You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Apartment building partially collapses near Miami Beach, rescues underway

- Thread starter daddycat

- Start date

Haven't watched this yet, but came across this previously:This is about a half hour vid theorizing the collapse. A interesting detail is the support columns are smaller in the collapsed part of the building.

[...] bringing the death toll to 22, with 126 still unaccounted for.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis addressed the tragic discovery and also warned of possible dangers to the continuing rescue operation and remaining building by a tropical storm that has now become a category 1 hurricane.

'It is emotionally draining. They were able to identify a child whose father worked for the City of Miami Fire Department and these are tough days,' he said.

'Tropical storm Elsa has now become Hurricane Elsa and I have ordered our Department of Emergency Management to start preparing a potential state of emergency.

'We don't know exactly the track it's going to take. It is possible that we could see tropical force winds as early as Sunday night in southern Florida.

'Our Department of Emergency Management is assuming that will happen and making the necessary preparation to be able to protect a lot of the equipment. You could potentially have an event out at the building as well.'

[...]

The tragic discovery came as rescue efforts resumed after Florida officials temporarily halted operations earlier on Thursday out of fear the remaining tower at the site could cause further collapse.

Surfside Mayor Charles Burkett told NBC News Thursday officials are also considering carrying out a controlled demolition of the part of Champlain Towers South that is still standing ahead of a tropical storm heading to the area.

Burkett said the impending adverse weather was raising further concerns about the structural integrity of the remains of the 12-story tower.

'If the [remaining] building is going to fall, we should make sure it falls the right way,' he said.

Rescue efforts were halted and the area around the building was cleared just after 2am Thursday - almost exactly one week to the minute on from the collapse at 1.25am on June 24.

