Nunavik Inuit genetically unique among present-day world populations, study finds

Researchers mapped complete genetic profile of Inuit in Nunavik region for 1st time

Priscilla Hwang · CBC News · Posted: Jul 23, 2019 3:00 AM CT | Last Updated: July 23

A file photo of the northern village of Kangiqsualujjuaq, Que. Some community members participated in a new study published Monday about the genetic architecture of Inuit in the Nunavik region. (Catou MacKinnon/CBC)

Researchers have found that Inuit from northern Quebec are genetically distinct from any present-day population in the world, and say studying the genes of minority Indigenous populations in Canada can help deliver better health care to these populations.

In a

study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers mapped the complete genetic profile of Inuit in the Nunavik region — what they claim is a first. Researchers then homed in to study the effects these genetic variants may have on disorders like brain aneurysms.

"That's the novelty of this study," said Sirui Zhou, the primary author of the study and a researcher with the Neuro (Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital).

Zhou said only a small group of Arctic Inuit have been genetically profiled around the world, as with most Indigenous populations in Canada.

"There's a lot to learn from genomes of smaller populations that are understudied," said Patrick Dion, assistant professor at McGill University, one of the study's authors.

We're hoping that this study can inspire … a lot more genetic studies on Inuit, Aboriginal people.- Sirui Zhou, primary author of study

Researchers compared the genetic profile of 170 Nunavik Inuit with "everyone possible" from Asians, Africans, and Europeans to North and South Americans.

"They were very different, as was expected," said Zhou.

Then researchers compared the profile with those available from other Indigenous populations, from Greenlandic Inuit to Indigenous groups from North and South America, Alaska, and Siberia.

"[Nunavik Inuit] were still … unique, because they are isolated, homogenous, and not known to have admixed with other populations," said Zhou.

"They do not share similar genetic components [or] genetic structure to any kind of present-day, worldwide populations."

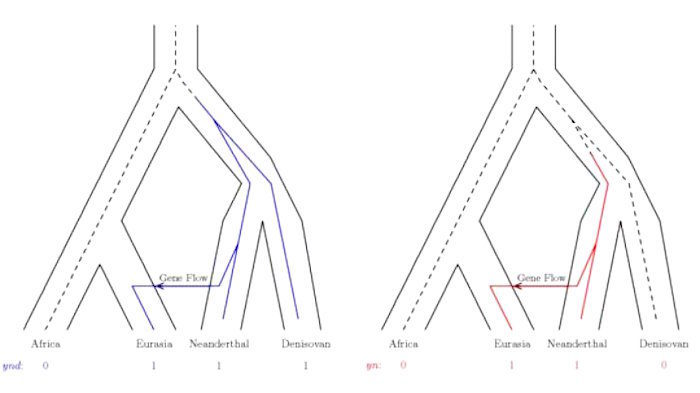

(Below is a relationship tree diagram showing Nunavik Inuit (bottom corner) with other Indigenous populations. Credit: The Neuro)

The study found Nunavik Inuit may have genetic components derived from ancient Arctic Indigenous populations.

"Paleo-Eskimo [genetic] ancestry is almost extinct in all current populations. But Nunavik Inuit probably have the largest component of an ancestry that could be likely derived from [the] Paleo-Eskimo

."

Zhou said while looking at the exonic regions of the Nunavik Inuit's genome — "the most important regions" which are responsible for coding proteins — she found about 130 unique genetic variations.

Zhou said to her knowledge, that seems to be "a substantial amount."

Over the course of 25 years, 170 participants were recruited to participate in the study, mainly after physicians referred them to go to Montreal for screenings for brain aneurysms. Some participants were family members of people at risk for the disorder, who were getting proactive screening; others were partners who were married into the family, who wouldn't necessarily have that risk, Zhou said.

There are 14 communities scattered across the Nunavik region of Quebec, by Hudson Bay and Ungava Bay.(Kativik School Board)

Participants were from across the Nunavik region from both the Hudson Bay and Ungava Bay area. Ten communities were represented, and many from Ivujivik and Kangiqsualujjuaq, said Zhou.

Zhou said the 170 sample size is a fair representation of the population, at approximately one per cent of Nunavik's population according to the 2016 census.

Higher risk for brain aneurysm

The study also found a unique genetic variant in Nunavik Inuit that is associated with a higher risk to develop brain aneurysms.

It's too early to have practical results with this research. But it's opened the door to go a little bit further.- Marie Rochette, Nunavik director of public health

Zhou said researchers have two hypothesis as to why Nunavik Inuit are at higher risk for this disorder: firstly, because of the small population size, some genetic variants that cause diseases "happen to accumulate in high frequency," increasing the risks. Secondly, Zhou said those same variants may have historically had other beneficial functions for Inuit, like their ability to adapt to harsher environments.

Zhou noted that multiple genetic variants and environmental factors are involved in contributing to developing a brain aneurysm.

Sirui Zhou, left, and Patrick Dion, right, are two of the study's authors. (The Neuro)

Zhou said knowing the genetic makeup of Indigenous groups could provide better health care for those populations — like helping communities screen people for diseases they're at higher risk for genetically.

"We're hoping that this study can inspire … a lot more genetic studies on Inuit, Aboriginal people," said Zhou. "So we can actually design health care to suit them better."

Genetics only 'part of equation'

"It's very promising knowing that there's a specific gene that seems to be related to cerebral aneurysm," said Marie Rochette, director of public health for Nunavik Regional Board of Health and Social Services.

"On the other side, we have to think about genetics as one part of the equation," said Rochette, who wasn't involved in the research.

"We have to be cautious. It's not because you have a specific genetic thread that means you will develop a disease. There are many other risk factors associated."

Factors such as diet, substance use habits and living conditions can influence the pattern of the disease, she said.

Rochette said the study won't have a direct effect on the 14 communities. She said more research needs to be done.

"It's too early to have practical results with this research. But it's opened the door to go a little bit further."

Rochette added that Inuit are more and more involved in research, and they not only want to be subjects of research, but also be part of how the results are interpreted and used.