You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

THE ONCE AND FUTURE SKY GOD? – From Göbekli Tepe to The Zodiac – and Beyond…

- Thread starter Michael B-C

- Start date

There is a series of videos from the See the Pattern channel on youtube that aggregates several of these concepts that Sweatman seems to ignore.

Well Bluegazer you've beaten me to the draw! I will be coming to the crucial matters raised by See the Pattern in my next series of posts. And its going to be another big one I'm afraid to get there in one arch from where we are now! Hold tight!

Started watching these @Bluegazer - only onto the 4th in the series, and see the Pleiades factors significantly alongside Birkeland currents (discussed with Jim Weninger in part III). I don't know what to think regarding gravity (looked at the experiment in space with the gyroscope - so get that) mixed into the electrical, and here Ark receives answers to ponder. This seems to be where the C's amalgamate the two properties.

(Ark) My question is that in my research, related to the paper I've been writing for a year now, there appears a mathematical structure, an antisymmetric matrix or something like that. I believe it's important, but I don't know whether it's related to action of electromagnetic field, or gravitational field, or some kind of informational field. I have no clue and I would like to have a hint what it is doing this thing that is there and I don't know what kind of job it is doing?

(L) So, you're asking if it's informational, gravitational, or electromagnetic?

(Ark) Or something else.

A: Electromagnetism structured by information emitted by gravity.

Q: (Ark) Alright. [laughs]

A: Go deeper to find the structuring forces.

Q: (Ark) Meow.

Gravity is not discussed with the Birkeland business, and in the series (thus far) they seem to dismiss gravity, don't know why, the electrical guys can't find applicable reason for it (the way the think it works). "Emitted by gravity" has to be in all this somewhere ("collected" as the C's said, and in a "perfectly balanced static state.") It seems the C's have described the electrical/gravity relationship i.e. when gravity reduces so does electrical influence (balance) and vice versa, and this might fit with the clockwork of the Birkeland plasma rope - upon the system/sun/planetary spiraling explanations. There is some kind of ebb and flow. Here in Session (March 2021) - although describing a particular, it seems to be describing the same matching balanced oscillations:

and:(Joe) So, gravity was less, let's say, to make it easy for them to...

A: Yes. Also electrical charge of planet.

Q: (L) You said that EM was the same as gravity. Does an increase in EM, the collection of EM or the production of an EM wave, does this increase gravity on those things or objects or persons subjected to it?

A: Gravity does not ever get increased or decreased, it is merely collected and dispersed.

Q: (L) If gravity is collected and dispersed, and planets and stars are windows, and you say that human beings "have" gravity, does that mean that the human beings, or the life forms on a given planet or in a given solar system, are the collectors of this gravity?

A: No. Gravity is the collector of human beings and all else! Make "collector" singular.

Regarding Birkeland, unless missed it, had only found it mentioned once in a 2017 Session:

Q: (Pierre) The last discussion was that there was a close encounter and a discharge because Mars and Earth have different electric potential. And there was this giant Birkeland current that not only carried electrons, but also water from Mars since water from Mars has the same electric potential as Mars.

A: Yes

Here is a capture of our system around the sun within the Gould Belt funnel (within the narrow gap), with Pleiades (and Arcturus) playing a central role, and the discussion on Sirius's (the explanation in the series equates it as a binary to our sun, which contradicts what the C's have said of our binary star, osi-remember) regular heliacal rising on earths horizon, and why others don't, by degree following in time.

I would hope that Orion would be familiar to most of us here. It is arguably the most readily identifiable constellation in the entire night sky – the ‘hunter’ as it is also still known to many. But Arcturus?

Yes, see Arcturus and its positioning now from the series watched, and it is enough to make one feel pretty small.

What happened in the past, with where you might be leading Michael B-C, with the H et cetera (hinted at in the series in the plasma current and shown in your depictions and analysis), it must have been incredibly profound in the eyes and minds of earths terra firma denizens. Some kind of massive window opening up that would impact for a long time to come and featured in the language, a math and art of the days.

And now to the strangest of things... according to uniformitarian retrograde calculations, the Pleiades were last seen rising heliacally in a November all of twelve thousand years ago. Bang in line with the time period of our terrible end to the Younger Dryas and also within a reasonable proximity to the possible ‘commemoration’(?) marked by our T-pillar 18 at Göbekli Tepe with those seven birds waddling by….

Yes, see what you are saying, and in the series there is mention of the timepiece-gear calculating the periods in very small cycling increments out to 26,000 years, and longer in some calendars.

THE TZOLK'IN - The Cycle of the Pleiadies

The Tzolk'in is a two geared spiracle watch. It is based on the cycles of the Pleiadies (26,000 years) but is used in factual form with 260 days. The mathematics used in the Tzolk’in are 13 times 20, 13 numbers and 20 glyphs. A interesting note here is it takes Earth 26,000 years to circumnavigate the Zodiac!

The Numbers/Pulses (1-13) of the Tzolk'in are the ”movement” of the sacred calendar. The number 13 represents the spirit, the holy breath of creation. The numbers pulse in an undulating cycle of creation. Each sacred number holds a position, or intention, in the creation process and pulses creative energy in an ascending spiral. When your reach point #13 you jump up a rung of the evolutionary ladder. The Mayas used a bar-dot number system. One dot = one, One Bar = 5.

The Glyphs/Suns (1-20) of the Tzolk'in are the “measure” of the sacred calendar. They are the 20 Sun glyphs that are familiar to anyone who has been interested in the Mayan calendar. They represent the body of creation. They define, or create definition. Each Mayan Sun name, has a corresponding glyph and cycles in a regular ascending order of definition which is encoded with cosmic evolutionary information. Just as the numbers ascend from one cycle to the next, so do the 20 suns. When the 20 Suns mesh with the 13 numbers there are 260 combinations of creation. (see Sun glyph chart)

Will hold tight as you continue (as Lennon said “the more I see, the less I know for sure.”), and thank you thus far. Perhaps some good C's questions that can't be discovered may also come up.

If Orion was the central hub according to the C's, and civilizations of the past had a direct connection (seen in archology and some texts to the point that it can be hypothesized), the "deliberate" nature to cut us off from our connected created birthright seems to have been at play for thousands of years. Organizations like UNESCO controlling digs and narratives, do their part, as do old text translations.

The myth and story of orion and the Pleiades feels like the record of a geopolitical (well, more like cosmic in this case) event. Where you have the STS half of the region expanding and conquering and the STO half defending itself. All of this occurring in the entire sector of the galaxy described by the C's. I think our ancestors knew more about this cosmic geopolitics, much more than we know today.

Gravity is not discussed with the Birkeland business, and in the series (thus far) they seem to dismiss gravity, don't know why, the electrical guys can't find applicable reason for it (the way the think it works). "Emitted by gravity" has to be in all this somewhere ("collected" as the C's said, and in a "perfectly balanced static state.") It seems the C's have described the electrical/gravity relationship i.e. when gravity reduces so does electrical influence (balance) and vice versa, and this might fit with the clockwork of the Birkeland plasma rope - upon the system/sun/planetary spiraling explanations. There is some kind of ebb and flow. Here in Session (March 2021) - although describing a particular, it seems to be describing the same matching balanced oscillations:

Q: (L) You said that EM was the same as gravity. Does an increase in EM, the collection of EM or the production of an EM wave, does this increase gravity on those things or objects or persons subjected to it?

A: Gravity does not ever get increased or decreased, it is merely collected and dispersed.

Q: (L) If gravity is collected and dispersed, and planets and stars are windows, and you say that human beings "have" gravity, does that mean that the human beings, or the life forms on a given planet or in a given solar system, are the collectors of this gravity?

A: No. Gravity is the collector of human beings and all else! Make "collector" singular.

Reading this part of your post, I was reminded of the 19 year metonic cycle:

19 Year Cycle Lunar Standstill Upcoming

Back when Secret History was going through its first edits, Frank J (QFG researcher) was quite fascinated by the discussion of the 19 year cycle. He decided to do some research. The graphs and things he included in his paper aren't included in the following, but they aren't necessary. What...

Back when Secret History was going through its first edits, Frank J (QFG

researcher) was quite fascinated by the discussion of the 19 year cycle.

