You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Righteous Mind - Jonathan Haidt and Liberal vs Conservative ethics

- Thread starter Laura

- Start date

A very good read. Having made it to Chapter 6, here are my thoughts so far.

From what I've read so far it seems that much can be divided into two ideas: Haidt's 'first principle of moral psychology' - that intuition comes first, strategic reasoning second, and his second principle of moral psychology - that there is more to morality than harm and fairness.

Intuition comes first, strategic reasoning second

The bottom line for Haidt is that intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second.

I also found his remarks on man's constant lying to himself and others to be especially interesting (p. 62-63):

This is a recurring theme throughout the chapters. But how does it fit with morality? Because, as Haidt points out, our emotional reasoning is fundamentally moral, and they incline us to act more like politicians seeking votes than scientists seeking truth. And they act astonishingly fast. He writes that we are 'obsessively concerned' with making a good impression, and this distorts our thinking to an astonishing degree:

• Conscious reasoning functions like a press secretary who automatically justifies any position taken by the president.

• With the help of our press secretary, we are able to lie and cheat often, and then cover it up so effectively that we convince even ourselves.

• Reasoning can take us to almost any conclusion we want to reach, because we ask “Can I believe it?” when we want to believe something, but “Must I believe it?” when we don’t want to believe. The answer is almost always yes to the first question and no to the second.

• In moral and political matters we are often groupish, rather than selfish. We deploy our reasoning skills to support our team, and to demonstrate commitment to our team.

After identifying the 'elephant' (lightning-fast emotional and intuitive reactions to what is moral vs immoral) he asks 'when does the elephant listen to reason?'

There is more to morality than harm and fairness

Haidt begins the book with a presentation of the foundations of Western moral psychology, and the struggle to discover both what morality is as well as a universal framework that transcends societal limitations. Rather than seeing people as blank slates, or as seeing morality as hard-wired, by 1987 most American psychologists assumed that children figured out morality in stages, based on the fundamental notion of harm. By learning what harmed them and what could harm others, children were assumed to become more 'liberal' in their morality over the years, with the primary focus of morality being the elimination of suffering for themselves and others. Psychologists Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg ironed out this view of morality and it was found to be politically useful by the Left.

Anthropologists steeped in the study of foreign cultures had a very different take on the issue, seeing as how those cultures conceived of morality across a much wider spectrum of behaviors. So, along came an anthropologist from the University of Chicago, Richard Shweder. He presented a basic dichotomy with which to view society's moral skeletons. These were individualistic vs. sociocentric cultures, and he thought that Kohlberg and Piaget's moral frameworks were biased by the West's individualistic morality. Haidt writes:

Shweder's research demonstrated that there was much more to morality than the issue of harm, and it drew a lot of backlash. Haidt set out to interview people from across cultures to determine who was right. He conducted studies in Brazil and Philadelphia. Through Haidt's studies he found that, not only was culture an issue in determining morality, but social class and levels of education were as well. For the West and in upper class/educated places in Brazil, morality was very restricted:

With these findings Haidt summed up what constituted his early thinking on the nature of morality:

Later on Haidt returns to Shweder's thinking, and draws from it a far more nuanced picture of morality than the restricted one in upper class, Western, and educated circles. While his first principle of moral psychology is that intuition comes first, strategic reasoning second, his second basic principle is that there is more to morality than harm and fairness. He identifies three distinct ethics besides these. These are autonomy, community, and divinity.

Divinity is the concept that men, women and children are all souled beings, that our lives are intrinsically meaningful because we are more than a physical body.

Automony is the idea that we have individual wants, needs, desires, and should be free to meet them as we move through life. This is the dominant ethic in individualist societies.

Community is the idea that we must submit our desires, wants, and needs to those of the larger community.

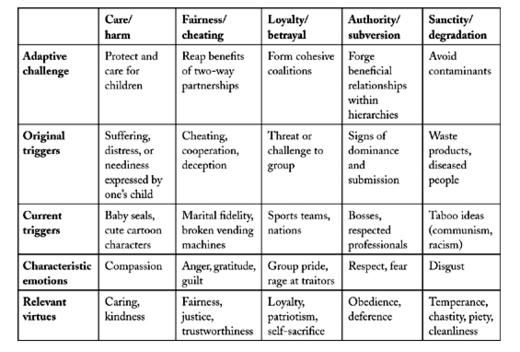

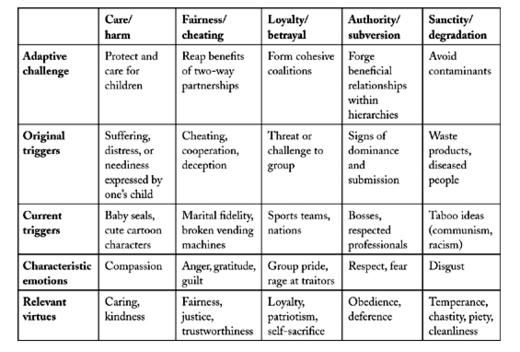

Haidt then began constructing a framework with which to view the full picture of morality - the triggers for emotional expression as well as the dominant categories which the emotions attempt to protect:

It is easy to see how a restricted view of 'harm avoidance' on the part of the Left has led to such a warped society, and why conservatives who cherish loyalty, authority and sanctity are getting riled up into a storm. Given what Haidt has to say about education and being in a high social class restricting one's moral compass, it is interesting that these people also make up a large part of the 'Left'. An obsessive focus on 'harm avoidance' is a thinking error, and like the serial killers in the recommended reading, it seems the Left has embraced this thinking error to the point of becoming homicidal maniacs.

From what I've read so far it seems that much can be divided into two ideas: Haidt's 'first principle of moral psychology' - that intuition comes first, strategic reasoning second, and his second principle of moral psychology - that there is more to morality than harm and fairness.

Intuition comes first, strategic reasoning second

The bottom line for Haidt is that intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second.

p. 38 said:It took me years to appreciate fully the implications of Margolis's ideas. Part of the problem was that my thinking was entrenched in a prevalent but useless dichotomy between cognition and emotion. After failing repeatedly to get cognition to act independently of emotion, I began to realize that the dichotomy made no sense. Cognition just refers to information processing, which includes higher cognition (such as conscious reasoning) as well as lower cognition (such as visual perception and memory retrieval).

