Terrorist charges like the ones used to convict the two women have become commonplace in Turkey, especially since a failed attempt by parts of the military to overthrow President Tayyip Erdogan in 2016. Mass arrests followed.

Also increasingly common is the practice of switching judges during a trial, more than a dozen lawyers and other legal sources told Reuters. Turkish officials say such changes are merely routine, for health or administrative reasons. Lawyers interviewed by Reuters say they are convinced it’s a way for the government to exert control over the courts.

“The constant reshuffling of judges is a simple but very useful mechanism. For every time the government gets involved like this in the judiciary, there are hundreds more cases where the judges learn their lesson” not to act against perceived government interests, said Gareth Jenkins, a political analyst based in Istanbul.

Neither Erdogan’s office nor the justice ministry responded to detailed questions for this article by the time of publication. Mehmet Yilmaz, deputy chairman of the Council of Judges and Prosecutors, the state-body that appoints law officials, said Turkey’s legal system is “not behind any country in the world.”

The judiciary has been used as an instrument to advance political agendas in Turkey for decades. Under Erdogan, his opponents say, it has been deployed as a political cudgel and hollowed out to an unprecedented degree.

Under his purge, thousands of judges and prosecutors have been sacked, by the government’s own count. They have been replaced by inexperienced newcomers, ill-equipped to handle the dramatic spike in workload from coup-related prosecutions. At least 45% of Turkey’s roughly 21,000 judges and prosecutors now have three years of experience or less, Reuters calculated from Ministry of Justice data.

“We aren’t claiming that the judiciary was independent from governments before,” said Zeynel Emre, a lawmaker from the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP). “However, a period like this where the government wields the judiciary like a sword on politics and especially the opposition is unprecedented.”

At the time of their arrest in late 2016, Kisanak and Tuncel were prominent figures in the Kurdish minority’s decades-long campaign for social, economic and political equality. Kisanak, 58, a former journalist, had recently been elected Diyarbakir’s mayor. Tuncel, 44, was a lawmaker in parliament, representing an Istanbul constituency. They were jailed for 14 and 15 years, respectively, for spreading terrorist propaganda and belonging to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which is banned in Turkey and branded a terrorist organization by the U.S. and EU. They denied the charges.

Istanbul Bar Association chairman Mehmet Durakoglu said that by using the judiciary as a tool against its opponents, Erdogan’s government “has achieved what it couldn’t do by political means” at the ballot box. The Turkish government counters that its legal system is as advanced as any Western country and that threats against its national security require strict anti-terrorism laws.

Yilmaz, from the state Council of Judges and Prosecutors, acknowledged “we have been experiencing problems like an increase in work. Our workload is considerably above the global average.”

CHALLENGES

Erdogan has towered over Turkish politics for nearly two decades, first as prime minister, from 2003 to 2014, and since then as president.

There have been challenges to his rule. In 2013, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets to protest policies they deemed authoritarian. The trigger was a government plan to build on a small park in downtown Istanbul. Two years later, peace talks broke down between the government and the militant PKK, which for decades had been waging a violent separatist campaign. In July 2016 came the coup attempt.

On each occasion, the authorities responded with a crackdown.

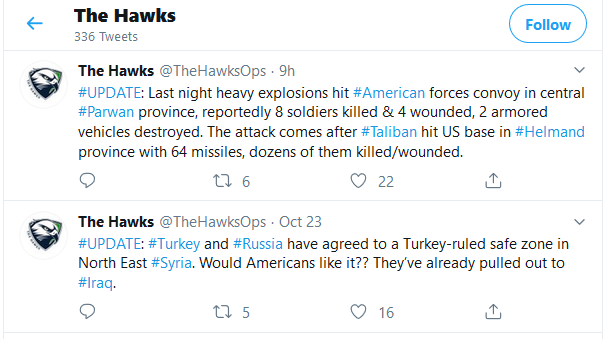

The pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), the second-biggest opposition party in Turkey’s parliament, says thousands of its members and supporters have been detained or jailed since the collapse of peace talks between Turkish authorities and the PKK. Among them is the party’s former co-leader, Selahattin Demirtas, who has been held since 2016 on terrorism charges that he denies.

Lawyers defending HDP supporters have also faced prosecution. In 2017, Aydin, the chairman of the Diyarbakir lawyers’ bar, was fined for disrupting court proceedings. The complaint stemmed from 2012, when Aydin and other defence lawyers walked out of a mass trial of Kurdish activists accused of belonging to the PKK. Aydin and his colleagues were protesting the court’s decision to dismiss their clients from the chamber. The case against Aydin was only brought up five years later.

The practice of keeping watch over lawyers and activists “is also part of the same trend, the same mentality, keeping track of everyone and making sure there is a file ready against everyone, just in case,” said Aydin. “If you start talking too much, if you criticise the government too much, if you take on high profile cases, or in my case, if you become a famous lawyer.”

Prosecutions have extended to academics. Around four dozen academics were convicted of spreading terrorist propaganda for signing a petition in 2016 that called for an end to the conflict with Kurdish militants and criticised the Turkish military’s campaign in the Kurdish southeast. They were sentenced to up to three years in jail.

Turkey’s Constitutional Court, which oversees laws, overturned the verdicts last year, ruling the prosecutions violated academics’ right to freedom of expression. A few days later, responding to criticism of its decision by some politicians and media, the court issued a statement saying the ruling “does not mean that the Constitutional Court shares the same opinions or supports these opinions.”

Yonca Demir, an academic at Istanbul Bilgi University was among the more than 2,000 signatories to the petition that sparked the mass arrest. She called her trial a sham.