He decided to do some research.

The graphs and things he included in his paper aren't included in the following, but they aren't necessary. What is important are his remarks as well as the upcoming event.

Those who have read "The Secret History of the World" are aware of the possible significance of this event.

19-year Lunar Cycles

By Frank J

I was inspired to put together this little paper by the discussion in

'Secret History' concerning the importance of the 19-year lunar cycle in the

cultures of some ancient civilizations, in particular the culture that

flourished around Stonehenge. The C's suggests that the 19-year cycle is a

window, gravitationally induced, for direct access by humans ("right

people, right place, right activity, right time") can directly access

higher dimensions without any help from other entities. by engaging in group activities,

carried out in a geometric pattern, and with certain amplification materials in particular geographic locations,

and the participants having fused their magnetic centers,

And, of course, I am also interested in where we are now in that cycle.

A bold theory: What if much of the ancient knowledge, cosmic geopolitics corresponded by far to knowing the cycle of gravitational dispersion and collection that allowed the passage or crossing between densities, as even other dimensions! That is, the whole matter of the Pleiades, Arcturus, our solar system, our ancestors knew the exact moment in the cycles where by the action of the electrogravitational interaction of the interconnected system of birkeland currents, the windows were opened.

There would be smaller cycles where the window is limited, and large transition cycles where the window opening is much longer, sustained and stable.

If I remember correctly, the C's had commented that a great cycle was about to end (or begin?). The wave is the primary component of this cycle. Did our pre-fall ancestors know about the periodicity of the wave?

Wandering Star

The Living Force

Xpan just wrote this post and...More rings, swirls and strange lights

20 June 2022 • Spaceweather.com

An interesting article was published at spaceweather.com today on 20 June 2022, about phenomenas revolving around SpaceX / Falcon9 rocket.

Following was written:

STRANGE THINGS IN THE SKY, COURTESY OF SPACEX

On Sunday morning, June 19th, SpaceX launched a Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral (0427 UT). Within hours, people around the world started seeing strange things in the sky. First there was a "smoke ring." Jerrod Wood video-recorded it from central Illinois:

"I believe it shows the the orbital insertion of the Globalstar FM15 satellite as it separated from the Falcon 9's upper stage," says Wood.

He's right. Almost two hours after launch, the upper stage of the Falcon 9 deployed the Globalstar communications satellite; the smoke ring Wood saw was the "puff" of separation. Because it happened so far above Earth, more than 700 miles high, people saw the event across much of North America from Arizona to Missouri and beyond.

An hour after the smoke ring, things got really strange. People in New Zealand saw this:

View attachment 59804

"It looked like a beautiful galaxy appeared in the sky," says Alasdair Burns of Twinkle Dark Sky Tours. "It was a very slowly rotating spiral that started small and gradually expanded. Eventually it became so large and faint that it could no longer be seen. There were a group of us on our balcony watching it and none of us had ever seen anything like it."

This spiral was almost certainly the tumbling upper stage of the Falcon 9 rocket executing a fuel dump. Similar spirals have been seen after previous Falcon 9 launches. This is an exceptionally clear photo of the phenomenon.

Finally, David Cortner of Rutherford College, North Carolina, saw something truly puzzling. He calls it "rocket powered aurora." This 8-frame mosaic shows a red band that appeared shortly after the launch:

View attachment 59805

"I went out to watch the midnight launch of the Falcon 9," says Cortner. "Here in western North Carolina, I was hoping for a faint, moonlit 'jellyfish.' The rocket's trajectory was much higher than I expected, however; it was almost 500 km high by the time it was due east of me, not 150-200 km as are most SpaceX flights up the Atlantic coast. As a result the rocket passed by me unseen."

"A minute or two after the rocket's closest approach (by the clock), I noticed this red glow spreading across a broad swath of the eastern sky." There was no space weather event in progress. Cortner speculates that the rocket itself somehow stimulated oxygen atoms ~500 km high to produce an artificial aurora. For reference, natural red auroras range in altitude typically from 150 km to 250 km, and more rarely all the way up to 600 km.

We do not know what produced this glow. Readers with good ideas are encouraged to share them

END OF ARTICLE

There is an H next to the spiral with And a crescent on the spiral

Attachments

Last edited:

Wandering Star

The Living Force

Did our pre-fall ancestors know about the periodicity of the wave?

Some periods of post-fall certainly seemed to know a great deal about periodicity (language of a wave, don't know). So, the likelihood is good, or perhaps better for pre-fall, too.

In one of Michael B-C's photos (see below), it also came up in one of the video series you provided - Arcturus the Star of Joy section. Thus, they were talking about Arcturus (Red Giant) tracking across the biblical dates of the grand birth - but in the spring/summer months.

Protogeneia- the first born ?

Physis was a primeval god or goddess of the origin and ordering of nature. The primal being of creation was regarded as both male and female. See Physis (or Phusis).

“O Natura [Phusis, nature], mighty mother of the gods [Gaia (see above) is probably meant], and thou, fire-bearing Olympus’ lord [Zeus] … why dost thou dwell afar, all too indifferent to men, not anxious to bring blessing to the good, and to the evil, bane?” [Seneca, Phaedra 959]

“Then Phusis (Nature), who governs the universe and recreates its substance [after the world-shattering battle between Zeus and Typhoeus], closed up the gaping rents in earth’s broken surface, and sealed once more with the bond of indivisible joinery those island cliffs which had been rent from their bed.” [Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2. 650 ff (trans. Rouse) (Greek epic C5th A.D.) PHYSIS - Greek Primordial Goddess of Nature (Roman Natura)

Physis was a primeval god or goddess of the origin and ordering of nature. The primal being of creation was regarded as both male and female. See Physis (or Phusis).

“O Natura [Phusis, nature], mighty mother of the gods [Gaia (see above) is probably meant], and thou, fire-bearing Olympus’ lord [Zeus] … why dost thou dwell afar, all too indifferent to men, not anxious to bring blessing to the good, and to the evil, bane?” [Seneca, Phaedra 959]

“Then Phusis (Nature), who governs the universe and recreates its substance [after the world-shattering battle between Zeus and Typhoeus], closed up the gaping rents in earth’s broken surface, and sealed once more with the bond of indivisible joinery those island cliffs which had been rent from their bed.” [Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2. 650 ff (trans. Rouse) (Greek epic C5th A.D.) PHYSIS - Greek Primordial Goddess of Nature (Roman Natura)

Michael B-C

The Living Force

TAURUS THE BULL

Having for long now focused in on the Pleiades, it is time for us to take a step back so we can enjoy a broader view of the great constellation of Taurus in which the Pleiades sits.

I have already proposed elsewhere that Taurus is actually a housing for a far distant memory of THE GREAT BULL OF HEAVEN, that I am proposing was once a quite different phenomenon dominating the northern sky, which along with a host of other vanished primal aspects from prehistoric times, was eventually transferred and translated (after these wonders departed our skies) onto a constellation that was to become a pivotal player in the zodiac of late antiquity.

The role of the bull (and hence of Taurus) in mythology - and indeed in civilisation and religion itself - is immense. It would take multiple volumes to document its centrality to Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Egyptian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Hebrew legends, to name but a few – and I haven’t even looked further east to say India or west to Mesoamerica with this geographic spread (or for example to Ireland where the twin bulls are central to the pivotal Irish mythological text Táin Bó Cúailnge – meaning the driving-off of the cows of Colley - in which indigenous aspects comparable to the Troy mythos comes to the fore as late as the 6th century AD). Who after all hasn’t heard of the golden bull calf of the Old Testament, or of the Minotaur snorting and roaring from within the darkened depths of the Labyrinth on Crete, or that the great Greek god Zeus himself rode across the crest of a wave upon the back of white bull when he kidnapped Europa, or that a horned bovine attended the birth of Jesus in the manger at Bethlehem? And always nearby, yet still central to these stories, is the virgin princess. Osiris, the principle god of Egypt, (husband of Isis), was originally also a bull – as were so many, many other gods of the ancient world. The last outpouring of ancient memory saw Mithras slay the bull whilst a zodiac swirled all about them and who doesn’t know something of Spanish bull fighting where even to this day the hero pits his speed and guile against the ferocious power and blood pumping rage of a charging bull, its horns lowered for the kill? Not to mention our moon as a bull’s horns carved so evocatively in the sky or the fact that startling, lifelike representations of auroch bulls adorned the Palaeolithic caves of France (and are those the Pleiades above the shoulder of the Lascaux bull all those long, long millennia ago...?).

