You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Electric driverless cars?

- Thread starter goodiepete

- Start date

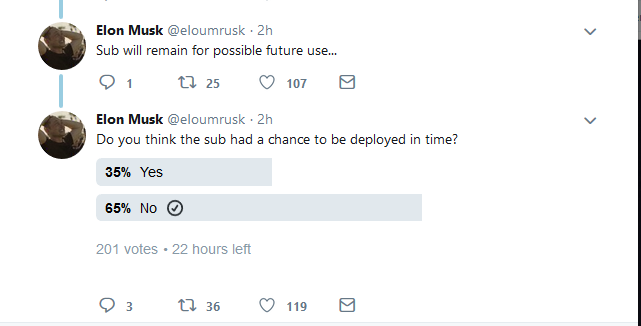

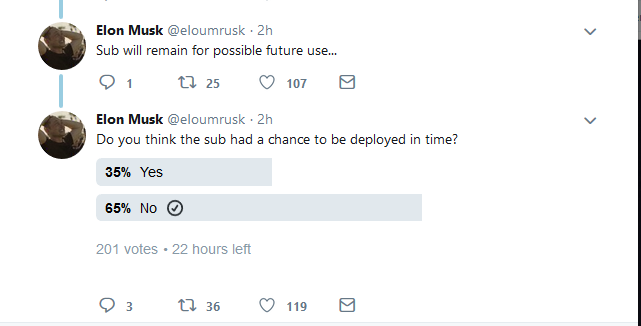

Elon Musk Is Furious Over His Minisub Failure To Participate In Rescue Operation In Northern Thailand

Tesla Plots Bold China Factory Move, Stays Silent on Cost

Updated on July 11, 2018, 6:41 AM GMT+2 Video / 02:41

Baird says big question for investors is how it’ll be paid for

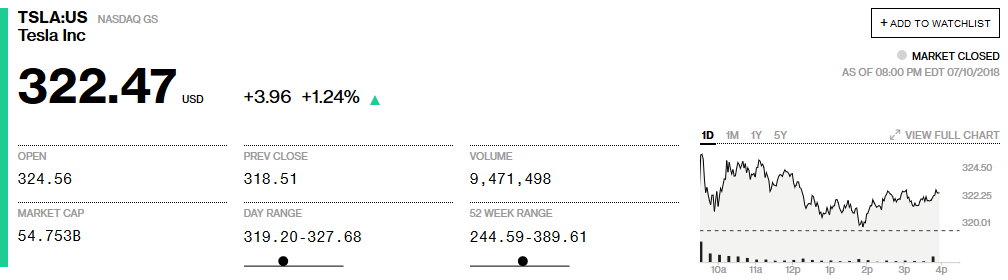

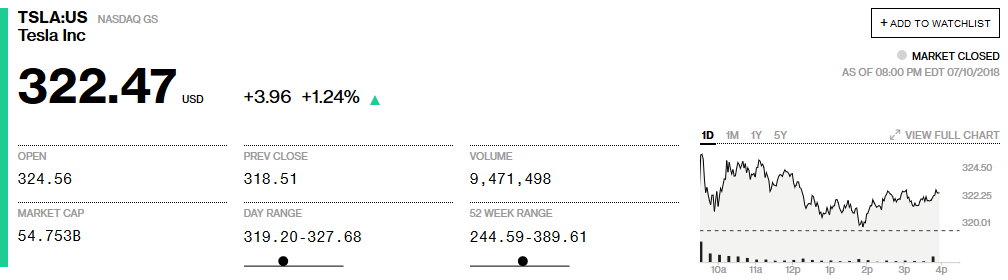

TSLA:US NASDAQ GSn Tesla Inc

Tesla Plots Bold China Factory Move, Stays Silent on Cost

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-07-10/tesla-is-said-to-plan-china-plant-with-500-000-vehicle-capacityUpdated on July 11, 2018, 6:41 AM GMT+2 Video / 02:41

Baird says big question for investors is how it’ll be paid for

TSLA:US NASDAQ GSn Tesla Inc

Hell for Elon Musk Is a Midsize Sedan

July 12, 2018, 11:00 AM GMT+2

Will the Model 3 make Tesla a real car company?

On July 1, Elon Musk went home to sleep. The chief executive of Tesla Inc. had been camping out at his electric car factory in Fremont, Calif., for much of the past week. He’d been sleeping on a couch, or under a desk, as part of a companywide push to get out of what he calls “production hell” by manufacturing at least 5,000 of Tesla’s new Model 3 sedans in a week.

“I was wearing the same clothes for five days,” Musk says in an interview with Bloomberg Businessweek. “My credibility, the credibility of the whole team,” was at stake.

Musk initially promised as many as 200,000 Model 3s by the end of 2017. To get there he planned an unprecedented investment in factory robots, calling the production line “the machine that builds the machine.” He’d said it would look like “alien dreadnought”—a manufacturing process so futuristic, unstoppable, and cost-effective that it would seem extraterrestrial.

It hasn’t worked out that way. Tesla ended 2017 having made not quite 2,700 Model 3s. As of the end of June it had turned out about 41,000, and some analysts express doubts about whether it will ever be able to show a profit on the car, and Tesla hasn’t even started selling the $35,000 base model.

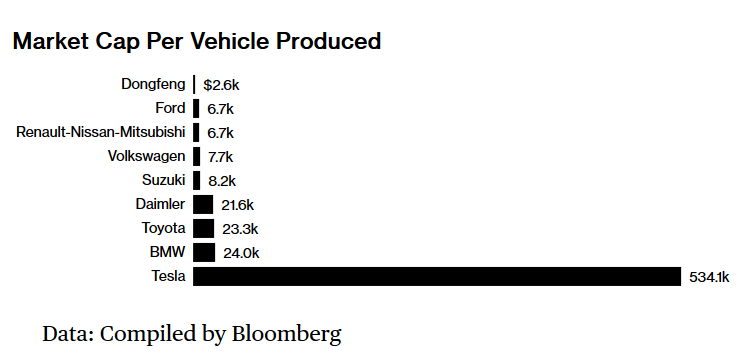

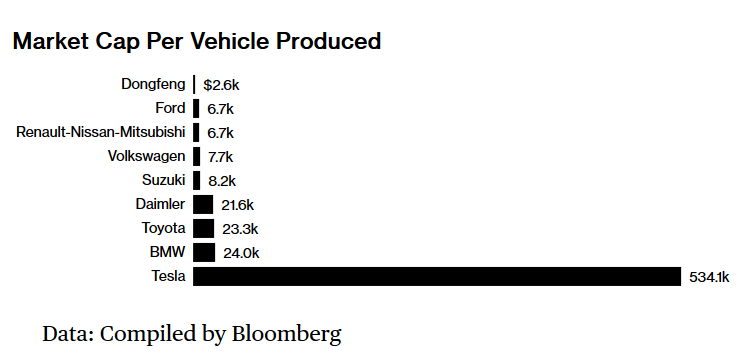

Making matters worse, Tesla has $10 billion in debt and suffered a credit downgrade in March. It’s spent about a billion dollars more per quarter, on average, than it has taken in over the past year, and the cost of a recently announced factory in China is still unknown. Tesla is running out of cash at a time when competition is heating up—Volkswagen, BMW, Daimler, and others plan to release dozens of electric car models.

In early June, at Tesla’s annual meeting, Musk tried to project calm, but at times seemed close to tears. “This is like—I tell you—the most excruciatingly hellish several months that I have ever had,” he said, before noting that Tesla’s assembly lines were being further upgraded, making the company “very likely” to hit the weekly goal of 5,000. He also revealed he’d asked employees to build a third general assembly line that would be “dramatically better than Lines 1 and 2.” That sounded even more alien-dreadnoughty.

A week later, Musk posted a picture of the new facility on Twitter. There were no fancy robotic systems, nor fixed walls, even—just a large tent outside the factory built from scrap from the other lines. The automotive world winced. “Insanity,” said Max Warburton, an analyst with Sanford C. Bernstein & Co., in an email to Bloomberg News. “I don’t think anyone’s seen anything like this outside of the military trying to service vehicles in a war zone.”

The tent sufficed. “I think we just became a real car company,” Musk wrote in a July 1 email to employees announcing that Tesla had made 5,031 Model 3s the previous week. Even so, it’s unclear whether Musk has put Tesla on a path to lasting greatness or just staved off collapse. The company is the most shorted U.S. stock, and a higher percentage of Wall Street analysts give TSLA a sell rating than for all but one stock on the S&P 500. The story of Tesla’s sprint to release the Model 3, based on interviews with 20 members of Tesla’s design and engineering teams, suppliers, and dozens of current and former workers, is a case study in brilliant design and unbelievable hubris.

The prize for Musk is enormous: If he gets the Model 3 right, he will remake a trillion-dollar industry and do more to reduce carbon emissions than any person on the planet. But it may turn out that mass-producing cars is the one challenge that simply defies him.

In early 2015, Musk convened a meeting of his top engineers in a windowless conference room at the factory. There were 12 people, including experts in batteries, design, chassis, interiors, body, drive systems, safety, and thermodynamics. Musk, who did not attend himself, had gathered them to figure out what the Model 3 would be.

Over the course of the meeting, the engineers filled a whiteboard with dozens of requirements, including a range of at least 200 miles and an affordable price. The last of these criteria made the project especially daunting. Even scarier, Tesla would begin selling it in mid-2017, giving the company 2 ½ years to design, test, and build a new vehicle, compared with about five years at a traditional automaker.