Emotion is a bit harder to define. Emotions were long thought to be dumb and visceral, but beginning in the 1980s, scientists increasingly recognized that emotions were filled with cognition. Emotions occur in steps, the first of which is to appraise something that just happened based on whether it advanced or hindered your goals. These appraisals are a kind of information processing; they are cognitions. When an appraisal program detects particular input patterns, it launches a set of changes in your brain that prepare you to respond appropriately. For example, if you hear someone running up behind you on a dark street, your fear system detects a threat and triggers your sympathetic nervous system, firing up the fight-or-flight response, cranking up your heart rate, and widening your pupils to help you take in more information.

Emotions are not dumb. Damasio's patients made terrible decisions because they were deprived of emotional input into their decision making. Emotions are a kind of information processing.39 Contrasting emotion with cognition is therefore as pointless as contrasting rain with weather, or cars with vehicles. [...]

Damasio’s interpretation was that gut feelings and bodily reactions were necessary to think rationally, and that one job of the vmPFC was to integrate those gut feelings into a person’s conscious deliberations. When you weigh the advantages and disadvantages of murdering your parents … you can’t even do it, because feelings of horror come rushing in through the vmPFC.

But Damasio’s patients could think about anything, with no filtering or coloring from their emotions. With the vmPFC shut down, every option at every moment felt as good as every other. The only way to make a decision was to examine each option, weighing the pros and cons using conscious, verbal reasoning. If you’ve ever shopped for an appliance about which you have few feelings—say, a washing machine—you know how hard it can be once the number of options exceeds six or seven (which is the capacity of our short-term memory). Just imagine what your life would be like if at every moment, in every social situation, picking the right thing to do or say became like picking the best washing machine among ten options, minute after minute, day after day. You’d make foolish decisions too.

I also found his remarks on man's constant lying to himself and others to be especially interesting (p. 62-63):

On February 3, 2007, shortly before lunch, I discovered that I was a chronic liar. I was at home, writing a review article on moral psychology, when my wife, Jayne, walked by my desk. In passing, she asked me not to leave dirty dishes on the counter where she prepared our baby’s food. Her request was polite but its tone added a postscript: “As I have asked you a hundred times before.”

My mouth started moving before hers had stopped. Words came out. Those words linked themselves up to say something about the baby having woken up at the same time that our elderly dog barked to ask for a walk and I’m sorry but I just put my breakfast dishes down wherever I could. In my family, caring for a hungry baby and an incontinent dog is a surefire excuse, so I was acquitted.

Jayne left the room and I continued working. I was writing about the three basic principles of moral psychology. The first principle is Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second. That’s a six-word summary of the social intuitionist model. [...]

So there I was at my desk, writing about how people automatically fabricate justifications of their gut feelings, when suddenly I realized that I had just done the same thing with my wife. I disliked being criticized, and I had felt a flash of negativity by the time Jayne had gotten to her third word (“Can you not …”). Even before I knew why she was criticizing me, I knew I disagreed with her (because intuitions come first). The instant I knew the content of the criticism (“… leave dirty dishes on the …”), my inner lawyer went to work searching for an excuse (strategic reasoning second). It’s true that I had eaten breakfast, given Max his first bottle, and let Andy out for his first walk, but these events had all happened at separate times. Only when my wife criticized me did I merge them into a composite image of a harried father with too few hands, and I created this fabrication by the time she had completed her one-sentence criticism (“… counter where I make baby food?”). I then lied so quickly and convincingly that my wife and I both believed me.

This is a recurring theme throughout the chapters. But how does it fit with morality? Because, as Haidt points out, our emotional reasoning is fundamentally moral, and they incline us to act more like politicians seeking votes than scientists seeking truth. And they act astonishingly fast. He writes that we are 'obsessively concerned' with making a good impression, and this distorts our thinking to an astonishing degree:

• Conscious reasoning functions like a press secretary who automatically justifies any position taken by the president.

• With the help of our press secretary, we are able to lie and cheat often, and then cover it up so effectively that we convince even ourselves.

• Reasoning can take us to almost any conclusion we want to reach, because we ask “Can I believe it?” when we want to believe something, but “Must I believe it?” when we don’t want to believe. The answer is almost always yes to the first question and no to the second.

• In moral and political matters we are often groupish, rather than selfish. We deploy our reasoning skills to support our team, and to demonstrate commitment to our team.

After identifying the 'elephant' (lightning-fast emotional and intuitive reactions to what is moral vs immoral) he asks 'when does the elephant listen to reason?'

p. 78 said:When does the elephant listen to reason? The main way that we change our minds on moral issues is by interacting with other people. We are terrible at seeking evidence that challenges our own beliefs, but other people do us this favor, just as we are quite good at finding errors in other people’s beliefs. When discussions are hostile, the odds of change are slight. The elephant leans away from the opponent, and the rider works frantically to rebut the opponent’s charges.

But if there is affection, admiration, or a desire to please the other person, then the elephant leans toward that person and the rider tries to find the truth in the other person’s arguments. The elephant may not often change its direction in response to objections from its own rider, but it is easily steered by the mere presence of friendly elephants (that’s the social persuasion link in the social intuitionist model) or by good arguments given to it by the riders of those friendly elephants (that’s the reasoned persuasion link).

There is more to morality than harm and fairness

Haidt begins the book with a presentation of the foundations of Western moral psychology, and the struggle to discover both what morality is as well as a universal framework that transcends societal limitations. Rather than seeing people as blank slates, or as seeing morality as hard-wired, by 1987 most American psychologists assumed that children figured out morality in stages, based on the fundamental notion of harm. By learning what harmed them and what could harm others, children were assumed to become more 'liberal' in their morality over the years, with the primary focus of morality being the elimination of suffering for themselves and others. Psychologists Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg ironed out this view of morality and it was found to be politically useful by the Left.

Anthropologists steeped in the study of foreign cultures had a very different take on the issue, seeing as how those cultures conceived of morality across a much wider spectrum of behaviors. So, along came an anthropologist from the University of Chicago, Richard Shweder. He presented a basic dichotomy with which to view society's moral skeletons. These were individualistic vs. sociocentric cultures, and he thought that Kohlberg and Piaget's moral frameworks were biased by the West's individualistic morality. Haidt writes:

p. 15 said:Shweder offered a simple idea to explain why the self differs so much across cultures: all societies must resolve a small set of questions about how to order society, the most important being how to balance the needs of individuals and groups. There seem to be just two primary ways of answering this question. Most societies have chosen the sociocentric answer, placing the needs of groups and institutions first, and subordinating the needs of individuals. In contrast, the individualistic answer places individuals at the center and makes society a servant of the individual.

