Awhile back I found an interesting article on sott here, and it spurred me to check out the book discussed. It's called Tell your Children: the truth about marijuana, mental illness, and violence. Its author (Alex Berenson) is a former New York Times writer who also happens to be a Covid-19 skeptic as well, so I get the impression that he is unusually candid and truthful for a journalist formerly affiliated with the NYT.

After devouring the book I wanted to share some of the information in it on here, because it provides some very hard facts and information about an issue which has bad societal consequences and which has received almost no pushback from the public, at least in North America where I live.

From his website:

The book broadly covers three topics The first covers the modern history of cannabis, starting with Mexico and India in the 19th century and leading up to the recent round of legalization of the 2010's in the United States. The second studies the found connections between marijuana, psychosis, and schizophrenia, also touching on the opioid epidemic. The final part talks about the links between psychosis/schizophrenia and brutal, senseless violence, and how these and other types of crime are increasing disproportionately in places where marijuana is legal. The author brings a lot of studies on each occasion, and they are sobering. The anecdotes about some of the brutal assaults and murders can be rough to read also, so fair warning.

Despite being new to European society and the New World (mostly introduced via the importation of hemp for fiber) marijuana was known throughout most of Asia historically. The oldest recorded reference the the effects of cannabis are in the Chinese pharmacopia called the Pen-ts'ao Ching, written as early as 100 AD, which warned that excessive cannabis consumption caused one to "see spirits."

India

In India, hemp was farmed and traded in heavily by the British, which paid little attention to cannabis in general in the early days of Indian colonisation until the establishment of mental institutions in India in the 1800s and the record-keepers there began to see patterns and connections between ganja and institutionalization of its users by friends or family members. In 1873 the government published survey results finding an increase in insanity and insanity-linked violence due to its habitual use, and recommended higher taxes to discourage consumption.

A later report in 1893, spurred by a British politician concerned about the effects of marijuana, instead concluded that the link was not strong, and therefore was fine to be kept as a taxed and regulated industry. While this report was hailed as a breakthrough in marijuana scholarship by activists, there were several flaws in it. In India, cannabis had three traditional modes of consumption. The first is called bhang, which is a cannabis paste blended into milkshakes and consumed during festivals. The psychoactive potency of these is quite low. Then there is ganja and chara, which in the west are known as the bud and hashish forms of marijuana respectively. These had much higher potency and its users tended to be much heavier, daily users; they were also universally looked down upon by traditional Indian society in ways very similar to how western society stereotypes potheads. And it was these individuals who tended to make up the bulk of those admitted to institutions for drug-induced insanity or violence. Of the British commissioners who approved the report to inform state policy, there were three Indians; two of those three opposed the findings. One of them named Nihal Chand (Punjab Lawyer) published a scathing critique of the study's failures to distinguish between the different types of cannabis consumed. In retrospect what was seen as a victory for social liberalism could instead be seen as the British profiting off of the societal ills that some modes of marijuana consumption produced.

Even after the commission report, other doctors working with mental patients would continue to come forth about how a certified lunatic's friends, relatives, and even the patient him or herself would admit to and blame cannabis. People would improve after being off the drug, leave, relapse, and be re-admitted with regularity, and with symptoms which today would be readily classifiable as psychosis. Twenty percent of those classified as criminal lunatics had their violence linked to cannabis use also. What was striking was that the violence was often unprovoked, against family members and strangers alike. One does not need to be a psychiatrist to know that those in psychosis are dangerous individuals. Everyone knows to avoid the dishevelled man whose every other word is a swear word and whose every other sentence is about God.

Mexico

Contrasting India (a Hindu British colony of 330 million people with a long history of cannabis use) is Mexico; in the 19th century it was Catholic, recently independent, and had 13 million people and a native population that was new to cannabis but familiar with other psychoactive plants such as peyote and salvia. It was not a major industry, and was used mostly by soldiers and the poor.

In spite of all these cultural differences, doctors in Mexico in the 1800s also noticed a link between marijuana use, insanity, and violence. This was a finding reported by a University of Cincinnati professor Isaac Campos in 2012 in a history called Home Grown: Marijuana and the Origins of Mexico's War on Drugs. This was a critical work because it exploded the myth that some activists and scholars have perpetuated in the United States, blaming the US prohibition for Mexico's war on drugs. The truth is that Mexico banned the sale of marijuana long before it became a subject of interest to narcotics control policy-wonks in the US and Europe.

Leading up to this were increasing bouts of violence, and increased defense pleas linked to marijuana-induced insanity. One of the highest profile cases was an incident in which the governor of Mexico city claimed that he murdered a political rival "under the influence," as we say today.

The most potent type was called sinsemilla (i.e. "without seed"), and was estimated to be around 10% THC.

United States (1900 to 1979)

As the fears about marijuana in the United States increased throughout the 1910s and 1920s, with more local and state-wide laws restricting its sale coming into effect, the first federal law restricting the drug was passed in 1937 and imposed a $100/oz tax on marijuana for purposes other than very limited industrial or medicinal use. One character which gets bandied about a lot in this time period was Harry J. Anslinger, who was the commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. He created reports on some highly publicized incidents of violence caused by perpetrators supposedly in the throes of a marijuana psychosis. The evidence of marijuana's connection to violence was a lot weaker then than it was today, ironically. One of the casualties of this time was the hemp industry. At the time THC was not yet discovered, and so it was not possible to gauge the psychoactive properties of a hemp plant scientifically. Anslinger like many of the time was also openly racist, which is fact heavily exploited by advocates to retroactively malign opposition to marijuana as of racist origin.

Around the time of its prohibition, the percentage of Americans who tried marijuana was still in the single digits. Once the counter-cultural movement (psyop) picked up, that increased to 12 percent by 1973; for those 18 to 24 it was 50 percent. It was around this time that advocacy for legalization became more common. The flagship for this was the magazine High Times, published by Tom Forcade. His rational that High Times could be a beachhead for more liberal attitudes toward a vice traditionally looked down upon, similar to how Playboy was for pornography. Alongside this cultural operation was the advocacy group National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), founded by a young Indiana lawyer in 1970 named Keith Stroup, who was even financially backed by Hugh Hefner.

A lot of the strategy around this time in history revolved around reducing the sentences for marijuana consumption. Some of the most draconian laws existed in Texas, where one could get 9 years in jail for smoking marijuana. By 1973 possession was a felon in only two states, although a misdemeanor offense could still give someone a year in jail. And the amount of arrests increased twenty-fold between 1965 and 1973 with increased use of the drug. So at this point it began to have a larger impact on middle class white families, and the full impact of these types of laws were brought to bear more in the public consciousness, making them receptive to the message of reform. Oregon ended up being the first state to decriminalize in 1973, with four more states following two years later.

In addition to the harsh legal penalties, another factor contributing to the loosening of marijuana laws was the fact that it did not seem as dangerous as the forbears of the marijuana issue in the US made it out to be. People were not committing the heinous and senseless crimes of marijuana-induced psychosis dubbed "reefer madness."

The reason for this was quite simple. The weed imported en masse from Mexico was often of extremely cheap quality, even intermixed with seeds and other weeds. With the discovery of THC in 1967, testing found that US marijuana was rarely over two percent THC, with some measures even dipping below one percent. For reference today, any cannabis plant with less than 0.3 percent HTC is considered a hemp plant. To compare this to the Indian classifications, the majority of Americans smoking pot around this time were consuming the equivalent of bhang, which causes a mild buzz after consuming a lot. A group would need to share fifty joints in order for each smoker to receive 25 - 50 mg THC. This fact led to the common enough trope that people "didn't feel anything" after smoking a joint with friends. Mexican sinsemilla at the time was prohibitively expensive in the US ($400/oz pre-inflation).