Creating a low-cost electric car is about maximizing range in every possible way. For instance, Tesla’s designers added plastic covers, costing $1.50 each, to hide four pads on the underside of the car where a jack goes. The decision reduced wind resistance and improved the car’s range by 3 miles. They also opted for four-piston monoblock caliper brakes, which are usually reserved for more expensive cars. But since the brakes are lightweight, they lower the car’s battery requirements and overall cost. “Every single decision like that was put back into the context of an electric car,” says Doug Field, a former Apple vice president Musk recruited as a top engineer in 2013. In other words, electric cars require new ways of thinking about cost and performance.

Musk decreed that the Model 3 would have a single central screen for all controls and information, which would both cut costs and allow Tesla to push the front seats forward to allow for more rear legroom. Tesla’s design chief, Franz von Holzhausen, spent the 2015 Christmas holiday figuring out how to design a car interior without a traditional dashboard.

Musk declared he didn’t want visible air vents. “I don’t want to see any holes,” von Holzhausen recalls him saying. Von Holzhausen paired engineer Joseph Mardall with designer Peter Blades to figure that one out. Blades’s sketch called for a recessed gap across the entire width of the car from which the air would flow, with a long strip of wood instead of the dash. Mardall pointed out that to make the approach work, the entire ventilation system would need to be redesigned. “Are we serious about this?” he recalls asking.

Musk was serious, but a second problem soon appeared: The wooden strip, just below the air gap, worked like an airplane wing, sucking cold air down and shooting it into the driver’s lap. Mardall, an aerodynamics specialist, proposed adding a second, hidden gap from which air would shoot straight up, lifting the main blast of cold air above the piece of wood and away from the driver’s crotch. “It was one of those eureka moments,” Blades recalls, still in awe of the elegance of the solution. “The spine still tingles.”

The system Blades and Mardall designed combines all the components of a standard HVAC system into a single basketball-size glob of molded plastic tucked under the hood, which Tesla calls the Superbottle. The glob is stamped with a logo of a bottle wearing a superhero cape.

Blades and Mardall relay all this with pride. “I had to negotiate with my wife: I’m going to do seven days a week for the next half-year,” Blades recalls. “And that’s not just me—everybody’s wives or partners—it’s just part of the story of Tesla. At this company if you don’t ask those silly questions and ask to do something crazy, then it’s not really the right place for you.”

If such loyalty seems extreme, it’s partly the result of Musk’s reputation for defying odds (and, some would say, common sense). He was mocked in 2002 when, as a 31-year-old software entrepreneur with no aerospace training, he founded SpaceX. It now launches more rockets a year than any other company.

Mass-producing a car isn’t rocket science; in some ways, it’s harder. Rockets can essentially be built and checked by hand; a perfect car must come off the production line every minute or so if you have any prayer of keeping pace with the world’s leading manufacturers. Cars are composed of tens of thousands of individual parts and have to withstand snow, potholes, and highway speeds, performing flawlessly for years. They are the largest purchase most people make besides a home, and they’re also heavily regulated lethal weapons that contribute to more than a million deaths each year.

At a typical plant run by Toyota Motor Corp., widely seen as the most capable carmaker, a new car requires about 30 hours of labor. Even with all the robots, Tesla spends more than three times that number of hours on each car, says Michelle Hill, a manufacturing expert at management consulting firm Oliver Wyman. And Toyota would never, as Musk has, try a new manufacturing system and all-new workforce on a never-before-built car. Successful carmaking is “the orchestration of so many things that have to play together in unison,” she says.

Musk’s disregard for precedent, of course, is part of his appeal. In the weeks before the March 2016 public unveiling of the Model 3 design, employees took bets on how many prospective buyers would pay a refundable $1,000 deposit to reserve one. The most optimistic prediction was around 200,000; the actual number was twice that. Field recalls opening his staff meeting the following week with a warning: “You are now working at a different company,” he said. “Everything has changed.”

According to one supplier, Tesla had said it expected to spend 28 months to reach large-scale mass production, but after seeing demand for the car, Tesla moved up the timeline by 15 months. It had previously said it would build 500,000 cars per year by 2020, a goal skeptics called outlandish. But in May 2016, Musk said the plan was to do that in 2018.

In an unconventional move, Musk restructured Tesla, assigning the engineers who designed the Model 3 to invent its manufacturing process. He put Field in charge of the factory and gave him the budget to automate as much of the car assembly as possible. Tesla bought two robotics companies, Grohmann Engineering in Germany and Perbix in Minnesota. Field’s team invented dozens of industrial processes. One involved a tool called the golden wheel, an apparatus that automatically breaks in suspensions and aligns cars in one step without humans.

Automakers generally rely on thousands of suppliers, from windshield wiper makers to electronics manufacturers. But Musk has long argued that the traditional supplier model led to cost overruns and mediocrity. Starting in 2015, he told employees he wanted to make even the thorniest parts of his supply chain in-house. In late 2015 he appointed a recently hired car interiors expert, Steve MacManus, to build a seat factory near the main plant in Fremont. Seat assembly is labor-intensive and is outsourced by every major car company to the lowest-paid workers they can find. “Your job is to get us out of seat hell,” MacManus recalls Musk telling him during their first conversation after he’d started.

And so, in one area of MacManus’s Model 3 seat line, more than a dozen robots rapidly piece together the front seats, including tiny motors, hinges, heaters, and frames. Tesla claims this is the world’s first front seat assembly line in which no humans are involved at all. The plan is eventually to use Musk’s tunnel-digging venture, the Boring Co., to dig an underground passageway to bring seats to and from the main Fremont factory, about 2 miles away. They already have a spot in mind.

Musk keeps trying to bring other parts of Tesla’s supply chain in-house. In an email to employees this spring, he also announced he would fire all contractors and consultants unless a Tesla employee personally vouched for them. “We’re going to scrub the barnacles,” he said during the company’s earnings call in May. “It’s pretty crazy. We’ve got barnacles on barnacles. So there’s going to be a lot of barnacle removal.”

To critics, Musk’s description of contractors as parasitic crustaceans is revealing. He is maniacally committed to Tesla’s mission of saving the world from global warming, but at times Tesla has seemed to fall short of more prosaic obligations, such as making sure its workers are safe. On Nov. 18, 2016, eight months before Model 3 production began, a factory employee heard a scream coming from just outside the main building at the Fremont plant. He saw a colleague, quality-control lead Robert Limon, writhing on the blacktop and grabbing at his leg, which was “bleeding like crazy,” the worker says. The specifics of this incident haven’t been previously reported.

Limon’s co-workers gathered around him. Someone used a belt to tie a tourniquet around his leg. The witness, who declined to be named out of concern for adverse consequences from Tesla, says management offered counseling for people who had seen what happened—and the witness took the company up on it, because it was traumatic.

Limon later told this co-worker he’d been hit by a forklift driver who’d been doing doughnuts on the property for fun. Limon didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story, but according to people who saw and spoke to him in the following days, and as depicted in photos seen by Bloomberg Businessweek, the injured leg was amputated.

Tesla says that both Limon and the forklift driver were fooling around in an inappropriate way that isn’t representative of the automaker’s safety culture. Afterward, Tesla says it fired the driver and held factorywide safety meetings on each shift. The company suggests Tesla’s enemies disclosed the episode to damage its reputation. “Nothing is more important to us than the safety of our employees,” a spokesperson says. “This is not to say that there aren’t real issues that need to be dealt with at Tesla or that we’ve made no mistakes with any of the 40,000 people who work at our company.” The spokesperson says Tesla’s goal is to “have the safest factory in the world by far.”

The state agency Cal/OSHA, which fined Tesla $800 in connection with the injury, described it as an ankle fracture. But agency documents show it did not interview Limon. Tesla says it tried repeatedly to arrange an interview. A few months later, Justine White, a Tesla safety official, sent a resignation letter to Musk that was recently reported by the Center for Investigative Reporting. White said she had made “repeated safety recommendations” about “informing employees of forklift hazards in a timely manner after an employee’s lower leg was amputated when run-over.” Tesla disputed White’s claims.

Dozens of current and former Fremont workers, many of whom requested anonymity, say there’s a larger pattern in which a company hellbent on making lots of cars tolerates unsafe conditions. A 2017 analysis by Worksafe Inc., a nonprofit, said that serious injuries at Tesla’s plant in 2015 and 2016 were well above industry averages. Tesla, which is a nonunion company that has been targeted by the United Auto Workers, points out that Worksafe has ties to labor. It says injury rates in 2017 fell 25 percent and were about the same as the industry average. In June, Musk said Tesla’s 2018 injury rates so far were 6 percent below the average, even as Model 3 production increased.

Tesla’s safety records were questioned again earlier this year when the Center for Investigative Reporting reported that Tesla had misclassified work-related injuries as personal medical issues, which made the plant seem safer than it is. Tesla argued that the report was “an ideologically motivated attack by an extremist organization,” but it retroactively added 13 injuries from 2017 to its safety logs, according to a subsequent article. Tesla says it routinely updates safety logs to ensure accuracy.

“An important error that Tesla has made is simply ignoring the extensive experience of the last 50 years in the auto industry,” says Harley Shaiken, a University of California at Berkeley professor who chaired a state commission that warned against the 2010 closure of the Fremont plant, which previously had been operated by Toyota and General Motors Co. as a joint venture. Tesla sought, Shaiken continues, “to start from scratch in a way that has resulted in meltdowns and near-meltdowns.”

Tesla says automation on the Model 3 line is making the factory safer. But when robots break down, employees have to pick up the slack. For instance, an enormously complex robotic conveyance system for bringing parts to the line had to be removed, and teams of human workers wound up doing the work. (Parts of the conveyance system, which had included 500 machines to lift parts, were used to build the new manual production line under the tent.)

Today, Tesla has about 10,000 workers at its Fremont plant. GM and Toyota had less than half that and produced more than 400,000 cars at the plant’s peak in 2006. Tesla argues that a larger workforce is justified given that more of the car is manufactured in-house, but interviews with workers suggest the company has stretched to ensure that there are enough workers on the floor. Current and former employees describe 12-hour shifts as common, with some going as long as 16 hours.

