Is it permissible to challenge the official narrative on Syria?

Samir Saul and Rachad Antonius

Media ,

War Zone

January 6, 2020

A handout picture released by the official Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA), shows Syrian army units and pro-government forces deploying at an undisclosed location in the Atshan village in central province of Hama, on October 11, 2015.

Last month, two conferences were scheduled in Montreal as part of Vanessa Beeley’s

Canadian tour. As soon as they were announced, the speaker was subjected to volleys of invective, insults and slander from the proponents of the official narrative on Syria. The strategy was clear:

smear the person to distract attention from what she was saying, attack the messenger so that the message would not be heard. The conference scheduled at the Université de Montréal was cancelled. The other was held as planned at the Centre Saint-Pierre, despite pressures.

It drew a sellout crowd.

Beeley is an investigative journalist who has been on the ground in Syria and whose independent journalism has been recognized in Great Britain by a various institutions. Her links with the Arab world go back to her childhood; her father, Sir Harold Beeley, was a diplomat, a historian and an ambassador to the Middle East.

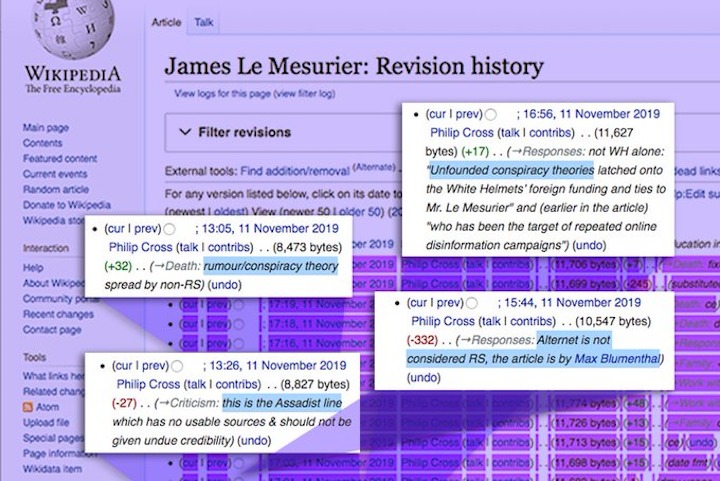

Beeley’s investigations contradict the official account on Syria. Among other things, she questioned the role of the White Helmets and showed that this organization was created in Turkey in 2013 by a British army officer,

James Le Mesurier. On the basis of official documents, she demonstrated that the White Helmets

were funded mainly by the British and American governments. She pointed out that they shared premises and even leadership with jihadist groups in Syria.

Wars and Lies

Every war is justified by an official narrative,

repeated over and over again. Then

reality catches up with it, truth comes out and the story falls apart, often after the fact. The narrative is then discredited, debunked and discarded. The war against Syria is no exception; many distortions and falsehoods are already discredited. Consider the following.

The downfall of the Syrian regime was presented as imminent in 2011; it is still in place. The conflict was supposed to be confessional;

it is not, despite all efforts to ignite sectarian discord. The war was described as civil; it is a national war against foreign interventions that have hardly been concealed and which have now turned into open American occupation of oil-rich regions of Syria. The militiamen were described as “moderate rebels”;

they are jihadists practicing terrorism, with thousands of foreigners among them. Bashar al-Assad was described as unpopular;

he was re-elected in 2014 in a landslide. The voting behaviour of Syrian refugees in Lebanon was telling; far from possible control by Syrian authorities, they cast their ballots overwhelmingly in favour of the Syrian government, confounding those who assumed they would condemn it. A genocide was predicted when Aleppo was taken back in December 2016; in fact, the population of the city

rediscovered the social and even the festive life they had been deprived of by the war. The Syrian government was accused of using chemical weapons; but its stockpile was destroyed in 2013 under the aegis of the United States,

while the jihadists kept theirs.

Listening or gagging?

Any position must be accepted or rejected on its merits, not by defamation or denial of speech. Attendees at the conference had the right attitude. They came in large numbers to judge for themselves. As for the academic world, it is based on certain fundamental principles, such as the examination of a diversity of analyses in order to evaluate them and reach conclusions, and a critical approach toward everything. That is the bedrock of the quest for knowledge which is the mission of universities. Such a fact is not necessarily to the liking of certain economic, political or ideological interests, which may seek to muzzle, mislead

or spook academics in order to hinder free thought and to dissuade the very people whose function is to defend it.

That the Syrian regime has been authoritarian or that it has committed abuses is not in doubt. It is far from perfect. Like all peoples in the Middle East and elsewhere, the Syrian people want change. But it is up to them to determine what those changes will be, not to foreign governments acting by means of armed jihadist militias.

Those who lied about the war against Iraq in 2003

are the same people who disseminate the official narrative on Syria. One must have a short memory to believe them. Critics who have gone against the tide have often been right in past wars. They

often anticipate what history will later confirm. Their input must therefore be taken into account, while the right to question what they say must be preserved. Beeley is one of those voices challenging official truths. She does not claim to be infallible, but she does reveal aspects of the war in Syria that few observers see or analyze. She should be heard and not censored,

always with a critical mind.

Samir Saul is a professor of history at the Université de Montréal. His centres of interest concern France and the Arab World. His investigations focus on the relations between the political and economic dimensions on the international front. In economic history, he studies capital flows, international trade and the history of industries. He is a founding member and coordinator for the Groupement interuniversitaire pour l’histoire des relations internationales (GIHRIC).

Rachad Antonius is a Professor of Sociology at the Université du Québec à Montréal. Born in Cairo, Egypt, he graduated with a B.Sc. (Hons) in Pure and Applied Mathematics from Cairo University. He completed a M.Sc. degree in Mathematics at the University of Manitoba, then a Ph.D. in Sociology at the Universite du Quebec at Montreal. He teaches quantitative methods and research methodology, and he also specializes in migration studies, and Middle-Eastern studies.

Simply an amazing transformation!

Simply an amazing transformation!

}

}