Indeed, it is once again time to apply that repeatedly utilised word of mine – reverence for the bull was indeed ubiquitous.

The ancient Greeks held to a philosophical concept known as Zoe and Bios. Zoe was an eternal string of pearls that was all of life itself in its perpetual state of eternal being and becoming. Bios was its singular offspring, its perpetual child, a single glistening pearl that repeatedly falls to earth and manifests the entire information field of the creative whole in the guise of a singular, material force of nature – and that child (man/god) was a bull calf. The micro in the macro, the macro in the micro. Thus, for the ancients, the pulsatingly charged bull was the very definition of divine life itself made manifest, and it was religion.

It should appear anomalous therefore, that this magnificent symbolic creature appears only in an abbreviated form in the zodiac. Unlike say the ram of Aries or the lion of Leo, Taurus the bull is brutally truncated, with its entire hind and back legs missing and only the front half of the bull making up the body of the constellation (I will come back to this profound mystery anon).

Let’s first head over to Wikipedia for a brief but actually revealing overview of the constellation from an astronomical perspective:

Yes, indeed - most revealing…

As you can see in the above, historically the constellation has long been viewed as having at least three distinct units. Besides the Pleiades and the bull itself, there are also the Hyades which we will touch upon shortly. But it is to the Great Bull of Heaven that we turn first for further clues.

This is possibly the hardest section I have yet composed simply because there is so much information it is tough to know what to leave in our out so as to keep the matter succinct enough to digest. Therefore, I am going to skip all the famous Greek tales for now and go back to Mesopotamia and straight to the bull’s mouth so to speak – because that’s where our story springs to life via some of the earliest texts and images on the matter. It is also the closet geographically to our reference point of Göbekli Tepe.

THE GREAT BULL OF HEAVEN (PART 1)

Cattle are thought to have been first domesticated in the fertile valleys of Mesopotamia round about 7000 BCE but the wild auroch, which had roamed the plains since time immemorial, was a more massive creature than your docile cow, standing over six feet tall. With near supernatural strength and ferocity, it was likened to gods, kings and heroes. Its broad curving horns played an exoteric role in inspiring the horned headdress that all gods and goddesses wore to signify their divine status (but as we have been exploring, this signature of royalty and deity has even deeper cosmological roots).

The overriding motive for their domestication was not for their meat but for their great strength, which was harnessed by early farmers to provide traction for ploughs and threshing sledges. Most households would only keep one or two beasts, with large herds being much rarer and only being kept by the palace and temple, whose financial and logistic resources were capable of supporting them. Milk, their most valuable by-product, was turned into cheese, butter and ghee.

In the artwork of the 4th and 5th millennium the bull is first combined with an ear of barley. For most mainstream scolastic interpreters today, together these symbolise the wealth and bounty of the renewable land brought about by the Neolithic farming revolution, but I believe this is not what is being principally honoured here (though as we will cover later the undeniable reality that the grimreaper of harvest time also clears the way and brings with it renewal and the potential for new growth, and so I do think this idea is imperative to always keep in mind as we go forward).

An impression from an early Sumerian cylinder seal

A cylinder seal from Uruk/Jemdet Nasr, Circa 3000 B.C.

In the above cylinder seal from Uruk (see more about this culture below), the same idea as with the stalk of barley in the previous seal is being conveyed here by the 'tree'. If we take a closer look at the ear of the barley from the first seal....

Note how the barley/tree (electrical phenomena) goes through the neck region of the bull in both images despite being perhaps up to 1,000 or more years apart. A further 3,000 years later, this is the very place that Mithras will strike, as the zodiac rolls on by.

Also note how in the first image the barley head with its 7 seeds is highly suggestive of a comet cluster. In the same vein note that there are 7 off shoots to the ‘tree’ in the other seal image. Yes, we are likely talking the Pleiades again here… and also likely the Hyades - but is this all they represent? I somehow doubt it. If you look at the picture below of astronomical relationships it suggests that the path to/from Pleiades-to Hyades symbolically mirrors the line of the barley/’comet cluster’ through the bull’s neck.

Very similar ideas about celestial cattle can be found in early mythology the world over. The Egyptian goddess Hathor, (along with Sekhmet, a manifestation as the eye of Ra – that is Chronos, not originally our sun as is repeated ad infinitum today - in her leonine ‘female’ aspect of the divine Chronos configuration), was often also envisioned as a star-spangled cow with a disk set between her horns. However, in very early pre-dynastic images she was often represented as follows:

Hathor the Celestial Heavenly Cow - Egyptian Predynastic

Those following my argument to date will have learned by now how to interpret this complex of interconnected symbols in one.

Comparable ideas can also be found in Vedic literature where herds of cows represent the fertile rains of the heavens (remember the Pleiades and the deluge?) By much later times, long after the knowledge behind its original form had been lost, the golden calf came to represent the new-born sun of spring emerging from the cosmic waters just as the new-born calf emerges from the life-giving waters of the womb.

The role of the bull as a symbol of prosperity and abundant herds is conveyed in a pair of later, contrasting Babylonian omens:

But if its stars are very faint:

These omens expose part of the most straightforward encoding level of the scheme that underpins celestial divination - if a star or constellation is ‘bright’ its meaning is positive, but if it is ‘faint’ or ‘obscured’ the prediction is negative. I believe the Babylonians also knew full well that cattle = the human herd as well.

Beyond their nature as symbols of the land’s prosperity, the bull, cow and calf all have a decidedly celestial quality to their character. Sumerian poetry sometimes refers to rain-laden clouds (here once more are the Pleiades and the deluge?) as the ‘bull-calves of the storm god’ and other texts attribute huge herds of cattle to the moon god Sin (again originally a deity with a quite different meaning once more later transferred onto our moon), their numbers - well over half a million individual beasts - are so implausibly large that the prosaic suggestion by scholars that this represents the stars of the sky is clearly ridiculous with the more likely hint here of a time remembered of a bombardment by the antecedent source or more active later form of the Taurid meteor stream.

"...the pillar of stars...the Bull of Heaven... whose horn shine, the well anointed pillar, the Bull of Heaven".Egyptian pyramid texts, relating to the mythic bull Kenset

"Shining Horn, the Pillar of Amentet".The 'Litany of Ra' - Egyptian text

Having for long now focused in on the Pleiades, it is time for us to take a step back so we can enjoy a broader view of the great constellation of Taurus in which the Pleiades sits.

I have already proposed elsewhere that Taurus is actually a housing for a far distant memory of THE GREAT BULL OF HEAVEN, that I am proposing was once a quite different phenomenon dominating the northern sky, which along with a host of other vanished primal aspects from prehistoric times, was eventually transferred and translated (after these wonders departed our skies) onto a constellation that was to become a pivotal player in the zodiac of late antiquity.

The role of the bull (and hence of Taurus) in mythology - and indeed in civilisation and religion itself - is immense. It would take multiple volumes to document its centrality to Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Egyptian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Hebrew legends, to name but a few – and I haven’t even looked further east to say India or west to Mesoamerica with this geographic spread (or for example to Ireland where the twin bulls are central to the pivotal Irish mythological text Táin Bó Cúailnge – meaning the driving-off of the cows of Colley - in which indigenous aspects comparable to the Troy mythos comes to the fore as late as the 6th century AD). Who after all hasn’t heard of the golden bull calf of the Old Testament, or of the Minotaur snorting and roaring from within the darkened depths of the Labyrinth on Crete, or that the great Greek god Zeus himself rode across the crest of a wave upon the back of white bull when he kidnapped Europa, or that a horned bovine attended the birth of Jesus in the manger at Bethlehem? And always nearby, yet still central to these stories, is the virgin princess. Osiris, the principle god of Egypt, (husband of Isis), was originally also a bull – as were so many, many other gods of the ancient world. The last outpouring of ancient memory saw Mithras slay the bull whilst a zodiac swirled all about them and who doesn’t know something of Spanish bull fighting where even to this day the hero pits his speed and guile against the ferocious power and blood pumping rage of a charging bull, its horns lowered for the kill? Not to mention our moon as a bull’s horns carved so evocatively in the sky or the fact that startling, lifelike representations of auroch bulls adorned the Palaeolithic caves of France (and are those the Pleiades above the shoulder of the Lascaux bull all those long, long millennia ago...?).