Shweder's research demonstrated that there was much more to morality than the issue of harm, and it drew a lot of backlash. Haidt set out to interview people from across cultures to determine who was right. He conducted studies in Brazil and Philadelphia. Through Haidt's studies he found that, not only was culture an issue in determining morality, but social class and levels of education were as well. For the West and in upper class/educated places in Brazil, morality was very restricted:

p.20-24 said:I started writing very short stories about people who do offensive things, but do them in such a way that nobody is harmed. I called these stories “harmless taboo violations,” and you read two of them at the start of this chapter (about dog-eating and chicken- … eating). I made up dozens of these stories but quickly found that the ones that worked best fell into two categories: disgust and disrespect. If you want to give people a quick flash of revulsion but deprive them of any victim they can use to justify moral condemnation, ask them about people who do disgusting or disrespectful things, but make sure the actions are done in private so that nobody else is offended. For example, one of my disrespect stories was: “A woman is cleaning out her closet, and she finds her old American flag. She doesn’t want the flag anymore, so she cuts it up into pieces and uses the rags to clean her bathroom.”

My idea was to give adults and children stories that pitted gut feelings about important cultural norms against reasoning about harmlessness, and then see which force was stronger. [...]

When I returned to Philadelphia, I trained my own team of interviewers and supervised the data collection for the four groups of subjects in Philadelphia. The design of the study was therefore what we call “three by two by two,” meaning that we had three cities, and in each city we had two levels of social class (high and low), and within each social class we had two age groups: children (ages ten to twelve) and adults (ages eighteen to twenty-eight). That made for twelve groups in all, with thirty people in each group, for a total of 360 interviews. This large number of subjects allowed me to run statistical tests to examine the independent effects of city, social class, and age. I predicted that Philadelphia would be the most individualistic of the three cities (and therefore the most Turiel-like) and Recife would be the most sociocentric.

[...]

First, all four of my Philadelphia groups confirmed Turiel’s finding that Americans make a big distinction between moral and conventional violations. I used two stories taken directly from Turiel’s research: a girl pushes a boy off a swing (that’s a clear moral violation) and a boy refuses to wear a school uniform (that’s a conventional violation). This validated my methods. It meant that any differences I found on the harmless taboo stories could not be attributed to some quirk about the way I phrased the probe questions or trained my interviewers. The upper-class Brazilians looked just like the Americans on these stories. But the working-class Brazilian kids usually thought that it was wrong, and universally wrong, to break the social convention and not wear the uniform. In Recife in particular, the working-class kids judged the uniform rebel in exactly the same way they judged the swing-pusher. This pattern supported Shweder: the size of the moral-conventional distinction varied across cultural groups.

The second thing I found was that people responded to the harmless taboo stories just as Shweder had predicted: the upper-class Philadelphians judged them to be violations of social conventions, and the lower-class Recifeans judged them to be moral violations. There were separate significant effects of city (Porto Alegreans moralized more than Philadelphians, and Recifeans moralized more than Porto Alegreans), of social class (lower-class groups moralized more than upper-class groups), and of age (children moralized more than adults). Unexpectedly, the effect of social class was much larger than the effect of city. In other words, well-educated people in all three cities were more similar to each other than they were to their lower-class neighbors. I had flown five thousand miles south to search for moral variation when in fact there was more to be found a few blocks west of campus, in the poor neighborhood surrounding my university.

My third finding was that all the differences I found held up when I controlled for perceptions of harm. I had included a probe question that directly asked, after each story: “Do you think anyone was harmed by what [the person in the story] did?” If Shweder’s findings were caused by perceptions of hidden victims (as Turiel proposed), then my cross-cultural differences should have disappeared when I removed the subjects who said yes to this question. But when I filtered out these people, the cultural differences got bigger, not smaller. This was very strong support for Shweder’s claim that the moral domain goes far beyond harm. Most of my subjects said that the harmless-taboo violations were universally wrong even though they harmed nobody.

In other words, Shweder won the debate. I had replicated Turiel’s findings using Turiel’s methods on people like me—educated Westerners raised in an individualistic culture—but had confirmed Shweder’s claim that Turiel’s theory didn’t travel well. The moral domain varied across nations and social classes. For most of the people in my study, the moral domain extended well beyond issues of harm and fairness.

It was hard to see how a rationalist could explain these results. How could children self-construct their moral knowledge about disgust and disrespect from their private analyses of harmfulness? There must be other sources of moral knowledge, including cultural learning (as Shweder argued), or innate moral intuitions about disgust and disrespect (as I began to argue years later).

With these findings Haidt summed up what constituted his early thinking on the nature of morality:

p.29 said:Where does morality come from? The two most common answers have long been that it is innate (the nativist answer) or that it comes from childhood learning (the empiricist answer). In this chapter I considered a third possibility, the rationalist answer, which dominated moral psychology when I entered the field: that morality is self-constructed by children on the basis of their experiences with harm. Kids know that harm is wrong because they hate to be harmed, and they gradually come to see that it is therefore wrong to harm others, which leads them to understand fairness and eventually justice. I explained why I came to reject this answer after conducting research in Brazil and the United States. I concluded instead that:

• The moral domain varies by culture. It is unusually narrow in Western, educated, and individualistic cultures. Sociocentric cultures broaden the moral domain to encompass and regulate more aspects of life.

• People sometimes have gut feelings—particularly about disgust and disrespect—that can drive their reasoning. Moral reasoning is sometimes a post hoc fabrication.

• Morality can’t be entirely self-constructed by children based on their growing understanding of harm. Cultural learning or guidance must play a larger role than rationalist theories had given it.

Later on Haidt returns to Shweder's thinking, and draws from it a far more nuanced picture of morality than the restricted one in upper class, Western, and educated circles. While his first principle of moral psychology is that intuition comes first, strategic reasoning second, his second basic principle is that there is more to morality than harm and fairness. He identifies three distinct ethics besides these. These are autonomy, community, and divinity.

Divinity is the concept that men, women and children are all souled beings, that our lives are intrinsically meaningful because we are more than a physical body.

Automony is the idea that we have individual wants, needs, desires, and should be free to meet them as we move through life. This is the dominant ethic in individualist societies.

Community is the idea that we must submit our desires, wants, and needs to those of the larger community.