Contrasting this is today's marijuana, which is normally 20 - 25 percent THC. A single joint delivers more than 100 mg of the drug: far more potent than anything the Mexicans had access too back in the 19th century. This moves modern marijuana use more toward the category of ganja or chara, which was often implicated as a cause of psychosis or worsening schizophrenia or bipolar disorder for those institutionalized.

Amusingly enough, on the heels of this decriminalization was the growth of the drug paraphenalia trade, which even had its own trade association. This group became increasingly notorious as the perception became more common they were marketing drug paraphernalia to minors. This led to a backlash by parents, which were becoming increasingly aware of the effects of the drug on their children, especially habitual users.

On top of this was a scandal in 1977 involving Dr Peter Bourne (President Jimmy Carter's drug policy advisor) who had in fact was discovered to have used both marijuana and cocaine with Keith Stroup (of NORML); this telegraphed the notion loudly that the biggest advocates for legalization were just interested in getting high. This scandal, fueled by the "gateway drug" hypothesis from the 1950's was a lightning bolt to the American consciousness and instantly associated marijuana with cocaine, the use of which in 1979 had tripled since 1972. Stroup eventually resigned from NORML a year later and the movement to decriminalize marijuana went into hibernation until the 1990s.

United States (1980 - present)

In spite of acute awareness of the harm of cocaine, its use continued to spread due to decreasing prices. Following this was the rise of crack (cocaine baked with baking soda and water into a smokeable pellet). This trend led to a rising tide of crime and violence in the US, rising 41 percent from 1983 to 1991. The number of dead was almost half of the amount of American men killed in Vietnam over the course of the war. Alongside this was the explosion in AIDS among gay men and heroin users. During this time marijuana use continued to decline.

Dr Ethan Nadelmann, a 1979 Harvard graduate in the law-PhD program, viewed the source of all these problems with violence as prohibition, drawing analogies between the current drugs in vogue and alcohol. Throughout the 1980's he fought an uphill battle to get greater recognition for the problems prohibition created, while toning down rhetoric about the legalization of the drugs themselves. After a fortuity lunch with the billionaire investor George Soros he received financial backing to advocate for the liberalization of the drug laws in the United States and elsewhere. With this backing he founded the Lindesmith Center (named after a sociologist who was also an advocate for decriminalization) to advocate for drug policy reform.

One of the first success stories they had was with Prop 215 in California, which was a ballot initiative to legalize the use of marijuana for those with a physician's prescription. By the late 1980s meagre epidemiological (i.e. hypothesis-forming) studies have shown marijuana may be useful in treating epilepsy, chemotherapy-related nausea, and also as a way to counteract wasting from AIDS, which was pervasive in Northern California at the time. This drove activists to seek Lindesmith Center's support. Since Dr Nadelmann worried a downvote for the proposition would add to the narrative that marijuana was unpopular, he solicited Soros for money to conduct a state-wide survey on marijuana attitudes to see if the proposition had legs. To their surprise it did, and so the Center aggressively backed the initiative to get it on the 1996 election ballot, which passed and decriminalized medicinal marijuana. Through this initiative the goal of severing the connection between cocaine and marijuana in people's minds was achieved by re-framing the marijuana debate in terms of medicine.

In spite of this victory, as the crack epidemic began to decline more police resources were turned toward marijuana again, although this time around the punishments were much more lenient. The arrests for possession became increasingly the subject of scrutiny for civil rights groups also.

The Lindesmith Center merged with the Drug Policy Foundation (a DC-based reform organization) to for the Drug Policy Alliance, into which George Soros funded more than a $100 million dollars over the course of the 2000s; a representative of his when asked for comment by the author framed the contributions in terms of protecting marginalized populations and vulnerable individuals.

Alongside the increasing racialization of the issue in the public consciousness were more claims on marijuana's medicinal properties. One NGO founder even said they would prefer their children to smoke marijuana instead of imbibe alcohol, saying that in the end the ideal goal would be for marijuana to be cheaper and "significantly more available than alcohol or pills."

In spite of the rosy view given by activists, most doctors were reticent about prescribing medical marijuana, as a lot of the scientific evidence itself was weak and doctors were normally very conservative about experimental treatments. This resulted in a relative minority of doctors writing the vast majority of marijuana prescriptions. NORML did have a registry of doctors who were willing to prescribe medical marijuana; in California this number was 1500 vs the 100,000 physicians in total in the state.

While the amount of marijuana users has never been particularly high, the roll-out of marijuana as a medicinal industry created an entrenched economic interest further provided funding to support wider advocacy for full legalization. This positive feedback loop between industry and drug reform NGOs has ended up supporting the wave of medicinal and full legalization of the 2010s. Another silver lining to the issue was that it had near bipartisan support from the public, compared to more contentious issues such as abortion, immigration, or left wing authoritarianism and violence, making it a safe schilling point for politicians to campaign on. Often times argument for legalization was couched in terms of right-wing talking points, such as providing additional tax base to keep taxes lower for others, or to help clear out red tape. As of 2020 marijuana is fully legal in 14 states, and medicinal marijuana is authorized in 48, and shows only signs of further liberalization.

Between the notions of addressing racial inequality, draconian punishments, and medical uses for cancer and AIDS, the author infers that the main strategy used to advocate for the decriminalization and gradual legalization of marijuana was to make the topic of marijuana about literally anything other than the actual reason the vast majority of users take it, which is to get high.

Psychosis and Schizophrenia

In 2017 the US National Academy of Medicine issued a 468 page report composed of the work of 16 professors and doctors and 13 understudies to compose a meta-analysis of the health effects of cannabis. They found it did not seem to be linked to lung cancer, but the mental health effects were a different story.

The usual response given to this by cannabis advocates is arguing that cannabis use did not correlated with psychosis or other psychiatric illnesses. This is a response that, according to the author, leans heavily on the generally poor epidemiological data which exists for psychosis and schizophrenia. Neither the National Institute of Mental Health, the Center for Disease Control, nor the states themselves track the prevalence of psychosis or schizophrenia. No definite and objective test exists for schizophrenia or psychosis, often simply observations or self-assessments.

The limited data which does exist is provocative. In the US, between 2006 and 2014 emergency rooms had a 50 percent increase of admissions with a primary diagnosis of psychosis. Those with a primary diagnosis of psychosis and secondary diagnosis of cannabis abuse tripled in this period, up to 90,000. Eleven percent of those diagnosed with psychosis also had the cannabis abuse diagnosis, and according to primary research done by the author and a colleague the vast majority of those had no other drug problems diagnosed other than marijuana. Studies from Denmark and Finland showing increases in mental illnesses including schizophrenia and psychosis. The latter cited this 2011 paper, which I quote below:

A lot of the earlier studies linking marijuana with psychosis and schizophrenia in the 1980s were dogged by the criticism that correlation does not equal causation, and many critics brought up the possibility that those with genes or environments more predisposed to cause psychosis or schizophrenia may also simply make a person more predisposed to marijuana use. Another explanation was that marijuana was being used by psychologically deteriorating individuals to self-medicate, but this was more readily dismissed by clinical observations that those in psychiatric care got their symptoms under control suffered relapses if they returned to marijuana use.

A large prospective study out of Dunedin in New Zealand, published in 2002, tracked children born in 1973 every couple of years (up to their middle age adult years) for their mental health status, drug use, and criminality. They found that "people who used cannabis at age 15 were more than 4 times as likely to develop schizophrenia or schizophreniform syndrome as those who never used. Even after accounting for those who had shown psychotic symptoms at age 11, the risk remained threefold higher." This study was noteworthy for putting to bed the idea that schizophrenics were simply self-medicating due to marijuana use.