Indeed, it is once again time to apply that repeatedly utilised word of mine – reverence for the bull was indeed ubiquitous.

The ancient Greeks held to a philosophical concept known as Zoe and Bios. Zoe was an eternal string of pearls that was all of life itself in its perpetual state of eternal being and becoming. Bios was its singular offspring, its perpetual child, a single glistening pearl that repeatedly falls to earth and manifests the entire information field of the creative whole in the guise of a singular, material force of nature – and that child (man/god) was a bull calf. The micro in the macro, the macro in the micro. Thus, for the ancients, the pulsatingly charged bull was the very definition of divine life itself made manifest, and it was religion.

It should appear anomalous therefore, that this magnificent symbolic creature appears only in an abbreviated form in the zodiac. Unlike say the ram of Aries or the lion of Leo, Taurus the bull is brutally truncated, with its entire hind and back legs missing and only the front half of the bull making up the body of the constellation (I will come back to this profound mystery anon).

Let’s first head over to Wikipedia for a brief but actually revealing overview of the constellation from an astronomical perspective:

Taurus (Latin for "the Bull")… is a large and prominent constellation in the Northern Hemisphere's winter sky between Aries to the west and Gemini to the east; to the north lies Perseus and Auriga, to the southeast Orion, to the south Eridanus, and to the southwest Cetus... It is one of the oldest constellations, dating back to the Early Bronze Age at least, when it marked the location of the Sun during the spring equinox. ... A number of features exist that are of interest to astronomers. Taurus hosts two of the nearest open clusters to Earth, the Pleiades and the Hyades, both of which are visible to the naked eye. At first magnitude, the red giant Aldebaran is the brightest star in the constellation. In the northeast part of Taurus is the supernova remnant Messier 1, more commonly known as the Crab Nebula. One of the closest regions of active star formation, the Taurus-Auriga complex, crosses into the northern part of the constellation…This constellation forms part of the zodiac and hence is intersected by the ecliptic. This circle across the celestial sphere forms the apparent path of the Sun as the Earth completes its annual orbit. As the orbital plane of the Moon and the planets lie near the ecliptic, they can usually be found in the constellation Taurus during some part of each year. The galactic plane of the Milky Way intersects the northeast corner of the constellation and the galactic anticenter is located near the border between Taurus and Auriga. Taurus is the only constellation crossed by all three of the galactic equator, celestial equator, and ecliptic. A ring-like galactic structure known as Gould's Belt passes through the constellation. …During November, the Taurid meteor shower appears to radiate from the general direction of this constellation. The Beta Taurid meteor shower occurs during the months of June and July in the daytime, and is normally observed using radio techniques. Between 18 and 29 October, both the Northern Taurids and the Southern Taurids are active; though the latter stream is stronger. However, between November 1 and 10, the two streams equalize.

A number of features exist that are of interest to astronomers. Taurus hosts two of the nearest open clusters to Earth, the Pleiades and the Hyades, both of which are visible to the naked eye. At first magnitude, the red giant Aldebaran is the brightest star in the constellation. In the northeast part of Taurus is the supernova remnant Messier 1, more commonly known as the Crab Nebula. One of the closest regions of active star formation, the Taurus-Auriga complex, crosses into the northern part of the constellation…This constellation forms part of the zodiac and hence is intersected by the ecliptic. This circle across the celestial sphere forms the apparent path of the Sun as the Earth completes its annual orbit. As the orbital plane of the Moon and the planets lie near the ecliptic, they can usually be found in the constellation Taurus during some part of each year. The galactic plane of the Milky Way intersects the northeast corner of the constellation and the galactic anticenter is located near the border between Taurus and Auriga. Taurus is the only constellation crossed by all three of the galactic equator, celestial equator, and ecliptic. A ring-like galactic structure known as Gould's Belt passes through the constellation. …During November, the Taurid meteor shower appears to radiate from the general direction of this constellation. The Beta Taurid meteor shower occurs during the months of June and July in the daytime, and is normally observed using radio techniques. Between 18 and 29 October, both the Northern Taurids and the Southern Taurids are active; though the latter stream is stronger. However, between November 1 and 10, the two streams equalize.

Yes, indeed - most revealing…

As you can see in the above, historically the constellation has long been viewed as having at least three distinct units. Besides the Pleiades and the bull itself, there are also the Hyades which we will touch upon shortly. But it is to the Great Bull of Heaven that we turn first for further clues.

This is possibly the hardest section I have yet composed simply because there is so much information it is tough to know what to leave in our out so as to keep the matter succinct enough to digest. Therefore, I am going to skip all the famous Greek tales for now and go back to Mesopotamia and straight to the bull’s mouth so to speak – because that’s where our story springs to life via some of the earliest texts and images on the matter. It is also the closet geographically to our reference point of Göbekli Tepe.

THE GREAT BULL OF HEAVEN (PART 1)

Cattle are thought to have been first domesticated in the fertile valleys of Mesopotamia round about 7000 BCE but the wild auroch, which had roamed the plains since time immemorial, was a more massive creature than your docile cow, standing over six feet tall. With near supernatural strength and ferocity, it was likened to gods, kings and heroes. Its broad curving horns played an exoteric role in inspiring the horned headdress that all gods and goddesses wore to signify their divine status (but as we have been exploring, this signature of royalty and deity has even deeper cosmological roots).

The overriding motive for their domestication was not for their meat but for their great strength, which was harnessed by early farmers to provide traction for ploughs and threshing sledges. Most households would only keep one or two beasts, with large herds being much rarer and only being kept by the palace and temple, whose financial and logistic resources were capable of supporting them. Milk, their most valuable by-product, was turned into cheese, butter and ghee.

In the artwork of the 4th and 5th millennium the bull is first combined with an ear of barley. For most mainstream scolastic interpreters today, together these symbolise the wealth and bounty of the renewable land brought about by the Neolithic farming revolution, but I believe this is not what is being principally honoured here (though as we will cover later the undeniable reality that the grimreaper of harvest time also clears the way and brings with it renewal and the potential for new growth, and so I do think this idea is imperative to always keep in mind as we go forward).

An impression from an early Sumerian cylinder seal

A cylinder seal from Uruk/Jemdet Nasr, Circa 3000 B.C.

In the above cylinder seal from Uruk (see more about this culture below), the same idea as with the stalk of barley in the previous seal is being conveyed here by the 'tree'. If we take a closer look at the ear of the barley from the first seal....

Note how the barley/tree (electrical phenomena) goes through the neck region of the bull in both images despite being perhaps up to 1,000 or more years apart. A further 3,000 years later, this is the very place that Mithras will strike, as the zodiac rolls on by.

Also note how in the first image the barley head with its 7 seeds is highly suggestive of a comet cluster. In the same vein note that there are 7 off shoots to the ‘tree’ in the other seal image. Yes, we are likely talking the Pleiades again here… and also likely the Hyades - but is this all they represent? I somehow doubt it. If you look at the picture below of astronomical relationships it suggests that the path to/from Pleiades-to Hyades symbolically mirrors the line of the barley/’comet cluster’ through the bull’s neck.

Very similar ideas about celestial cattle can be found in early mythology the world over. The Egyptian goddess Hathor, (along with Sekhmet, a manifestation as the eye of Ra – that is Chronos, not originally our sun as is repeated ad infinitum today - in her leonine ‘female’ aspect of the divine Chronos configuration), was often also envisioned as a star-spangled cow with a disk set between her horns. However, in very early pre-dynastic images she was often represented as follows:

Hathor the Celestial Heavenly Cow - Egyptian Predynastic

Those following my argument to date will have learned by now how to interpret this complex of interconnected symbols in one.