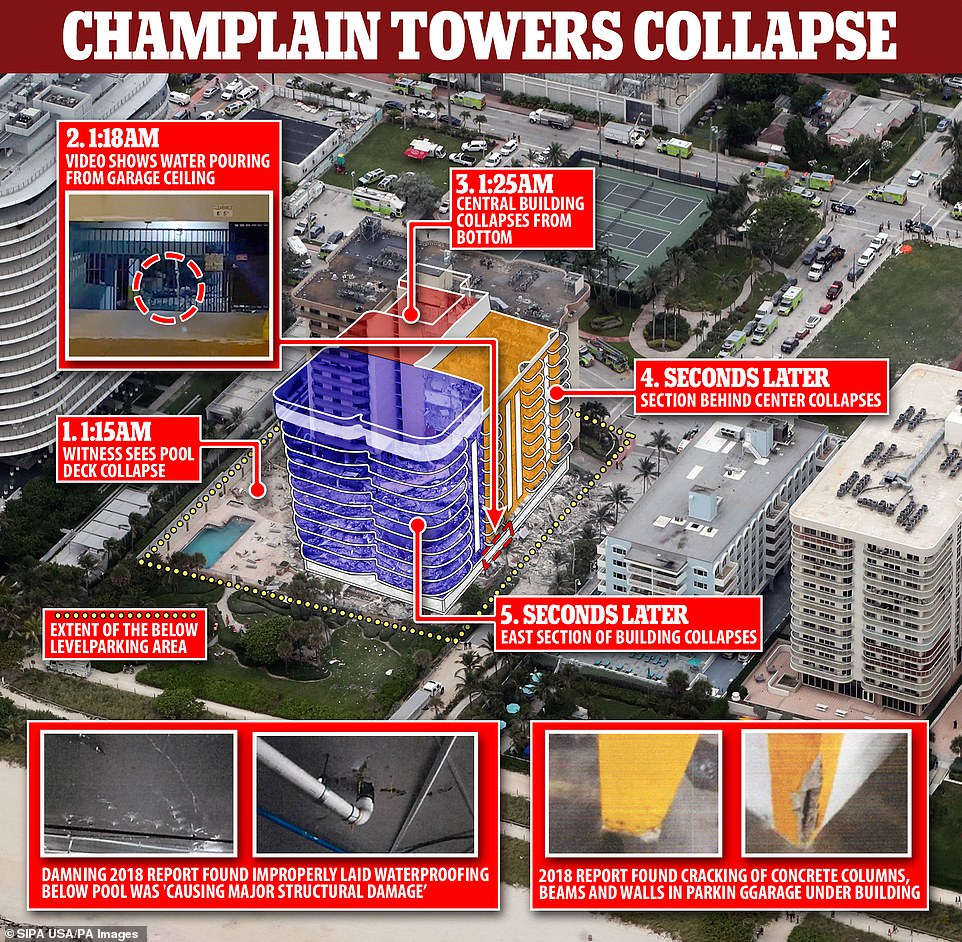

The Champlain Towers South collapse started from the bottom of the central building, with that part of the tower falling from its base down.

Seconds later, the section behind the center collapsed, followed by the east section moments later.

The west section of the building is still standing and has been closely monitored during the search as rescue teams have combed through the rubble round the clock.

A bombshell report released just last fall emerged on Thursday revealing extensive concrete deterioration and corrosion of steel reinforcements had been found at the site of the condo.

The damage had grown so bad that repair work was put on hold over fears that even performing it could endanger the stability of surrounding buildings.

That ominous assessment was carried out in October 2020 by the firm Concrete Protection and Restoration and Morabito Consultants.

It was led by structural engineer Frank Morabito, who both found several issues including a potentially deep deterioration of concrete near the pool area, and who performed prior inspections on the same building as far back as 2018, which yielded similarly worrying results.

But the repair and restoration work 'could not be performed' because the pool 'was to remain in service for the duration of the work' and because bringing in necessary equipment required to conduct the excavation of concrete at the pool 'could affect the stability of the remaining adjacent concrete constructions.'

Although the report may not specifically identify what caused last weeks collapse of the north Miami condo, the documents highlight the state of disrepair the building had been allowed to languish, and may have played some part.

At the very least, issues appear to have been downplayed, ignored or put off from being addressed and rectified.

The report from last October, which was seen by USA Today, was reported to the condo board and building owners in phases rather than comprehensively which may have had the unfortunate affect of obscuring just how serious the problem was.

Buildings in Miami-Dade County need to be recertified every 40 years. Morabito Consultants were hired by the Champlain Tower South Condominium Association to perform an inspection and conduct repairs which were to be completed by this year.

Watched this and here's the mentioned follow up vid [11:57]:This is about a half hour vid theorizing the collapse.

In this vid, the narrator reports that there are fires inside the collapsed building debris! As a huge crane removes chunks, smoke billows out and water has to be poured onto the opening! I don't see how there are going to be any survivors found at this point - it'll be lucky to even find all the remains. Truly heart rending - a memorial is being created along a fence with flowers, notes, and pics of missing.

Interesting that starting with the mention of CNN and Anderson Cooper is a blue and white horizontally striped structure that brings to mind the one on Epstein's island:

It extends quite a ways with a partially exposed name in capital letters - not sure if it's a media structure; from the vid:

Weird. And Anderson Cooper is wearing two masks! He arrived just wearing the white one, but I guess he didn't feel "safe" enough (that's Sanjay Gupta next to him - they found something to chuckle about, imagine that). Perfectly safe to remove both masks to deliver his "live" report though.

There's a stream of police cars going along the street - for what purpose?! Apparently the celebrity media talking heads need police protection - go figure. Huge police and emergency personnel presence. Also, blocking off the beach way beyond the bounds of the affected property - afraid someone will see something they shouldn't? Dogs being brought in for search and rescue and/or recovery.

As of now, potential hurricane Elsa may swing west of the Miami area - otherwise, a lot of packing up will have to happen.

Metrist

The Living Force

The What news WON'T show vid...

That's the first one I watched, and I found the other while looking it up again.