“Whatever you say in court has no impact whatsoever on the judges. From the indictment to the rulings, everything was a copy-paste,” Demir said. “Yes, everyone has political views, but they should stick to the law. Instead, they show their ideologies in court.”

POST COUP

Erdogan blamed U.S.-based cleric Fethullah Gulen for orchestrating the failed 2016 coup and set about purging his supporters from public office. Gulen denies any involvement.

Nearly four years later, more than 91,000 people have been jailed and over 150,000 people have been sacked or suspended from their jobs over alleged links to Gulen. Charges include using the services of a bank founded by Gulen’s followers and communicating through an encrypted messaging app that Ankara says was used by Gulen’s network.

The purge has hollowed out Turkey’s justice system even as the caseload has exploded. By last November, 3,926 judges and prosecutors had been sacked from their posts, Justice Minister Abdulhamit Gul told parliament. More than 500 are in jail. The expulsions have resulted in a shortage of experienced judges and prosecutors, the president of Turkey’s Supreme Court of Appeals, Ismail Rustu Cirit, told Reuters.

The purges have added to the workload of Turkey’s judicial system. More than half a million people have been investigated since the coup attempt. As of late 2019, around 30,000 were still awaiting trial as the courts try to process the vast number of coup-related cases. Some suspects have been jailed for months without an indictment or a trial date.

Speaking last year at a ceremony to honour the police, Erdogan said that authorities had still not fully rooted out Gulen’s followers and Turkey could not and would not let up in its crackdown. Erdogan’s lawyer, Huseyin Aydin, told Reuters the coup trials were “the fairest proceedings in modern Turkish history.”

The laws were applied to the letter, said Aydin, who isn’t related to the human-rights attorney. “When we look at the general Turkish judicial traditions, these are cases that have most accurately obeyed the principles of law,” Aydin said. “Our judiciary is passing the test with flying colours.”

Not all Turkey’s lawyers agree. In August, 51 of the country’s 81 bar associations, including those of its three largest cities of Ankara, Istanbul and Izmir, boycotted a judges’ ceremony at Erdogan’s presidential palace. The choice of venue, they said, signalled a lack of separation of powers and violated their code of ethics. The Ankara bar association said Turkey’s judicial system had descended into chaos with lawyers jailed, the defence muzzled and confidence in judges and prosecutors destroyed.

New waves of arrests continue, most recently over online criticism of the government’s response to the global coronavirus outbreak. The Interior Ministry said last week that 402 people had been detained for “baseless and provocative posts” about the pandemic.

The Young Ones

Acknowledging his ministry’s struggles with personnel, Justice Minister Gul told parliament last year that Turkey was aiming to increase the number of judges and prosecutors.

Figures from Turkey’s Board of Judges and Prosecutors show at least 9,323 new judges and prosecutors have been recruited since the coup attempt. That means that at least 45% of Turkey’s roughly 21,000 judges and prosecutors have three years of experience or less.

Hakki Koylu, chairman of the Justice Commission in Turkey’s parliament and a lawmaker for Erdogan’s AK Party, acknowledged to Reuters that some judges and prosecutors “have been appointed without adequate training.”

“Unfortunately, it all happens quite haphazardly,” Koylu said. “We see some of the rulings they make. Now we can only hope that the upper courts correct these rulings” upon appeal. But the Supreme Court of Appeals, the highest appeals court, has been hollowed out too.

Cirit, the court’s president, told Reuters the appointment of judges with less than five years experience to the Supreme Court of Appeals “poses risks not only for the reasonable duration of proceedings, but also for the right to a fair trial.” New judges often lack experience, a dozen lawyers and current and former judges said.

“I became a judge in a criminal court at the age of 48,” said Koksal Sengun, who retired in 2013. Now, after the widespread dismissals and new appointments, Sengun said, the average age of judges in some provinces has fallen to 25. He didn’t say what data his observation about the average age was based on.

“In my opinion, the minimum age for criminal court should be 40. Maybe even higher,” Sengun said. “You have to climb the stairs one by one. In the current system, they are appointed so early.” That lack of training leaves newcomers with too little of the emotional and mental toughness needed in the job, he argued. “These judges have three or five years experience, sitting at the top of a court that hands down the heaviest sentences. These kids come under such pressure, and get crushed. You can’t expect much from such a young judge.”

The impact of such inexperience goes beyond criminal cases. Yesim, a commercial lawyer practicing in Istanbul, described chaotic proceedings in one case. She spoke on condition that her full name not be used.

The case, she said, was “very simple,” a dispute over a small debt involving two companies. The judge had no trouble making the ruling. Then, to Yesim’s surprise, he sought a favor. “The judge, who seemed younger than 25, asked me, ‘Ms. Lawyer, can you help me with writing the verdict? I am not sure about the style.’ I couldn’t help but laugh, but we wrote the ruling together,” she said.

Turkey shows no sign of changing course. After the attempted coup, the country cancelled a European Union training program for Turkish judicial officials and opted to train its judges and prosecutors itself. The European Commission wrote in its annual 2019 report that large scale recruitments of new judges and prosecutors are “concerning.” Turkey countered that the EU’s criticisms were unfair and disproportionate.

Lawyer Veysel Ok has defended several journalists against accusations they are part of Gulen’s network. He was awarded last year’s international Thomas Dehler Medal, named for the German lawyer who defended Jewish citizens against Nazi persecution, in recognition of his work in defence of freedom of speech and the rule of law. Ok said young judges are being promoted because of their political connections, with little life experience, let alone professional experience.

“This is, by itself, an injustice,” Ok said. “In the past, we used to research the judges when they were appointed to a case we were representing, and we would adjust our defence according to past rulings they’d handed down and their political views.” Times have changed, he joked darkly. “Now we don’t have to, because we know they are all pro-government.”