Haidt then began constructing a framework with which to view the full picture of morality - the triggers for emotional expression as well as the dominant categories which the emotions attempt to protect:

It is easy to see how a restricted view of 'harm avoidance' on the part of the Left has led to such a warped society, and why conservatives who cherish loyalty, authority and sanctity are getting riled up into a storm. Given what Haidt has to say about education and being in a high social class restricting one's moral compass, it is interesting that these people also make up a large part of the 'Left'. An obsessive focus on 'harm avoidance' is a thinking error, and like the serial killers in the recommended reading, it seems the Left has embraced this thinking error to the point of becoming homicidal maniacs.

Great post Hesper.

I just want to point out that the chart posted is one where Haidt is proposing the evolutionary innate tendency that is the frame for particular moral emotions, i.e. the "adaptive challenge" that evolving humans had to deal with in order to survive and the things that triggered those emotions. Obviously, the same triggers don't operate today, usually, but there are new triggers.

In the second half of the book he brings in the 6th flavor which was necessary in order to understand the US-type liberal.

I just want to point out that the chart posted is one where Haidt is proposing the evolutionary innate tendency that is the frame for particular moral emotions, i.e. the "adaptive challenge" that evolving humans had to deal with in order to survive and the things that triggered those emotions. Obviously, the same triggers don't operate today, usually, but there are new triggers.

In the second half of the book he brings in the 6th flavor which was necessary in order to understand the US-type liberal.

Just for grins, I took the five dimensional morality test off of the yourmorals site. According to that, overall I'm neither liberal, nor conservative, which is pretty much what I expected. I didn't think much of the loyalty questions, they asked you how much you would support your sports team or your political party, and I'm neither interested in sports nor political parties, so I scored those questions very low. I think there were a couple of questions about military service, which I despise in it's current form, so I pretty much answered strongly disagree to the whole section. Generally loyalty to various organizations is what gets people killed or coopted into nefarious activities, but I do value my "ingroup" if they seem to be trustworthy. If the questions weren't so stupid, I probably would've split the difference between liberals and conservatives.

Attachments

luc said:Laura said:One wonders, of course, if these "moral foundations" might reflect STS/STO orientations and/or possibilities of OP vs souled types?

I haven't read the book yet, just saw a few videos (parts). I thought the lack of "disgust" in liberal types is interesting, because as I understand it, this is something "directly felt moral disgust". Of course, the libs often call this "intolerant" because in their minds, fairness and freedom from harm trump everything. But maybe this disgust sensitivity is more like a functioning conscience and a "taste" for spiritual degeneration? Like, if you see a gay pride parade, you don't think "tolerance"; you are disgusted. When you hear about children being fed hormones because they claim do be transgender, you don't think "equal rights"; you are disgusted. And so on.

Of course, nobody is immune against the staggering amount of programming in our society, but at least some people may have some sort of a BS detection system (shades of the higher emotional center?) that might be helpful if listened to. Dunno, just some thoughts.

I was born with a very finely-tuned BS detector. As a result, I always found it hard to really fit in with any group whether left or right leaning or anything else. Conservatives, or example, don't understand the level of need those who come from bad family backgrounds have. They don't get that not everyone has an uncle who'll pull the strings to get them that first job, or what moving around every year or two does to a kid's ability to plan for the future. How utterly demoralizing low level jobs can be for an intelligent individual who has no other options at the time. However, Liberals' promotion of victim politics is absolutely toxic. The welfare state/poverty industry really do seem to do more harm than good. More funding invariably seems to lead to more corruption. Some of the worst-performing education districts are those with the highest per-pupil funding. Conservatives are right that the stable family unit breeds success, while liberals are right in pointing out the failings of that social structure (such as the lack of support for those who don't have much family, or horrible extremes such as honor killings).

I've come to think that the proper political spectrum is between extremes of authoritarianism vs self-rule, and between what I see as the hive mind vs individualism. As you said, nobody is fully immune to the programming, and we did evolve for hundreds of thousands of years as tribes, or belonging in social groups. No man is an island, as they say. The key is just try to be more aware of this programming and not necessarily fight against it, but try to harness it. Such as by seeking out relatively like-minded people, but being aware of the risks of entering an echo chamber.

CdeSouza said:luc said:Laura said:One wonders, of course, if these "moral foundations" might reflect STS/STO orientations and/or possibilities of OP vs souled types?

I haven't read the book yet, just saw a few videos (parts). I thought the lack of "disgust" in liberal types is interesting, because as I understand it, this is something "directly felt moral disgust". Of course, the libs often call this "intolerant" because in their minds, fairness and freedom from harm trump everything. But maybe this disgust sensitivity is more like a functioning conscience and a "taste" for spiritual degeneration? Like, if you see a gay pride parade, you don't think "tolerance"; you are disgusted. When you hear about children being fed hormones because they claim do be transgender, you don't think "equal rights"; you are disgusted. And so on.

Of course, nobody is immune against the staggering amount of programming in our society, but at least some people may have some sort of a BS detection system (shades of the higher emotional center?) that might be helpful if listened to. Dunno, just some thoughts.

I was born with a very finely-tuned BS detector. As a result, I always found it hard to really fit in with any group whether left or right leaning or anything else. Conservatives, or example, don't understand the level of need those who come from bad family backgrounds have. They don't get that not everyone has an uncle who'll pull the strings to get them that first job, or what moving around every year or two does to a kid's ability to plan for the future. How utterly demoralizing low level jobs can be for an intelligent individual who has no other options at the time. However, Liberals' promotion of victim politics is absolutely toxic. The welfare state/poverty industry really do seem to do more harm than good. More funding invariably seems to lead to more corruption. Some of the worst-performing education districts are those with the highest per-pupil funding. Conservatives are right that the stable family unit breeds success, while liberals are right in pointing out the failings of that social structure (such as the lack of support for those who don't have much family, or horrible extremes such as honor killings).

I've come to think that the proper political spectrum is between extremes of authoritarianism vs self-rule, and between what I see as the hive mind vs individualism. As you said, nobody is fully immune to the programming, and we did evolve for hundreds of thousands of years as tribes, or belonging in social groups. No man is an island, as they say. The key is just try to be more aware of this programming and not necessarily fight against it, but try to harness it. Such as by seeking out relatively like-minded people, but being aware of the risks of entering an echo chamber.

Have you read Haidt's book, CdeSouza? From your post above, I think you'd really like it if not. By the end of the book, he pretty much sums up the principle behind your position: each part of the political spectrum has its pros and cons, and each acts as a balance for the blind spots of the other. The way Haidt describes it, we are selfish chimps with an overlay of hive-mind bees. The hivi-mind is what actually makes us human to a great degree: competition among groups is what gave us our morality, so to speak. What he doesn't delve into so much is the significance of the individual within the group (Peterson talks more about this).