Time Lag in the Development of Psychosis and Schizophrenia

What was also interesting was that the research showed people developing psychosis and later schizophrenia after people were well into their thirties, which is unusual for both illnesses which have typically have onsets in early adulthood. Advocates have backpedalled to saying that marijuana only accelerates the development of psychosis or schizophrenia and isn't an independent causal factor to it. The data does not bear that out.

Cannabis in the UK and Europe vs United States

In the UK the awareness of marijuana's effects of mental illness were kept more in the public eye by the psychiatrist Sir Robin MacGregor Murray, who, in spite of the lack of professional interest his education paid to marijuana (calling it an "entirely safe drug"), began to see more and more connections between cannabis and psychosis and schizophrenia. After becoming the head of the Institute of Psychiatry at King's College in London he was in an advantageous position to conduct research and reviews and raise awareness, which he did all throughout the 2000s - eventually becoming the most cited schizophrenia researcher in Europe and receiving a knighthood.

Since 2000 cannabis in the UK moved down the list of drug schedules to what was effectively decriminalization in 2004. In spite of all this the marijuana use in the UK did not increase at the rates that it was in Canada (another country which decriminalised in the early 2000s) and the US, and still lags behind them both to this day. The author links this directly to the much more widely disseminated awareness of the links between marijuana , psychosis, and schizophrenia, since the amount of adults in favor of decriminalization actually DECREASED over the 2000s from over 50 percent to about one third in 2010, increasing over the 2010s but still remaining below 50 percent. Cannabis use itself fell from 10 percent for adults and ~30 percent for young adults to 6 percent for adults and ~17 percent for young adults. In spite of this (or because of this) Murray and the Institute of Psychiatry has been the target of a lot of character assassination by the cannabis law reform group CLEAR, accusing he and them in 2015 of confusing correlation with causation (starting to see a pattern?) or even financially benefiting from cannabis prohibition.

Unfortunately knowledge of the connection between marijuana and psychosis has had a difficult time crossing the Atlantic Ocean to the United States. Part of this was due to different approaches; European psychiatry tends to focus more on epidemiology and finding trends and causal associations between behaviors and outcomes, whereas American psychiatry is more focused on neuroimaging and finding exactly how an exposure alters neuronal functioning. In the marijuana field this has led to psychiatrists ceding discussion of the issue to marijuana advocates in the US. It should come as no surprise that most of information about marijuana's mental health effects come out of Europe:

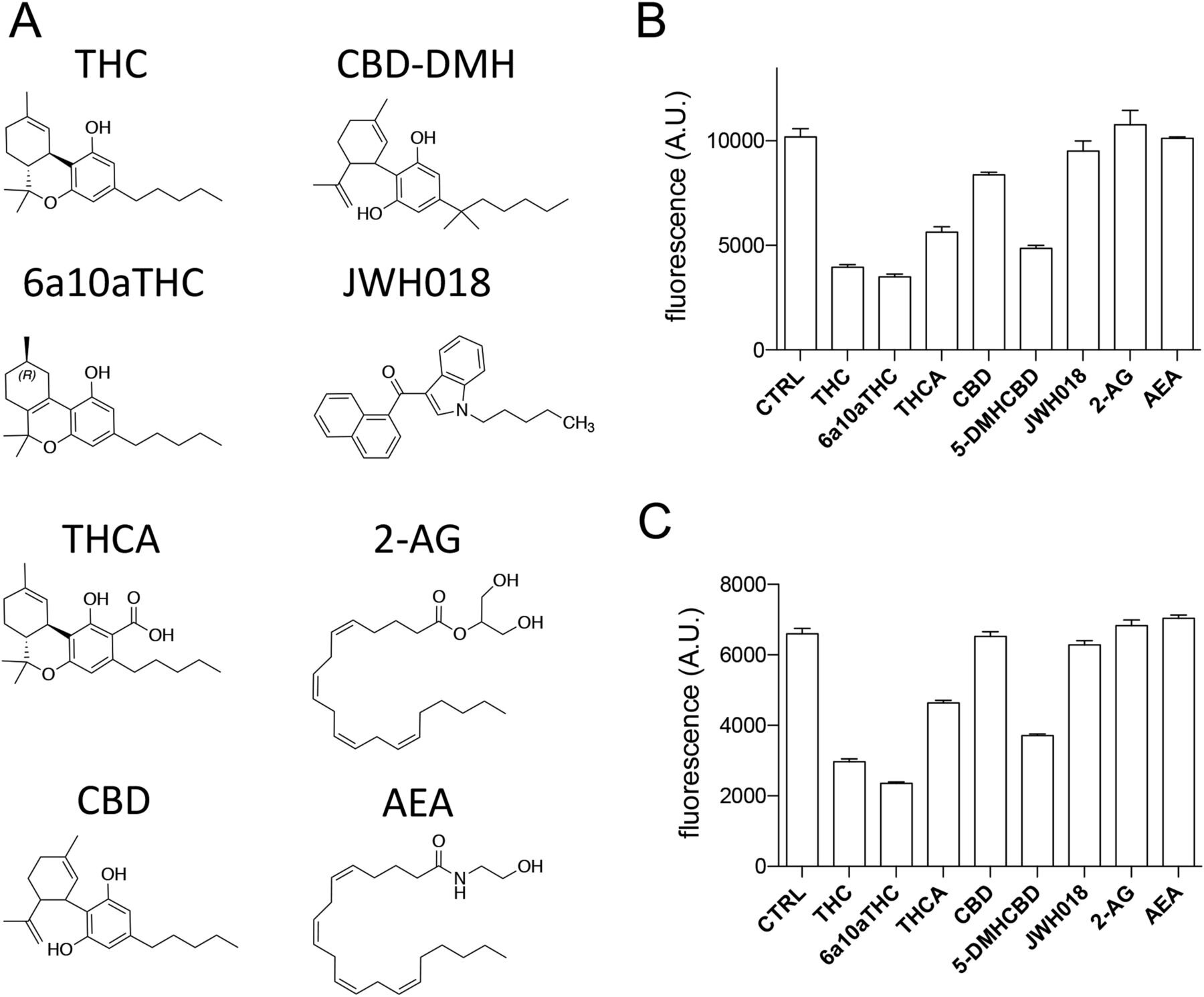

One area of research in which the US was ahead was in the creation of synthetic cannabinoids. Some of these were developed for weight loss (blocking the CB1 receptor) but these were taken off the markets by 2008 due to depressive side effects like anxiety, depression,and suicidal thinking. Another class of cannabinoids (CB1 agonists) were synthesized as ways to test the CB1 receptor, but which eventually made their way into clandestine labs and corner store outlets as a cheap way to get high while passing drug toxicology screenings (at least for awhile). These novel synthetics were often sprayed onto cannabis for additional potency, and led to several high profile cases of psychotic breaks leading to permanent juries (a graduate student with no history of mental illness kept his hand on a stove element to the cost of his right arm), as well as one 5-person homocide where a man killed five of his children (age range: 1 to 8), and the like. The use of these synthetics peaked around 2015, after being explained away on purist grounds that these CB1 agonists were NOT cannabis. The inconvenient fact is that most of these synthetic were phased out in favor of pure THC extracts, which only seems to stimulate the CB1 receptor. Tragedies like this are something advocates for THC and cannabis ignore at the risk to communities by not educating the public properly on the mental health risks.

