The only connection that I was able to find between brain and proanthocyanidins is NAD+.

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

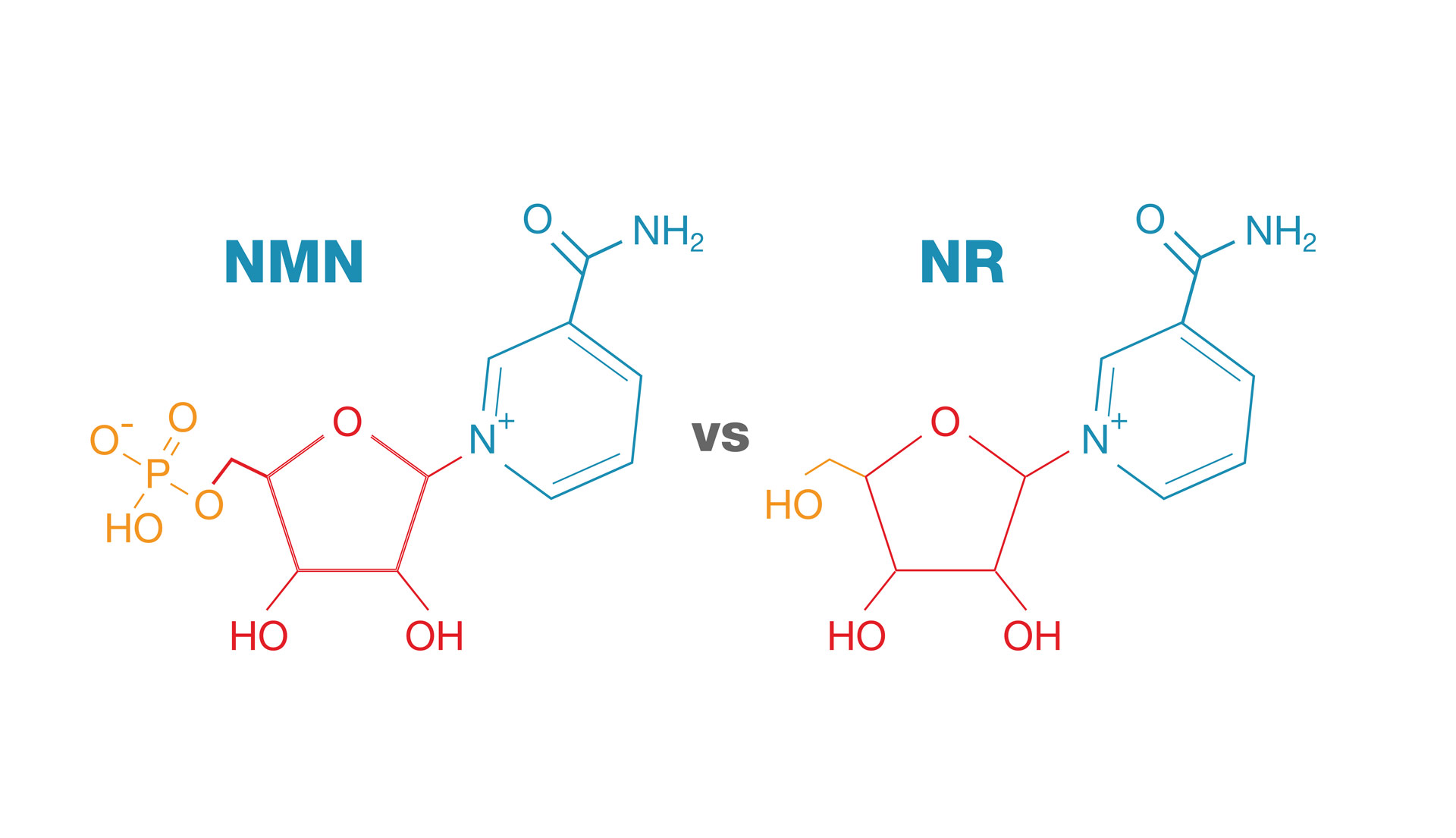

You can also increase NAD+ with NMN and NR.

www.nmn.com

www.nmn.com

You can also get a direct NAD+ treatment.

