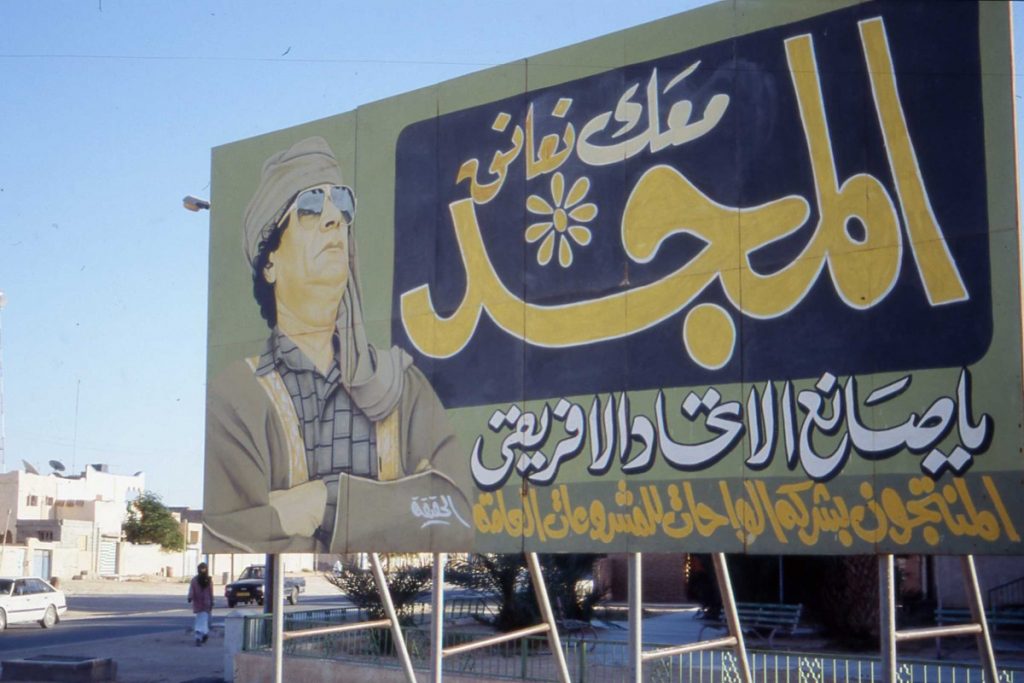

September 1, 2019, marked the

50th anniversary of the Libyan Revolution. Back in 1969, as a young, charismatic army captain, the late Muammar Gaddafi overthrew an ailing, moth-eaten monarch, King Idris Sanussi. The king had managed to survive the post-1952 revolutionary ferment in the Arab world – which spared neither sultan nor imam – leading to popular revolutions in Egypt, Iraq, Yemen and Algeria, as well as left-wing regimes in Syria and Lebanon.

He survived by a deft combination of support from the US (Libya had the world’s largest American airbase, the Wheelus) and the old colonial power, Italy. The military coup in Libya resembled many other ones throughout the Arab world as well as in Latin America, where in the absence of a weak or corrupt Left, it was nationalist – often left-wing – junior military officers who helped in getting rid of unpopular American clients.

Young Gaddafi was immediately christened as his successor by

Gamal Abdel Nasser, the lodestar of the Arab nationalist movement and president of Egypt, who had borne the brunt of American, Israeli, British and French vengeance throughout the 1950s

(the 1952 Anglo-French-Israeli raid on Suez) and 1960s (the 1967 war) because of his popular anti-imperialist programme and support for the Palestinian right of self-determination.

Gaddafi immediately set about undoing in Libya precisely what had made the country a byword for a client state under the Sanussis. The US’s largest airbase, the Wheelus was swiftly dismantled, Italian property, as well as oil multinationals, were nationalised and education and health and housing were decreed free for common Libyans.