This series of anecodes were, I thought, poignant:

Touching on the Opiate Crisis

One line of argument used by advocates early in the 2010s was the notion that marijuana use could reduce dependency on opiates, in part because marijuana is alleged to have analgesic properties (alcohol also has analgesic properties). This originated in a publication in 2014 by JAMA Internal Medicine claiming that in a survey of states conducted by Dr. Marcus Bachhuber that those with legalized marijuana had a 25 percent reduction in opiate overdoses throughout the 2000s. One major problem with this study was that very few people registered with the study in the first two years of the study (just 94 in Colorado): the time period where the negative correlation was found to be strongest. This is an issue a lot of statistical analysis can face at times called regression to the mean, where the results of a small sample size are cited as evidence of a trend in a broader population instead of properly seen just as an artifact of that small population's idiosyncracies.

The information collected by Dr. Sanford Gordon of New York University also failed to replicate the findings of Bachhuber. The author and Dr. Gordon compiled epidemiological data on marijuana use, cocaine use, and overdose death rates from 1999 to 2016 from databases of the CDC and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The published conclusions were that

Aside from these studies, the higher amount of opioid overdoses per capita in the United States and Canada compared the the UK lines up with the increased marijuana use in North America as well, although nation-wide studies are fraught with all sorts of confounding variables. Opiate overdoses began to increase in the 1990s, well before the major resurgence in interest in marijuana advocacy. But it still makes you wonder. In any case, without further education on the mental and physical health risks presented we can only expect marijuana use to increase until a breaking point is reached and there is blowback, similar to how Mexico originally introduced prohibition.

(continued in part 2)

After devouring the book I wanted to share some of the information in it on here, because it provides some very hard facts and information about an issue which has bad societal consequences and which has received almost no pushback from the public, at least in North America where I live.

From his website:

An eye-opening report from an award-winning author and former New York Times reporter reveals the link between teenage marijuana use and mental illness, and a hidden epidemic of violence caused by the drug—facts the media have ignored as the United States rushes to legalize cannabis.

Recreational marijuana is now legal in nine states. Almost all Americans believe the drug should be legal for medical use. Advocates argue cannabis can help everyone from veterans to cancer sufferers. But legalization has been built on myths– that marijuana arrests fill prisons; that most doctors want to use cannabis as medicine; that it can somehow stem the opiate epidemic; that it is not just harmless but beneficial for mental health. In this meticulously reported book, Alex Berenson, a former New York Times reporter, explodes those myths:

• Almost no one is in prison for marijuana;

• A tiny fraction of doctors write most authorizations for medical marijuana, mostly for people who have already used;

• Marijuana use is linked to opiate and cocaine use. Since 2008, the US and Canada have seen soaring marijuana use and an opiate epidemic. Britain has falling marijuana use and no epidemic;

• Most of all, THC—the chemical in marijuana responsible for the drug’s high—can cause psychotic episodes. After decades of studies, scientists no longer seriously debate if marijuana causes psychosis.

Psychosis brings violence, and cannabis-linked violence is spreading. In the four states that first legalized, murders have risen 25 percent since legalization, even more than the recent national increase. In Uruguay, which allowed retail sales in July 2017, murders have soared this year.

Berenson’s reporting ranges from the London institute that is home to the scientists who helped prove the cannabis-psychosis link to the Colorado prison where a man now serves a thirty-year sentence after eating a THC-laced candy bar and killing his wife. He sticks to the facts, and they are devastating.

With the US already gripped by one drug epidemic, this book will make readers reconsider if marijuana use is worth the risk.

Reviews

- “[Alex Berenson] has a reporter’s tenacity, a novelist’s imagination, and an outsider’s knack for asking intemperate questions. The result is disturbing.” (―Malcom Gladwell The New Yorker)

- “Takes a sledgehammer to the promised benefits of marijuana legalization, and cannabis enthusiasts are not going to like it one bit.” (―Mother Jones)

- “A brilliant antidote to all the…false narratives about pot out there.” (―American Thinker)

- “An intensively researched and passionate dissent from the now prevailing view that marijuana is relatively harmless.” (―The Marshall Project)

- “Berenson has done an important public service…[Tell Your Children] could save a few lives.” (―The Guardian)

- “The stakes are high…aren’t we better off listening to Berenson than to some marijuana magnate?” (―The Spectator)

- “An interesting book that should be read by all concerned.” (―The Washington Times)

- “Filled with statistics that shock.” (―The Times of London)

The book broadly covers three topics The first covers the modern history of cannabis, starting with Mexico and India in the 19th century and leading up to the recent round of legalization of the 2010's in the United States. The second studies the found connections between marijuana, psychosis, and schizophrenia, also touching on the opioid epidemic. The final part talks about the links between psychosis/schizophrenia and brutal, senseless violence, and how these and other types of crime are increasing disproportionately in places where marijuana is legal. The author brings a lot of studies on each occasion, and they are sobering. The anecdotes about some of the brutal assaults and murders can be rough to read also, so fair warning.

THE HISTORY OF MARIJUANA

Despite being new to European society and the New World (mostly introduced via the importation of hemp for fiber) marijuana was known throughout most of Asia historically. The oldest recorded reference the the effects of cannabis are in the Chinese pharmacopia called the Pen-ts'ao Ching, written as early as 100 AD, which warned that excessive cannabis consumption caused one to "see spirits."

India

In India, hemp was farmed and traded in heavily by the British, which paid little attention to cannabis in general in the early days of Indian colonisation until the establishment of mental institutions in India in the 1800s and the record-keepers there began to see patterns and connections between ganja and institutionalization of its users by friends or family members. In 1873 the government published survey results finding an increase in insanity and insanity-linked violence due to its habitual use, and recommended higher taxes to discourage consumption.

A later report in 1893, spurred by a British politician concerned about the effects of marijuana, instead concluded that the link was not strong, and therefore was fine to be kept as a taxed and regulated industry. While this report was hailed as a breakthrough in marijuana scholarship by activists, there were several flaws in it. In India, cannabis had three traditional modes of consumption. The first is called bhang, which is a cannabis paste blended into milkshakes and consumed during festivals. The psychoactive potency of these is quite low. Then there is ganja and chara, which in the west are known as the bud and hashish forms of marijuana respectively. These had much higher potency and its users tended to be much heavier, daily users; they were also universally looked down upon by traditional Indian society in ways very similar to how western society stereotypes potheads. And it was these individuals who tended to make up the bulk of those admitted to institutions for drug-induced insanity or violence. Of the British commissioners who approved the report to inform state policy, there were three Indians; two of those three opposed the findings. One of them named Nihal Chand (Punjab Lawyer) published a scathing critique of the study's failures to distinguish between the different types of cannabis consumed. In retrospect what was seen as a victory for social liberalism could instead be seen as the British profiting off of the societal ills that some modes of marijuana consumption produced.

In reality, statistics consistently showed that 20 to 30 percent of asylum patients were ill because of cannabis, he wrote. Chand also noted that about 20 percent of the “criminal lunatics” in the Bengal asylums had a diagnosis of cannabis-related insanity, far more than those whose mental illness was attributed to alcohol or opium. He quoted doctors, police officers, and judges—both Indian and British—who linked the drug to violent crime.

Even after the commission report, other doctors working with mental patients would continue to come forth about how a certified lunatic's friends, relatives, and even the patient him or herself would admit to and blame cannabis. People would improve after being off the drug, leave, relapse, and be re-admitted with regularity, and with symptoms which today would be readily classifiable as psychosis. Twenty percent of those classified as criminal lunatics had their violence linked to cannabis use also. What was striking was that the violence was often unprovoked, against family members and strangers alike. One does not need to be a psychiatrist to know that those in psychosis are dangerous individuals. Everyone knows to avoid the dishevelled man whose every other word is a swear word and whose every other sentence is about God.