Dietary proanthocyanidins boost hepatic NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 expression and activity in a dose-dependent manner in healthy rats

Proanthocyanidins (PACs) have been reported to modulate multiple targets by simultaneously controlling many pivotal metabolic pathways in the liver. However, the precise mechanism of PAC action on the regulation of the genes that control hepatic metabolism ...

Grape Seed Proanthocyanidin Extract Moderated Retinal Pigment Epithelium Cellular Senescence Through NAMPT/SIRT1/NLRP3 Pathway

Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cellular senescence is an important process in degenerative retinal disorders. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract (GSPE) alleviates senescence-related degenerative disorders; however, the potential effects of GSPE intake ...

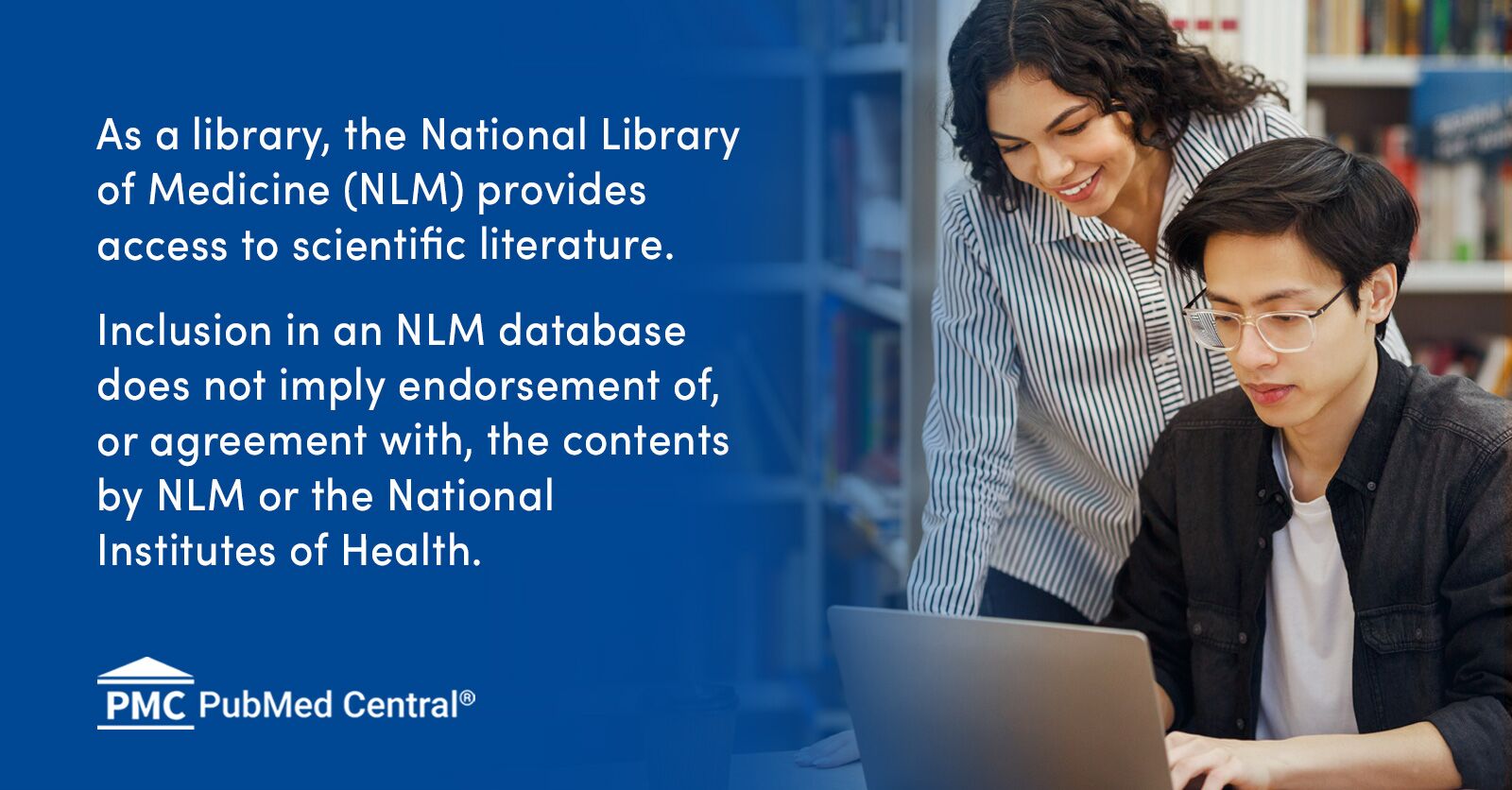

You can also increase NAD+ with NMN and NR.

NMN vs NR: The Differences Between These 2 NAD+ Precursors

Discover details about NMN and NR from their molecular size to their positions in the biosynthesis pathway.

You can also get a direct NAD+ treatment.

I Got a $600 Brain 'Reboot' and It Changed My World

It's good to be skeptical about wonder drugs, because often there's nothing wonderful about them at all. So when a finance worker friend of mine told me he'd discovered a miracle treatment that gives him a huge advantage over his colleagues, I was dubious. "No—I'm full of energy every day and feel like a new person!" he promised. "I don't need to drink eight cups of coffee every day now; this is so much better, and I just get a top up every few weeks!"

I suspected he may have just found out about Modafinil, or one of the other study drugs internet psychonauts have already been using for years. But I was wrong. He sent me a link to a pharmacy in South Kensington offering intravenous "Brain Reboot Infusions," which of course sound far too much like something from Minority Report to be genuinely real. But I decided to give my friend the benefit of the doubt and do a little research anyway.

The main ingredient in the intravenous cocktail is nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, or "NAD+." Discovered in 1906, it's a coenzyme found in all living cells that is "essentially responsible for converting food energy into cellular energy," according to Dr. Mark Collins, consultant psychiatrist at the Priory Hospital, Roehampton.