Comparable ideas can also be found in Vedic literature where herds of cows represent the fertile rains of the heavens (remember the Pleiades and the deluge?) By much later times, long after the knowledge behind its original form had been lost, the golden calf came to represent the new-born sun of spring emerging from the cosmic waters just as the new-born calf emerges from the life-giving waters of the womb.

The role of the bull as a symbol of prosperity and abundant herds is conveyed in a pair of later, contrasting Babylonian omens:

‘If the Bull of Heaven’s stars are very bright: the offspring of cattle will thrive’,

But if its stars are very faint:

‘the wealth of the land will disappear; the offspring of cattle and sheep will not thrive’.

These omens expose part of the most straightforward encoding level of the scheme that underpins celestial divination - if a star or constellation is ‘bright’ its meaning is positive, but if it is ‘faint’ or ‘obscured’ the prediction is negative. I believe the Babylonians also knew full well that cattle = the human herd as well.

Beyond their nature as symbols of the land’s prosperity, the bull, cow and calf all have a decidedly celestial quality to their character. Sumerian poetry sometimes refers to rain-laden clouds (here once more are the Pleiades and the deluge?) as the ‘bull-calves of the storm god’ and other texts attribute huge herds of cattle to the moon god Sin (again originally a deity with a quite different meaning once more later transferred onto our moon), their numbers - well over half a million individual beasts - are so implausibly large that the prosaic suggestion by scholars that this represents the stars of the sky is clearly ridiculous with the more likely hint here of a time remembered of a bombardment by the antecedent source or more active later form of the Taurid meteor stream.

Last edited:

Michael B-C

The Living Force

THE GREAT BULL OF HEAVEN (PART 2)

The Bull of Heaven was written as Mul Gu-An-na:

Let us here touch briefly upon the topic of cylinder seals.

This immense subject deserves a thread all of its own. I admit here to a personal passion for these astonishing, enigmatic, highly stylised and symbolic world’s in miniature, carved onto minute, expertly realised drums, (typically only about 1 inch or 2 to 3 cm high), before being rolled out on to fresh soft red clay to reveal their relief in full. I am frankly amazed how little regard these miracles of art are held in, for at their best they not only rival the finest of all craftsmanship, they also reveal in great detail a tale of a worldview and a knowledge system entirely at odds with accepted reality.

There are literally tens of thousands of them lying effectively idle in museums across the world, each with its own mysterious story to unfold.

From Wikipedia:

The skill and the technology involved is quite baffling because at the scale of detail realised, especially in the later works, (and considering they were supposedly worked using known tools), the results are seemingly impossible to reconcile.

As noted above by Wikipedia, the tablets are believed to be a precursor to - and indeed a form of - writing and therefore visual storytelling, and can effectively be read as script.

One of the many pivotal seals thus far unearthed dates from the Uruk period and which I will explore now – but first some background, again from Wikipedia, for those unfamiliar with Uruk, founded around 4,000BC:

Unfortunately, I cannot find an original image of the cylinder scroll ‘script’ I want to explore next (it’s in some file or other, but just when I want it, for the life of me…) so we will have to make do for now with an exact line drawing.

We don’t have a precise date for its creation but somewhere close to 3,500BC appears to be the thought:

On the right-hand side, the magnificent Bull of Heaven appears in profile with a series of three stars placed above its back, this being a variant form of the Mul-sign that signifies a ‘star, planet or constellation’. At the bulls front legs rests a large, enigmatic circular object mirroring the same smaller orb resting between its horns. ‘Floating’ before him, we have the sign for the imposing, implacable figure of the goddess Inanna (Venus), her status as a high deity marked by the singular eight-pointed star, with herself represented by the sacred ‘reed’ column that stands as tall as the bull. Above her signature star hovers twin symbolic images, one an inversion of the other, which together scholars claim represent her twin roles as the Morning and Evening star.

It is widely accepted that this seal not only furnishes us with the earliest evidence of a specific, known constellation in Mesopotamia (Taurus) but also represents the first definitive association of a planetary deity with a constellation.

I will make some further observations:

I will leave it for there for now – but I haven’t finished with Taurus yet, not by a long chalk. Therefore, I’ll pick up the further threads of Taurus (part 3) in my next post.

The Bull of Heaven was written as Mul Gu-An-na:

In Akkadian these signs are read together as alû - ‘the bull of heaven’, which occurs in mythic, magical and astrological texts.

The Gu-sign depicts the head of a bull. It only illustrates the most characteristic part of the bull as an abbreviation for the whole animal. Essentially the same symbol lives on in the form of the modern astrological sign for Taurus.

The Sumerian term Anna means ‘of heaven’. The An-sign, which depicts a star, has three distinct meanings - ‘heaven’, ‘god’ in general and the sky god ‘Anu’ in particular.

The final Na-sign functions as a grammatical element, here signifying the possessive case; so the whole name can be read either as the ‘Bull of Heaven’ or the ’Bull of Anu’ (Anu is another synonym for Chronos)

During the course of the 4th millennium the symbol of the bull began to be increasingly associated with a wide range of gods, and it is from this period that the very earliest direct evidence for the existence of any constellations can be found.

Let us here touch briefly upon the topic of cylinder seals.

This immense subject deserves a thread all of its own. I admit here to a personal passion for these astonishing, enigmatic, highly stylised and symbolic world’s in miniature, carved onto minute, expertly realised drums, (typically only about 1 inch or 2 to 3 cm high), before being rolled out on to fresh soft red clay to reveal their relief in full. I am frankly amazed how little regard these miracles of art are held in, for at their best they not only rival the finest of all craftsmanship, they also reveal in great detail a tale of a worldview and a knowledge system entirely at odds with accepted reality.

There are literally tens of thousands of them lying effectively idle in museums across the world, each with its own mysterious story to unfold.

From Wikipedia:

According to some sources, cylinder seals were invented around 3500 BC in the Near East, at the contemporary sites of Uruk in southern Mesopotamia and slightly later at Susa in south-western Iran during the Proto-Elamite period, and they follow the development of stamp seals in the Halaf culture or slightly earlier. They are linked to the invention of the latter's cuneiform writing on clay tablets. Other sources, however, date the earliest cylinder seals to a much earlier time, to the Late Neolithic period (7600-6000 BC), hundreds of years before the invention of writing.

The skill and the technology involved is quite baffling because at the scale of detail realised, especially in the later works, (and considering they were supposedly worked using known tools), the results are seemingly impossible to reconcile.

As noted above by Wikipedia, the tablets are believed to be a precursor to - and indeed a form of - writing and therefore visual storytelling, and can effectively be read as script.

One of the many pivotal seals thus far unearthed dates from the Uruk period and which I will explore now – but first some background, again from Wikipedia, for those unfamiliar with Uruk, founded around 4,000BC:

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates 30 km (19 mi) east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.Uruk is the type site for the Uruk period. Uruk played a leading role in the early urbanization of Sumer in the mid-4th millennium BC. By the final phase of the Uruk period around 3100 BC, the city may have had 40,000 residents, with 80,000-90,000 people living in its environs, making it the largest urban area in the world at the time. The legendary king Gilgamesh, according to the chronology presented in the Sumerian King List (henceforth SKL), ruled Uruk in the 27th century BC.According to the SKL, Uruk was founded by the king Enmerkar. Though the king-list mentions a king of Eanna before him, the epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta relates that Enmerkar constructed the House of Heaven for the goddess Inanna in the Eanna District of Uruk. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh builds the city wall around Uruk and is king of the city.

Unfortunately, I cannot find an original image of the cylinder scroll ‘script’ I want to explore next (it’s in some file or other, but just when I want it, for the life of me…) so we will have to make do for now with an exact line drawing.

We don’t have a precise date for its creation but somewhere close to 3,500BC appears to be the thought:

On the right-hand side, the magnificent Bull of Heaven appears in profile with a series of three stars placed above its back, this being a variant form of the Mul-sign that signifies a ‘star, planet or constellation’. At the bulls front legs rests a large, enigmatic circular object mirroring the same smaller orb resting between its horns. ‘Floating’ before him, we have the sign for the imposing, implacable figure of the goddess Inanna (Venus), her status as a high deity marked by the singular eight-pointed star, with herself represented by the sacred ‘reed’ column that stands as tall as the bull. Above her signature star hovers twin symbolic images, one an inversion of the other, which together scholars claim represent her twin roles as the Morning and Evening star.