Mexico

Contrasting India (a Hindu British colony of 330 million people with a long history of cannabis use) is Mexico; in the 19th century it was Catholic, recently independent, and had 13 million people and a native population that was new to cannabis but familiar with other psychoactive plants such as peyote and salvia. It was not a major industry, and was used mostly by soldiers and the poor.

In spite of all these cultural differences, doctors in Mexico in the 1800s also noticed a link between marijuana use, insanity, and violence. This was a finding reported by a University of Cincinnati professor Isaac Campos in 2012 in a history called Home Grown: Marijuana and the Origins of Mexico's War on Drugs. This was a critical work because it exploded the myth that some activists and scholars have perpetuated in the United States, blaming the US prohibition for Mexico's war on drugs. The truth is that Mexico banned the sale of marijuana long before it became a subject of interest to narcotics control policy-wonks in the US and Europe.

Leading up to this were increasing bouts of violence, and increased defense pleas linked to marijuana-induced insanity. One of the highest profile cases was an incident in which the governor of Mexico city claimed that he murdered a political rival "under the influence," as we say today.

Poor Mexicans were more likely to smoke marijuana than the wealthy. But fear of the drug did not stem from class prejudice. Poorer Mexicans were also concerned about marijuana’s effects. The negative attitude toward cannabis was striking because people in Mexico had experience with psychotropic plants, including peyote and salvia, a type of sage that can produce hallucinations. They had no cultural reason to view marijuana negatively.

Yet they did. As marijuana’s use spread, Mexicans viewed it as different from other drugs. It didn’t merely cause users to hallucinate, like other psychotropics. Or excite them, like cocaine. Or disinhibit them, like alcohol. Instead, especially in large doses, it produced all three effects at once. It led to a delirium indistinguishable from insanity and often accompanied by violence. Newspapers regularly referred to criminals “as either a madman or a marihuano,” Campos wrote.

The most potent type was called sinsemilla (i.e. "without seed"), and was estimated to be around 10% THC.

United States (1900 to 1979)

As the fears about marijuana in the United States increased throughout the 1910s and 1920s, with more local and state-wide laws restricting its sale coming into effect, the first federal law restricting the drug was passed in 1937 and imposed a $100/oz tax on marijuana for purposes other than very limited industrial or medicinal use. One character which gets bandied about a lot in this time period was Harry J. Anslinger, who was the commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. He created reports on some highly publicized incidents of violence caused by perpetrators supposedly in the throes of a marijuana psychosis. The evidence of marijuana's connection to violence was a lot weaker then than it was today, ironically. One of the casualties of this time was the hemp industry. At the time THC was not yet discovered, and so it was not possible to gauge the psychoactive properties of a hemp plant scientifically. Anslinger like many of the time was also openly racist, which is fact heavily exploited by advocates to retroactively malign opposition to marijuana as of racist origin.

Around the time of its prohibition, the percentage of Americans who tried marijuana was still in the single digits. Once the counter-cultural movement (psyop) picked up, that increased to 12 percent by 1973; for those 18 to 24 it was 50 percent. It was around this time that advocacy for legalization became more common. The flagship for this was the magazine High Times, published by Tom Forcade. His rational that High Times could be a beachhead for more liberal attitudes toward a vice traditionally looked down upon, similar to how Playboy was for pornography. Alongside this cultural operation was the advocacy group National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), founded by a young Indiana lawyer in 1970 named Keith Stroup, who was even financially backed by Hugh Hefner.

A lot of the strategy around this time in history revolved around reducing the sentences for marijuana consumption. Some of the most draconian laws existed in Texas, where one could get 9 years in jail for smoking marijuana. By 1973 possession was a felon in only two states, although a misdemeanor offense could still give someone a year in jail. And the amount of arrests increased twenty-fold between 1965 and 1973 with increased use of the drug. So at this point it began to have a larger impact on middle class white families, and the full impact of these types of laws were brought to bear more in the public consciousness, making them receptive to the message of reform. Oregon ended up being the first state to decriminalize in 1973, with four more states following two years later.

In addition to the harsh legal penalties, another factor contributing to the loosening of marijuana laws was the fact that it did not seem as dangerous as the forbears of the marijuana issue in the US made it out to be. People were not committing the heinous and senseless crimes of marijuana-induced psychosis dubbed "reefer madness."

The reason for this was quite simple. The weed imported en masse from Mexico was often of extremely cheap quality, even intermixed with seeds and other weeds. With the discovery of THC in 1967, testing found that US marijuana was rarely over two percent THC, with some measures even dipping below one percent. For reference today, any cannabis plant with less than 0.3 percent HTC is considered a hemp plant. To compare this to the Indian classifications, the majority of Americans smoking pot around this time were consuming the equivalent of bhang, which causes a mild buzz after consuming a lot. A group would need to share fifty joints in order for each smoker to receive 25 - 50 mg THC. This fact led to the common enough trope that people "didn't feel anything" after smoking a joint with friends. Mexican sinsemilla at the time was prohibitively expensive in the US ($400/oz pre-inflation).

Contrasting this is today's marijuana, which is normally 20 - 25 percent THC. A single joint delivers more than 100 mg of the drug: far more potent than anything the Mexicans had access too back in the 19th century. This moves modern marijuana use more toward the category of ganja or chara, which was often implicated as a cause of psychosis or worsening schizophrenia or bipolar disorder for those institutionalized.

Amusingly enough, on the heels of this decriminalization was the growth of the drug paraphenalia trade, which even had its own trade association. This group became increasingly notorious as the perception became more common they were marketing drug paraphernalia to minors. This led to a backlash by parents, which were becoming increasingly aware of the effects of the drug on their children, especially habitual users.

On top of this was a scandal in 1977 involving Dr Peter Bourne (President Jimmy Carter's drug policy advisor) who had in fact was discovered to have used both marijuana and cocaine with Keith Stroup (of NORML); this telegraphed the notion loudly that the biggest advocates for legalization were just interested in getting high. This scandal, fueled by the "gateway drug" hypothesis from the 1950's was a lightning bolt to the American consciousness and instantly associated marijuana with cocaine, the use of which in 1979 had tripled since 1972. Stroup eventually resigned from NORML a year later and the movement to decriminalize marijuana went into hibernation until the 1990s.

United States (1980 - present)

In spite of acute awareness of the harm of cocaine, its use continued to spread due to decreasing prices. Following this was the rise of crack (cocaine baked with baking soda and water into a smokeable pellet). This trend led to a rising tide of crime and violence in the US, rising 41 percent from 1983 to 1991. The number of dead was almost half of the amount of American men killed in Vietnam over the course of the war. Alongside this was the explosion in AIDS among gay men and heroin users. During this time marijuana use continued to decline.

Dr Ethan Nadelmann, a 1979 Harvard graduate in the law-PhD program, viewed the source of all these problems with violence as prohibition, drawing analogies between the current drugs in vogue and alcohol. Throughout the 1980's he fought an uphill battle to get greater recognition for the problems prohibition created, while toning down rhetoric about the legalization of the drugs themselves. After a fortuity lunch with the billionaire investor George Soros he received financial backing to advocate for the liberalization of the drug laws in the United States and elsewhere. With this backing he founded the Lindesmith Center (named after a sociologist who was also an advocate for decriminalization) to advocate for drug policy reform.