The internet tells me NAD+ is popular among the "anti-aging community," thanks to a Harvard Medical School study that found it rewound "aspects of age-related demise in mice." It's also supposedly good for: detoxing from alcohol and drugs, increasing energy and focus, reducing chronic fatigue, increasing your metabolism, and improving your cardiovascular health.

It still sounded like bullshit, but the only way I could tell for certain was to put it to the test. I'd quit drinking that particular week, and—as I'd learned online—this treatment could apparently help to mitigate my booze cravings, so the timing was perfect: I booked an appointment for the following day.

Zen Healthcare, just around the corner from Harrods, specializes in the kind of things you might expect a Knightsbridge clinic to specialize in: "bespoke weight loss therapies," travel vaccinations for far-flung locations, botox, "vampire facials," and, of course, Brain Reboot Infusions—which will set you back about $600. (Full disclosure: I got mine for free.)

I arrived a little early, but a Dr. Yassine was there to meet me and explain some of the side effects I might experience while receiving the treatment.

"You will feel your chest tighten and may get a headache," he said. "But this will pass."

I signed some waivers and was escorted to a room where Yassine took my blood pressure. Which, you'll be happy to hear, was normal.

"Are you OK with needles?" he asked.

"Yeah, fine."

Yassine inserted the drip and, a moment later, the "Brain Reboot Cocktail" was flowing through my veins. As he'd warned, I began to feel my chest tighten. Thirty minutes in, I started to wonder what I was doing—my head was aching, the discomfort was becoming kind of alarming, and I was suddenly acutely aware that a foreign substance had by now probably completely flooded my bloodstream. I toyed with the idea of hitting the buzzer Yassine had provided me with should I want to end the treatment, but I decided to stay the course.

Fifty minutes in, I felt a calm sense of positivity envelope my body. Yassine came in and said I had ten minutes left, which flew by. Removing the IV, he asked me how I felt.