It is widely accepted that this seal not only furnishes us with the earliest evidence of a specific, known constellation in Mesopotamia (Taurus) but also represents the first definitive association of a planetary deity with a constellation.

I will make some further observations:

- The script is likely singular in that all the elements go together to form one cohesive narrative, a single highly distinctive interconnected unit.

- The bull itself is the figure we have met from previous posts relating to the original phenomenon of The Great Bull of Heaven. This is witnessed by the orb or ‘star’ resting within the centre of its horns. Whether intentional or not – but I highly suspect it is – this in-profile image brings the persona even more fully to ‘life’ with the orb as the head and the left horn upraised like a curving arm. This ‘figure’ clearly grows out of the muscular being of the bull, its chest and forelegs forming the rest of the ‘pillar’ of the body - like the much later figure of a centaur…!

- This is where I wish I had the original to hand because the large orb at the bull’s feet is clearly very important but its shape may or may not be precisely depicted here. That being said, however, my instinct is that it may represent an egg. The egg from which all life symbolically emerges (in line with the ancient idea of the bull as symbol of the information field’s eternal creative capacity).

- The so called ‘sacred reed column’ of Inanna (Venus) is a well-documented motif and for millennia was used to denote her presence without further clarification required.

What is not well understood of course is that this image is of the goddess as a cosmic body (inner circular ‘head’) from out of which her long flowing hair emerges to form the whole of her ‘body’ in a complex plasma discharge tail. This flowing hair motif therefore signifies her cometary state, a memory that was to last down through the millennia even as far as to the Renaissance where Aphrodite is revealed by Botticelli emerging from her ‘sea’ shell with her red hair blowing wildly in the watery wind.

Inanna/Aphrodite/Venus’ glorious hair was both a symbol of her beauty and magnificence and also of her potential to bring about an state of universal terror – because one minute she could appear as the radiant queen of the sky but at the next turn into a raging Gorgon, her snake hair swirling into a violently discharging horror show as - with tongue extended - she filled the heavens with impending dread.We will no doubt return to the goddess of ‘love’ at a later stage, so I will leave this to rest for now. However, the big take away – apart from the clear depiction of her cometary nature that was fully known and understood at the time, (as witnessed by this landmark seal), is that the ‘bull’ phenomenon and the comet-goddess were intrinsically interlinked.

- Finally, what are we to make of this strange little pair of images?

This is said to depict the twin signs used to represent ‘sunrise’ and ‘sunset’ as an upright and then inverted image of the sun rising between a pair of twin peaks or mountains. As an attribute of Inanna, they identify her with the planet Venus, which is only seen as the Morning and Evening star. Well clearly I think this is nonsense as we have met this concept long before – at Göbekli Tepe on Pillar 18 and on the road up through time since then - together acting as a double symbol for the rotational capacity of the original ‘bull of heaven’. Seeing them both here on this seal is a further confirmation of this long adhered to memory (even if the original cause had been since forgotten or lost).

The idea that the bottom image of the two represents a sunset is laughable and only goes to show what confirmation bias does to your critical thinking skills (it reminds me of all those Egyptians who later worried about the Pharaoh falling out of his inverted boat!)

If we further remind ourselves, the mountain is also the bull's horns which is also a ship with the divine twins and their cradling arms, as witnessed by:

"Her starboard side is the right arm of Atum. Her larboard side is the left arm of Atum (Chronos)".Egyptian Coffin Texts.

Then we remember just how multi-layered, interconnected yet consistent the message is. Collectively all these elements do indeed provide a complex script – but one that at the earliest time of denoting the constellation of Taurus harks back to the original meaning of the Bull of Heaven now transferred to a sleepy seeming set of stars – but ones that still pack a hidden punch and in terms of their elements in disguise, lead us eventually to the possible secret behind the mystery of precession.

I will leave it for there for now – but I haven’t finished with Taurus yet, not by a long chalk. Therefore, I’ll pick up the further threads of Taurus (part 3) in my next post.

Last edited:

Michael B-C

The Living Force

THE GREAT BULL OF HEAVEN (PART 3)

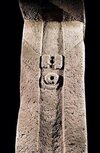

The idea of the great god being a sky-bull can be found on artifacts distributed throughout the Ancient Near East. On one such object, a square pedestal stone from Tayma in Saudi Arabia and dated to around 600-800 BCE, we find a most intriguing story.

Scholars assess that this Arabic artifact reveals how - many centuries on from the time we are exploring - both Egyptian and principally Babylonian influences made their way via Syria to Northern Arabia. There, three principle gods were absorbed: Salm, (namely our Chronos, but Anu to the Sumerians), Śangilā (the great on-its-back bull’s crescent aspect associated with the deity Sin); and Ášimā (Inanna namely Ishtar namely the comet Venus). This was the near universal sacred trinity of the time in Mesopotamia.

Present day interpretations by scholars of myths concerning this trinity make absolutely no sense, however – with them agreeing that the myths tell us that Sin (the Moon) was the father of Shamash (the Sun) and also of Ishtar/Inanna (Venus the planet). However, this was not always the case, as for example late 19th century scholar Peter Jensen in his ground-breaking study of Mesopotamian astronomy, Die Kosmologie der Babylonier, unequivocally identified the crescentine god Sin as the planet Saturn i.e. Chronos. Thus, if we think in terms of our story – that the Great Bull/Chronos (Sin) was the carrier/cradle for Shamash/Chronos (the orb) who spawned a daughter Venus (the comet), then we start getting somewhere. The stone from Tayma itself makes all this patently clear.

That this fascinating design is cubed is of immediate interest considering how Chronos/Saturn was the ‘cubed god’ (as witnessed by the sacred cubed Kaaba and its black meteorite stone at Mecca).

Of even greater note, all the usual suspects are again gathered together in one meaningful place, albeit at a much later date, and all etched in the traditional Babylonian style – the sacred head of the bull; the orb located in the crescent of its horns; the comet goddess Venus (shown both in her winged and magnificent – if menacing - state when in close proximity to earth and also as an eight pointed star – her more benignly safe distant self); the twin peaked ‘mountain/horns’ with a replica orb in its centre; a pillar below with suggestive levels that climb up to the mountain above; and all this set upon twin supporting feet not dissimilar to an omega sign. However, this time we have a most acute additional detail that likely refers us back to my previous post concerning the Uruk seal of Taurus and Inanna.

If you look closely, you can see that a serpent has emerged from the Bull’s left ear and has eased down to wrap its jaws around the orb held between the twin peaks of the mountain atop the pillar. It appears therefore to be about to consume itself – namely, it comes from the bull’s head and is in the process of eating the creative ‘heart’ of the bull which is what the sacred orb suspended between the horns was repeatedly described as being.

To my mind, the eight-pointed star of Inanna/Venus, suspended above this configuration, gives the game away. The ‘she’ who was part of the ‘he’, the beautiful radiant aspect, the comet Venus, becomes a treasonous serpent that eats and destroys the beauteous ‘god’ who she is a part of. For the ‘heart’ or orb can also be seen as a cosmic egg from which all life emerges and is the source of creation.

That is why the fate of Taurus – the Great Bull of Heaven - is so interlinked with that of Venus – the virgin queen who becomes a dragon and kills her very own lord (state of paradise). This psychological schizophrenia, this split mind and contradictory reality that the ancients lived through, simply could not be reconciled. I believe more than any other source code, here lies the roots of how over time the female came to be seen as both glorious, radiant and much to be desired, whilst also being treacherous, serpentine and lethally dangerous to all ‘mankind’. Talk about ‘toxic masculinity’! The ancients lived a severe dose of ‘divine toxic femininity’! And the sacred bull was their battleground. Something tells me this lies at the root of why Mithraism was seemingly a men only affair…

Unfortunately, I can find no images of the two other sides of this little known stone… but I do wonder what else it might have to tell us…?

It is time to bring out on to our stage the first great hero, namely Gilgamesh.

GILGAMESH & THE BULL

In the Babylonian tradition, the celestial bull figured greatly in the Sumerian poem entitled ‘Hero in Battle’, which forms part of the earliest Gilgamesh cycle.

