I thought this recent SOTT article was peripherally related to this topic, especially with respect to how it "gamifies" the education and discipline of children.

www.sott.net

www.sott.net

How Inuit parents teach kids to control their anger

Back in the 1960s, a Harvard graduate student made a landmark discovery about the nature of human anger. At age 34, Jean Briggs traveled above the Arctic Circle and lived out on the tundra for 17 months. There were no roads, no heating systems,...

Back in the 1960s, a Harvard graduate student made a landmark discovery about the nature of human anger.

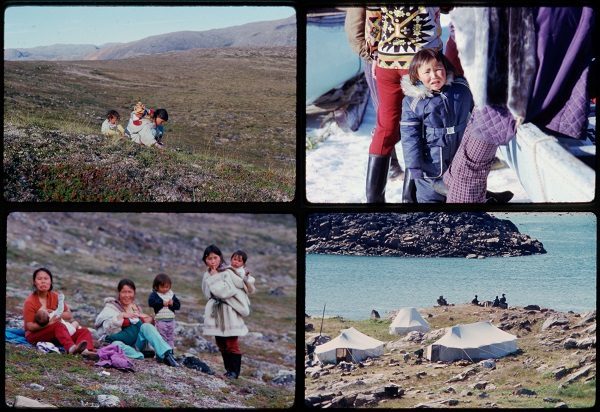

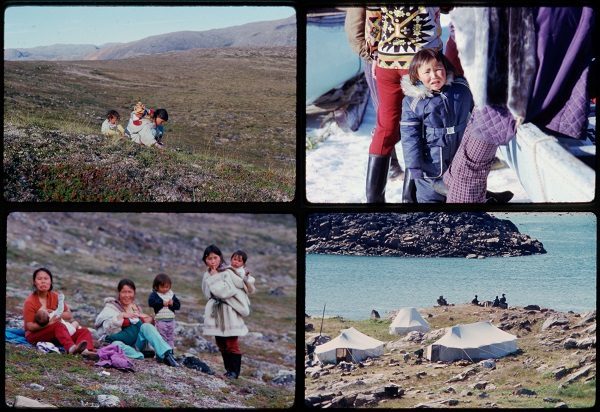

At age 34, Jean Briggs traveled above the Arctic Circle and lived out on the tundra for 17 months. There were no roads, no heating systems, no grocery stores. Winter temperatures could easily dip below minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

Briggs persuaded an Inuit family to "adopt" her and "try to keep her alive," as the anthropologist wrote in 1970.

At the time, many Inuit families lived similar to the way their ancestors had for thousands of years. They built igloos in the winter and tents in the summer. "And we ate only what the animals provided, such as fish, seal and caribou," says Myna Ishulutak, a film producer and language teacher who lived a similar lifestyle as a young girl.

Briggs quickly realized something remarkable was going on in these families: The adults had an extraordinary ability to control their anger.

"They never acted in anger toward me, although they were angry with me an awful lot," Briggs told the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. in an interview.

Even just showing a smidgen of frustration or irritation was considered weak and childlike, Briggs observed.

For instance, one time someone knocked a boiling pot of tea across the igloo, damaging the ice floor. No one changed their expression. "Too bad," the offender said calmly and went to refill the teapot.

In another instance, a fishing line - which had taken days to braid - immediately broke on the first use. No one flinched in anger. "Sew it together," someone said quietly.

By contrast, Briggs seemed like a wild child, even though she was trying very hard to control her anger. "My ways were so much cruder, less considerate and more impulsive," she told the CBC. "[I was] often impulsive in an antisocial sort of way. I would sulk or I would snap or I would do something that they never did."

Briggs, who died in 2016, wrote up her observations in her first book, Never in Anger. But she was left with a lingering question: How do Inuit parents instill this ability in their children? How do Inuit take tantrum-prone toddlers and turn them into cool-headed adults?

Then in 1971, Briggs found a clue.

She was walking on a stony beach in the Arctic when she saw a young mother playing with her toddler - a little boy about 2 years old. The mom picked up a pebble and said, "'Hit me! Go on. Hit me harder,'" Briggs remembered.

The boy threw the rock at his mother, and she exclaimed, "Ooooww. That hurts!"

Briggs was completely befuddled. The mom seemed to be teaching the child the opposite of what parents want. And her actions seemed to contradict everything Briggs knew about Inuit culture.

"I thought, 'What is going on here?' " Briggs said in the radio interview.

Turns out, the mom was executing a powerful parenting tool to teach her child how to control his anger - and one of the most intriguing parenting strategies I've come across.

No scolding, no timeouts

It's early December in the Arctic town of Iqaluit, Canada. And at 2 p.m., the sun is already calling it a day. Outside, the temperature is a balmy minus 10 degrees Fahrenheit. A light snow is swirling.