One of the first success stories they had was with Prop 215 in California, which was a ballot initiative to legalize the use of marijuana for those with a physician's prescription. By the late 1980s meagre epidemiological (i.e. hypothesis-forming) studies have shown marijuana may be useful in treating epilepsy, chemotherapy-related nausea, and also as a way to counteract wasting from AIDS, which was pervasive in Northern California at the time. This drove activists to seek Lindesmith Center's support. Since Dr Nadelmann worried a downvote for the proposition would add to the narrative that marijuana was unpopular, he solicited Soros for money to conduct a state-wide survey on marijuana attitudes to see if the proposition had legs. To their surprise it did, and so the Center aggressively backed the initiative to get it on the 1996 election ballot, which passed and decriminalized medicinal marijuana. Through this initiative the goal of severing the connection between cocaine and marijuana in people's minds was achieved by re-framing the marijuana debate in terms of medicine.

In spite of this victory, as the crack epidemic began to decline more police resources were turned toward marijuana again, although this time around the punishments were much more lenient. The arrests for possession became increasingly the subject of scrutiny for civil rights groups also.

Civil libertarians and liberal groups focused on the fact that African Americans were arrested two to three times as often as whites, though the two groups had similar rates of marijuana use. (The groups skimmed over the fact that “similar” didn’t mean the same; federal surveys showed that African Americans used marijuana somewhat more than whites, and those black people who did use tended to be heavier smokers. A 2016 paper in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence that was based on federal surveys covering more than 340,000 people showed that black people were almost twice as likely to report marijuana abuse or dependence as whites.)

The Lindesmith Center merged with the Drug Policy Foundation (a DC-based reform organization) to for the Drug Policy Alliance, into which George Soros funded more than a $100 million dollars over the course of the 2000s; a representative of his when asked for comment by the author framed the contributions in terms of protecting marginalized populations and vulnerable individuals.

Alongside the increasing racialization of the issue in the public consciousness were more claims on marijuana's medicinal properties. One NGO founder even said they would prefer their children to smoke marijuana instead of imbibe alcohol, saying that in the end the ideal goal would be for marijuana to be cheaper and "significantly more available than alcohol or pills."

In spite of the rosy view given by activists, most doctors were reticent about prescribing medical marijuana, as a lot of the scientific evidence itself was weak and doctors were normally very conservative about experimental treatments. This resulted in a relative minority of doctors writing the vast majority of marijuana prescriptions. NORML did have a registry of doctors who were willing to prescribe medical marijuana; in California this number was 1500 vs the 100,000 physicians in total in the state.

California didn’t keep a mandatory registry of its patients, but surveys showed they were mostly white, under 45, and had been regular cannabis users before getting a medical card. Pain was a far more frequent reason for authorization than cancer or other serious illnesses. By 2014, some physicians charged as little as $30 for an authorization. Even medical marijuana supporters complained that the process was a joke.... The situation was similar [in Oregon] and elsewhere... other states had even looser rules (not requiring a physician's authorization).

While the amount of marijuana users has never been particularly high, the roll-out of marijuana as a medicinal industry created an entrenched economic interest further provided funding to support wider advocacy for full legalization. This positive feedback loop between industry and drug reform NGOs has ended up supporting the wave of medicinal and full legalization of the 2010s. Another silver lining to the issue was that it had near bipartisan support from the public, compared to more contentious issues such as abortion, immigration, or left wing authoritarianism and violence, making it a safe schilling point for politicians to campaign on. Often times argument for legalization was couched in terms of right-wing talking points, such as providing additional tax base to keep taxes lower for others, or to help clear out red tape. As of 2020 marijuana is fully legal in 14 states, and medicinal marijuana is authorized in 48, and shows only signs of further liberalization.

Between the notions of addressing racial inequality, draconian punishments, and medical uses for cancer and AIDS, the author infers that the main strategy used to advocate for the decriminalization and gradual legalization of marijuana was to make the topic of marijuana about literally anything other than the actual reason the vast majority of users take it, which is to get high.

MENTAL HEALTH EFFECTS OF MARIJUANA

Psychosis and Schizophrenia

In 2017 the US National Academy of Medicine issued a 468 page report composed of the work of 16 professors and doctors and 13 understudies to compose a meta-analysis of the health effects of cannabis. They found it did not seem to be linked to lung cancer, but the mental health effects were a different story.

The committee found strong evidence that marijuana causes schizophrenia and some evidence that it worsens bipolar disorder and increases the risk of suicide, depression, and social anxiety disorder. “Cannabis use is likely to increase the risk of developing schizophrenia and other psychoses; the higher the use, the greater the risk,” the scientists concluded.

The higher the use, the greater the risk. In other words, marijuana in the United States has become increasingly dangerous to mental health in the last fifteen years, as millions more people consume higher-potency cannabis more frequently.

The usual response given to this by cannabis advocates is arguing that cannabis use did not correlated with psychosis or other psychiatric illnesses. This is a response that, according to the author, leans heavily on the generally poor epidemiological data which exists for psychosis and schizophrenia. Neither the National Institute of Mental Health, the Center for Disease Control, nor the states themselves track the prevalence of psychosis or schizophrenia. No definite and objective test exists for schizophrenia or psychosis, often simply observations or self-assessments.

The limited data which does exist is provocative. In the US, between 2006 and 2014 emergency rooms had a 50 percent increase of admissions with a primary diagnosis of psychosis. Those with a primary diagnosis of psychosis and secondary diagnosis of cannabis abuse tripled in this period, up to 90,000. Eleven percent of those diagnosed with psychosis also had the cannabis abuse diagnosis, and according to primary research done by the author and a colleague the vast majority of those had no other drug problems diagnosed other than marijuana. Studies from Denmark and Finland showing increases in mental illnesses including schizophrenia and psychosis. The latter cited this 2011 paper, which I quote below:

The increase in comorbid cannabis-specific SUDs across the two cohorts in this study is of particular interest due to the controversial nature of the relationship between cannabis use and psychosis. Historical [31] and birth cohort studies [32,33] have both found cannabis usage to precede psychotic symptom onset. There has also been a growing body of evidence to suggest an association between cannabis use and heightened risk of a psychotic illness, with heavier use posing an even greater risk [10]. The dose–response effect is particularly important due to the escalation in potency of the drug and the development of more sophisticated, indoor, hydroponic growing techniques introduced in England in the early 1990s [34,35].

A lot of the earlier studies linking marijuana with psychosis and schizophrenia in the 1980s were dogged by the criticism that correlation does not equal causation, and many critics brought up the possibility that those with genes or environments more predisposed to cause psychosis or schizophrenia may also simply make a person more predisposed to marijuana use. Another explanation was that marijuana was being used by psychologically deteriorating individuals to self-medicate, but this was more readily dismissed by clinical observations that those in psychiatric care got their symptoms under control suffered relapses if they returned to marijuana use.

A large prospective study out of Dunedin in New Zealand, published in 2002, tracked children born in 1973 every couple of years (up to their middle age adult years) for their mental health status, drug use, and criminality. They found that "people who used cannabis at age 15 were more than 4 times as likely to develop schizophrenia or schizophreniform syndrome as those who never used. Even after accounting for those who had shown psychotic symptoms at age 11, the risk remained threefold higher." This study was noteworthy for putting to bed the idea that schizophrenics were simply self-medicating due to marijuana use.

Time Lag in the Development of Psychosis and Schizophrenia

Marijuana users generally start smoking between 14 and 19; first-time psychotic breaks most often occur from 19 to 24 for men, 21 to 27 for women. In other words, almost no one develops a permanent psychotic illness the first time he uses marijuana—or even after a few months. The gap between when people start smoking and when they break averages six years, according to a 2016 paper in the Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry that examined previous research. The Finnish paper showing that almost half of cannabis psychosis diagnoses convert to schizophrenia within eight years is more evidence of the time lag. A problem that seems temporary becomes permanent.