In the poem, Innana demands the Bull of Heaven from her father Anu so that she can wreck her vengeance on Gilgamesh who has rejected her love. Although Anu isn’t happy to hand over the bull, saying that it would have no food on the earth as ‘its pasture is on the horizon’, and ‘it can only graze where the sun rises’ (this is a mistaken translation of the meaning of Anu as the Sun. Anu is of course Chronos and ‘the horizon’ is a similar mistranslation of the crescent mountain; precisely the same problem occurs in Egyptology with Ra and his horizon in Egyptian myth!) Anu finally concedes to his daughter’s demands when she ‘flies’ into a rage.

Inanna took hold of the bull’s halter and led it down to earth (this will anon lead us into certain precessional issues), where it ravished Gilgamesh’s city, Uruk. In its insatiable hunger it devoured the pastures and palm groves, and drank the rivers dry.

Gilgamesh’s minstrel interrupts his lord while feasting and informs him of the destruction wrought by the bull. After calmly finishing their beer, Gilgamesh and his heroic companion, Enkidu, arm themselves and head out to fight the bull. After sizing up their adversary, Enkidu seized its tail and then Gilgamesh dispatched it with a blow from his axe. The bull’s carcase is then butchered; its meat distributed among the orphans of the city, its hide sent to the tanners, while its horns are made into flasks for pouring oil at Inanna’s temple.

A final crucial twist occurs at the end of the story however. After Gilgamesh and Enkidu had finished dispatching the Bull of Heaven, one of the heroes – it’s unclear if it was Gilgamesh or Enkidu - cuts off the bull’s haunch and throws it at Inanna. In response to this apparent insult, Inanna assembled her courtesans and performed rites of mourning over the bull’s haunch.

This wonderful, evocative story still makes the hairs rise on the back of my neck… because here in black and white we have the greatest example of early cosmic propaganda, in which a fundamental and vital truth about our reality is twisted on its head and covered up by ‘the victors/those of power interest’ and its meaning is both revealed and heavily veiled at the same time; and you thought they’ve only been at it since 1947! The Mythology CIA of its day did a great turn on this one! It was a veritable Gordian Knot – a confusion of apparently contradictory signals that only those equipped with the correct scissors could release and reveal (and yes the later Gordian Knot is a version of the labyrinth signifier which is deeply connected to this story as I will suggest below).

To help us better understand these cryptic clues let us turn to a classic cylinder seal commemoration of this landmark event, now held in the British Museum.

I will take you through this step-by-step.

Let us begin with our cast of suspects (this feels like an Agatha Christie murder mystery!):

‘But surely inspector, you’ve made a mistake!’ I hear you interject. ‘The character being dispatched in between them should be the Great Bull of Heaven…!’

‘Well it is… but he’s here represented in disguise’, replies Inspector Poirot, calmly straightening his inverted crescent shaped moustache in the process.

‘What are you trying to tell us now? That there only appeared to be two murders, whilst in reality there was ever only one…?’

‘Precisely my dear Watson!’ (Oops, my apologies - wrong Inspector!)

I think you get the general idea.

For those of you unfamiliar with the monstrous, legendary figure of Humbuba, the following is from Wikipedia:

Only two scenes from the Gilgamesh epic are ever depicted on Cylinder seals – the killing of the great bull as Innana tries to restrain them (as above), and the killing of Humbuba as a ‘Male Witness’ watches passively by (below, as previous) - and yes, they are the same 'murdered' entity but in two different guises. The second vignette was to gradually replace the first:

At a later date we will likely come back to the whole issue of the entrails of the bull god and their symbolic identification with the familiar concept of the Labyrinth (with of course a hidden bull at its centre). As we will with its undoubted parallels to the Perseus myth so central to the Mithraic practices of later Roman times.

I will now return once more to our 8th century BC crime-scene image above of the two Heroes slaying Humbuba.

We have already noted the presence of the Pleiades and the inverted crescent hovering above Humbuba identifying him with the Great Bull of Heaven (and also with the later installed constellation of Taurus). This could well be an error of this particular impression, but I cannot help being but struck by the strange, chaotic object above the crescent. The museum curators mumble something to the effect that the ‘line borders at top and bottom, [are] rather poorly executed in comparison with the quality of the remainder of the scene’ and then move on. I think this is their way of ignoring the obvious fact that this swirling mass evidentially breaks through the line borders and into the image below and is therefore likely intentional and an aspect of the whole scene (so as to clarify, for such a shape to appear raised above the clay it would need to be carved deeply within the scroll drum itself, and thus does not appear here by mistake). Where the perfectly round orb should be we perhaps have a depiction of chaos and breakdown.

Gilgamesh (on the left of the group of three) wears a conical helmet and an open robe, bordered with a band of squares and a fringe, over a fringed kilt, and has arrow quivers behind his shoulders; he rests one foot on Humbaba's ankle, grasps his hair in his left hand and plunges his dagger into Humbuba’s (the Bull’s) shoulder.

Enkidu (on the right) wearing an eight-pointed star on his chest, places his foot on Humbaba's knee, seizes him by the hair with his right hand and brandishes an axe above his own head.

We now have a perverse inversion of the central pillar/bull/orb god and his supporting divine twins either side. Instead, we have the god at the mercy of the twin ‘heroes’ who instead of cradling him now act as his butchers. All these arms and legs, left and rights, make this abundantly clear. The world has been turned upside down.

As for Humbaba, he is shown frontally (but only from the waist up), hair wild like snakes on end, with an odd half mask that gives the impression of an inverted crescent around his mouth and the pillar/mountain extending beneath his chin taking a form rather like an extended tongue. He kneels on one knee towards the right and with his right hand he grasps Gilgamesh's ankle and his left hand is wrapped round Enkidu's waist.

This highly distinctive pose was later to be precisely replicated in innumerable Greek images of the Gorgon Medusa – which in itself emulates the well-known ancient swastika emblem of a plasma/comet phenomenon in rotation.

As for the ‘witness’…

He stands serenely with one hand raised at an angle and pointing and the other extended out horizontally, palm up (and for those who enjoy such things, forming an angle of approximately 72°… hmmm... precession yet again…); he wears a long, double-belted skirt which is vertically striated at the top with a diagonal line across, below which is a broad band of dot-in-square patterning with a fringe at the hem.

He is pointing directly at the tasselled spade of the god Marduk on a stepped stand side by side with the wedge or stylus of the god Nabu on a square stand (these two often appeared together, each astride their serpent dragon Mušḫuššu.)

This is not the space to speak of Marduk or Nabu other than to say the first was the appointed warrior hero of the Gods (namely Mars) who brought order and creation out of chaos through his trickery, his repeated daring and his violent deeds, whilst the second is comparable to the Greek God Hermes/Roman Mercury, the mystical messenger of the gods. In some way or other Enkidu and Gilgamesh are their symbolic emissaries.

The pointing of the fore finger by the ‘witness’, the outstretched palm and angle they create; the ordered geometric squares on his clothes; Enkidu’s ninety degree left arm with its thumb and forefinger seemingly pointing directly up to heaven… I cannot help but think of Masons and the secret societies of the ancient past. This I think is no mere witness, but rather the figure in control, the manipulator behind the curtain, the orderer of the story to be told and the truth to be veiled, only available to the few in the know. Enlil has a lot to answer for! (That’s effectively him by the way, standing there in plainclothes so to speak, pointing his fingers, giving commands from behind the curtain, waiting to receive the horned head of the bull/Humbuba tied up in a sack i.e. knowledge, especially of the future, hidden from prying eyes other than his and his kind?).

And what of that haunch of the bull, cut off and tossed at the goddess Inanna?

Well, there is an intriguing parallel to this bizarre incident in Egyptian mortuary traditions where a bull’s foreleg is one of the chief offerings made to the deceased. And it can be no coincidence that the Egyptians placed their constellation of the Bull’s Foreleg right at the very heart of the Northern circumpolar stars - which the Babylonians also envisioned as their funerary Wagon – the very location of the original Great Bull of Heaven phenomenon.