Not since the great anti-colonial strategist

Omar Mukhtar – known to his Italian adversaries as the ‘Lion of the Desert’ – had the country seen such a charismatic, unifying figure. Gaddafi, in thrall to his hero Nasser, declared Libya a socialist state and set about achieving the elusive ideal of Arab unity that was to be the undoing of numerous Arabs of his generation at the catastrophic

Arab-Israeli war of 1967, in which the US-backed Israeli army inflicted a decisive defeat on combined Arab armies.

He made himself popular with the Arab masses by espousing the cause of Palestine as well as a champion of national liberation movements around the world, from the Irish Republican Army to the Moros in the Philippines; the Black September revolutionaries who nearly toppled the American-Israeli protectorate of Jordan in 1970 then ruled by the unpopular King Hussein, until reinforcements arrived led by a bloodthirsty Pakistani officer, Brigadier Zia (who just seven years later would go on to brutalise Pakistan for 11 years as its worst military dictator) to restore the status quo, as well as revolutionary Iran and the Polisario Front fighting for an independent homeland in Morocco.

In a region marked by the ascendance of sultans, emirs and colonels who had betrayed the hopes of their people for emancipation by signing up to a peace dictated by the US and Israel, Gaddafi provided a breath of fresh air by not only taking a stand for the beleaguered Palestinians but for international solidarity with national liberation movements, which won him the comradeship of fellow survivors Fidel Castro of Cuba and Nelson Mandela of South Africa.

Obviously, such derring-do long after Nasser was dead and with the Arab nationalist project firmly dead and buried, would not go unpunished. Ronald Reagan punished Gaddafi’s intransigence by attempting to overthrow him via a bombing raid on

Tripoli in 1986, that only succeeded in killing Gaddafi’s infant daughter Hana.

Whatever the international dynamics of Gaddafi’s implication in the Lockerbie disaster of 1988, few of his fellow countrymen actually believed that their leader was involved; they saw it as just another attempt to target their Great Leader.

However, following 9/11, like so many of his fellow politicians across the world, Gaddafi decided to trade battle fatigues for more promising get-rich-quick rewards, and accepted responsibility for Lockerbie, in order to shift his loyalties to the West and to be on the ‘right side of history’. As a result, he was rewarded with swift rehabilitation from rogue leader to a great statesman, meriting visits by Western dignitaries as well as a certain professor Anthony Giddens.

As a result of this about-face, Libya stood to earn $36 billion a year from its oil earnings. Most of these earnings did not reach the people but were used to Dubai and Miami-scape Tripoli, as the next big oil capital of the Arab world. Libya under Gaddafi was well on its way to becoming a family-owned dictatorship, with his son Seif al-Islam the heir-apparent and itching to privatise everything which his father had nationalised in a popular move on coming to power in 1969.

It need not have been like this had Gaddafi listened more keenly to his hero, Nasser, who had once declared in 1970, “I rather like Gaddafi. He reminds me of myself when I was that age.” He would still have been a hero to fellow Libyans as well as thousands of Arabs suffering from moth-eaten dictatorships across the region, as well as to the then newly-minted revolutionaries in Latin America ala Hugo Chavez, Evo Morales, Rafael Correa and Fernando Lugo, whose democratic successes in Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador and Paraguay had helped reverse the neoliberal tide in that continent and made Fidel Castro’s isolated revolution in Cuba relevant again.

But not Muammar Gaddafi. Celebrating the

40th anniversary of the Libyan Revolution back in 2009 as the Great Leader of Libya, he knew that he was now Washington’s favourite dictator in the Arab world after Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and Zine el Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia. He was certainly the last of the generation of Arab nationalists who believed in Arab nationalism as a genuinely progressive ideology and a realistic project, giving hope to millions and freedom from the oppression of pashas, emirs and colonels like himself.

The Great Leader of Libya, the author of the revolutionary text on statecraft,

The Green Book and of 15 other fictional creations, must also surely have known the words of another great leader, St Just, who had said at the time of the French Revolution, as a warning: “Those who make half the revolution dig their own graves.”

