Sacks served as an instructor and later professor of clinical neurology at

Yeshiva University's

Albert Einstein College of Medicine from 1966 to 2007, and also held an appointment at the

New York University School of Medicine from 1992 to 2007. In July 2007 he joined the faculty of

Columbia University Medical Center as a professor of neurology and

psychiatry.At the same time, he was appointed Columbia University's first "Columbia University Artist" at the university's

Morningside Heights campus, recognising the role of his work in bridging the arts and sciences. He was also a visiting professor at the

University of Warwick in the UK. He returned to New York University School of Medicine in 2012, serving as a professor of neurology and consulting neurologist in the school's epilepsy centre.

Sacks's work at Beth Abraham Hospital helped provide the foundation on which the

Institute for Music and Neurologic Function (IMNF) is built; Sacks was an honorary medical advisor.he Institute honored Sacks in 2000 with its first

Music Has Power Award. The IMNF again bestowed a

Music Has Power Award on him in 2006 to commemorate his "40 years at Beth Abraham and honor his outstanding contributions in support of

music therapy and the effect of music on the human brain and mind."

Sacks maintained a busy hospital-based practice in New York City. He accepted a very limited number of private patients, in spite of being in great demand for such consultations. He served on the boards of

The Neurosciences Institute and the

New York Botanical Garden.

Writing

In 1967 Sacks first began to write of his experiences with some of his neurological patients. He burned his first such book,

Ward 23, during an episode of self-doubt. His books have been translated into over 25 languages. In addition, Sacks was a regular contributor to

The New Yorker,

the New York Review of Books,

The New York Times,

London Review of Books and numerous other medical, scientific and general publications. He was awarded the

Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science in 2001.

Sacks's work is featured in a "broader range of media than those of any other contemporary medical author" and in 1990,

The New York Times wrote he "has become a kind of poet laureate of contemporary medicine".

Sacks considered his literary style to have grown out of the tradition of 19th-century "clinical anecdotes", a literary style that included detailed narrative case histories, which he termed novelistic. He also counted among his inspirations the case histories of the Russian neuropsychologist

A. R. Luria, who became a close friend through correspondence from 1973 until Luria's death in 1977. After the publication of his first book

Migraine in 1970, a review by his close friend

W. H. Auden encouraged Sacks to adapt his writing style to "be metaphorical, be mythical, be whatever you need."

Sacks described his cases with a wealth of narrative detail, concentrating on the experiences of the patient (in the case of his

A Leg to Stand On, the patient was himself). The patients he described were often able to adapt to their situation in different ways, although their neurological conditions were usually considered incurable. His book

Awakenings, upon which the 1990

feature film of the same name is based, describes his experiences using the new drug

levodopa on

post-encephalitic patients at the Beth Abraham Hospital, later Beth Abraham Center for Rehabilitation and Nursing, in New York.

Awakenings was also the subject of the first documentary, made in 1974, for the British television series

Discovery. Composer and friend of Sacks

Tobias Picker composed a ballet inspired by

Awakenings for the

Rambert Dance Company, which was premiered by Rambert in

Salford, at

Opera Theatre of Saint Louis.

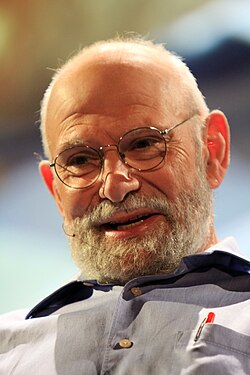

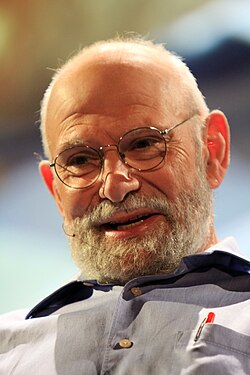

Sacks in 2009

In his memoir

A Leg to Stand On he wrote about the consequences of a near-fatal accident he had at age 41 in 1974, a year after the publication of

Awakenings, when he fell off a cliff and severely injured his left leg while

mountaineering alone above

Hardangerfjord, Norway.

In some of his other books, he describes cases of

Tourette syndrome and various effects of

Parkinson's disease. The title article of

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat describes a man with

visual agnosia and was the subject of a 1986 opera by

Michael Nyman. The book was edited by Kate Edgar, who formed a long-lasting partnership with Sacks, with Sacks later calling her a “mother figure” and saying that he did his best work when she was with him, including

Seeing Voices, Uncle Tungsten, Musicophilia, and Hallucinations.

The title article of his book

An Anthropologist on Mars, which won a

Polk Award for magazine reporting, is about

Temple Grandin, an

autistic professor. He writes in the book's preface that neurological conditions such as autism "can play a paradoxical role, by bringing out latent powers, developments, evolutions, forms of life that might never be seen, or even be imaginable, in their absence". Sacks's 1989 book

Seeing Voices covers a variety of topics in

deaf studies. The romantic drama film

At First Sight (1999) was based on the essay "To See and Not See" in

An Anthropologist on Mars. Sacks also has a small role in the film as a reporter.

In his book

The Island of the Colorblind Sacks wrote about an island where many people have

achromatopsia (total colourblindness, very low visual acuity and high

photophobia). The second section of this book, titled

Cycad Island, describes the

Chamorro people of

Guam, who have a high incidence of a neurodegenerative disease locally known as

lytico-bodig disease (a devastating combination of

ALS,

dementia and

parkinsonism). Later, along with

Paul Alan Cox, Sacks published papers suggesting a possible environmental cause for the disease, namely the toxin

beta-methylamino L-alanine (BMAA) from the

cycad nut accumulating by

biomagnification in the

flying fox bat.

In November 2012 Sacks's book

Hallucinations was published. In it he examined why ordinary people can sometimes experience hallucinations and challenged the stigma associated with the word. He explained: "Hallucinations don't belong wholly to the insane. Much more commonly, they are linked to sensory deprivation, intoxication, illness or injury." He also considers the less well known

Charles Bonnet syndrome, sometimes found in people who have lost their eyesight. The book was described by

Entertainment Weekly as: "Elegant... An absorbing plunge into a mystery of the mind."

He also wrote

The Mind's Eye,

Oaxaca Journal and

On the Move: A Life (his second autobiography).

Before his death in 2015 Sacks founded the Oliver Sacks Foundation, a non-profit organization established to increase understanding of the brain through using narrative non-fiction and case histories, with goals that include publishing some of Sacks's unpublished writings, and making his vast amount of unpublished writings available for scholarly study. The first posthumous book of Sacks's writings,

River of Consciousness, an anthology of his essays, was published in October 2017. Most of the essays had been previously published in various periodicals or in science-essay-anthology books, but were no longer readily obtainable. Sacks specified the order of his essays in

River of Consciousness prior to his death. Some of the essays focus on repressed memories and other tricks the mind plays on itself. Sacks was a prolific handwritten-letter correspondent, and never communicated by e-mail.

.

.