To battle exhaustion, employees drink copious amounts of Red Bull, sometimes provided free by Tesla. New employees develop what’s known as the “Tesla stare.” “They come in vibrant, energized,” says Mikey Catura, a Tesla production associate. “And then a couple weeks go by, and you’ll see them walking out of the building just staring out into space like zombies.”

Four current employees say the pressure they felt to avoid delays forced them to walk through raw sewage when it spilled onto the floor. Dennis Duran, who works in the paint shop, says that one time when workers balked, he and his peers were told, “Just walk through it. We have to keep the line going.” Tesla says it’s not aware of managers telling employees to walk through sewage and that plumbing issues have been handled promptly. It also notes that Duran and Catura have publicly supported unionization efforts at Tesla.

Musk and many Tesla employees dispute that workers are unhappy or unsafe. “There’s always going to be challenges from a safety standpoint and from a production standpoint—that’s all manufacturing,” says Dexter Siga, who started as a technician in 2011 and is now a manager. He adds that Tesla has “had our fair share of challenges” as a young and rapidly growing company, but it treats safety as “an overriding priority.”

For his part, Musk says Tesla demands hard work, but that’s because it’s the only way to survive as a U.S. car manufacturer. “I feel like I have a great debt to the people of Tesla,” he says, his voice cracking with emotion. “The reason I slept on the floor was not because I couldn’t go across the road and be at a hotel. It was because I wanted my circumstances to be worse than anyone else at the company. Whenever they felt pain, I wanted mine to be worse.

“You know,” he continues, “at GM they’ve got a special elevator for executives so they don’t have to mingle with anyone else.” (“Typical Elon, deflecting from the real issue, which is the ability to mass-produce at scale and with quality,” says GM spokesman Ray Wert.) “My desk is the smallest in the factory, and I am barely there,” he says. “The reason people in the paint shop were working their asses off was because I was with them. I’m not in some ivory tower.”

In July 2017, Musk delivered the first Model 3 sedans at a raucous party in Fremont. The car was celebrated by reviewers (“Driving Tesla’s Model 3 Changes Everything” was Bloomberg’s take), but it was almost immediately apparent that Tesla could never deliver it in the numbers Musk promised.

The first problem involved the batteries. Tesla and Panasonic Corp., which jointly operate a battery factory in Nevada, had designed cells that were slightly larger than the standard 18650 cells used in previous Teslas. The new batteries were better, but the automated manufacturing line for packing thousands of them together didn’t work, and the task had to be done by hand for a time. A new system, made by Grohmann, was eventually built and flown in.

In November, Musk told analysts he was “really depressed” but doing his best to fix the battery-packing issue. Other problems emerged, and Tesla had to shut down the Fremont plant for five days in February. In retrospect, Musk says, trying to automate so much of Tesla’s factory at once was overly ambitious. “We thought it would be good, but it was not good,” he says. “We were huge idiots and didn’t know what we were doing.”

This April, Musk took over manufacturing engineering personally. “I’m back to sleeping at factory,” he tweeted. “Car biz is hell.” Field, who’d been in charge of the factory, took a leave of absence the following month; he later left the company. In mid-June, Tesla announced it was laying off 9 percent of its workforce, more than 3,000 people.

Musk turned 47 in late June, during the final sprint to make 5,000 cars a week. “First bday I’ve spent in the factory,” he tweeted, “but it’s somehow the best.” On the Friday before the deadline, Musk seemed giddy with excitement about what he expected would be a spike in Tesla’s stock price. He tweeted a music video of the 1958 single Short Shorts, by the Royal Teens. On Sunday he announced that Tesla had hit the milestone and proclaimed his love for his employees. Tesla’s stock price gained 5 percent on Monday morning.

The exuberance was gone by lunchtime, and Tesla’s stock finished the day down 2 percent. It lost 7 percent on Tuesday. The “short burn of the century” that Musk had predicted had failed to come to pass, as skeptics pointed out that Tesla’s wild sprint would be unsustainable.

Musk projected confidence during an interview with Businessweek on July 8. “The past year has been very difficult, but I feel like the coming year is going to be really quite good,” he said. He still had “one foot in hell.” He said manufacturing hell will be over in a month.

At present, the Model 3 is selling more units in the U.S. than any comparably priced midsize sedan, including those offered by Mercedes-Benz, BMW, and Audi. It’s fast and fun to drive. When you stomp the accelerator, the Model 3 stomps back, and Tesla’s designers tried to replicate the feeling of instantaneous acceleration in every aspect of the driving experience. “Point and shoot,” says Lars Moravy, Tesla’s director of chassis dynamics. “There’s no overshoot, and there’s no delay. That’s the essence of the electric motor and our name.”

Of course, quick acceleration isn’t unique to the Model 3; it’s true of all electric cars. But the fact that there even is a market for these vehicles is to a large extent Musk’s doing. He set out to teach the world that consumers would pay for zero-emissions cars in huge numbers. Whatever happens to Tesla, he’s succeeded in that. Tesla is, as Musk says, “a real car company.” That’s glorious, and it’s also hell. —With Sohee Kim

Next:

Inside Tesla’s Model 3 Factory

Bloomberg Built Its Own Model to Estimate Tesla’s Output of the Model 3

‘The Last Bet-the-Company Situation’: Q&A With Elon Musk

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2018-07-12/how-tesla-s-model-3-became-elon-musk-s-version-of-hellJuly 12, 2018, 11:00 AM GMT+2

Will the Model 3 make Tesla a real car company?

On July 1, Elon Musk went home to sleep. The chief executive of Tesla Inc. had been camping out at his electric car factory in Fremont, Calif., for much of the past week. He’d been sleeping on a couch, or under a desk, as part of a companywide push to get out of what he calls “production hell” by manufacturing at least 5,000 of Tesla’s new Model 3 sedans in a week.

“I was wearing the same clothes for five days,” Musk says in an interview with Bloomberg Businessweek. “My credibility, the credibility of the whole team,” was at stake.

Musk initially promised as many as 200,000 Model 3s by the end of 2017. To get there he planned an unprecedented investment in factory robots, calling the production line “the machine that builds the machine.” He’d said it would look like “alien dreadnought”—a manufacturing process so futuristic, unstoppable, and cost-effective that it would seem extraterrestrial.

It hasn’t worked out that way. Tesla ended 2017 having made not quite 2,700 Model 3s. As of the end of June it had turned out about 41,000, and some analysts express doubts about whether it will ever be able to show a profit on the car, and Tesla hasn’t even started selling the $35,000 base model.

Making matters worse, Tesla has $10 billion in debt and suffered a credit downgrade in March. It’s spent about a billion dollars more per quarter, on average, than it has taken in over the past year, and the cost of a recently announced factory in China is still unknown. Tesla is running out of cash at a time when competition is heating up—Volkswagen, BMW, Daimler, and others plan to release dozens of electric car models.

In early June, at Tesla’s annual meeting, Musk tried to project calm, but at times seemed close to tears. “This is like—I tell you—the most excruciatingly hellish several months that I have ever had,” he said, before noting that Tesla’s assembly lines were being further upgraded, making the company “very likely” to hit the weekly goal of 5,000. He also revealed he’d asked employees to build a third general assembly line that would be “dramatically better than Lines 1 and 2.” That sounded even more alien-dreadnoughty.

A week later, Musk posted a picture of the new facility on Twitter. There were no fancy robotic systems, nor fixed walls, even—just a large tent outside the factory built from scrap from the other lines. The automotive world winced. “Insanity,” said Max Warburton, an analyst with Sanford C. Bernstein & Co., in an email to Bloomberg News. “I don’t think anyone’s seen anything like this outside of the military trying to service vehicles in a war zone.”

The tent sufficed. “I think we just became a real car company,” Musk wrote in a July 1 email to employees announcing that Tesla had made 5,031 Model 3s the previous week. Even so, it’s unclear whether Musk has put Tesla on a path to lasting greatness or just staved off collapse. The company is the most shorted U.S. stock, and a higher percentage of Wall Street analysts give TSLA a sell rating than for all but one stock on the S&P 500. The story of Tesla’s sprint to release the Model 3, based on interviews with 20 members of Tesla’s design and engineering teams, suppliers, and dozens of current and former workers, is a case study in brilliant design and unbelievable hubris.

The prize for Musk is enormous: If he gets the Model 3 right, he will remake a trillion-dollar industry and do more to reduce carbon emissions than any person on the planet. But it may turn out that mass-producing cars is the one challenge that simply defies him.

In early 2015, Musk convened a meeting of his top engineers in a windowless conference room at the factory. There were 12 people, including experts in batteries, design, chassis, interiors, body, drive systems, safety, and thermodynamics. Musk, who did not attend himself, had gathered them to figure out what the Model 3 would be.

Over the course of the meeting, the engineers filled a whiteboard with dozens of requirements, including a range of at least 200 miles and an affordable price. The last of these criteria made the project especially daunting. Even scarier, Tesla would begin selling it in mid-2017, giving the company 2 ½ years to design, test, and build a new vehicle, compared with about five years at a traditional automaker.

Creating a low-cost electric car is about maximizing range in every possible way. For instance, Tesla’s designers added plastic covers, costing $1.50 each, to hide four pads on the underside of the car where a jack goes. The decision reduced wind resistance and improved the car’s range by 3 miles. They also opted for four-piston monoblock caliper brakes, which are usually reserved for more expensive cars. But since the brakes are lightweight, they lower the car’s battery requirements and overall cost. “Every single decision like that was put back into the context of an electric car,” says Doug Field, a former Apple vice president Musk recruited as a top engineer in 2013. In other words, electric cars require new ways of thinking about cost and performance.