Indeed, just two years later, in late 2011, Gaddafi got his first taste of making half the Libyan Revolution when following the Arab Spring uprisings that began from Tunis and Cairo, and then swept towards the Gulf and even the Mashreq, he had to contend with his own people’s discontent at home. Some of us unreconstructed anti-imperialists back then had argued that for all his warts (including delivering a planeload of Sudanese communists to his ally, the Sudanese dictator Jaafar al-Nimeiri back in 1971), it would be very difficult to dislodge him from power from within; the man still had a social base in the country, unlike his counterparts in Tunis, Cairo, Algiers, Sana’a and the Gulf capitals.

And so in order to deflect the infectious enthusiasm across the Arab world, Washington and its allies hastily orchestrated a

NATO bombing campaign against Gaddafi’s Libya. Then, 40,000 bombs, 80,000 dead Libyans and eight months later, Gaddafi’s Libya was brutally destroyed; the sickening spectacle of his grotesque public execution at the hands of NATO-funded rebels later on, providing the nadir in a discourse shamelessly devoid of ‘human rights’, and strongly reeking of oil.

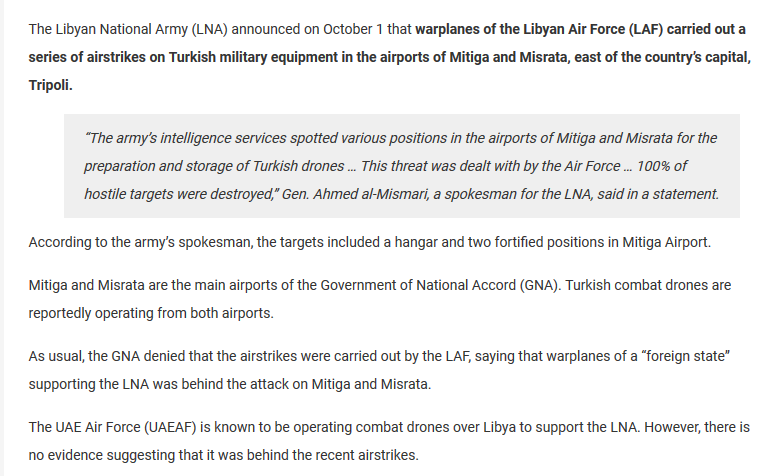

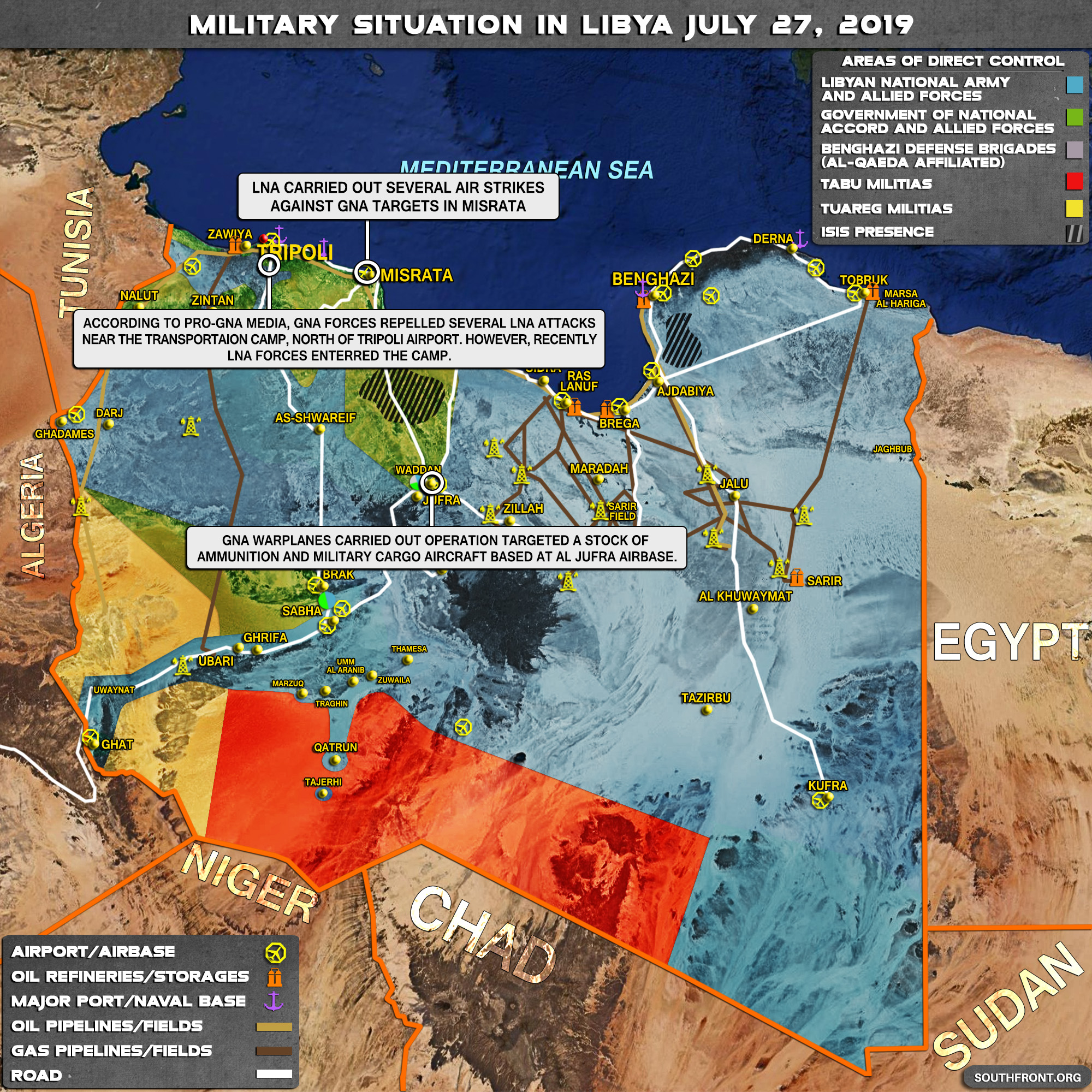

The current state of Libya, effectively divided into two (or three) countries controlled by rival militias and riven by foreign intervention from both Middle Eastern and European powers, no doubt buoyed by the country’s promising oil prospects, is a far cry from what Libya once was, and could have become, had the Libyan Revolution not been derailed and snuffed out rather prematurely, with or without Gaddafi.