The way I've come to see it, thanks to Haidt and all the stuff I've read and thought about before him, is that our values are nested within more basic values. At the root is the value for the body, self-preservation. That's our inner chimp, competitive, selfish. On top of that is our value for our group, and for the preservation of the group. That's our inner bee, more concerned about appearing virtuous than actually being so, but still with the advantage that we get along within the group and create a stable, functioning society. And you can't be a functioning hive without still valuing the individual bodies that make it up. So the value for the hive goes along with the value of the chimp, even if you can get extremes, like violence or needless sacrifice of the individual for the group.

But on top of that (and probably more rare statistically) is the value for the self as rational and valuable in itself. That's our inner ideal human, perhaps. Without it, we would only be groupish automatons. So when the society is wrong, it's the role of some individuals to challenge the group, even if that means putting the body at risk, and the identity of the group in its current form. The values leading to such a choice will still be rooted in our biologically shaped moral foundations. But for such a person, truth and integrity become more important than selfishness and groupishness for their sake. And the best way forward is to find the path that preserves all three levels: body, group, and "self".

Great book. Haidt brings things back to the center ground. Poor guy, few will listen to him as things become increasingly polarized, but all in this network should read his work to strengthen their understanding of 'left-right' in politics.

Laura said:Great post Hesper.

I just want to point out that the chart posted is one where Haidt is proposing the evolutionary innate tendency that is the frame for particular moral emotions, i.e. the "adaptive challenge" that evolving humans had to deal with in order to survive and the things that triggered those emotions. Obviously, the same triggers don't operate today, usually, but there are new triggers.

In the second half of the book he brings in the 6th flavor which was necessary in order to understand the US-type liberal.

Thank you for the correction Laura, I've just finished the last half of the book and have tried to outline his final version of the second principle of moral psychology: That there is more to morality than harm and fairness. Haidt writes that human morality has at least 6 foundations, they are rooted in our evolutionary history, and they are as follows:

- Care/Harm: cherishing and protecting others

- Fairness/Cheating: rendering justice according to shared rules

- Liberty/Oppression: the loathing of tyranny; opposite of oppression

- Loyalty/Betrayal: standing with your group, family, nation

- Authority/Subversion: submitting to tradition and legitimate author

- Sanctity/Degradation: abhorrence for disgusting things, foods, actions

Liberals have the first three in spades, while Conservatives have the full six.

Care/Harm: cherishing and protecting others

The origins of this foundation are in protecting and raising children. As Haidt argues further into part 3 of his book this 'nest-like' quality of human nature is one of the fundamental principles that led us to becoming 'ultrasocial' versus social like chimps and wolves. We had a nest, offspring that required significant amounts of time and energy raising, and intragroup conflict. These pressures led to the more 'hive-like' qualities that govern our overall behavior, and perhaps to the more 'mature' foundations that Liberals do not share with Conservatives. After all, the care/harm foundation is something we share with primates and other animals that raise their children to a certain stage of development.

Fairness/Cheating: rendering justice according to shared rules

Many animals have to contend with various forms of cheating. In ant and bee colonies workers sometimes lay eggs though the queen is the only one allowed to do so. Other workers will then eat the eggs as punishment to those who attempt to take the queen's role and not do their own job. Humans, as ultrasocial animals, are under pressure to work in complex environments with those who repay us and to avoid those who take advantage. Both Liberals and Conservatives share this foundation, but it plays out differently in the US Liberal/Conservative divide. As Haidt points out,

p. 160 said:Everyone cares about fairness, but there are two major kinds. On the left, fairness often implies equality, but on the right it means proportionality—people should be rewarded in proportion to what they contribute, even if that guarantees unequal outcomes.

This moral ethic also primes us to punish those who cheat. Haidt provides an interesting example of this when he writes about a Swiss study in which students were invited to play twelve rounds in an 'investment' game. The students were each given 3 partners and each were given 20 tokens on each round. They could keep all of their tokens or invest them into the groups common bank. The experimenters would then multiply the pot 1.6 times and divide that among all four players. If someone contributed nothing then they'd get a share of the pot plus all of their originals tokens each round, so this was clearly the way to make the most coins.

But after the 6th round the experimenters switch it up. Haidt writes:

p. 208 said:But here’s the reason this is such a brilliant study: After the sixth round, the experimenters told subjects that there was a new rule: After learning how much each of your partners contributed on each round, you now would have the option of paying, with your own tokens, to punish specific other players. Every token you paid to punish would take three tokens away from the player you punished.

For Homo economicus, the right course of action is once again perfectly clear: never pay to punish, because you will never again play with those three partners, so there is no chance to benefit from reciprocity or from gaining a tough reputation. Yet remarkably, 84 percent of subjects paid to punish, at least once. And even more remarkably, cooperation skyrocketed on the very first round where punishment was allowed, and it kept on climbing. By the twelfth round, the average contribution was fifteen tokens.46 Punishing bad behavior promotes virtue and benefits the group. And just as Glaucon argued in his ring of Gyges example, when the threat of punishment is removed, people behave selfishly.

Why did most players pay to punish? In part, because it felt good to do so. We hate to see people take without giving. We want to see cheaters and slackers “get what’s coming to them.”

So Liberals are more concerned with punishing those in authority who cheat, and more lax when it comes to those with less power cheating. Given what Haidt discussed before, with intuition coming first and strategic reasoning second, these first two foundations go a long way toward explaining why the Left hates capitalism. Sure there are cheaters on high who take advantage of the system, but they are not as easily 'infantalized' as those who are impoverished and helpless. These facts trigger an automatic script, and it leads to the next foundation: Liberty/Oppression.

Liberty/Oppression: the loathing of tyranny

Both Liberals and Conservatives share Liberty/Oppression sensitivies - but their overall moral matrix shapes who is seen as the oppressor. Haidt writes that the Liberty/oppression foundation evolved when small groups banded together to fight alpha males who were overly bullying or tyrannical. He writes that 'anything suggestive of aggressive controlling behavior of an alpha male or female can trigger this form of righteous anger, which is sometimes called reactance.' This is why revolutionaries just feel that murdering 'tyrants' is morally justified. And it's why a brash Trump triggers intense, automatic, unjustified disgust and hatred. Haidt writes:

p.203 said:The hatred of oppression is found on both sides of the political spectrum. The difference seems to be that for liberals—who are more universalistic and who rely more heavily upon the Care/harm foundation—the Liberty/oppression foundation is employed in the service of underdogs, victims, and powerless groups everywhere. It leads liberals (but not others) to sacralize equality, which is then pursued by fighting for civil rights and human rights. Liberals sometimes go beyond equality of rights to pursue equality of outcomes, which cannot be obtained in a capitalist system. This may be why the left usually favors higher taxes on the rich, high levels of services provided to the poor, and sometimes a guaranteed minimum income for everyone.