Musk decreed that the Model 3 would have a single central screen for all controls and information, which would both cut costs and allow Tesla to push the front seats forward to allow for more rear legroom. Tesla’s design chief, Franz von Holzhausen, spent the 2015 Christmas holiday figuring out how to design a car interior without a traditional dashboard.

Musk declared he didn’t want visible air vents. “I don’t want to see any holes,” von Holzhausen recalls him saying. Von Holzhausen paired engineer Joseph Mardall with designer Peter Blades to figure that one out. Blades’s sketch called for a recessed gap across the entire width of the car from which the air would flow, with a long strip of wood instead of the dash. Mardall pointed out that to make the approach work, the entire ventilation system would need to be redesigned. “Are we serious about this?” he recalls asking.

Musk was serious, but a second problem soon appeared: The wooden strip, just below the air gap, worked like an airplane wing, sucking cold air down and shooting it into the driver’s lap. Mardall, an aerodynamics specialist, proposed adding a second, hidden gap from which air would shoot straight up, lifting the main blast of cold air above the piece of wood and away from the driver’s crotch. “It was one of those eureka moments,” Blades recalls, still in awe of the elegance of the solution. “The spine still tingles.”

The system Blades and Mardall designed combines all the components of a standard HVAC system into a single basketball-size glob of molded plastic tucked under the hood, which Tesla calls the Superbottle. The glob is stamped with a logo of a bottle wearing a superhero cape.

Blades and Mardall relay all this with pride. “I had to negotiate with my wife: I’m going to do seven days a week for the next half-year,” Blades recalls. “And that’s not just me—everybody’s wives or partners—it’s just part of the story of Tesla. At this company if you don’t ask those silly questions and ask to do something crazy, then it’s not really the right place for you.”

If such loyalty seems extreme, it’s partly the result of Musk’s reputation for defying odds (and, some would say, common sense). He was mocked in 2002 when, as a 31-year-old software entrepreneur with no aerospace training, he founded SpaceX. It now launches more rockets a year than any other company.

Mass-producing a car isn’t rocket science; in some ways, it’s harder. Rockets can essentially be built and checked by hand; a perfect car must come off the production line every minute or so if you have any prayer of keeping pace with the world’s leading manufacturers. Cars are composed of tens of thousands of individual parts and have to withstand snow, potholes, and highway speeds, performing flawlessly for years. They are the largest purchase most people make besides a home, and they’re also heavily regulated lethal weapons that contribute to more than a million deaths each year.

At a typical plant run by Toyota Motor Corp., widely seen as the most capable carmaker, a new car requires about 30 hours of labor. Even with all the robots, Tesla spends more than three times that number of hours on each car, says Michelle Hill, a manufacturing expert at management consulting firm Oliver Wyman. And Toyota would never, as Musk has, try a new manufacturing system and all-new workforce on a never-before-built car. Successful carmaking is “the orchestration of so many things that have to play together in unison,” she says.

Musk’s disregard for precedent, of course, is part of his appeal. In the weeks before the March 2016 public unveiling of the Model 3 design, employees took bets on how many prospective buyers would pay a refundable $1,000 deposit to reserve one. The most optimistic prediction was around 200,000; the actual number was twice that. Field recalls opening his staff meeting the following week with a warning: “You are now working at a different company,” he said. “Everything has changed.”

According to one supplier, Tesla had said it expected to spend 28 months to reach large-scale mass production, but after seeing demand for the car, Tesla moved up the timeline by 15 months. It had previously said it would build 500,000 cars per year by 2020, a goal skeptics called outlandish. But in May 2016, Musk said the plan was to do that in 2018.

In an unconventional move, Musk restructured Tesla, assigning the engineers who designed the Model 3 to invent its manufacturing process. He put Field in charge of the factory and gave him the budget to automate as much of the car assembly as possible. Tesla bought two robotics companies, Grohmann Engineering in Germany and Perbix in Minnesota. Field’s team invented dozens of industrial processes. One involved a tool called the golden wheel, an apparatus that automatically breaks in suspensions and aligns cars in one step without humans.

Automakers generally rely on thousands of suppliers, from windshield wiper makers to electronics manufacturers. But Musk has long argued that the traditional supplier model led to cost overruns and mediocrity. Starting in 2015, he told employees he wanted to make even the thorniest parts of his supply chain in-house. In late 2015 he appointed a recently hired car interiors expert, Steve MacManus, to build a seat factory near the main plant in Fremont. Seat assembly is labor-intensive and is outsourced by every major car company to the lowest-paid workers they can find. “Your job is to get us out of seat hell,” MacManus recalls Musk telling him during their first conversation after he’d started.

And so, in one area of MacManus’s Model 3 seat line, more than a dozen robots rapidly piece together the front seats, including tiny motors, hinges, heaters, and frames. Tesla claims this is the world’s first front seat assembly line in which no humans are involved at all. The plan is eventually to use Musk’s tunnel-digging venture, the Boring Co., to dig an underground passageway to bring seats to and from the main Fremont factory, about 2 miles away. They already have a spot in mind.

Musk keeps trying to bring other parts of Tesla’s supply chain in-house. In an email to employees this spring, he also announced he would fire all contractors and consultants unless a Tesla employee personally vouched for them. “We’re going to scrub the barnacles,” he said during the company’s earnings call in May. “It’s pretty crazy. We’ve got barnacles on barnacles. So there’s going to be a lot of barnacle removal.”

To critics, Musk’s description of contractors as parasitic crustaceans is revealing. He is maniacally committed to Tesla’s mission of saving the world from global warming, but at times Tesla has seemed to fall short of more prosaic obligations, such as making sure its workers are safe. On Nov. 18, 2016, eight months before Model 3 production began, a factory employee heard a scream coming from just outside the main building at the Fremont plant. He saw a colleague, quality-control lead Robert Limon, writhing on the blacktop and grabbing at his leg, which was “bleeding like crazy,” the worker says. The specifics of this incident haven’t been previously reported.

Limon’s co-workers gathered around him. Someone used a belt to tie a tourniquet around his leg. The witness, who declined to be named out of concern for adverse consequences from Tesla, says management offered counseling for people who had seen what happened—and the witness took the company up on it, because it was traumatic.

Limon later told this co-worker he’d been hit by a forklift driver who’d been doing doughnuts on the property for fun. Limon didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story, but according to people who saw and spoke to him in the following days, and as depicted in photos seen by Bloomberg Businessweek, the injured leg was amputated.

Tesla says that both Limon and the forklift driver were fooling around in an inappropriate way that isn’t representative of the automaker’s safety culture. Afterward, Tesla says it fired the driver and held factorywide safety meetings on each shift. The company suggests Tesla’s enemies disclosed the episode to damage its reputation. “Nothing is more important to us than the safety of our employees,” a spokesperson says. “This is not to say that there aren’t real issues that need to be dealt with at Tesla or that we’ve made no mistakes with any of the 40,000 people who work at our company.” The spokesperson says Tesla’s goal is to “have the safest factory in the world by far.”

The state agency Cal/OSHA, which fined Tesla $800 in connection with the injury, described it as an ankle fracture. But agency documents show it did not interview Limon. Tesla says it tried repeatedly to arrange an interview. A few months later, Justine White, a Tesla safety official, sent a resignation letter to Musk that was recently reported by the Center for Investigative Reporting. White said she had made “repeated safety recommendations” about “informing employees of forklift hazards in a timely manner after an employee’s lower leg was amputated when run-over.” Tesla disputed White’s claims.

Dozens of current and former Fremont workers, many of whom requested anonymity, say there’s a larger pattern in which a company hellbent on making lots of cars tolerates unsafe conditions. A 2017 analysis by Worksafe Inc., a nonprofit, said that serious injuries at Tesla’s plant in 2015 and 2016 were well above industry averages. Tesla, which is a nonunion company that has been targeted by the United Auto Workers, points out that Worksafe has ties to labor. It says injury rates in 2017 fell 25 percent and were about the same as the industry average. In June, Musk said Tesla’s 2018 injury rates so far were 6 percent below the average, even as Model 3 production increased.

Tesla’s safety records were questioned again earlier this year when the Center for Investigative Reporting reported that Tesla had misclassified work-related injuries as personal medical issues, which made the plant seem safer than it is. Tesla argued that the report was “an ideologically motivated attack by an extremist organization,” but it retroactively added 13 injuries from 2017 to its safety logs, according to a subsequent article. Tesla says it routinely updates safety logs to ensure accuracy.

“An important error that Tesla has made is simply ignoring the extensive experience of the last 50 years in the auto industry,” says Harley Shaiken, a University of California at Berkeley professor who chaired a state commission that warned against the 2010 closure of the Fremont plant, which previously had been operated by Toyota and General Motors Co. as a joint venture. Tesla sought, Shaiken continues, “to start from scratch in a way that has resulted in meltdowns and near-meltdowns.”

Tesla says automation on the Model 3 line is making the factory safer. But when robots break down, employees have to pick up the slack. For instance, an enormously complex robotic conveyance system for bringing parts to the line had to be removed, and teams of human workers wound up doing the work. (Parts of the conveyance system, which had included 500 machines to lift parts, were used to build the new manual production line under the tent.)

Today, Tesla has about 10,000 workers at its Fremont plant. GM and Toyota had less than half that and produced more than 400,000 cars at the plant’s peak in 2006. Tesla argues that a larger workforce is justified given that more of the car is manufactured in-house, but interviews with workers suggest the company has stretched to ensure that there are enough workers on the floor. Current and former employees describe 12-hour shifts as common, with some going as long as 16 hours.

