A Study Designed to Confuse

When we dig into the methods, the implausibility becomes obvious.

The study

only counted people with a prescription for melatonin—which is common in the U.K. but almost nonexistent in the U.S., where melatonin is sold over the counter. As the authors admit:

“Everyone taking it as an over-the-counter supplement… would have been in the non-melatonin group.”

This means that millions of people who actually use melatonin nightly were classified as non-users, while the so-called “melatonin group” was composed almost entirely of patients sick enough to have their sleep problems documented and treated in medical systems requiring prescriptions.

That’s not a safety signal — it’s a

statistical illusion.

Confounding, Not Causation

Even if the data were reliable, the confounders are overwhelming. Chronic insomnia often travels with anxiety, depression, hypertension, and metabolic dysfunction — each a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Matching patients by demographics or comorbidities doesn’t erase the underlying

severity bias: those who seek prescriptions tend to be those who are already unwell.

Moreover, the researchers lacked basic data on:

- Sleep quality and circadian rhythm disruption

- Lifestyle factors (diet, alcohol, shift work, screen exposure)

- Supplement dosage and purity

- Psychiatric medications used concurrently

Without these, there’s no meaningful inference about melatonin itself.

Moreover, the study failed to account for several

key pharmacological confounders. While the authors excluded patients taking benzodiazepines, they did

not control for other pharmaceutical sleep drugs such as zolpidem (

Ambien), eszopiclone (

Lunesta), or trazodone — all of which carry well-documented cardiometabolic risks. Nor did they adjust for the use of

statins,

SSRIs, or

antihypertensives, which are both common among insomnia patients and known to alter cardiovascular function (learn more about the

cardiotoxicity of statin drugs) and sleep architecture. Failing to isolate these variables makes it

virtually impossible to determine whether the observed risks stem from melatonin itself or from concurrent drug exposure.

The Biological Reality: Melatonin as a Protector

For decades, melatonin has been one of the most studied molecules in the realm of oxidative stress and cardiometabolic protection. Peer-reviewed studies have shown that it:

- Reduces blood pressure and improves endothelial function

- Protects mitochondria and heart tissue after ischemic injury

- Mitigates oxidative damage and inflammation across numerous organs

A 2022 meta-analysis in the

Journal of Pineal Research found melatonin to be broadly cardioprotective, not cardiotoxic.