I've come to this seaside town, after reading Briggs' book, in search of parenting wisdom, especially when it comes to teaching children to control their emotions. Right off the plane, I start collecting data.

I sit with elders in their 80s and 90s while they lunch on "country food" -stewed seal, frozen beluga whale and raw caribou. I talk with moms selling hand-sewn sealskin jackets at a high school craft fair. And I attend a parenting class, where day care instructors learn how their ancestors raised small children hundreds - perhaps even thousands - of years ago.

Across the board, all the moms mention one golden rule: Don't shout or yell at small children.

Traditional Inuit parenting is incredibly nurturing and tender. If you took all the parenting styles around the world and ranked them by their gentleness, the Inuit approach would likely rank near the top. (They even have a special kiss for babies, where you put your nose against the cheek and sniff the skin.)

The culture views scolding - or even speaking to children in an angry voice - as inappropriate, says Lisa Ipeelie, a radio producer and mom who grew up with 12 siblings. "When they're little, it doesn't help to raise your voice," she says. "It will just make your own heart rate go up."

Even if the child hits you or bites you, there's no raising your voice?

"No," Ipeelie says with a giggle that seems to emphasize how silly my question is. "With little kids, you often think they're pushing your buttons, but that's not what's going on. They're upset about something, and you have to figure out what it is."

Traditionally, the Inuit saw yelling at a small child as demeaning. It's as if the adult is having a tantrum; it's basically stooping to the level of the child, Briggs documented.

Elders I spoke with say intense colonization over the past century is damaging these traditions. And, so, the community is working hard to keep the parenting approach intact.

Goota Jaw is at the front line of this effort. She teaches the parenting class at the Arctic College. Her own parenting style is so gentle that she doesn't even believe in giving a child a timeout for misbehaving.

"Shouting, 'Think about what you just did. Go to your room!' " Jaw says. "I disagree with that. That's not how we teach our children. Instead you are just teaching children to run away."

And you are teaching them to be angry, says clinical psychologist and author Laura Markham. "When we yell at a child - or even threaten with something like 'I'm starting to get angry,' we're training the child to yell," says Markham. "We're training them to yell when they get upset and that yelling solves problems."

In contrast, parents who control their own anger are helping their children learn to do the same, Markham says. "Kids learn emotional regulation from us."

I asked Markham if the Inuit's no-yelling policy might be their first secret of raising cool-headed kids. "Absolutely," she says.

Playing soccer with your head

Now at some level, all moms and dads know they shouldn't yell at kids. But if you don't scold or talk in an angry tone, how do you discipline? How do you keep your 3-year-old from running into the road? Or punching her big brother?

For thousands of years, the Inuit have relied on an ancient tool with an ingenious twist: "We use storytelling to discipline," Jaw says.

Jaw isn't talking about fairy tales, where a child needs to decipher the moral. These are oral stories passed down from one generation of Inuit to the next, designed to sculpt kids' behaviors in the moment. Sometimes even save their lives.

For example, how do you teach kids to stay away from the ocean, where they could easily drown? Instead of yelling, "Don't go near the water!" Jaw says Inuit parents take a pre-emptive approach and tell kids a special story about what's inside the water. "It's the sea monster," Jaw says, with a giant pouch on its back just for little kids.

"If a child walks too close to the water, the monster will put you in his pouch, drag you down to the ocean and adopt you out to another family," Jaw says.

"Then we don't need to yell at a child," Jaw says, "because she is already getting the message."

Inuit parents have an array of stories to help children learn respectful behavior, too. For example, to get kids to listen to their parents, there is a story about ear wax, says film producer Myna Ishulutak.

"My parents would check inside our ears, and if there was too much wax in there, it meant we were not listening," she says.

And parents tell their kids: If you don't ask before taking food, long fingers could reach out and grab you, Ishulutak says.

Then there's the story of northern lights, which helps kids learn to keep their hats on in the winter.

"Our parents told us that if we went out without a hat, the northern lights are going to take your head off and use it as a soccer ball," Ishulutak says. "We used to be so scared!" she exclaims and then erupts in laughter.

At first, these stories seemed to me a bit too scary for little children. And my knee-jerk reaction was to dismiss them. But my opinion flipped 180 degrees after I watched my own daughter's response to similar tales - and after I learned more about humanity's intricate relationship with storytelling.

Oral storytelling is what's known as a human universal. For tens of thousands of years, it has been a key way that parents teach children about values and how to behave.

Modern hunter-gatherer groups use stories to teach sharing, respect for both genders and conflict avoidance, a recent study reported, after analyzing 89 different tribes. With the Agta, a hunter-gatherer population of the Philippines, good storytelling skills are prized more than hunting skills or medicinal knowledge, the study found.

Today many American parents outsource their oral storytelling to screens. And in doing so, I wonder if we're missing out on an easy - and effective - way of disciplining and changing behavior. Could small children be somehow "wired" to learn through stories?

