed is the moral order; this is not part of the legal system, but relates to the kingly way, it isn’t an apparatus, it is the ‘art of the heart’ and not a craft. (2015, 74)

Most of the responses of the law reformers stressed that these issues were not the business of the courts, but private matters related to education. Moreover, they were not enforceable and thus, in the eyes of law reformers, constituted dead letters. When Zhang Zhidong died in 1909, his role as the main proponent of conservative criticism or, to use the words of the times, the head of the ritual faction, was taken over by the aforementioned Lao Naixuan, who after the fall of the Qing Dynasty relocated to Qingdao and collaborated with Richard Wilhelm.

The discussion earlier about the oversight in Wilhelm's original manuscript, I found when reading in The Dao Bums thread: Is Alfred Huang a reliable translator? The people say that both the translation of Wilhelm and Huang are are coloured by Confucianism. Every translator has an angle so that is as expected. The work in question, which is also the copy I have, is:

The Complete I Ching ― 10th Anniversary Edition: The Definitive Translation by Taoist Master Alfred Huang

Alfred Huang has had an interesting life and spent many years in prison at a time when I Ching and Taoism was suppressed. It is a book made by a translator and practitioner with more life experience than most, and I think it carries over to his work, based in tradition but also open and flexible. I could not find any information that he has passed. By now he would be 104? Even if he made it to his late nineties that alone would be worthy of respect.

Another book of his is The Numerology of the I Ching: A Sourcebook of Symbols, Structures, and Traditional Wisdom Many reviewers say this is more for those who are familiar with I Ching already. The description on the Amazon page includes:

As an example of an insight from the book, Huang writes, though the hexagram signs have been replaced with brackets:The first book to cover the complete Taoist teachings on form, structure, and symbol in the I Ching.

• Provides many new patterns and diagrams for visualizing the layout of the 64 hexagrams.

• Includes advanced teachings on the hosts of the hexagrams, the mutual hexagrams, and the core hexagrams.

While there are 64 hexagrams, not all are equally known:After I wrote The Complete I Ching I realized that the hidden meaning of the I Ching is seeking harmony. Because Heaven and Earth embrace the virtue of creating and sustaining new lives and events, they are reflected in the first two gua and the I Ching, Initiating () and Responding, (). The last two gua, Already Fulfilled () and Not Yet Fulfilled, express how to follow the law of change, that is, how to move from imbalance to balance and from disharmony to harmony. - p 157

There are thirty-two gua, sixteen in the Upper Canon and sixteen in the Lower Canon, which are most familiar to the Chinese. The Chinese have applied them in their daily lives for thousands of years. The I Ching has become part of the Chinese collective unconscious. Many phrases of the appended texts are still used in daily conversation, although most Chinese do not know these phrases come from the I Ching. Overall the I Ching has exerted a subtle influence upon Chinese thought and culture. - p 119

If less than the whole I-Ching has proven helpful to many people for centuries, it shows that one can gain from studying or reading the I Ching without knowing all that there is to know. In practical terms we may have a question in mind and look up what perspective and food for thought the I Ching has to offer.Besides the thirty-two gua above, there are another four gua, two in the Upper Cannon and another two in the Lower Cannon, that are familiar in intellectual circles. - p. 124

There are many other translations of the I Ching. Some are surely better than others, but all insights are hardly contained in one book. Besides the letters and lines of the I Ching and its translation(s), there is also what is between the lines. What does an expression mean for us?

I am hoping someone else has comments to offer.