Meanwhile we have Taurus cut in half. I will come back to this matter in detail when we look at Ares-Aries. For now, let us merely note that upon the bull’s leg suspended at the northern centre, the small enigmatic figure of a Ram sits silently attached… staring ‘down’ at its larger mirror Aries and that still strangely whole Egyptian Taurus the bull, facing in the ‘wrong’ direction…

How our plot continues to thicken!

For now, I will simply leave you with the suggestion that thanks to the true secret of precession, that the cutting in half of the bull and the change in its orientation may well be a symbolic representation of what happened to it in the past and also how one day, perhaps sooner than we think, this is the way it will return – with no warning - head first out of the darkness!

The idea of the great god being a sky-bull can be found on artifacts distributed throughout the Ancient Near East. On one such object, a square pedestal stone from Tayma in Saudi Arabia and dated to around 600-800 BCE, we find a most intriguing story.

Scholars assess that this Arabic artifact reveals how - many centuries on from the time we are exploring - both Egyptian and principally Babylonian influences made their way via Syria to Northern Arabia. There, three principle gods were absorbed: Salm, (namely our Chronos, but Anu to the Sumerians), Śangilā (the great on-its-back bull’s crescent aspect associated with the deity Sin); and Ášimā (Inanna namely Ishtar namely the comet Venus). This was the near universal sacred trinity of the time in Mesopotamia.

Present day interpretations by scholars of myths concerning this trinity make absolutely no sense, however – with them agreeing that the myths tell us that Sin (the Moon) was the father of Shamash (the Sun) and also of Ishtar/Inanna (Venus the planet). However, this was not always the case, as for example late 19th century scholar Peter Jensen in his ground-breaking study of Mesopotamian astronomy, Die Kosmologie der Babylonier, unequivocally identified the crescentine god Sin as the planet Saturn i.e. Chronos. Thus, if we think in terms of our story – that the Great Bull/Chronos (Sin) was the carrier/cradle for Shamash/Chronos (the orb) who spawned a daughter Venus (the comet), then we start getting somewhere. The stone from Tayma itself makes all this patently clear.

That this fascinating design is cubed is of immediate interest considering how Chronos/Saturn was the ‘cubed god’ (as witnessed by the sacred cubed Kaaba and its black meteorite stone at Mecca).

Of even greater note, all the usual suspects are again gathered together in one meaningful place, albeit at a much later date, and all etched in the traditional Babylonian style – the sacred head of the bull; the orb located in the crescent of its horns; the comet goddess Venus (shown both in her winged and magnificent – if menacing - state when in close proximity to earth and also as an eight pointed star – her more benignly safe distant self); the twin peaked ‘mountain/horns’ with a replica orb in its centre; a pillar below with suggestive levels that climb up to the mountain above; and all this set upon twin supporting feet not dissimilar to an omega sign. However, this time we have a most acute additional detail that likely refers us back to my previous post concerning the Uruk seal of Taurus and Inanna.

If you look closely, you can see that a serpent has emerged from the Bull’s left ear and has eased down to wrap its jaws around the orb held between the twin peaks of the mountain atop the pillar. It appears therefore to be about to consume itself – namely, it comes from the bull’s head and is in the process of eating the creative ‘heart’ of the bull which is what the sacred orb suspended between the horns was repeatedly described as being.

To my mind, the eight-pointed star of Inanna/Venus, suspended above this configuration, gives the game away. The ‘she’ who was part of the ‘he’, the beautiful radiant aspect, the comet Venus, becomes a treasonous serpent that eats and destroys the beauteous ‘god’ who she is a part of. For the ‘heart’ or orb can also be seen as a cosmic egg from which all life emerges and is the source of creation.

That is why the fate of Taurus – the Great Bull of Heaven - is so interlinked with that of Venus – the virgin queen who becomes a dragon and kills her very own lord (state of paradise). This psychological schizophrenia, this split mind and contradictory reality that the ancients lived through, simply could not be reconciled. I believe more than any other source code, here lies the roots of how over time the female came to be seen as both glorious, radiant and much to be desired, whilst also being treacherous, serpentine and lethally dangerous to all ‘mankind’. Talk about ‘toxic masculinity’! The ancients lived a severe dose of ‘divine toxic femininity’! And the sacred bull was their battleground. Something tells me this lies at the root of why Mithraism was seemingly a men only affair…

Unfortunately, I can find no images of the two other sides of this little known stone… but I do wonder what else it might have to tell us…?

It is time to bring out on to our stage the first great hero, namely Gilgamesh.

GILGAMESH & THE BULL

In the Babylonian tradition, the celestial bull figured greatly in the Sumerian poem entitled ‘Hero in Battle’, which forms part of the earliest Gilgamesh cycle.

In the poem, Innana demands the Bull of Heaven from her father Anu so that she can wreck her vengeance on Gilgamesh who has rejected her love. Although Anu isn’t happy to hand over the bull, saying that it would have no food on the earth as ‘its pasture is on the horizon’, and ‘it can only graze where the sun rises’ (this is a mistaken translation of the meaning of Anu as the Sun. Anu is of course Chronos and ‘the horizon’ is a similar mistranslation of the crescent mountain; precisely the same problem occurs in Egyptology with Ra and his horizon in Egyptian myth!) Anu finally concedes to his daughter’s demands when she ‘flies’ into a rage.

Inanna took hold of the bull’s halter and led it down to earth (this will anon lead us into certain precessional issues), where it ravished Gilgamesh’s city, Uruk. In its insatiable hunger it devoured the pastures and palm groves, and drank the rivers dry.

Gilgamesh’s minstrel interrupts his lord while feasting and informs him of the destruction wrought by the bull. After calmly finishing their beer, Gilgamesh and his heroic companion, Enkidu, arm themselves and head out to fight the bull. After sizing up their adversary, Enkidu seized its tail and then Gilgamesh dispatched it with a blow from his axe. The bull’s carcase is then butchered; its meat distributed among the orphans of the city, its hide sent to the tanners, while its horns are made into flasks for pouring oil at Inanna’s temple.

A final crucial twist occurs at the end of the story however. After Gilgamesh and Enkidu had finished dispatching the Bull of Heaven, one of the heroes – it’s unclear if it was Gilgamesh or Enkidu - cuts off the bull’s haunch and throws it at Inanna. In response to this apparent insult, Inanna assembled her courtesans and performed rites of mourning over the bull’s haunch.

This wonderful, evocative story still makes the hairs rise on the back of my neck… because here in black and white we have the greatest example of early cosmic propaganda, in which a fundamental and vital truth about our reality is twisted on its head and covered up by ‘the victors/those of power interest’ and its meaning is both revealed and heavily veiled at the same time; and you thought they’ve only been at it since 1947! The Mythology CIA of its day did a great turn on this one! It was a veritable Gordian Knot – a confusion of apparently contradictory signals that only those equipped with the correct scissors could release and reveal (and yes the later Gordian Knot is a version of the labyrinth signifier which is deeply connected to this story as I will suggest below).

To help us better understand these cryptic clues let us turn to a classic cylinder seal commemoration of this landmark event, now held in the British Museum.

I will take you through this step-by-step.

Let us begin with our cast of suspects (this feels like an Agatha Christie murder mystery!):

- To our left we have our ‘Witness’

- Next in line comes Mr. ‘Gilgamesh’, our principle suspect.

- On the far fright, his accomplice, Mr. ‘Enkidu’.

- In between and above them hang the symbols for the Pleiades as well as the ever-present crescent on its back…

- Therefore in between our two partners in crime … (drum roll) … we have the victim of this terrible deed… and he is … (further drum roll) … HUMBUBA (or Huwawa, if you prefer the earlier Sumerian).

‘But surely inspector, you’ve made a mistake!’ I hear you interject. ‘The character being dispatched in between them should be the Great Bull of Heaven…!’

‘Well it is… but he’s here represented in disguise’, replies Inspector Poirot, calmly straightening his inverted crescent shaped moustache in the process.

‘What are you trying to tell us now? That there only appeared to be two murders, whilst in reality there was ever only one…?’

‘Precisely my dear Watson!’ (Oops, my apologies - wrong Inspector!)

I think you get the general idea.

For those of you unfamiliar with the monstrous, legendary figure of Humbuba, the following is from Wikipedia:

Humbaba