The time lag is crucial. It implies that the 1990s increase in cannabis use—and the increase in potency that began then and continues today—wouldn’t have immediately affected psychosis rates. Instead, if marijuana slowly drives some people into permanent psychosis, rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders might have trended higher in the 2000s, with the increase visible after 2010.

That trend is exactly what some research has found.

....

[According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality the] number of people arriving at emergency rooms with marijuana-related problems has soared in the last decade. In 2014, the most recent year for which full data is available, emergency rooms saw more than 1.1 million cases that included a diagnosis of marijuana abuse or dependence—up from fewer than 400,000 in 2006.... Cases involving marijuana rose far faster than those involving cocaine—and even faster than those involving opiates. In 2006, cannabis cases were less common than the other two drugs. By 2014, they were more common than opiates and twice as common as cocaine. Only alcohol, which is far more widely used, contributed to more emergency visits.

...

Besides the huge increase in marijuana use disorder, the database showed a big rise in psychosis-related cases. In 2006, emergency rooms saw 553,000 people with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder with psychosis, or other psychosis. By 2014, that number had risen almost 50 percent, to 810,000. Including cases where psychosis was either a primary or secondary diagnosis, the increase was even faster, from 1.26 million in 2006 to almost 2.1 million in 2014.

....

In 2006, about 30,000 emergency room patients had a primary diagnosis of psychosis and a secondary marijuana use disorder. Eight years later, that number had almost tripled, to nearly 90,000. Put another way, every day in 2014 almost 250 people showed up at emergency rooms all over the United States with psychosis and marijuana dependence. They accounted for more than 10 percent of all the cases of primary psychosis in emergency rooms. Most of those patients had problems only with cannabis, not other drugs, our analysis found.

Marijuana disorder was also associated with more severe psychosis—as measured by being hospitalized instead of released following emergency treatment. Psychotic patients with a marijuana sub-diagnosis were about twice as likely to wind up hospitalized as those who didn’t have one.

Finally, the emergency room data showed that marijuana dependency was linked to opiate and cocaine addiction. The number of emergency room patients who had a primary diagnosis of opiate addiction and a secondary diagnosis of marijuana use disorder nearly tripled between 2006 and 2014—more evidence that the theory that marijuana can help people stop using opiates is dangerously wrong. (more on this later)

What was also interesting was that the research showed people developing psychosis and later schizophrenia after people were well into their thirties, which is unusual for both illnesses which have typically have onsets in early adulthood. Advocates have backpedalled to saying that marijuana only accelerates the development of psychosis or schizophrenia and isn't an independent causal factor to it. The data does not bear that out.

Cannabis in the UK and Europe vs United States

In the UK the awareness of marijuana's effects of mental illness were kept more in the public eye by the psychiatrist Sir Robin MacGregor Murray, who, in spite of the lack of professional interest his education paid to marijuana (calling it an "entirely safe drug"), began to see more and more connections between cannabis and psychosis and schizophrenia. After becoming the head of the Institute of Psychiatry at King's College in London he was in an advantageous position to conduct research and reviews and raise awareness, which he did all throughout the 2000s - eventually becoming the most cited schizophrenia researcher in Europe and receiving a knighthood.

Since 2000 cannabis in the UK moved down the list of drug schedules to what was effectively decriminalization in 2004. In spite of all this the marijuana use in the UK did not increase at the rates that it was in Canada (another country which decriminalised in the early 2000s) and the US, and still lags behind them both to this day. The author links this directly to the much more widely disseminated awareness of the links between marijuana , psychosis, and schizophrenia, since the amount of adults in favor of decriminalization actually DECREASED over the 2000s from over 50 percent to about one third in 2010, increasing over the 2010s but still remaining below 50 percent. Cannabis use itself fell from 10 percent for adults and ~30 percent for young adults to 6 percent for adults and ~17 percent for young adults. In spite of this (or because of this) Murray and the Institute of Psychiatry has been the target of a lot of character assassination by the cannabis law reform group CLEAR, accusing he and them in 2015 of confusing correlation with causation (starting to see a pattern?) or even financially benefiting from cannabis prohibition.

Unfortunately knowledge of the connection between marijuana and psychosis has had a difficult time crossing the Atlantic Ocean to the United States. Part of this was due to different approaches; European psychiatry tends to focus more on epidemiology and finding trends and causal associations between behaviors and outcomes, whereas American psychiatry is more focused on neuroimaging and finding exactly how an exposure alters neuronal functioning. In the marijuana field this has led to psychiatrists ceding discussion of the issue to marijuana advocates in the US. It should come as no surprise that most of information about marijuana's mental health effects come out of Europe:

• “Association Between Cannabis Use and Psychosis-Related Outcomes Using Sibling Pair Analysis in a Cohort of Young Adults,” Archives of General Psychiatry , May 2010: 3,801 participants in Australia: Using cannabis beginning at age 15 raised risk of hallucinations by almost 3 times at 21.

• “Linking Substance Use with Symptoms of Subclinical Psychosis in a Community Cohort over 30 Years,” Addiction , 2011: 591 participants in Switzerland: Using cannabis regularly in adolescence raised risk of paranoid ideas such as “Someone else can control my thoughts” by 2.6 times.

• “Substance-induced Psychoses Converting into Schizophrenia: A Register-based Study of 18,478 Finnish Inpatient Cases, Journal of Clinical Psychiatry , January 2013: Almost half of patients hospitalized with cannabis psychosis were diagnosed with schizophrenia within eight years. Psychosis caused by other drugs had lower rates of conversion, with alcohol at 5 percent.

• “Association of Combined Patterns of Tobacco and Cannabis Use in Adolescence with Psychotic Experiences,” JAMA Psychiatry , January 2018: 5,300 participants in England: Teenage cannabis use roughly tripled the risk of psychotic symptoms; tobacco use did not show a risk after adjusting for cannabis use.

• “Adolescent Cannabis Use, Baseline Prodromal Syndromes, and the Risk of Psychosis,” British Journal of Psychiatry , March 2018: 6,534 participants in Finland: Using cannabis more than five times raised the risk of psychotic disorders almost sevenfold; after adjusting for parental psychosis and other variables, cannabis tripled the risk.

One area of research in which the US was ahead was in the creation of synthetic cannabinoids. Some of these were developed for weight loss (blocking the CB1 receptor) but these were taken off the markets by 2008 due to depressive side effects like anxiety, depression,and suicidal thinking. Another class of cannabinoids (CB1 agonists) were synthesized as ways to test the CB1 receptor, but which eventually made their way into clandestine labs and corner store outlets as a cheap way to get high while passing drug toxicology screenings (at least for awhile). These novel synthetics were often sprayed onto cannabis for additional potency, and led to several high profile cases of psychotic breaks leading to permanent juries (a graduate student with no history of mental illness kept his hand on a stove element to the cost of his right arm), as well as one 5-person homocide where a man killed five of his children (age range: 1 to 8), and the like. The use of these synthetics peaked around 2015, after being explained away on purist grounds that these CB1 agonists were NOT cannabis. The inconvenient fact is that most of these synthetic were phased out in favor of pure THC extracts, which only seems to stimulate the CB1 receptor. Tragedies like this are something advocates for THC and cannabis ignore at the risk to communities by not educating the public properly on the mental health risks.

This series of anecodes were, I thought, poignant:

Dr. Melanie Rylander, a psychiatrist in Colorado and assistant professor at the University of Colorado–Denver, said that heavy smokers have extraordinary denial about the drug’s impact. “In eleven years of practicing psychiatry, I have yet to convince anyone that marijuana is causing problems for them,” she said. “A lot of time those conversations are not very productive.”