"Kinda dreamy," I said.

"A lot of people say similar. Be careful on your way home."

I thanked Yassine more than I needed to. It was time for me to go.

I walked outside, and it hit me: I felt a surge of energy, but no jitters or edginess. My mood had noticeably improved. I felt poised, positive, and pumped-up. I remember thinking, This is awesome, and then saying exactly that out loud. I hopped on the subway, which was as crowded as ever, but for once all the back sweat and the fact it was nearly getting in my mouth didn't bum me out at all.

I woke up the next day at 7 AM and didn't feel horrendous, which is unusual for me. In fact, I felt great. The dreamy feeling had gone, but there was a definite improvement in energy levels, focus, and mindset. This continued throughout the rest of the day, and then for the following eight or so days. But what of its supposed effects on my otherwise unwavering love for beer?

"It's been known for decades that a high dose of vitamin B3—the 'poor man's' way of elevating NAD levels—has a beneficial effect for alcoholics, both in terms of detoxification and, perhaps more importantly, in reducing craving and anxiety levels after detoxification," said Dr. Mark Collins in an email.

And it seems the theory still holds: In all the time I could feel the treatment's effects, I didn't crave the cold embrace of a freshly poured pint even once.

That said, my cravings were just that: cravings. It's not like I was in the midst of a full-blown Stella dependence; I just like alcohol. So to find out how useful NAD+ therapy really is when it comes to drug or alcohol addictions, I asked Dr. Yassine to take me through the theory of how exactly a Brain Reboot Infusion can help someone suffering from withdrawal.

"NAD+ has a significant role in reducing the withdrawal effects by restoring the neurotransmitter balance, which shifts significantly after the drug that's been withdrawn has been removed," he explained. "As a result, the patient experiences almost no withdrawal symptoms whilst and after completing the infusion cycle."

Of course, Dr. Yassine works at a clinic that offers this procedure, so it would make sense for him to talk up NAD+. Still, Dr. Collins—who specializes in addictions and has no real reason to sing the treatment's praises—is also complimentary, if a little cautiously. "I have now witnessed its use in many patients and am very impressed with the short-term results," he said in his email, adding that "what is clearly needed is more research, and in particular longer-term outcome studies."

Dr. Yassine put me in touch with some patients, on the condition of anonymity, to hear how the treatment has worked out for them.

"I've been taking codeine for the last few months," said Jeff*. "It started with a back pain, and I never realized I was going to be hooked up. Then I tried to stop, and it was hell. But having tried NAD+ infusions, stopping codeine has been easier; I didn't feel all the debilitating symptoms I'd experienced earlier."

Ian*, who had been using crack and heroin, had a similar experience.

"I'd be lying if I said the thoughts [about picking up] aren't in my mind, and in my mind often, but that deep 'urge' that addicts will know about isn't there any longer," he said. "I also see a therapist to talk through and figure out why I'm driven to such behaviors, but as of right now, I feel a sense of self-control that I've not felt in a long time. I still have more treatments to go, and I feel I'll always need therapy, but thank God I decided to tell some strangers my deepest problems. Things could have been very different."

Ian's point is important: NAD+ therapy—while seemingly useful, according to everyone I spoke to—is not a panacea. While it may well dull cravings in some patients, it might not for others—and clearly it can't be relied upon exclusively without additional therapy and other forms of treatment.

For me, the treatment did exactly what it said it would, and there are promising signs that it helps with drug and alcohol withdrawal. But as for NAD+'s supposed anti-aging properties, or its ability to improve your metabolism and cardiovascular health, it's very early days. As Dr. Collins pointed out, much more research needs to be done before anything can be said for sure.

I Got a $600 Brain 'Reboot' and It Changed My World

NAD+ therapy can supposedly increase your energy, focus, and metabolism, improve your cardiovascular health, and help you detox from alcohol and drugs. All this, of course, sounds incredibly unlikely—so I thought I'd see for myself.www.vice.com