I like them, but the person making them alluded to being an engineer, but if you look at his video list, he's like a ad man, advertising all kinds of tools from Lowes to Home Depot. Maybe a local handyman celebrity?

Anyway, I caught that part where they cordoned off the beach... But then he's allowed so close to all the major media camped around the site....

Anyway, it is more interesting than the news, and his observations seem valid.

That's the first one I watched, and I found the other while looking it up again.

I like them, but the person making them alluded to being an engineer, but if you look at his video list, he's like a ad man, advertising all kinds of tools from Lowes to Home Depot. Maybe a local handyman celebrity?

Anyway, I caught that part where they cordoned off the beach... But then he's allowed so close to all the major media camped around the site....

Anyway, it is more interesting than the news, and his observations seem valid.

BHelmet

The Living Force

DuByne of adapt 2030 makes an interesting Possible connection between the hotel collapse and the weird underwater flaming pipeline Event not Far away as Inner earth change related: being an effect of the earth - sun relationship which is fluxing into the GSM as “the show” starts to get going. California get ready?

I suspect they were curious as to why the concrete cores were vuggy/fractured.Drilling took place up to a foot down in order to determine the structure of the concrete below. The work 'yielded some curious results as it pertained to the structural slab's depth' - but the reason as to why the results were 'curious' was not explained, the report showed

A typical concrete core looks like this:

Metrist

The Living Force

You can see the little rocks in the cement, but the cement in the pictures of the debris looks like cement without rock aggregate. And it's broken up and rounded rather than jagged and rocky. I saw that and wondered if construction was different in Florida - that since they have more sand, that is used for aggregate.A typical concrete core looks like this:

And there is lots of areas where the rebar is striped from the cement - if the concrete had a rocky consistency, it would adhere better to the rebar as the ribs of the rebar act to bind with the cement and rock, but if it were finer material, it might have fatigued over time, and the bond between cement and rebar gave way.

And this might be one of those engineering disasters that span the building industry for that region and time period. And they might not want to address this because of the scale of the problem?

Metrist

The Living Force

I watched a later video by this guy, and he makes a correction about the type of construction, and so at least the pictures reveal the extent of the spalling, but his notion of the type of construction is wrong.Here's another vid with a different focus concerning the concrete slab integrity. It shows pictures from earlier this year of the outside of the building with extensive spalling at the anchor points crucial to the concrete slab integrity. About 20 min.

the appearance of the aggregate can be enhanced by wetting the core, a core left out to dry will appear more like the pics Jeep posted. The pic I provided was likely fresh/wet for the sake of appearance, and wasn't the same type of concrete as the first pics.You can see the little rocks in the cement, but the cement in the pictures of the debris looks like cement without rock aggregate. And it's broken up and rounded rather than jagged and rocky. I saw that and wondered if construction was different in Florida - that since they have more sand, that is used for aggregate.

And there is lots of areas where the rebar is striped from the cement - if the concrete had a rocky consistency, it would adhere better to the rebar as the ribs of the rebar act to bind with the cement and rock, but if it were finer material, it might have fatigued over time, and the bond between cement and rebar gave way.

And this might be one of those engineering disasters that span the building industry for that region and time period. And they might not want to address this because of the scale of the problem?

I'm not a concrete expert but have spent years working for geotechnical engineering companies as a driller...

the point I was trying to make is that there should be a solid core, without voids or breaks.

The fallout and reflections of the human cause of error and erosion.

www.theatlantic.com

JULY 2, 2021

www.theatlantic.com

JULY 2, 2021

Florida Judge Orders Surfside Condo Association Board Into Receivership

Updated July 2, 20216:01 PM ETA Miami-Dade Circuit judge has placed the Champlain Towers South condo association into receivership. Judge Michael Hanzman appointed Michael Goldberg to handle all of the condo association's financial matters while the court hears lawsuits related to the building's collapse.

Five lawsuits have been filed so far, and more claims are expected in the coming months.