Conservatives, in contrast, are more parochial—concerned about their groups, rather than all of humanity. For them, the Liberty/oppression foundation and the hatred of tyranny supports many of the tenets of economic conservatism: don’t tread on me (with your liberal nanny state and its high taxes), don’t tread on my business (with your oppressive regulations), and don’t tread on my nation (with your United Nations and your sovereignty-reducing international treaties).

It’s not that human nature suddenly changed and became egalitarian; men still tried to dominate others when they could get away with it. Rather, people armed with weapons and gossip created what Boehm calls “reverse dominance hierarchies” in which the rank and file band together to dominate and restrain would-be alpha males. (It’s uncannily similar to Marx’s dream of the “dictatorship of the proletariat.”) The result is a fragile state of political egalitarianism achieved by cooperation among creatures who are innately predisposed to hierarchical arrangements. It’s a great example of how “innate” refers to the first draft of the mind. The final edition can look quite different, so it’s a mistake to look at today’s hunter-gatherers and say, “See, that’s what human nature really looks like!”

For groups that made this political transition to egalitarianism, there was a quantum leap in the development of moral matrices. People now lived in much denser webs of norms, informal sanctions, and occasionally violent punishments. Those who could navigate this new world skillfully and maintain good reputations were rewarded by gaining the trust, cooperation, and political support of others.

Those sum up the basic Liberal values - the rest belong, theoretically, to more conservative individuals.

Loyalty/Betrayal: standing with your group, family, nation

Haidt exemplifies this ethic with an interesting story about boys who went to an experimental summer camp:

p.159 said:In the summer of 1954, Muzafar Sherif convinced twenty-two sets of working-class parents to let him take their twelve-year-old boys off their hands for three weeks. He brought the boys to a summer camp he had rented in Robbers Cave State Park, Oklahoma. There he conducted one of the most famous studies in social psychology, and one of the richest for understanding the foundations of morality. Sherif brought the boys to the camp in two groups of eleven, on two consecutive days, and housed them in different parts of the park. For the first five days, each group thought it was alone. Even still, they set about marking territory and creating tribal identities.

One group called themselves the “Rattlers,” and the other group took the name “Eagles.” The Rattlers discovered a good swimming hole upstream from the main camp and, after an initial swim, they made a few improvements to the site, such as laying a rock path down to the water. They then claimed the site as their own, as their special hideout, which they visited each day. The Rattlers were disturbed one day to discover paper cups at the site (which in fact they themselves had left behind); they were angry that “outsiders” had used their swimming hole.

A leader emerged in each group by consensus. When the boys were deciding what to do, they all suggested ideas. But when it came time to choose one of those ideas, the leader usually made the choice. Norms, songs, rituals, and distinctive identities began to form in each group (Rattlers are tough and never cry; Eagles never curse). Even though they were there to have fun, and even though they believed they were alone in the woods, each group ended up doing the sorts of things that would have been quite useful if they were about to face a rival group that claimed the same territory. Which they were.

On day 6 of the study, Sherif let the Rattlers get close enough to the baseball field to hear that other boys—the Eagles—were using it, even though the Rattlers had claimed it as their field. The Rattlers begged the camp counselors to let them challenge the Eagles to a baseball game. As he had planned to do from the start, Sherif then arranged a weeklong tournament of sports competitions and camping skills. From that point forward, Sherif says, “performance in all activities which might now become competitive (tent pitching, baseball, etc.) was entered into with more zest and also with more efficiency.” Tribal behavior increased dramatically. Both sides created flags and hung them in contested territory. They destroyed each other’s flags, raided and vandalized each other’s bunks, called each other nasty names, made weapons (socks filled with rocks), and would often have come to blows had the counselors not intervened.

So this moral foundation rests in the need for creating cohesive tribes and figuring out who's a team player - who will go all the way when making sacrifices for the welfare of the group. This entails personal sacrifice and seems to me to be something that could be based more on group-level selection than individual selection (something Haidt writes extensively on in Part 3 of his book).

Authority/Subversion: submitting to tradition and legitimate author

This moral matrix sensitizes us to how people ought to behave in power dynamics. It strikes me as similar to Jordan Peterson's primitive 'lobster' system. That system, running on serotonin, rewards lobsters who rise higher in the hierarchy while those who fall get their serotonin restricted. Influencing the amount of serotonin can even initiate duels between lobsters. In human society this moral foundation sensitizes us to the idea that those in power have the right to be demanding but that they also have the duty to look after the welfare of the group, as well as to submitting to long-standing tradition.

Haidt claims he lifted this foundation directly from the anthropologist Alan Page Fiske's idea of the Authority Ranking relationship. Fiske pioneered Relational Models Theory:

An Authority Ranking relationship is a hierarchy in which individuals or groups are placed in relative higher or lower relations . Those ranked higher have prestige and privilege not enjoyed by those who are lower. Further, the higher typically have some control over the actions of those who are lower. However, the higher also have duties of protection and pastoral care for those beneath them. Metaphors of spatial relation, temporal relation, and magnitude are typically used to distinguish people of different rank. For example, a King having a larger audience room than a Prince, or a King arriving after a Prince for a royal banquet. Further examples include military rankings, the authority of parents over their children especially in more traditional societies, caste systems, and God’s authority over humankind. Brute coercive manipulation is not considered to be Authority Ranking; it is more properly categorized as the Null Relation in which people treat each other in non-social ways.

Sanctity/Degradation: abhorrence for disgusting things, foods, actions

Sanctity refers to what is considered 'untouchable' - things that are potentially contagious and that could decimate the group if spread. According to Haidt it started with the challenge of choosing what to eat - as omnivores people had to decide what was and wasn't food. This led to disgust at things that carried deadly pathogens and onward to things that carried potentially deadly ideas.

Laura said:One wonders, of course, if these "moral foundations" might reflect STS/STO orientations and/or possibilities of OP vs souled types?