"Well, I'd say kids learn well through narrative and explanations," says psychologist Deena Weisberg at Villanova University, who studies how small children interpret fiction. "We learn best through things that are interesting to us. And stories, by their nature, can have lots of things in them that are much more interesting in a way that bare statements don't."

Stories with a dash of danger pull in kids like magnets, Weisberg says. And they turn a tension-ridden activity like disciplining into a playful interaction that's - dare, I say it - fun.

"Don't discount the playfulness of storytelling," Weisberg says. "With stories, kids get to see stuff happen that doesn't really happen in real life. Kids think that's fun. Adults think it's fun, too."

Why don't you hit me?

Back up in Iqaluit, Myna Ishulutak is reminiscing about her childhood out on the land. She and her family lived in a hunting camp with about 60 other people. When she was a teenager, her family settled in a town.

"I miss living on the land so much," she says as we eat a dinner of baked Arctic char. "We lived in a sod house. And when we woke up in the morning, everything would be frozen until we lit the oil lamp."

I ask her if she's familiar with the work of Jean Briggs. Her answer leaves me speechless.

Ishulutak reaches into her purse and brings out Briggs' second book, Inuit Morality Play, which details the life of a 3-year-old girl dubbed Chubby Maata.

"This book is about me and my family," Ishulutak says. "I am Chubby Maata."

In the early 1970s, when Ishulutak was about 3 years old, her family welcomed Briggs into their home for six months and allowed her to study the intimate details of their child's day-to-day life.

What Briggs documented is a central component to raising cool-headed kids.

When a child in the camp acted in anger - hit someone or had a tantrum - there was no punishment. Instead, the parents waited for the child to calm down and then, in a peaceful moment, did something that Shakespeare would understand all too well: They put on a drama. (As the Bard once wrote, "the play's the thing wherein I'll catch the conscience of the king.")

"The idea is to give the child experiences that will lead the child to develop rational thinking," Briggs told the CBC in 2011.

In a nutshell, the parent would act out what happened when the child misbehaved, including the real-life consequences of that behavior.

The parent always had a playful, fun tone. And typically the performance starts with a question, tempting the child to misbehave.

For example, if the child is hitting others, the mom may start a drama by asking: "Why don't you hit me?"

Then the child has to think: "What should I do?" If the child takes the bait and hits the mom, she doesn't scold or yell but instead acts out the consequences. "Ow, that hurts!" she might exclaim.

The mom continues to emphasize the consequences by asking a follow-up question. For example: "Don't you like me?" or "Are you a baby?" She is getting across the idea that hitting hurts people's feelings, and "big girls" wouldn't hit. But, again, all questions are asked with a hint of playfulness.

The parent repeats the drama from time to time until the child stops hitting the mom during the dramas and the misbehavior ends.

Ishulutak says these dramas teach children not to be provoked easily. "They teach you to be strong emotionally," she says, "to not take everything so seriously or to be scared of teasing."

Psychologist Peggy Miller, at the University of Illinois, agrees: "When you're little, you learn that people will provoke you, and these dramas teach you to think and maintain some equilibrium."

In other words, the dramas offer kids a chance to practice controlling their anger, Miller says, during times when they're not actually angry.

This practice is likely critical for children learning to control their anger. Because here's the thing about anger: Once someone is already angry, it is not easy for that person to squelch it - even for adults.

"When you try to control or change your emotions in the moment, that's a really hard thing to do," says Lisa Feldman Barrett, a psychologist at Northeastern University who studies how emotions work.

But if you practice having a different response or a different emotion at times when you're not angry, you'll have a better chance of managing your anger in those hot-button moments, Feldman Barrett says.

"That practice is essentially helping to rewire your brain to be able to make a different emotion [besides anger] much more easily," she says.

This emotional practice may be even more important for children, says psychologist Markham, because kids' brains are still developing the circuitry needed for self-control.

"Children have all kinds of big emotions," she says. "They don't have much prefrontal cortex yet. So what we do in responding to our child's emotions shapes their brain."

Markham recommends an approach close to that used by Inuit parents. When the kid misbehaves, she suggests, wait until everyone is calm. Then in a peaceful moment, go over what happened with the child. You can simply tell them the story about what occurred or use two stuffed animals to act it out.

"Those approaches develop self-control," Markham says.

Just be sure you do two things when you replay the misbehavior, she says. First, keep the child involved by asking many questions. For example, if the child has a hitting problem, you might stop midway through the puppet show and ask,"Bobby, wants to hit right now. Should he?"

Second, be sure to keep it fun. Many parents overlook play as a tool for discipline, Markham says. But fantasy play offers oodles of opportunities to teach children proper behavior.

"Play is their work," Markham says. "That's how they learn about the world and about their experiences."

Which seems to be something the Inuit have known for hundreds, perhaps even, thousands of years.