Authorities have confirmed the deaths of 22 people and say 126 others remain unaccounted for after the catastrophic collapse of most of the 12-story building on June 24. Miami-Dade County Mayor Daniella Levine Cava said she has signed an order to demolish the remaining part of structure that she will invoke when engineers advise her it should be done.

At a hearing Friday, Hanzman commended the condo association for agreeing to receivership.

"These individuals who are unit owners here and served on the board are in a tremendously difficult time, a tremendously stressful time. And I commend all of them for having the wisdom and the insight to realize it is time to step aside and let an independent party with no stake in the proceedings, either emotionally or financially, step in and take care of business."

A lawyer representing the condo association says the board held a meeting Thursday and voted unanimously to accept receivership. "Every living and accounted for board members was present. There was one board member who remains regrettably unaccounted for as a result of the collapse of the condominium tower."

A lawyer for the condo association told the judge the building's insurance coverage totals $48 million. The judge said the condo's land will also be an asset, which he estimates will add between $30 million and $50 million to the fund.

The judge instructed the receiver to make arrangements immediately to authorize payments to those directly affected by the building collapse. He instructed the receiver to provide payments up to $10,000 to families of the missing or deceased or to those residents who need housing assistance. And he said $2,000 payments should be made available to families dealing with end-of-life (funeral) costs. Those payments would be an advance on the total recovery that will be available to all parties directly affected by the collapse.

The judge took a firm tone with attorneys, telling them they should consider their role in the case "a public service" and that he wanted to "avoid as much litigation and contention as possible."

He said he wants the case wrapped up within 12 months.

Condo Buildings Are at Risk. So Is All Real Estate.

The disaster in Surfside, Florida, focuses attention on condominiums’ flaws, but all forms of property ownership carry the potential for ugly surprises.

After most of a condominium tower in Surfside, Florida, collapsed last week, the second-guessing began almost immediately. Some residents accused the building’s condominium association of acting too slowly to address known structural flaws identified in a 2018 engineering report. Recent news stories have emphasized dissension among the owners. As someone who studies condos—their history, architecture, politics, and social dynamics, in Florida and all over the United States—I, too, have been wondering whether the building’s divided ownership contributed to the June 24 catastrophe, which killed at least 18 people and left more than 140 missing. Could a single landlord have responded better to engineers’ and occupants’ concerns than an association of 136 homeowners?

Condos have long been big business and a way of life in southeast Florida, which by the 1970s had become America’s center of condo living. Today roughly one in five homeowners in U.S. cities and suburbs lives in a multifamily complex rather than a single-family house, according to U.S. census figures; in Miami and Fort Lauderdale, that share rises to one in three. Surfside residents described Champlain Towers South as a genuine community: “There was a beautiful mixture of cultures and people in that building,” one local told The Wall Street Journal. “People from South America, Cuban Jews, American Jews, American nationals.”

In most ways, the tower in Surfside was no different from Florida’s thousands of other high-rise condo buildings. Those, meanwhile, face many of the same risks—most notably their proximity to the ocean during a time of sea-level rise—as single-owner apartment buildings and other concrete-and-steel properties along the Florida coast. A number of reports suggest that the Champlain Towers South Condominium Association functioned properly and had moved methodically, albeit amid considerable resistance, to figure out how to fix the problems that an engineer had identified.

Investigators still have much to learn about the causes of the disaster. The vagaries of the condo format, including the need to raise $15 million for repairs through a “special assessment” on the owners, might conceivably have slowed the building’s response to structural problems. Absentee ownership, common in many condo buildings, especially in resorts and cosmopolitan business centers, might have hindered repairs further.

Derek Thompson: Why Manhattan’s skyscrapers are empty

And yet the collapse might also have been caused by other, yet-to-be-identified factors that didn’t turn up in the 2018 engineer’s report. “From what I see, [that report] didn’t look like something that I would say, ‘Get the people out,’” Norma Jean Mattei, a University of New Orleans engineering professor, told The Washington Post. “The deterioration played a part, but it wasn’t what caused this failure. Something else had to push this building over the top.” In other words, Champlain Towers South might have suffered not from bad ownership or bad governance but from bad circumstances and bad luck.