To battle exhaustion, employees drink copious amounts of Red Bull, sometimes provided free by Tesla. New employees develop what’s known as the “Tesla stare.” “They come in vibrant, energized,” says Mikey Catura, a Tesla production associate. “And then a couple weeks go by, and you’ll see them walking out of the building just staring out into space like zombies.”

Four current employees say the pressure they felt to avoid delays forced them to walk through raw sewage when it spilled onto the floor. Dennis Duran, who works in the paint shop, says that one time when workers balked, he and his peers were told, “Just walk through it. We have to keep the line going.” Tesla says it’s not aware of managers telling employees to walk through sewage and that plumbing issues have been handled promptly. It also notes that Duran and Catura have publicly supported unionization efforts at Tesla.

Musk and many Tesla employees dispute that workers are unhappy or unsafe. “There’s always going to be challenges from a safety standpoint and from a production standpoint—that’s all manufacturing,” says Dexter Siga, who started as a technician in 2011 and is now a manager. He adds that Tesla has “had our fair share of challenges” as a young and rapidly growing company, but it treats safety as “an overriding priority.”

For his part, Musk says Tesla demands hard work, but that’s because it’s the only way to survive as a U.S. car manufacturer. “I feel like I have a great debt to the people of Tesla,” he says, his voice cracking with emotion. “The reason I slept on the floor was not because I couldn’t go across the road and be at a hotel. It was because I wanted my circumstances to be worse than anyone else at the company. Whenever they felt pain, I wanted mine to be worse.

“You know,” he continues, “at GM they’ve got a special elevator for executives so they don’t have to mingle with anyone else.” (“Typical Elon, deflecting from the real issue, which is the ability to mass-produce at scale and with quality,” says GM spokesman Ray Wert.) “My desk is the smallest in the factory, and I am barely there,” he says. “The reason people in the paint shop were working their asses off was because I was with them. I’m not in some ivory tower.”

In July 2017, Musk delivered the first Model 3 sedans at a raucous party in Fremont. The car was celebrated by reviewers (“Driving Tesla’s Model 3 Changes Everything” was Bloomberg’s take), but it was almost immediately apparent that Tesla could never deliver it in the numbers Musk promised.

The first problem involved the batteries. Tesla and Panasonic Corp., which jointly operate a battery factory in Nevada, had designed cells that were slightly larger than the standard 18650 cells used in previous Teslas. The new batteries were better, but the automated manufacturing line for packing thousands of them together didn’t work, and the task had to be done by hand for a time. A new system, made by Grohmann, was eventually built and flown in.

In November, Musk told analysts he was “really depressed” but doing his best to fix the battery-packing issue. Other problems emerged, and Tesla had to shut down the Fremont plant for five days in February. In retrospect, Musk says, trying to automate so much of Tesla’s factory at once was overly ambitious. “We thought it would be good, but it was not good,” he says. “We were huge idiots and didn’t know what we were doing.”

This April, Musk took over manufacturing engineering personally. “I’m back to sleeping at factory,” he tweeted. “Car biz is hell.” Field, who’d been in charge of the factory, took a leave of absence the following month; he later left the company. In mid-June, Tesla announced it was laying off 9 percent of its workforce, more than 3,000 people.

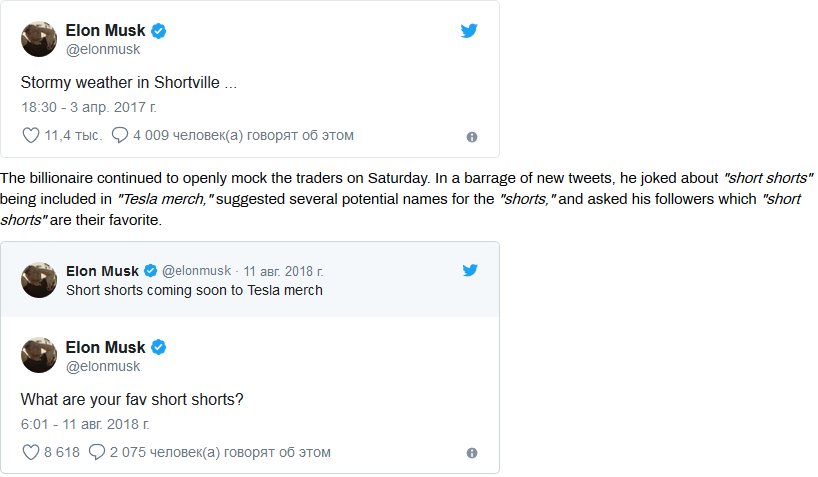

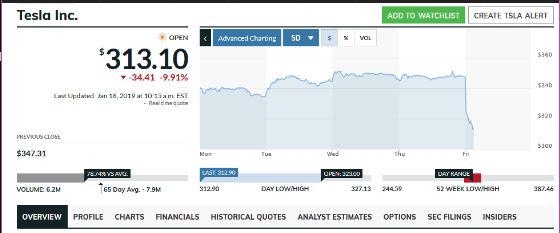

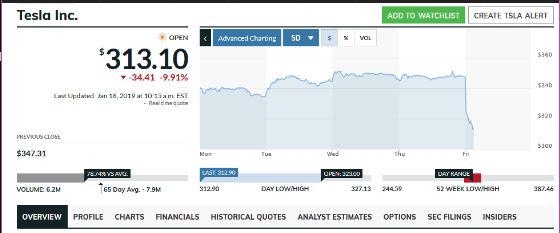

Musk turned 47 in late June, during the final sprint to make 5,000 cars a week. “First bday I’ve spent in the factory,” he tweeted, “but it’s somehow the best.” On the Friday before the deadline, Musk seemed giddy with excitement about what he expected would be a spike in Tesla’s stock price. He tweeted a music video of the 1958 single Short Shorts, by the Royal Teens. On Sunday he announced that Tesla had hit the milestone and proclaimed his love for his employees. Tesla’s stock price gained 5 percent on Monday morning.

The exuberance was gone by lunchtime, and Tesla’s stock finished the day down 2 percent. It lost 7 percent on Tuesday. The “short burn of the century” that Musk had predicted had failed to come to pass, as skeptics pointed out that Tesla’s wild sprint would be unsustainable.

Musk projected confidence during an interview with Businessweek on July 8. “The past year has been very difficult, but I feel like the coming year is going to be really quite good,” he said. He still had “one foot in hell.” He said manufacturing hell will be over in a month.

At present, the Model 3 is selling more units in the U.S. than any comparably priced midsize sedan, including those offered by Mercedes-Benz, BMW, and Audi. It’s fast and fun to drive. When you stomp the accelerator, the Model 3 stomps back, and Tesla’s designers tried to replicate the feeling of instantaneous acceleration in every aspect of the driving experience. “Point and shoot,” says Lars Moravy, Tesla’s director of chassis dynamics. “There’s no overshoot, and there’s no delay. That’s the essence of the electric motor and our name.”

Of course, quick acceleration isn’t unique to the Model 3; it’s true of all electric cars. But the fact that there even is a market for these vehicles is to a large extent Musk’s doing. He set out to teach the world that consumers would pay for zero-emissions cars in huge numbers. Whatever happens to Tesla, he’s succeeded in that. Tesla is, as Musk says, “a real car company.” That’s glorious, and it’s also hell. —With Sohee Kim

Next:

Inside Tesla’s Model 3 Factory

Bloomberg Built Its Own Model to Estimate Tesla’s Output of the Model 3

‘The Last Bet-the-Company Situation’: Q&A With Elon Musk

'Nuclear attack': Investors sue Musk over 'misleading' tweet on making Tesla private

Edited time: 12 Aug, 2018 08:57

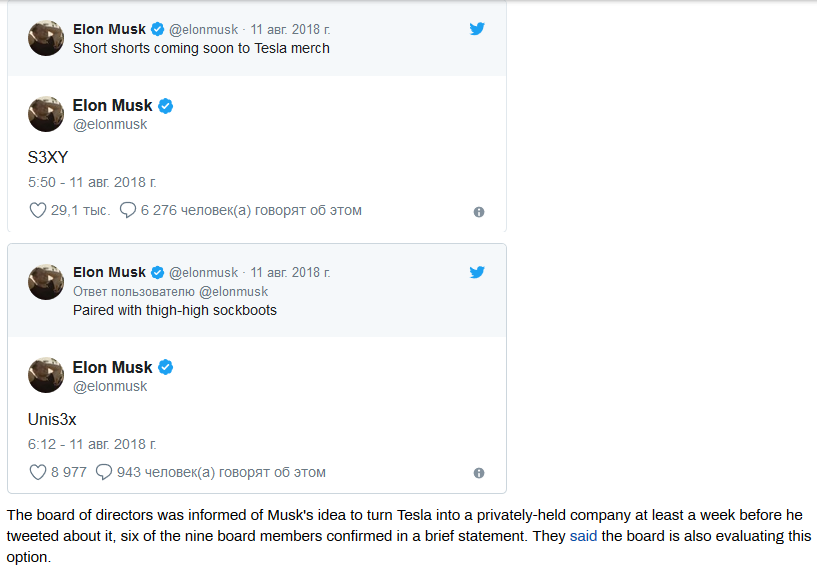

Two investors accuse Elon Musk of manipulating Tesla's share prices by teasing on Twitter that he might pull the company from public markets, and hurting short-sellers. He then took to Twitter to mock them.

Investors argue that the carmaker artificially inflated Tesla's stock price and broke federal securities laws. The lawsuits were filed three days after Musk unexpectedly tweeted to his 22.3 million followers that he is "considering" removing Tesla from public markets, making it a privately-held company.

Tesla's shares did go up by more than 10 percent after the controversial tweet, but the gain was wiped out two days later as the price began to decline.

