palestine

Dagobah Resident

Hello,I would like to propose a question to the Cassiopaeans.

I came across a text written by someone who worked with A. Lobaczewski in the USA. He wrote the following:

The Psychological Roots of Communism | Marian Wasilewski

Marian WASILEWSKI - “The Psychological Roots of Communism”

The author speaks of a phenomenon of intelligent design, and it is impossible to determine its origin.The effect of this phenomenon translates into a "democracy-like" influence in the West and, in the author's words, a "totalitarian" influence in the Eastern part of the world.

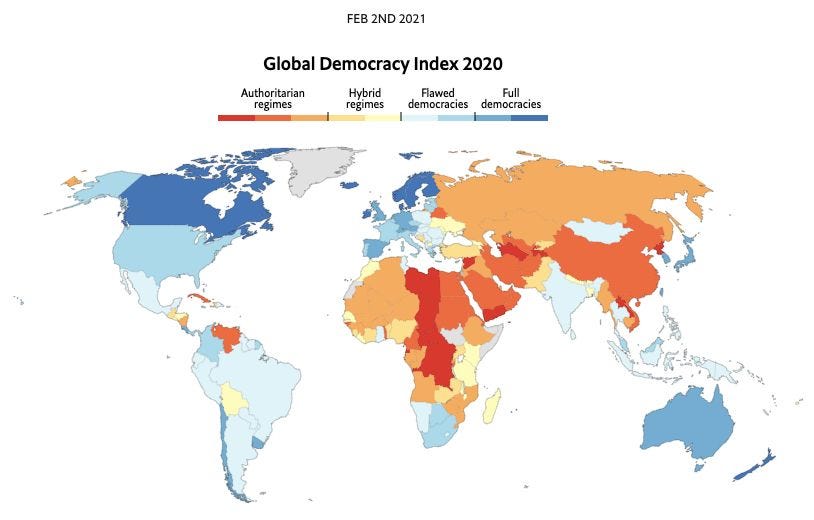

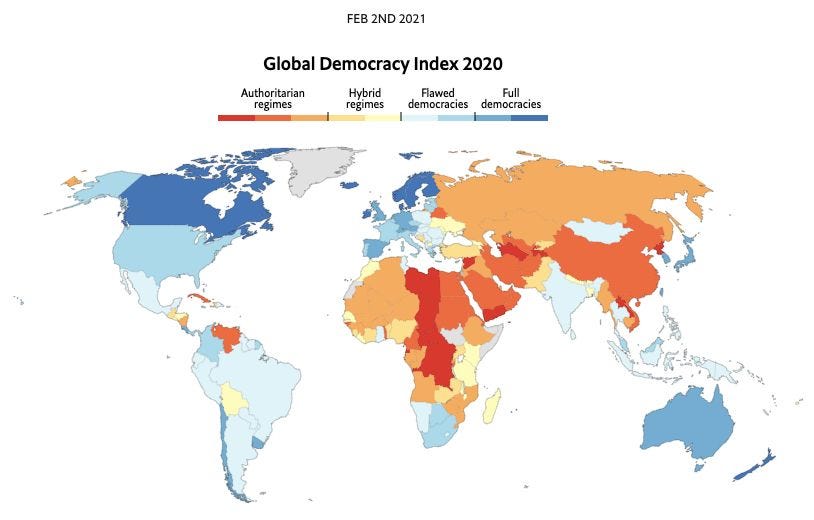

I did some research and came across the following map:

As you can see, the phenomenon suggested by Mr. Wasilewski seems to be illustrated. However, the map indicates that these are "authoritarian" regimes (not "totalitarian").

M. Wasilewski wrote his text in 1987, and his consideration of the two "forces" is a +/-. For him, while Communism had caused a lot of damage, democracy was a salvation.

However, we see today that "democracy" can also suffer from terrible degeneration.

In my opinion, Mr. Wasilewski might have noticed/understood that the world is subject to two major influences that have an impact on the basic political structure. He determined that it was a +/- radius.

I would tend to observe that Russia, China, Korea, etc., do indeed tend to attribute more power to the state, out of a principle that comes from who knows where. This does not constitute a "-" situation, but an even reflection of "democracy".

The second line of force would be "authoritarian," a neutral situation for "a strong state."

So, here are the variables for my question!

Is there really a kind of double polarization of political regimes in the world?

Is it "natural"?

What conditions it?

We observe that democratic regimes have preferred the Capitalist ideology, while Eastern regimes overwhelmingly favor Communism.