Because of the disaster in Surfside, long-standing questions about condo-mania in Florida and elsewhere are resurfacing. The condo, like other forms of co-owned housing such as the co-op, occupies an ambiguous place in American life. Most American homebuyers have historically preferred single-family houses and understood other kinds of dwellings to be second-best. Geographers, sociologists, anthropologists, and political scientists have argued for decades that the condo system is fundamentally unworkable, little more than a scheme cooked up by developers to seduce property buyers with good locations, luxury amenities, and hollow promises of community. Others saw condominium arrangements as an inevitable fiasco, worrying that an amateur group of owners couldn’t possibly run a building competently.

Still, the individually owned apartment emerged in the 19th century in cities such as New York and Washington, D.C., for those who could afford a house but didn’t need or want one—with careful efforts in design and marketing to distinguish them from working-class tenements. The originator of the for-sale apartment in the U.S. in the 1880s opted for a simple system: the corporate-title “cooperative,” in which the association holds title to the entire complex and individual ownership is conveyed by perpetual, in many cases $1-a-year, “proprietary” leases. In some respects, this is a superior model. The single title enables associations to more easily take out commercial loans for repairs, while the leases allow them to evict owners who become a liability.

Yet the power of the association, especially to screen resales, made mortgage lenders wary. And in a nation deeply committed to unfettered property ownership, it also limited the appeal of owning an apartment. Starting in the late 1950s, the mortgage industry, anticipating untapped demand, began to promote condominium arrangements in Florida, then nationally. As early as 1921, Congress questioned the entire premise of for-sale apartments, grilling homeowners about its viability. By 1974, an aggrieved owner, also testifying before Congress, asked, “Can a condominium actually work?” More recently, dysfunctional condo politics have been the stuff of TV comedy on shows such as Seinfeld. Since 2009, disputes between owners and homeowner associations have aired on Sunday mornings in South Florida on an AM radio show called “Condo Craze & HOAs,” hosted by the attorney Eric M. Glazer—a Judge Judy for the Condominium Coast.

Behind much of the skepticism of the condo system were tensions between private rights in property and community obligations. Between the 1880s and World War I, co-owned buildings in the United States were mostly sponsored directly by future tenants (foreshadowing the recent wave of baugruppen in Berlin). By the 1920s, though, speculative developers came to dominate. To sell apartments, they learned to emphasize lifestyle, including ease of physical maintenance (“no lawn to mow,” read many an ad), while downplaying responsibilities.

But owning an apartment, like any other property, comes with its own burdens—just ones less tangible than a lawn. No matter the system, ownership turns tenants, ready or not, into landlords: Members of a condominium automatically become co-owners of a corporate entity responsible for common elements. As nearly everyone who has ever owned an apartment in a large building knows, however, rare is the condo owner who’s attuned to this duty, and rarer still is the one who attends association meetings, let alone serves on the board of directors.

Read: The hot new Millennial housing trend is a repeat of the Middle Ages

And yet developers and sales agents recognized this gap early on. While honing their marketing strategies, they began to encourage buildings to hire “professional” management, leaving associations with few direct responsibilities. Governance could still be challenging. In co-ops in New York and D.C., where associations typically screen new buyers (ostensibly for reasons of financial security), battles erupted over whether to allow resales to Jewish people and, later, single women, Black people, and gay men. In more recent decades, residents of condo buildings have feuded over everything from cosmetic upgrades (redecorating lobbies) to the installation of EV charging stations. These disputes hint at why some early critics believed that condos would inevitably result in huge problems, including premature physical decay.