The tweet surprised many observers and drew criticism that it was not the best way for Musk to announce important decisions. "I do not believe this is the appropriate way to suggest going private," Charles Elson, director of the John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware, told CNBC.

The plaintiffs say Musk's tweet came as a "nuclear attack" brought on to "completely decimate" short-sellers – traders who make money by borrowing overpriced shares, sell them, and then repurchase the shares at a lower price.

The investors also accuse Musk of misleading the shareholders by claiming in the same tweet that he had "secured" the funds for making the company private, while failing to provide any proof of doing so. The US Securities and Trade Commission is now checking whether the tweet was factual, Bloomberg reported, citing its own sources.

Elon Musk has a long history of feuding with short-sellers. He is known for making sarcastic tweets in the past, such as "Stormy weather in Shortville," after reports of Tesla stocks going up.

Sources familiar with the matter confirmed to Bloomberg that Musk and his advisers are seeking investors to back the possible transformation and are holding "early discussions" with banks about the "feasibility" of it.

"A final decision has not yet been made," the Tesla founder said in an email sent to employees.

Musk said he is thinking about pulling Tesla out of the stock market, citing "wild swings" in the company's stock price which can be "a major distraction for everyone working at Tesla." He added that being public "puts enormous pressure" on Tesla, forcing it to make decisions "not necessarily right for the long-term."

The Tesla CEO wrote that he would like to provide the shareholders with two options – staying as investors in Tesla as a privately-held company or selling their stock at $420 per share. "My hope is for all shareholders to remain," Musk said.

Always had the feeling that Tesla was front for some shady operations.

A second former Tesla employee has filed a formal whistleblower complaint with the Securities and Exchange Commission, alleging the automaker failed to disclose to shareholders that law enforcement uncovered an alleged drug trafficking ring involving employees at its Gigafactory plant in Nevada.

Karl Hansen, a former member of Tesla’s internal security department and its investigations division, joins ex-Gigafactory technician Martin Tripp as the second Tesla employee seeking whistleblower status with the SEC. But Hansen’s offering up claims that go far beyond the alleged manufacturing issues highlighted by Tripp.

“I hope that shining a light on Tesla’s practices will cause appropriate governmental action against the company and its management,” Hansen said in a statement.

Tesla didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment. A DEA spokesperson didn’t have an immediate comment when reached by Jalopnik.

A summary of Hansen’s complaint, which was filed Aug. 9, was released Thursday by attorney Stuart Meissner, who’s also representing Tripp. One of the former employee’s most startling claims is that Tesla failed to reveal information sent by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, regarding evidence of “substantial drug trafficking” by Tesla employees at the Gigafactory.

Hansen claims Tesla received a written notification from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration/Storey County Sheriff’s Office Task Force in May, “alleging that several Tesla employees may be participants in a narcotics trafficking ring involving the sale of significant quantities of cocaine and possibly crystal methamphetamine at the Gigafactory on behalf of a Mexican drug cartel from Sonora Mexico.”

Hansen said that he told Tesla on June 12 that he had “corroborated connections between certain Tesla employees at the time and various alleged members of the Mexican drug cartel identified in the DEA report as located in Mexico, that he urged Tesla to disclose his findings to law enforcement and to the DEA task force, but that Tesla refused to do so and instead advised him that Tesla would hire ‘outside vendors’ to further investigate the issue.”

Hansen claims he reported the results to three supervisors, but says that the public nor Tesla’s board of directors were notified of the findings.

A message was left seeking comment with the Storey County sheriff’s office. A spokesperson for the DEA didn’t have an immediate comment when reached by Jalopnik.

Hansen also alleges that he discovered that $37 million of copper and raw materials had been stolen from Tesla’s Gigafactory between January and June. But he claims that he was “instructed not to report the thefts to outside law enforcement” and “that he was directed to cease his internal investigation into the issue,” according to the summary of his claims.

An SEC tip is a formal whistleblower complaint that could lead to Hansen becoming eligible for a financial award, if securities laws violations are confirmed by the agency.

More as we get it.

Meanwhile:

A second former Tesla employee has filed a formal whistleblower complaint with the Securities and Exchange Commission, alleging the automaker failed to disclose to shareholders that law enforcement uncovered an alleged drug trafficking ring involving employees at its Gigafactory plant in Nevada.

Karl Hansen, a former member of Tesla’s internal security department and its investigations division, joins ex-Gigafactory technician Martin Tripp as the second Tesla employee seeking whistleblower status with the SEC. But Hansen’s offering up claims that go far beyond the alleged manufacturing issues highlighted by Tripp.

“I hope that shining a light on Tesla’s practices will cause appropriate governmental action against the company and its management,” Hansen said in a statement.

Tesla didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment. A DEA spokesperson didn’t have an immediate comment when reached by Jalopnik.

A summary of Hansen’s complaint, which was filed Aug. 9, was released Thursday by attorney Stuart Meissner, who’s also representing Tripp. One of the former employee’s most startling claims is that Tesla failed to reveal information sent by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, regarding evidence of “substantial drug trafficking” by Tesla employees at the Gigafactory.

Hansen claims Tesla received a written notification from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration/Storey County Sheriff’s Office Task Force in May, “alleging that several Tesla employees may be participants in a narcotics trafficking ring involving the sale of significant quantities of cocaine and possibly crystal methamphetamine at the Gigafactory on behalf of a Mexican drug cartel from Sonora Mexico.”

Hansen said that he told Tesla on June 12 that he had “corroborated connections between certain Tesla employees at the time and various alleged members of the Mexican drug cartel identified in the DEA report as located in Mexico, that he urged Tesla to disclose his findings to law enforcement and to the DEA task force, but that Tesla refused to do so and instead advised him that Tesla would hire ‘outside vendors’ to further investigate the issue.”

Hansen claims he reported the results to three supervisors, but says that the public nor Tesla’s board of directors were notified of the findings.

A message was left seeking comment with the Storey County sheriff’s office. A spokesperson for the DEA didn’t have an immediate comment when reached by Jalopnik.

Hansen also alleges that he discovered that $37 million of copper and raw materials had been stolen from Tesla’s Gigafactory between January and June. But he claims that he was “instructed not to report the thefts to outside law enforcement” and “that he was directed to cease his internal investigation into the issue,” according to the summary of his claims.

An SEC tip is a formal whistleblower complaint that could lead to Hansen becoming eligible for a financial award, if securities laws violations are confirmed by the agency.

More as we get it.

Meanwhile:

In keeping with their scheme business model of having the cart well in front of the horse, Tesla has just announced that they’re going to begin taking orders for the Model 3 in China. But as a New York Times expose recently pointed out, many of those who ordered Model 3s in the United States - like 44 year old Jim Fyfe - are still being rope-a-doped, misled and confused (if not outright deceived) when it comes to taking delivery of their new cars. For traditional automakers, such behavior would be embarrassing and totally unacceptable. For Tesla, it just seems to be one more thing that the company, stockholders, the Board and cultists customers have not problem tolerating.

Fyfe put down a $2500 deposit in June to order a $70,000 black performance Model 3. He was given a delivery day in early September, but when he tried to go get his car he was told by the company that it was still in California. Two more weeks went by without an update from the company, so he took the initiative and called the delivery center, who then told him his vehicle had been involved in an accident during transit.

In keeping with theirscheme business model of having the cart well in front of the horse, Tesla has just announced that they’re going to begin taking orders for the Model 3 in China. But as a New York Times expose recently pointed out, many of those who ordered Model 3s in the United States - like 44 year old Jim Fyfe - are still being rope-a-doped, misled and confused (if not outright deceived) when it comes to taking delivery of their new cars. For traditional automakers, such behavior would be embarrassing and totally unacceptable. For Tesla, it just seems to be one more thing that the company, stockholders, the Board and cultists customers have not problem tolerating.

Fyfe put down a $2500 deposit in June to order a $70,000 black performance Model 3. He was given a delivery day in early September, but when he tried to go get his car he was told by the company that it was still in California. Two more weeks went by without an update from the company, so he took the initiative and called the delivery center, who then told him his vehicle had been involved in an accident during transit.

After walking to work for two weeks, he then checked in on the status of his new vehicle. Tesla told him that they had one for him but it was still at the Fremont, California factory. In the interim, Tesla rented him a Cadillac to drive and he finally got his Model 3 on October 26.

Another buyer, Jonathan Berent, paid $1000 in 2016 to reserve the right to order a Model 3, then paid an additional $2500 this year as a deposit. In early September, he was told by the company that his car was near a delivery center by the Fremont plant and, after heading there with a check for the balance, he was given a VIN number and shown his car.

While the car was being detailed to be given to him he was told there was a mixup. The car that he was shown was apparently assigned to another customer who shared not the same last name but the same first name. They eventually found another car an hour away and when it arrived, it had paint defects that needed to be repaired. When he decided to cancel his order, he was contacted repeatedly over the coming weeks by sales representatives who told him they had a car ready for him. The company even went so far as to say they would deliver it to his home or to a nearby coffee shop if he wanted.

It's Elon Musk's genius and Tesla's outside the box thinking that have made these embarrassing complications possible, according to Mike Ramsey, a Gartner analyst.

He stated: "Tesla had a huge volume push in the third quarter, and they probably could have avoided a lot of this if they had traditional dealers."

Of course, if Tesla had a traditional dealership network, its cash burn would be orders of magnitude higher and probably would be out of business long ago, and while we doubt that this is what Elon meant when he said he wanted Tesla to be a "disruptor", we are quite confident that as Tesla ramps up production, this is only a glimpse of the first circle of delivery logistics hell" that Elon has warned about.