Haidt writes that we are 90% primate and 10% hive. That dynamic in and of itself strikes me as resembling a balance of STS/STO traits. And it seems like the Liberal types share less of the STO traits than the Conservative. I'm also struck by how group-oriented the three foundations are that Liberals lack - Authority entails a respect for high and low as well as a value for tradition (what others have accomplished), loyalty is primarily other-centered in the kind of sacrifice made for others over time, and sanctity, when taken to its extreme in religious manifestations, is a yearning to understand God and the mysteries for existence. The Liberal values of care, oppression, and fairness all sound similar to the values of teenagers. Haidt shares evidence that Liberals simply can't understand Conservatives while Conservatives completely understand Liberals - thus making one seem like the adult and the other the child.

Haidt writes:

p.334 said:In a study I did with Jesse Graham and Brian Nosek, we tested how well liberals and conservatives could understand each other. We asked more than two thousand American visitors to fill out the Moral Foundations Questionnaire. One-third of the time they were asked to fill it out normally, answering as themselves. One-third of the time they were asked to fill it out as they think a “typical liberal” would respond. One-third of the time they were asked to fill it out as a “typical conservative” would respond. This design allowed us to examine the stereotypes that each side held about the other. More important, it allowed us to assess how accurate they were by comparing people’s expectations about “typical” partisans to the actual responses from partisans on the left and the right. Who was best able to pretend to be the other?

The results were clear and consistent. Moderates and conservatives were most accurate in their predictions, whether they were pretending to be liberals or conservatives. Liberals were the least accurate, especially those who described themselves as “very liberal.” The biggest errors in the whole study came when liberals answered the Care and Fairness questions while pretending to be conservatives. When faced with questions such as “One of the worst things a person could do is hurt a defenseless animal” or “Justice is the most important requirement for a society,” liberals assumed that conservatives would disagree. If you have a moral matrix built primarily on intuitions about care and fairness (as equality), and you listen to the Reagan narrative, what else could you think? Reagan seems completely unconcerned about the welfare of drug addicts, poor people, and gay people. He’s more interested in fighting wars and telling people how to run their sex lives.

Haidt also wrote that the three moral centers that Liberals lack actually shock them:

Liberal brains showed more surprise, compared to conservative brains, in response to sentences that rejected Care and Fairness concerns. They also showed more surprise in response to sentences that endorsed Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity concerns (for example, “In the teenage years, parental advice should be heeded” versus “… should be questioned”). In other words, when people choose the labels “liberal” or “conservative,” they are not just choosing to endorse different values on questionnaires. Within the first half second after hearing a statement, partisan brains are already reacting differently. These initial flashes of neural activity are the elephant, leaning slightly, which then causes their riders to reason differently, search for different kinds of evidence, and reach different conclusions. Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second.

This is definitely a must-read for understanding what's going on on the political stage. Too bad those who most urgently should read it won't!

The theory that Haidt develops to explain these differences is take from E.O. Wilson's "The Social Conquest of Earth". I just finished this book; not recommending it because it is boring and gets a lot wrong, IMO, because I can easily see the guy is really stretching to fit the facts to evolutionary theory.

Anyway, the basic theory that Haidt more or less adopts is multi-level evolution. That is, an individual may evolve within a group to be selfish to give survival advantages to himself and descendants. But, humanity has long consisted of GROUPS that compete against each other and this is what drives self-less evolution or self-sacrificing behavior: people will sacrifice themselves for their group. Human beings evolve with two conflicting urges: act for the self, or act for the group. The main model for this almost unheard of sociality is that of bees and ants.

There does seem to be some evidence that this is part of the answer, but I don't think it is the whole answer. Haidt and Wilson point out that human groups, unlike bees/ants and one or two other social types, form groups that include NON-kin members. That's pretty much unheard of in evolutionary behavior and pretty much does away with Dawkins' "selfish gene" theory. When you go directly to Wilson to try to understand this, you find that he really can't explain it though he does make a serious effort. It is the last three moral foundations that belong to this group behavior.

What it suggests to me, though certainly Wilson nor Haidt would countenance such an idea, is SPIRITUAL influence. The Cs have said that "networking" is a 4D STO principle. They have said that humans on earth were originally in a network with 4D STO beings until "The Fall". They have also suggested that humans are fragments of a greater soul-type entity. Ra has referred to this as a "social memory COMPLEX". I once asked if the "gods" in mythology weren't symbols of these "higher beings" and that people were inclined to seek out their "soul family" to rejoin. Cs have talking about "connecting chakras". And finally, Gurdjieff talks about the "Esoteric group" as being one that acts as one, so to say.

Taking all this together suggests that the 6 foundation moral system is a consequence of this spiritual influence on humanity, that the evolution of GROUPS isn't so much evolution as an expression of spiritual connections at higher levels. The conflict within the individual isn't so much the conflict of double-mindedness due to evolution on the two tracks, but rather the conflict of the soul vs. the animal based body system.

We have learned a lot, in an esoteric sense, about seeing the unseen in other human beings such as pathological types, and that one cannot give to them because it simply fuels their descent in to service to the self. Ra expresses it as a "war" where the STO elements cannot give in to the demand of the STS elements to submit, otherwise the whole deal would collapse including the STS side which operates due to free will. This seems to be expressed in the human dynamic as well. The most basic level of it is often referred to as "tough love".

Anyway, these are some of the thoughts I've had about this and why I suggested that the 3 foundation moral system of the Liberal left in the US is that of the Organic Portal, while the 6 foundation moral system of the right is more like the STO position which considers others - within a group - as self, so to say.

Obviously, as humans, we don't always get things right when they are stepped down from higher densities, but the group care, loyalty, submitting to the authority of the "group mind", and care for sanctity - higher principles - seem to be reflections of higher density STO influences. Yes, care for the individual is there, but is not the primary focus because, as the Cs say, its not the body but the soul that counts and to be body-centric is to be STS. That seems to describe the left/liberals pretty well.

I hope this thinking out loud is understandable. It is easier to know where I'm going with this if you have read Haidt's book.

Anyway, the basic theory that Haidt more or less adopts is multi-level evolution. That is, an individual may evolve within a group to be selfish to give survival advantages to himself and descendants. But, humanity has long consisted of GROUPS that compete against each other and this is what drives self-less evolution or self-sacrificing behavior: people will sacrifice themselves for their group. Human beings evolve with two conflicting urges: act for the self, or act for the group. The main model for this almost unheard of sociality is that of bees and ants.

There does seem to be some evidence that this is part of the answer, but I don't think it is the whole answer. Haidt and Wilson point out that human groups, unlike bees/ants and one or two other social types, form groups that include NON-kin members. That's pretty much unheard of in evolutionary behavior and pretty much does away with Dawkins' "selfish gene" theory. When you go directly to Wilson to try to understand this, you find that he really can't explain it though he does make a serious effort. It is the last three moral foundations that belong to this group behavior.

