Sounds produced inside circle would have been less audible to anybody outside, research finds

David Keys

Scientists have succeeded in recreating the soundscape of the inner sanctum of

Stonehenge.

It’s the first time that the acoustics of the world’s most famous prehistoric temple have been accurately experienced for up to 2,000 years.

The main phase of the monument was built in around 2,500BC. Its major period of use lasted until at least 1,600BC. However, it’s likely that some form of ritual or other activity continued there, perhaps intermittently, for at least another one and a half millennia. Then, at some stage, half of the great temple was destroyed (today only around 50 per cent of the larger stones survive).

As a result of that partial demolition, the original acoustics were destroyed.

But now, scientists have succeeded in accurately recreating the monument’s original soundscape.

The new research – carried out by acoustics engineers from the University of Salford in Greater Manchester – has

revealed that the 20-40 tonne stones acted as a giant amplifier, which increased the decibel count of various sounds potentially produced in the monument’s inner sanctum by between 10 and 20 per cent (up to 10 decibels), compared to a more open environment.

However, the research also

demonstrated that any sounds produced inside the temple would have been much less audible to anybody outside the circle, despite the monument almost certainly not having a roof.

The findings therefore suggest that any sounds generated by activities carried out inside the circle were not intended to be shared with the wider community. This reinforces theories suggesting that the potential religious activities conducted inside Stonehenge were reserved for an elite of practitioners, rather than for a wider communal congregation.

Archaeologists don’t know whether the practices carried out inside Stonehenge involved any form of music or chanting or any other form of speech. But drums and wind instruments were used in western Europe, while Stonehenge was in use.

The findings from the new acoustic research suggests that deeper-sounding instruments like drums and lurs (giant ancient bronze horns) would have been particularly effective in producing strong reverberations and therefore greater amplification within the monument.

The Salford research has so far concentrated on how the acoustics of Stonehenge would have affected the human voice.

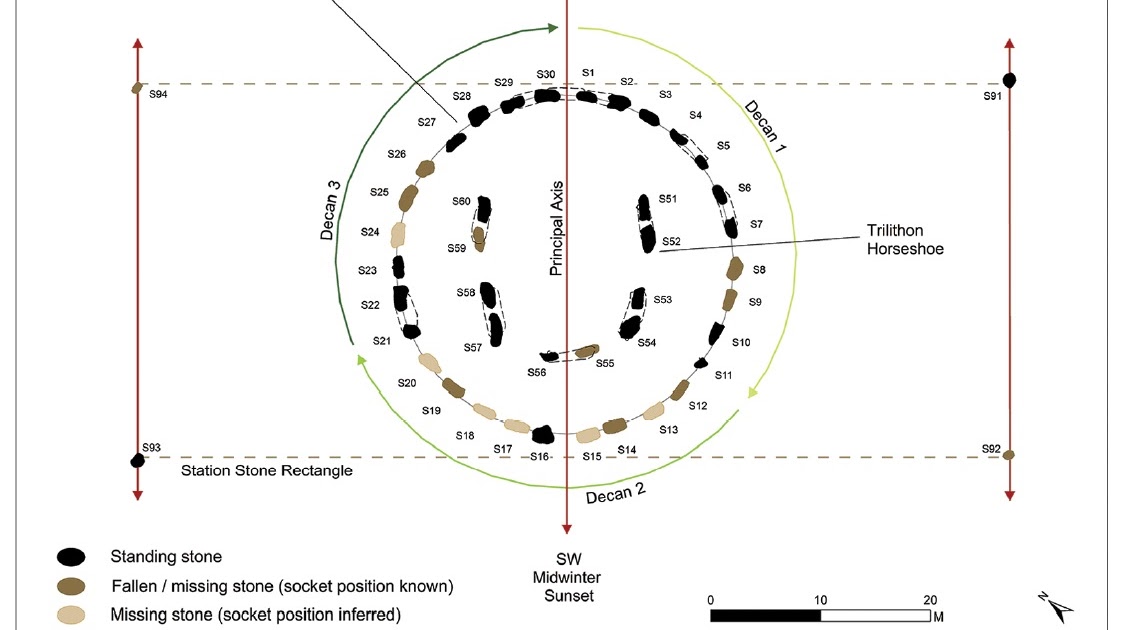

To recreate the ancient temple’s soundscape, scientists, led by Professor Trevor Cox, made a 1:12 scale model of what Stonehenge would originally have looked like before half its stones were removed.

That model – based on archaeological evidence – was then tested acoustically in Salford University’s sound laboratory, using the same acoustic testing techniques normally employed by sound engineers on scale-model prototypes of modern concert halls and opera houses.

Because the model Stonehenge was one-twelfth the size of the original, the sounds used in the test had to be twelve times normal frequency (ie extending into the ultrasonic range).

Salford University’s acoustic scale model of Stonehenge is 2.5m in diameter – and was 3D printed from a CAD (computer-aided design) software model supplied by Historic England which has archaeological responsibility for the monument. Using the CAD model, the scientists were even able to recreate the precise surface topography of each of the stones, thus ensuring a much more accurate replication of the original temple’s acoustic environment.

“Constructing and testing the model was very time consuming, a labour of love, but it has given the most accurate insight into the prehistoric acoustics to date. With so many stones missing or displaced, the modern acoustics of Stonehenge are very different to that in prehistory,” said Professor Cox.

The new acoustics research has been announced less than a month after archaeologists for the first time

identified the source of the prehistoric temple’s giant stones.