Between news of the UN Secretary-General

warning of a full-fledged civil war in the country and dispatches of foreign correspondents more dazzled by the spectacle of the newly-restored

Benghazi port, the most important albeit dispiriting, news from Libya came earlier in this year, when Ahmed Ibrahim al-Faqih, the greatest Libyan writer of the 20th century, passed away in Cairo on April 30 at the age of 76, a few weeks after forces loyal to the Libyan strongman Khalifa Haftar launched an offensive to take the capital Tripoli from the UN-recognised Libyan government in Tripoli.

The news was barely reported; though had Faqih been more fortunate or been born in a European country, he might have been Libya’s first-ever Nobel Laureate. Born in the same year as Gaddafi, Faqih came of age in the heyday of the Arab nationalism of the 1960s, his fiction winning recognition throughout the Arab and international worlds.

His autobiographical trilogy of novels (

I Shall Present You with Another City,

These Are the Borders of My Kingdom and

A Tunnel Lit by a Woman) opens: ‘A time has passed and another time is not coming.’ The final sentence of the trilogy is: ‘A time has passed and another time has not come and will not come.’

One wishes now that Gaddafi – who was a great admirer of Fagih’s 12-volume sequence

Maps of the Soul, where the portrait of the Field Marshal Italo Balbo, the Italian fascist colonial leader of Libya is far more humane and reasonable than the real-life Colonel Gaddafi on which it was based – had paid heed to this wise counsel when he could.

southfront.org

southfront.org