Today, we are observing a pathocratic drift in the West (England, France, Germany, Biden's USA), and we have had a totalitarian drift each time with Communism. It becomes strange to observe that "the World" produces a shell that will find its footing in an ideology more likely to degenerate into pathocracy. I would suspect an intelligent STS design, but I am retaining, too, a "natural" alternative. In this case, the factor of degeneration towards pathocracy intervenes in another place.

I would be happy if you could tell me what you think.

I really appreciate the author's initial idea—it's as if he had "seen" a structure of the world. It's very original.

What's very interesting is that A. Lobaczewski explained that pathocracy developed from an ideology. Here, we have the existence of a prior, hierarchically superior shell (pluralism > Capitalism). We could thus define more precise foundations for the phenomenon of pathocracy.

(translated from French)

I came across a text written by someone who worked with A. Lobaczewski in the USA. He wrote the following:

The Psychological Roots of Communism | Marian Wasilewski

Marian WASILEWSKI - “The Psychological Roots of Communism”

I. THE POLITICAL DIVISION OF THE WORLD

Why, Arjuna, in this decisive moment of danger, are you overcome by this shameful despair, unworthy of a warrior, which closes the heavens and leads to disgrace? (1). Bhagavad-Gita (II - 2)

There is an ancient Indian legend in which the god Shiva takes part in an endless dance of happiness with his divine wife Shakhty . Their children are the forms of the manifested world. In Chinese culture, there are two elements, Yin and Yang, which, in creating the world, determine each other and cannot exist independently. In our own times, we talk of the twofold nature of all existence. And although our intuition tries to tell us of the basic unity of all matter, our senses and intellect assure us that everything is bipolar and has an opposite. Philosophers and scientists call this phenomenon the binary polarization of existence.

Much points to the fact that this dissociation, which we must accept as a universal law, also occurs in social life. It can even be seen in ancient Biblical symbolism, as in the contrasting characters of Abel and Cain. Every historical period gives us numerous examples of this dissociation. Today’s political division of the world is also an expression thereof.

The two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union , constitute the poles of this division. They are opposite on all points-world outlook, ideology, politics, and ethics - although in the most general sense they both derive from the same human cultural heritage. Between these poles there exists a tension which expresses these differences. Colloquially, one speaks of two systems: the democratic (or pluralistic) and the totalitarian.

The author speaks of a phenomenon of intelligent design, and it is impossible to determine its origin.The effect of this phenomenon translates into a "democracy-like" influence in the West and, in the author's words, a "totalitarian" influence in the Eastern part of the world.

I did some research and came across the following map:

As you can see, the phenomenon suggested by Mr. Wasilewski seems to be illustrated. However, the map indicates that these are "authoritarian" regimes (not "totalitarian").

M. Wasilewski wrote his text in 1987, and his consideration of the two "forces" is a +/-. For him, while Communism had caused a lot of damage, democracy was a salvation.

However, we see today that "democracy" can also suffer from terrible degeneration.

In my opinion, Mr. Wasilewski might have noticed/understood that the world is subject to two major influences that have an impact on the basic political structure. He determined that it was a +/- radius.

I would tend to observe that Russia, China, Korea, etc., do indeed tend to attribute more power to the state, out of a principle that comes from who knows where. This does not constitute a "-" situation, but an even reflection of "democracy".

The second line of force would be "authoritarian," a neutral situation for "a strong state."

So, here are the variables for my question!

Is there really a kind of double polarization of political regimes in the world?

Is it "natural"?

What conditions it?

We observe that democratic regimes have preferred the Capitalist ideology, while Eastern regimes overwhelmingly favor Communism.

Today, we are observing a pathocratic drift in the West (England, France, Germany, Biden's USA), and we have had a totalitarian drift each time with Communism. It becomes strange to observe that "the World" produces a shell that will find its footing in an ideology more likely to degenerate into pathocracy. I would suspect an intelligent STS design, but I am retaining, too, a "natural" alternative. In this case, the factor of degeneration towards pathocracy intervenes in another place.

I would be happy if you could tell me what you think.

I really appreciate the author's initial idea—it's as if he had "seen" a structure of the world. It's very original.

What's very interesting is that A. Lobaczewski explained that pathocracy developed from an ideology. Here, we have the existence of a prior, hierarchically superior shell (pluralism > Capitalism). We could thus define more precise foundations for the phenomenon of pathocracy.

(translated from French)