People with severe mental illness are often so impaired that they lack basic awareness that they are ill, Rylander said. But even people who know something is wrong with their minds rarely connect their symptoms to marijuana. Unlike alcohol, cocaine, or opiates, marijuana rarely causes acute physical crises, she said. Users can tell themselves that their psychiatric problems would have happened anyway.

Dr. Scott Simpson works alongside Rylander in the psychiatric emergency room at Denver Health Medical Center. He said he typically tries to talk around the issue instead of discussing the drug’s dangers directly. “Usually my approach is, ‘Marijuana is great for you, tell me how things are going for you in general,’ ” he said. “ ‘Why is it that you can’t work, why is it that you can’t complete school?’ ”

I could imagine that style working for Simpson. He was friendly and boyish-looking despite the flecks of gray in his hair. Rylander was tall, intense, and angular, but equally thoughtful. Rylander, Simpson, and I were talking in a conference room down a short hallway from Denver Health’s psychiatric ER, which came complete with seclusion rooms where seriously psychotic patients could be restrained to their beds.

Simpson told me of a typical case: a man in his early twenties brought in by his parents. “An immigrant family, they are taking care of him . . . he’s a pretty sick guy, talks to himself. And, by the way, he smokes pot three times a week.”

Marijuana can be “very insidious,” he said. Smokers don’t think of themselves as addicts. But quitting or even cutting back is difficult. Meanwhile, their psychiatric symptoms worsen little by little. “They have anxiety, new symptoms, and they’re smoking pot every day, and it’s much more difficult to tease out.”

I couldn’t help thinking of what George Francis William Ewens had written in the Indian Medical Gazette almost 114 years before:

[quote}There is, however, equally little doubt that any form of the drug produces a violent craving for it, that the amount taken is gradually increased, and that apart from the physical effect a general moral deterioration, as in alcoholism, sooner or latter [ sic ] sets in . . .[/quote}

As I talked to Rylander and Simpson, tens of thousands of people gathered a mile to the north for Denver’s annual Mile High 420 Festival. It was April 20, the unofficial cannabis holiday. Billed as the largest cannabis-themed event that day anywhere in the world, the festival was a free concert at Denver’s Civic Center Park, with Lil Wayne as the headliner. On my way to the hospital, I had walked through lines of people waiting to pass through security screening.... Within a few hours, some of those users would arrive at Denver Health. As Simpson told me later, in the dry language of medicine, the hospital’s medical and psychiatric emergency rooms had “several cannabis-related presentations” that day.

But as Rylander, Simpson, and I spoke, the ward around us was still quiet. Should psychiatrists speak out about what they were seeing to discourage cannabis use, I asked? Simpson said that in Colorado, psychiatrists had tried and failed. “We’ve put it out there, and the community is not receptive.” At this point, his job as a physician was to try to deal with the wreckage, “treat what comes in the door.”

What did he think would happen in five years, I asked? What would the Denver Health emergency room be like, especially if cannabis continued to grow in popularity?

Simpson had a three-word answer: “It’ll be busier.”

Touching on the Opiate Crisis

One line of argument used by advocates early in the 2010s was the notion that marijuana use could reduce dependency on opiates, in part because marijuana is alleged to have analgesic properties (alcohol also has analgesic properties). This originated in a publication in 2014 by JAMA Internal Medicine claiming that in a survey of states conducted by Dr. Marcus Bachhuber that those with legalized marijuana had a 25 percent reduction in opiate overdoses throughout the 2000s. One major problem with this study was that very few people registered with the study in the first two years of the study (just 94 in Colorado): the time period where the negative correlation was found to be strongest. This is an issue a lot of statistical analysis can face at times called regression to the mean, where the results of a small sample size are cited as evidence of a trend in a broader population instead of properly seen just as an artifact of that small population's idiosyncracies.

The information collected by Dr. Sanford Gordon of New York University also failed to replicate the findings of Bachhuber. The author and Dr. Gordon compiled epidemiological data on marijuana use, cocaine use, and overdose death rates from 1999 to 2016 from databases of the CDC and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The published conclusions were that

Not only did findings from the original analysis (of Bachhuber) not hold over the longer period, but the association between state medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality reversed direction from −21% to +23% and remained positive after accounting for recreational cannabis laws. We also uncovered no evidence that either broader (recreational) or more restrictive (low-tetrahydrocannabinol) cannabis laws were associated with changes in opioid overdose mortality. We find it unlikely that medical cannabis—used by about 2.5% of the US population—has exerted large conflicting effects on opioid overdose mortality. A more plausible interpretation is that this association is spurious. Moreover, if such relationships do exist, they cannot be rigorously discerned with aggregate data. Research into therapeutic potential of cannabis should continue, but the claim that enacting medical cannabis laws will reduce opioid overdose death should be met with skepticism.

A July 2017 paper in the Journal of Opioid Management found that medical cannabis laws were associated with a 22 percent increase in age-adjusted opioid-related mortality between 2011 and 2014. Worse, mortality increased as time passed.

“It was surprising for me too, when I ran the numbers and got the results,” said Elyse Phillips, the study’s author. “When you just look at yes or no having a medical marijuana law, there was a correlation with those states having much higher deaths.”

...

An even more worrisome result came from a 2017 study that traced drug use in individuals over time rather than depending on state-level data. Trying to tease out all the factors driving marijuana or opiate use in an entire state is next to impossible. Looking at changes in individual behavior over a period of years is a far better way to determine cause and effect.

So what scientists really needed was a big national survey that asked people about their drug use and then returned to the same people years later.... Dr. Mark Olfson, a psychiatrist at Columbia University who specializes in addiction, realized that he could find the data in a survey initially designed to measure alcohol use. In 2001–2002 and again three years later, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism surveyed 34,000 Americans on their substance use and psychiatric problems.

These studies corroborated previous findings connecting marijuana with heroin use, both as a predictor of opioid use later in life from adolescence and as a predictor of relapse for recovering opioid addicts. Two twin studies out of Australia and the Netherlands in 2003 and 2006 for example found that marijuana users were several fold more likely to develop an opiate or cocaine use disorder than their abstaining twins.

Aside from these studies, the higher amount of opioid overdoses per capita in the United States and Canada compared the the UK lines up with the increased marijuana use in North America as well, although nation-wide studies are fraught with all sorts of confounding variables. Opiate overdoses began to increase in the 1990s, well before the major resurgence in interest in marijuana advocacy. But it still makes you wonder. In any case, without further education on the mental and physical health risks presented we can only expect marijuana use to increase until a breaking point is reached and there is blowback, similar to how Mexico originally introduced prohibition.

(continued in part 2)

Wanting to know what the fuss was all about, I've tried pot on numerous occasions throughout my life, but it has never had any effect on me if I smoke it. Maybe because not being a cigarette smoker, I can't get the hang of the inhale, and end up burning my lungs out or having a coughing fit each time, but I did get it in me. Once I tried a pot-laced brownie (how stereotypical), and the only effect was to make me feel uncomfortably lightheaded and slightly distorted. I can feel basically the same way when my blood sugar gets low, so why would I seek that out otherwise?

Wanting to know what the fuss was all about, I've tried pot on numerous occasions throughout my life, but it has never had any effect on me if I smoke it. Maybe because not being a cigarette smoker, I can't get the hang of the inhale, and end up burning my lungs out or having a coughing fit each time, but I did get it in me. Once I tried a pot-laced brownie (how stereotypical), and the only effect was to make me feel uncomfortably lightheaded and slightly distorted. I can feel basically the same way when my blood sugar gets low, so why would I seek that out otherwise?