What it suggests to me, though certainly Wilson nor Haidt would countenance such an idea, is SPIRITUAL influence. The Cs have said that "networking" is a 4D STO principle. They have said that humans on earth were originally in a network with 4D STO beings until "The Fall". They have also suggested that humans are fragments of a greater soul-type entity. Ra has referred to this as a "social memory COMPLEX". I once asked if the "gods" in mythology weren't symbols of these "higher beings" and that people were inclined to seek out their "soul family" to rejoin. Cs have talking about "connecting chakras". And finally, Gurdjieff talks about the "Esoteric group" as being one that acts as one, so to say.

Taking all this together suggests that the 6 foundation moral system is a consequence of this spiritual influence on humanity, that the evolution of GROUPS isn't so much evolution as an expression of spiritual connections at higher levels. The conflict within the individual isn't so much the conflict of double-mindedness due to evolution on the two tracks, but rather the conflict of the soul vs. the animal based body system.

We have learned a lot, in an esoteric sense, about seeing the unseen in other human beings such as pathological types, and that one cannot give to them because it simply fuels their descent in to service to the self. Ra expresses it as a "war" where the STO elements cannot give in to the demand of the STS elements to submit, otherwise the whole deal would collapse including the STS side which operates due to free will. This seems to be expressed in the human dynamic as well. The most basic level of it is often referred to as "tough love".

Anyway, these are some of the thoughts I've had about this and why I suggested that the 3 foundation moral system of the Liberal left in the US is that of the Organic Portal, while the 6 foundation moral system of the right is more like the STO position which considers others - within a group - as self, so to say.

Obviously, as humans, we don't always get things right when they are stepped down from higher densities, but the group care, loyalty, submitting to the authority of the "group mind", and care for sanctity - higher principles - seem to be reflections of higher density STO influences. Yes, care for the individual is there, but is not the primary focus because, as the Cs say, its not the body but the soul that counts and to be body-centric is to be STS. That seems to describe the left/liberals pretty well.

I hope this thinking out loud is understandable. It is easier to know where I'm going with this if you have read Haidt's book.

There does seem to be some evidence that this is part of the answer, but I don't think it is the whole answer. Haidt and Wilson point out that human groups, unlike bees/ants and one or two other social types, form groups that include NON-kin members. That's pretty much unheard of in evolutionary behavior and pretty much does away with Dawkins' "selfish gene" theory. When you go directly to Wilson to try to understand this, you find that he really can't explain it though he does make a serious effort. It is the last three moral foundations that belong to this group behavior.

It definitely seems like the less people's bonds are influenced by genes (family and nation) or conditional circumstances (football team or low-level religion), the more they are influenced by shared values and ideas. Thinking of the ideas of Paul and the early Christian communities here.

As for OP values = liberal values... I could definitely see it, especially with the vegan thing. It seems to me that these moral tendencies could be adapted to serve the aims of progressive ideals. Sanctity/degradation seems very much like it could relate to healthy eating, and also to reducing environmental damage. In-group preference and obedience to Authority seem the most anti-progressive, but they certainly do exhibit their own in-group preferences in the "no friends to the right, no enemies to the left" ideology. Authoritarianism in general is also well recorded among activists of the left as well as the right. My point on that count is just that, if these moral qualities are the attributes of someone with STO potential, there seems to be a lot of potential for distortion and misuse, pretty much just like all our own inborn circuitry. It does seem important that one integrate as much of one's moral instincts into how one views (and acts in) the world.

It was noticed back in the classical age that there was a clear distinction between the values of the Epicureans and the Stoics. The Epicureans were materialists who believed in no afterlife, that pleasure and pain were the only things work focusing on (increasing the former and reducing the latter). The Stoics on the other hand did believe in divine providence and fate, and that we had a sense of duty to endure its slings and arrows in the service of virtue, which often did include service to the state or community as a whole. This contrasted with the Epicurean tendency to withdraw into communities and isolate themselves from the goings-on of society. It seems like if they were transported into today's world and given this test, you'd probably find the Epicureans on the left and the Stoics on the right.

I'm on the third part of the book and had some thoughts when he described the few major big transitions in evolutionary history, which roughly involved the teaming of several organisms to accomplish a function.

He says: 'Whenever a way is found to suppress free riding so that individual units can cooperate, work as a team, and divide labor, selection at the lower level becomes less important, selection at the higher level becomes more powerful, and that higher-level selection favors the most cohesive superorganisms.'

We might be at the crossroads of another major transition. Reminds me of the concept of connecting chakras and uniting or some might be left behind.

I was thinking that when he gives examples of multilevel selection, his outer reach was still "too low": 'genes within chromosomes within cells within individual organisms within hives, societies, and other groups'. The analogy could be extended to densities and STO vs STS, which obviously he never considers even remotely, at least not openly in this book.

He says: 'Whenever a way is found to suppress free riding so that individual units can cooperate, work as a team, and divide labor, selection at the lower level becomes less important, selection at the higher level becomes more powerful, and that higher-level selection favors the most cohesive superorganisms.'

We might be at the crossroads of another major transition. Reminds me of the concept of connecting chakras and uniting or some might be left behind.

I was thinking that when he gives examples of multilevel selection, his outer reach was still "too low": 'genes within chromosomes within cells within individual organisms within hives, societies, and other groups'. The analogy could be extended to densities and STO vs STS, which obviously he never considers even remotely, at least not openly in this book.

Gaby said:The analogy could be extended to densities and STO vs STS, which obviously he never considers even remotely, at least not openly in this book.

Well, he does touch about "the sacred" and "religion", so saying that he never considers it even remotely is premature. I'll keep on reading.

Overall, it is pretty fascinating.

Gaby said:Gaby said:The analogy could be extended to densities and STO vs STS, which obviously he never considers even remotely, at least not openly in this book.

Well, he does touch about "the sacred" and "religion", so saying that he never considers it even remotely is premature. I'll keep on reading.

Overall, it is pretty fascinating.

His overall idea of "sacred" and "religion" is that it is merely a byproduct of group evolution, fantasies that groups use to support cohesiveness and then later, power mongers used to impose tyranny on the masses.

Trending content

-

Thread 'Coronavirus Pandemic: Apocalypse Now! Or exaggerated scare story?'

- wanderingthomas

Replies: 30K -

-