Flashback: July 17, 2017

Tesla Welcomes Linda Johnson Rice and James Murdoch as New Independent Directors to its Board

Fyfe put down a $2500 deposit in June to order a $70,000 black performance Model 3. He was given a delivery day in early September, but when he tried to go get his car he was told by the company that it was still in California. Two more weeks went by without an update from the company, so he took the initiative and called the delivery center, who then told him his vehicle had been involved in an accident during transit.

In keeping with their

Fyfe put down a $2500 deposit in June to order a $70,000 black performance Model 3. He was given a delivery day in early September, but when he tried to go get his car he was told by the company that it was still in California. Two more weeks went by without an update from the company, so he took the initiative and called the delivery center, who then told him his vehicle had been involved in an accident during transit.

After walking to work for two weeks, he then checked in on the status of his new vehicle. Tesla told him that they had one for him but it was still at the Fremont, California factory. In the interim, Tesla rented him a Cadillac to drive and he finally got his Model 3 on October 26.

Another buyer, Jonathan Berent, paid $1000 in 2016 to reserve the right to order a Model 3, then paid an additional $2500 this year as a deposit. In early September, he was told by the company that his car was near a delivery center by the Fremont plant and, after heading there with a check for the balance, he was given a VIN number and shown his car.

While the car was being detailed to be given to him he was told there was a mixup. The car that he was shown was apparently assigned to another customer who shared not the same last name but the same first name. They eventually found another car an hour away and when it arrived, it had paint defects that needed to be repaired. When he decided to cancel his order, he was contacted repeatedly over the coming weeks by sales representatives who told him they had a car ready for him. The company even went so far as to say they would deliver it to his home or to a nearby coffee shop if he wanted.

It's Elon Musk's genius and Tesla's outside the box thinking that have made these embarrassing complications possible, according to Mike Ramsey, a Gartner analyst.

He stated: "Tesla had a huge volume push in the third quarter, and they probably could have avoided a lot of this if they had traditional dealers."

Of course, if Tesla had a traditional dealership network, its cash burn would be orders of magnitude higher and probably would be out of business long ago, and while we doubt that this is what Elon meant when he said he wanted Tesla to be a "disruptor", we are quite confident that as Tesla ramps up production, this is only a glimpse of the first circle of delivery logistics hell" that Elon has warned about.

Flashback: July 17, 2017

Tesla Welcomes Linda Johnson Rice and James Murdoch as New Independent Directors to its Board

We would like to welcome Linda Johnson Rice, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Johnson Publishing Company (JPC), and James Murdoch, Chief Executive Officer of 21st Century Fox (21CF), to Tesla’s board of directors.

In addition to her role as Chairman and CEO of JPC and Fashion Fair Cosmetics, Linda is CEO of Ebony Media Operations and Chairman Emeritus of EBONY Media Holdings, the parent company for the EBONY and Jet brands. Linda has extensive corporate board experience, having previously served on the boards of a number of companies across a variety of industries, including:

Bausch & Lomb,

Continental Bank,

Quaker Oats,

Dial Corporation,

MoneyGram and Kimberly-Clark Corporation, and currently serving on the boards of Omnicom Group and Grubhub.

Linda is a Trustee at the Art Institute of Chicago, President of the Chicago Public Library Board of Directors, Council Member of The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, and board member of After School Matters and Northwestern Memorial Corporation.

Before becoming CEO of 21CF in 2015, James (Murdoch), held a number of leadership roles at the company over a two-decade career.

He previously served as its

Co-Chief Operating Officer,

Chairman and CEO for Europe and Asia, as well as

Chairman of BSkyB, Sky Deutschland, and Sky Italia, the businesses that now comprise Sky plc.

He also served as CEO of BSkyB and STAR, India’s entertainment leader.

In addition to being a key driver of 21CF’s domestic and international expansion, James has been instrumental in the company’s robust social impact initiatives, including its decade-long leadership on environmental sustainability.

James and his wife, Kathryn Murdoch, are founders of a family foundation, Quadrivium, which supports initiatives involving natural resources, science, civic life, childhood health, and equal opportunity.

We are excited to welcome Linda and James to the Tesla board

Built And Tested in Southern California, Tesla's Model 3 Meets Its Enemy: The Winter

Even though Tesla technically began delivery of its Model 3 vehicles last year, the first few months of deliveries took place in California where there was no notable cold weather. It took some time for the Model 3 to make its way east and to colder climates, but it finally has, spurring a litany of complaints.

The recent cold front coming through Quebec, where temperatures went slightly below freezing for the first time this year, resulted in a number of reports from local Model 3 owners facing issues with things like door handles, windows and charge ports, reports Zero Hedge.

But don’t take it from these reports, take it from the editor of the pro-Tesla blog electrek himself, Frederick Lambert. He decided to do some testing of his own after reading this report and, on a whim, arrived at the exact same problems. He documented his problems on a YouTube video.

As you can see by viewing the video, he struggles for about a minute, with his bare hands in the freezing cold, just to get the door handle to pop out so he can open his driver side door. Welcome to the future of automobiles.

He claims that preheating was on for about 10 minutes before he even walked up to his car. Prior to turning on preheating, the temperature outside the vehicle was -7C (19F) and the temperature inside the vehicle was about 1C (34F). The preset temperature for his car was 22C (about 71F). Those temperatures shouldn't be too troublesome, he alludes, because they weren't even cold enough to activate the battery pre-heating feature in the car.

Lambert says he has gotten "a dozen" reports of Model 3 owners having the same types of issues. Some have also complained about the charge port door not opening and closing as it should, despite Lambert being able to do so in his video.

What's his advice to other Tesla owners?

"In the meantime, the best solution is likely to overheat the cabin for a longer period of time before trying to unlock the Model 3. Of course, it’s not really convenient or efficient, but it’s the best I can think of for now.

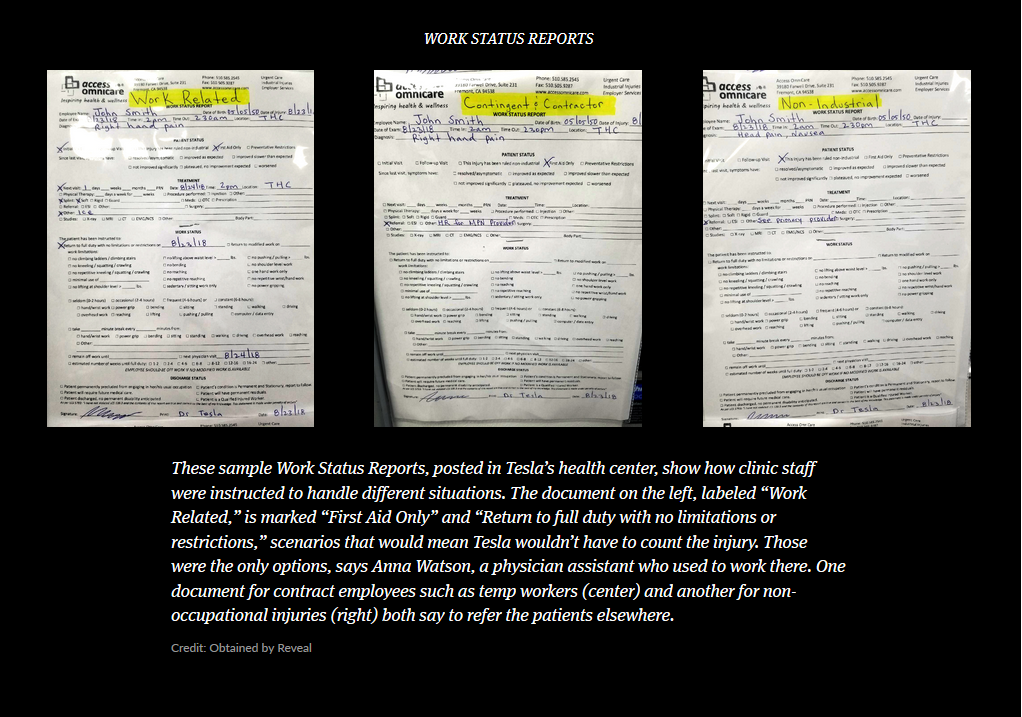

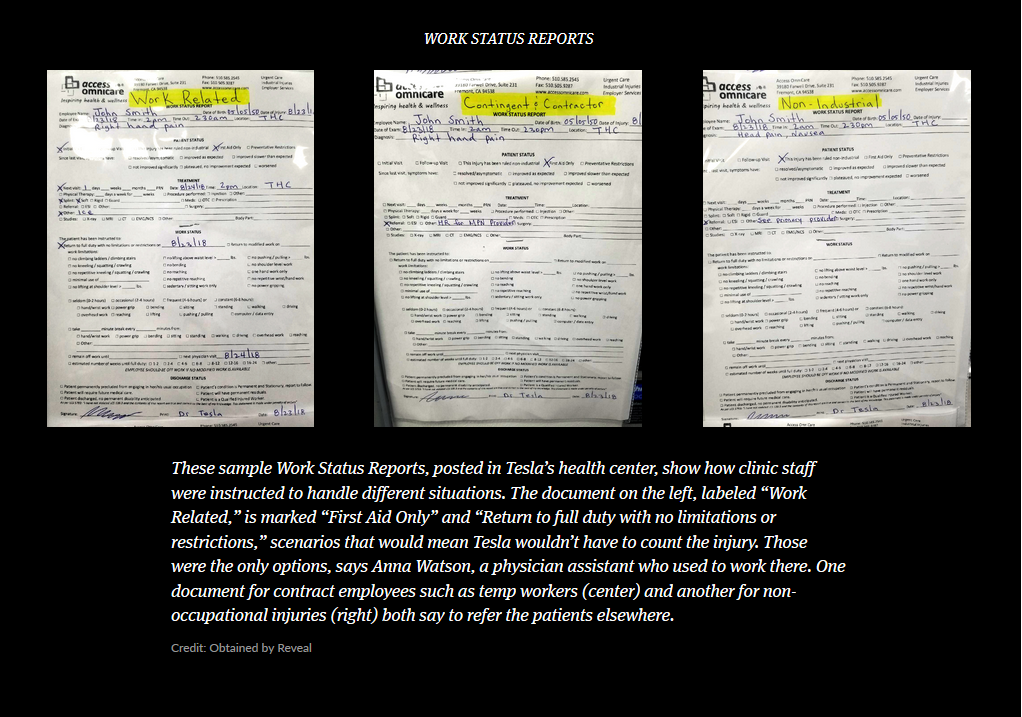

Inside Tesla’s factory, a medical clinic designed to ignore injured workers

By Will Evans / November 5, 2018

Snip:

When a worker gets smashed by a car part on Tesla’s factory floor, medical staff are forbidden from calling 911 without permission.