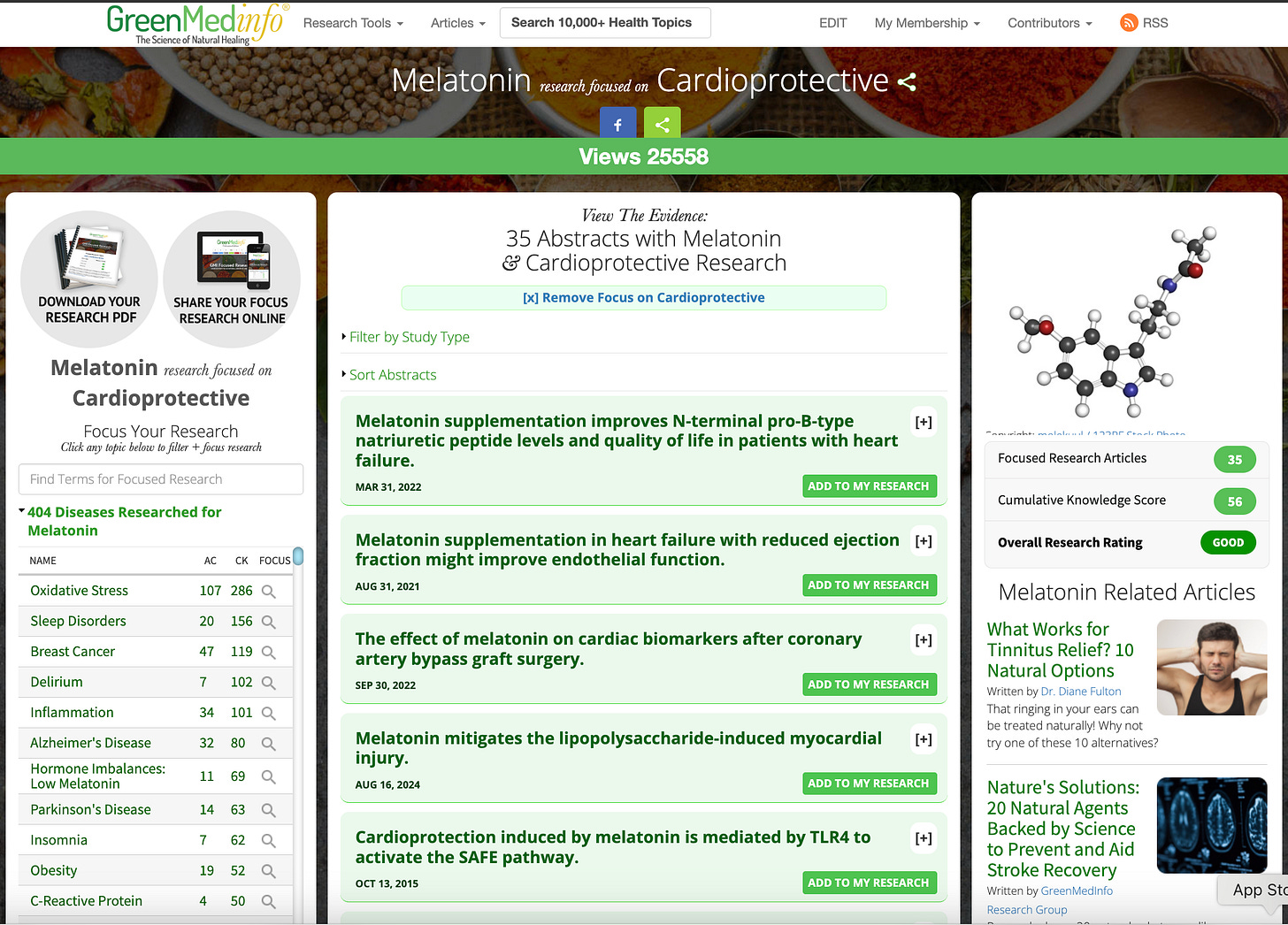

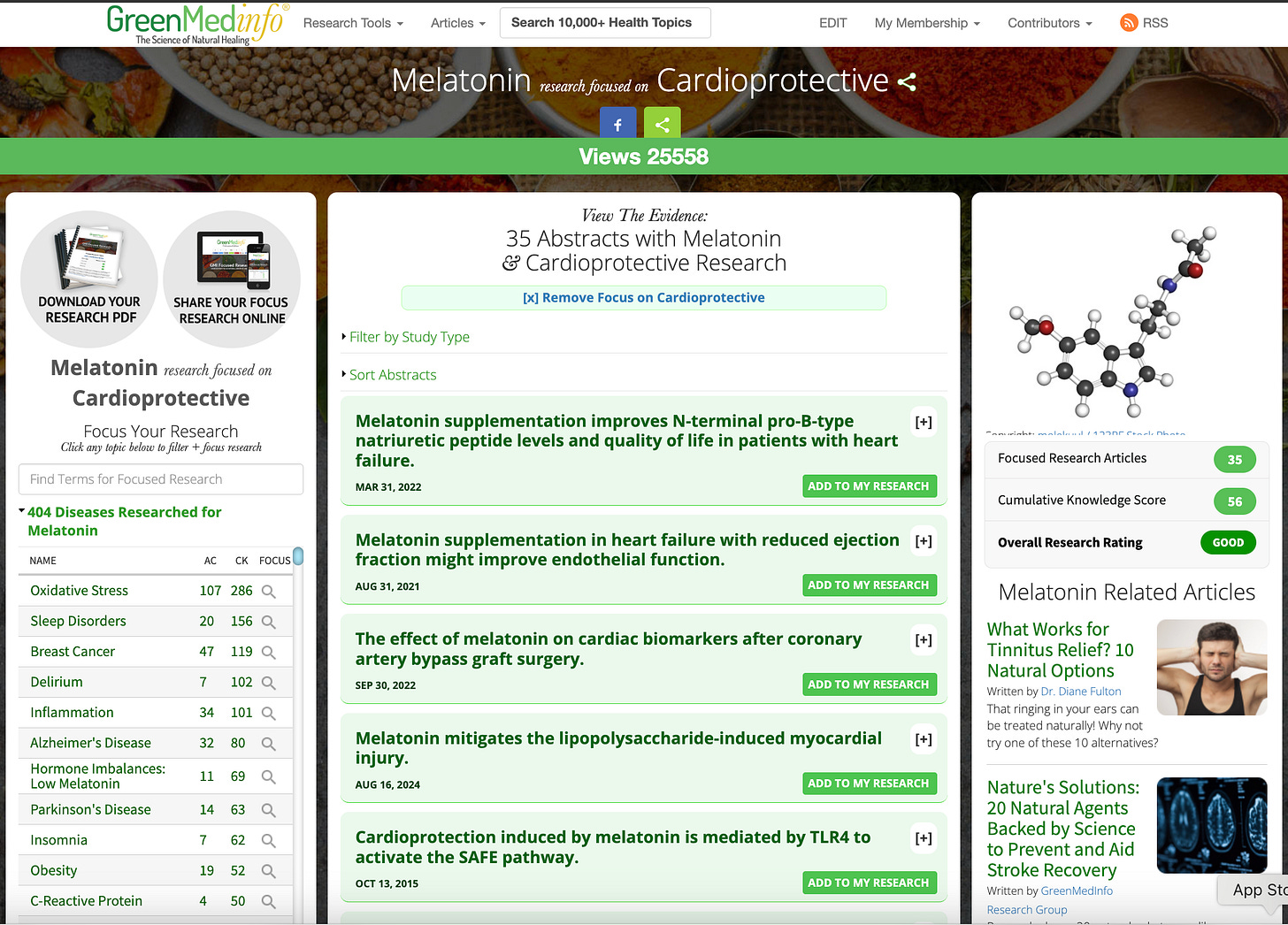

This aligns with the

GreenMedInfo research database, which has indexed nearly

1,000 studies on melatonin’s diverse physiological benefits across more than

400 health conditions, and documents up to

130 distinct pharmacological actions of the molecule — including

antioxidant,

anti-inflammatory,

neuroprotective, and

cardioprotective effects (

see the research compendium here).

Within this body of literature, there are

dozens of studies specifically identifying melatonin’s cardioprotective roles — from improving myocardial recovery to reducing ischemia-reperfusion injury and modulating autonomic balance (

cardiovascular studies here).

To reverse that entire corpus of evidence based on a five-minute abstract summary would be scientifically reckless.