Betelgeuse faintest ever recorded, 'swollen' by 9%

Evan Gough, Universe Today

Phys.org

Thu, 23 Jan 2020 12:00 UTC

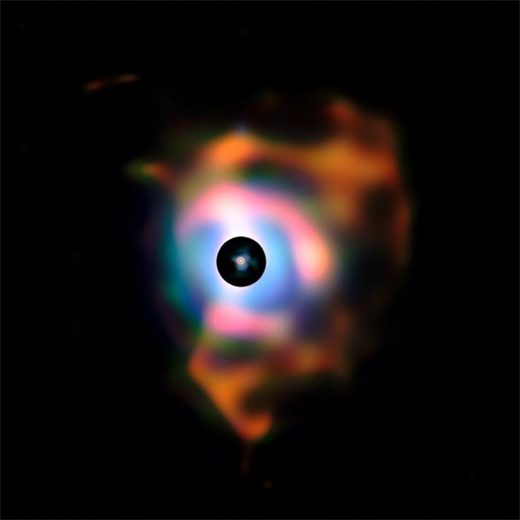

© ESO

This picture of the dramatic nebula around the bright red supergiant star Betelgeuse was created from images taken with the VISIR infrared camera on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT). This structure, resembling flames emanating from the star, forms because the behemoth is shedding its material into space. The small red circle in the middle has a diameter about four and half times that of the Earth’s orbit and represents the location of Betelgeuse’s visible surface. The black disc corresponds to a very bright part of the image that was masked to allow the fainter nebula to be seen.

Betelgeuse keeps getting dimmer, and everyone is wondering what exactly that means. The star will go supernova at the end of its life, but that's not projected to happen for tens of thousands of years or so. So what's causing the dimming?

Villanova University astronomers Edward Guinan and Richard Wasatonic were the first to report Betelgeuse's recent dimming. In a new post on

The Astronomer's Telegram, the pair of astronomers report a further dimming of Betelgeuse. They also point out that although the star is still dimming,

its rate of dimming is slowing.

Betelgeuse is a

red supergiant star in the constellation Orion. It left the main sequence about 1 million years ago, and has been a red supergiant for about 40,000 years. It's a core-collapse SN II progenitor, which means that eventually, Betelgeuse will burn enough of its hydrogen that its core will collapse and it will explode as a supernova.

It's known as a semi-regular variable star, which means its brightness is variable. One of its cycles is about 420 days long, and another is about five or six years. A third cycle is shorter; about 100 to 180 days. Though most of its fluctuations are predictable and follow these cycles, some of them are not, like the current dimming.

Astronomers have been monitoring Betelgeuse for a long time. Visual estimates of the star go back about 180 years, and since the 1920s, the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) have taken more systematic measurements. About 40 years ago, astronomers at Villanova University began taking systematic photometric measurements of Betelgeuse's brightness.

The photometry data from the last 25 years is the most thorough, and according to that data the star is as dim as it's ever been.

According to Guinan and Wasatonic's post on Astronomer's Telegram,

Betelgeuse's temperature has dropped by 100 Kelvin since September 2019, and its luminosity has dropped by nearly 25 percent in the same time frame. According to all of those measurements, the star's radius has grown by about 9 percent. This swelling is expected as Betelgeuse ages.

In a way, we're lucky to have Betelgeuse so close by, in astronomical terms, at least. It's only about 650

light years away, and that makes it a great teacher. It's the only star other than our sun on which we can see surface details. That helps astrophysicists understand what's happening there, and on other similar stars.

Like all stars, Betelgeuse generates heat in its core through fusion. The heat is transferred to its surface via convection. The currents that carry the heat are called convection cells, which can be seen on the surface as dark patches.

As the star rotates, these cells rotate in and out of view, which contributes to Betelgeuse's observed variability. Convection cells can be massive, even more so on the surface of a huge star like Betelgeuse.

In 2013, scientists reported evidence of convection cells on the sun that lasted for months. It wasn't conclusive, but could something like that be contributing to the dimming on Betelgeuse?

This dimming episode may not be the star itself, but rather a cloud of gas and dust obscuring the light. As time goes on, and Betelgeuse burns more of its fuel, it loses mass. As it loses mass, its gravitational hold on its outer edges is weakened, and clouds of gas escape the star into the surrounding regions. This could cause the current dimming episode.

Or could it be something else? We know a lot about

stars, but we don't know everything. We've also never been able to observe any other red super-giants the way we can with Betelgeuse.

© NASA

The familiar constellation of Orion. Orion’s Belt can be clearly seen, as well as Betelgeuse (red star in the upper left corner) and Rigel (bright blue star in the lower right corner)

Astronomers Know What'll Happen, They Just Don't Know When.

Whatever the cause, we know what the eventual end for Betelgeuse looks like: a supernova explosion. Whether this dimming is directly related to the approaching cataclysmic death of this unstable star is unknown at this point. As Guinan and Wasatonic say on Astronomer's Telegram, "The unusual behavior of Betelgeuse should be closely watched."

When Betelgeuse does eventually go supernova, it will be the most fascinating act of nature witnessed by any human ever. Other supernovae like SN 185 and SN 1604 were much further away than Betelgeuse.

When Betelgeuse goes supernova, it will the third-brightest object in the sky, after the sun and the full moon. But some estimates say it'll be even brighter than the moon.

Betelgeuse will light up the sky like no other supernovae, and

will last for months, visible in daytime, and casting shadows at night. Then, in about three years, it will fade to its current brightness. About six years after it goes supernova, Betelgeuse won't even be visible in the night sky. Orion the Hunter will be no more.

When, exactly, all this will happen, nobody knows. And though this recent dimming likely isn't directly connected to Betelgeuse's eventual supernova explosion, astronomers don't know that for sure, either.

) about the objects, perhaps Konstantin or someone else can make sense of it?

) about the objects, perhaps Konstantin or someone else can make sense of it?