The electric carmaker’s contract doctors rarely grant it, instead often insisting that seriously injured workers – including one who severed the top of a finger – be sent to the emergency room in a Lyft.

Injured employees have been systematically sent back to the production line to work through their pain with no modifications, according to former clinic employees, Tesla factory workers and medical records. Some could barely walk.

The on-site medical clinic serving some 10,000 employees at Tesla Inc.’s California assembly plant has failed to properly care for seriously hurt workers, an investigation by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting has found.

The clinic’s practices are unsafe and unethical, five former clinic employees said.

But denying medical care and work restrictions to injured workers is good for one thing: making real injuries disappear.

“The goal of the clinic was to keep as many patients off of the books as possible,” said Anna Watson, a physician assistant who worked at Tesla’s medical clinic for three weeks in August.

Watson has nearly 20 years of experience as a medical professional, examining patients, diagnosing ailments and prescribing medications. She’s treated patients at a petroleum refinery, a steel plant, emergency rooms and a trauma center. But she said she’s never seen anything like what’s happening at Tesla.

Anna Watson was a physician assistant at the medical clinic inside Tesla’s electric car factory in Fremont, Calif. She was fired in August after raising concerns.Credit: Paul Kuroda for Reveal

“The way they were implementing it was very out of control,” said Watson, who was fired in August after she raised her concerns. “Every company that I’ve worked at is motivated to keep things not recordable. But I’ve never seen anybody do it at the expense of treating the patient.”

Workers with chest pain, breathing problems or extreme headaches have been dismissed as having issues unrelated to their work, without being fully evaluated or having workplace exposures considered, former employees said. The clinic has turned away temp workers who got hurt on Tesla’s assembly lines, leaving them without on-site care. And medical assistants, who are supposed to have on-site supervision, say they were left on their own at night, unprepared to deal with a stream of night-shift injuries.

If a work injury requires certain medical equipment – such as stitches or hard braces – then it has to be counted in legally mandated logs. But some employees who needed stitches for a cut instead were given butterfly bandages, said Watson and another former clinic employee. At one point, hard braces were removed from the clinic so they wouldn’t be used, according to Watson and a former medical assistant.

As Tesla races to revolutionize the automobile industry and build a more sustainable future, it has left its factory workers in the past, still painfully vulnerable to the dangers of manufacturing.

An investigation by Reveal in April showed that Tesla prioritized style and speed over safety, undercounted injuries and ignored the concerns of its own safety professionals. CEO Elon Musk’s distaste for the color yellow and beeping forklifts eroded factory safety, former safety team members said.

The new revelations about the on-site clinic show that even as the company forcefully pushed back against Reveal’s reporting, behind the scenes, it doubled down on its efforts to hide serious injuries from the government and public.

In June, Tesla hired a new company, Access Omnicare, to run its factory health center after the company promised Tesla it could help reduce the number of recordable injuries and emergency room visits, according to records.

A former high-level Access Omnicare employee said Tesla pressured the clinic’s owner, who then made his staff dismiss injuries as minor or not related to work.

“It was bullying and pressuring to do things people didn’t believe were correct,” said the former employee, whom Reveal granted anonymity because of the worker’s fear of being blackballed in the industry.

Dr. Basil Besh, the Fremont, California, hand surgeon who owns Access Omnicare, said the clinic drives down Tesla’s injury count with more accurate diagnoses, not because of pressure from Tesla. Injured workers, he said, don’t always understand what’s best for them.

“We treat the Tesla employees just the same way we treat our professional athletes,” he said. “If Steph Curry twists his knee on a Thursday night game, that guy’s in the MRI scanner on Friday morning.”

Yet at one point, Watson said a Tesla lawyer and a company safety official told her and other clinic staff to stop prescribing exercises to injured workers so they wouldn’t have to count the injuries. Recommending stretches to treat an injured back or range-of-motion exercises for an injured shoulder was no longer allowed, she said.

The next day, she wrote her friend a text message in outrage: “I had to meet with lawyers yesterday to literally learn how not to take care of people.”

Tesla declined interview requests for this story and said it had no comment in response to detailed questions. But after Reveal pressed the company for answers, Tesla officials took time on their October earnings call to enthusiastically praise the clinic.

“I’m really super happy with the care they’re giving, and I think the employees are as well,” said Laurie Shelby, Tesla’s vice president for environment, health and safety.

Musk complained about “unfair accusations” that Tesla undercounts its injuries and promised “first-class health care available right on the spot when people need it.”

Welcome to the new Tesla clinic

Injured workers sent back to work

Other ways Tesla’s clinic avoids treating workers

State regulators not interested

Clinic source: Tesla pressured doctor

By Will Evans / November 5, 2018

Snip:

When a worker gets smashed by a car part on Tesla’s factory floor, medical staff are forbidden from calling 911 without permission.

The electric carmaker’s contract doctors rarely grant it, instead often insisting that seriously injured workers – including one who severed the top of a finger – be sent to the emergency room in a Lyft.

Injured employees have been systematically sent back to the production line to work through their pain with no modifications, according to former clinic employees, Tesla factory workers and medical records. Some could barely walk.

The on-site medical clinic serving some 10,000 employees at Tesla Inc.’s California assembly plant has failed to properly care for seriously hurt workers, an investigation by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting has found.

The clinic’s practices are unsafe and unethical, five former clinic employees said.

But denying medical care and work restrictions to injured workers is good for one thing: making real injuries disappear.

“The goal of the clinic was to keep as many patients off of the books as possible,” said Anna Watson, a physician assistant who worked at Tesla’s medical clinic for three weeks in August.

Watson has nearly 20 years of experience as a medical professional, examining patients, diagnosing ailments and prescribing medications. She’s treated patients at a petroleum refinery, a steel plant, emergency rooms and a trauma center. But she said she’s never seen anything like what’s happening at Tesla.

Anna Watson was a physician assistant at the medical clinic inside Tesla’s electric car factory in Fremont, Calif. She was fired in August after raising concerns.Credit: Paul Kuroda for Reveal

“The way they were implementing it was very out of control,” said Watson, who was fired in August after she raised her concerns. “Every company that I’ve worked at is motivated to keep things not recordable. But I’ve never seen anybody do it at the expense of treating the patient.”

Workers with chest pain, breathing problems or extreme headaches have been dismissed as having issues unrelated to their work, without being fully evaluated or having workplace exposures considered, former employees said. The clinic has turned away temp workers who got hurt on Tesla’s assembly lines, leaving them without on-site care. And medical assistants, who are supposed to have on-site supervision, say they were left on their own at night, unprepared to deal with a stream of night-shift injuries.

If a work injury requires certain medical equipment – such as stitches or hard braces – then it has to be counted in legally mandated logs. But some employees who needed stitches for a cut instead were given butterfly bandages, said Watson and another former clinic employee. At one point, hard braces were removed from the clinic so they wouldn’t be used, according to Watson and a former medical assistant.

As Tesla races to revolutionize the automobile industry and build a more sustainable future, it has left its factory workers in the past, still painfully vulnerable to the dangers of manufacturing.

An investigation by Reveal in April showed that Tesla prioritized style and speed over safety, undercounted injuries and ignored the concerns of its own safety professionals. CEO Elon Musk’s distaste for the color yellow and beeping forklifts eroded factory safety, former safety team members said.

The new revelations about the on-site clinic show that even as the company forcefully pushed back against Reveal’s reporting, behind the scenes, it doubled down on its efforts to hide serious injuries from the government and public.

In June, Tesla hired a new company, Access Omnicare, to run its factory health center after the company promised Tesla it could help reduce the number of recordable injuries and emergency room visits, according to records.

A former high-level Access Omnicare employee said Tesla pressured the clinic’s owner, who then made his staff dismiss injuries as minor or not related to work.

“It was bullying and pressuring to do things people didn’t believe were correct,” said the former employee, whom Reveal granted anonymity because of the worker’s fear of being blackballed in the industry.

Dr. Basil Besh, the Fremont, California, hand surgeon who owns Access Omnicare, said the clinic drives down Tesla’s injury count with more accurate diagnoses, not because of pressure from Tesla. Injured workers, he said, don’t always understand what’s best for them.

“We treat the Tesla employees just the same way we treat our professional athletes,” he said. “If Steph Curry twists his knee on a Thursday night game, that guy’s in the MRI scanner on Friday morning.”

Yet at one point, Watson said a Tesla lawyer and a company safety official told her and other clinic staff to stop prescribing exercises to injured workers so they wouldn’t have to count the injuries. Recommending stretches to treat an injured back or range-of-motion exercises for an injured shoulder was no longer allowed, she said.

The next day, she wrote her friend a text message in outrage: “I had to meet with lawyers yesterday to literally learn how not to take care of people.”

Tesla declined interview requests for this story and said it had no comment in response to detailed questions. But after Reveal pressed the company for answers, Tesla officials took time on their October earnings call to enthusiastically praise the clinic.