These predictions occasionally proved true—but almost never in the U.S. In America, our faith in a stable and transparent real-estate system supersedes our deep-seated aversion to public oversight of private transactions. As a result, regulation of condominium-like arrangements in this country, even in freewheeling Florida, has been among the most robust in the world, making American condo owners the envy of their counterparts in places as diverse as Australia, China, and Israel.

People around the world following the news from Surfside are now aware of Miami-Dade County’s requirement that buildings undergo recertification by engineers or architects after 40 years. But since the 1970s, Florida has also introduced an array of other regulations to ensure safe, equitable, and relatively efficient governance of co-owned apartments, and other states have followed its lead in many ways.

When developers experimented with locking associations into management contracts at uncompetitive rates (as detailed in John D. MacDonald’s 1977 disaster novel, Condominium), kept down sales prices by retaining ownership of common areas and renting them back to associations (also at inflated rates), or made monthly charges unsustainably low by retaining control over associations until an overwhelming majority of units were sold, the state outlawed these practices. To allow for a more timely and cost-effective resolution of disputes among owners, and between owners and associations, it set up provisions for resolving disputes outside the courts.

None of this guarantees that, when major repairs become necessary, owners will be able to make decisions or raise money quickly. And even if states push associations harder to take the unique pitfalls of condo arrangements into account, owners are still exposed to other risks, including, in some cases, the uncertainties inherent to waterfront living amid climate change. Ultimately, the condo format could turn out to be a factor in the Surfside disaster, but any presumption of guilt now may provide false reassurance to people who have a stake in other forms of real estate—and face the ugly, rare, and sometimes catastrophic surprises that are a possibility in property ownership of every kind.

Matthew Gordon Lasner is the author of High Life: Condo Living in the Suburban Century. He teaches urban studies and planning at Hunter College.

Hmm whenever the Israelis get involved things get suspicious. Could be be structural integrity issues combined with the crust moving. But there seems to be some fishy elements. Did anyone see this?? Don't know if this info about McAfee and connection to the condo is real:

Tweet sparks conspiracy theory linking John McAfee to condo collapse

A boom then the ground shook...sounds like the towers in 911

Miami condo collapse: A boom, then the ground shook

And a bitchute video of the collapse:

Florida Condo Demolition - McAfee Dead Man Switch Secured

Tweet sparks conspiracy theory linking John McAfee to condo collapse

A boom then the ground shook...sounds like the towers in 911

Miami condo collapse: A boom, then the ground shook

And a bitchute video of the collapse:

Florida Condo Demolition - McAfee Dead Man Switch Secured

Metrist

The Living Force

I saw this one video where a building engineer commented on the debris pile, and he asked: where is all the rebar? There should be a lot, but all there is is rubble. So that's one thing.

And when you see how the concrete disintegrated into small chunks - it reminds me of safety glass, like on car windows when it shatters. So, I'm thinking of the time period, and I remember that crushed rock was like a innovation when I was young: our street we lived on was a crushed rock and tar mixture. Lots of driveways were just crushed rock. I think there was a name for this type of surfacing, but I don't remember... And lots of commercial buildings were decorated with crushed rock - so it was for a time a popular material.

And in looking at the rubble, I can't make out the texture very well, but in some shots it looks like concrete/crushed rock. So, what's the problem? Concrete I've seen nowadays is like cement mixed with rounded rocks - natural rock with smooth surfaces. This would have the best integrity as it doesn't introduce edges in the set concrete, where it would cause disintegration after a determined amount of stress - and shatter like safety glass, as mentioned.

So, the constitution of the concrete flooring is tough up to a threshold, then it disintegrates. If it were rounded rocks, the fracturing would be minimized and spalling would migrate towards the surfaces rather than through weaknesses created by the crushed rocks angularity, and could be repaired with their repair methods. But with the crushed rock, the repairs would only be cosmetic, as it is compromised - and like a cracked window, the crack continues to grow and its integrity weakens.

So, that's my concern. It may have been industry wide for a time to build with such materials, and that it was later recognized and remedied with revised practices, but the fallout remains, and that a lot of buildings might be irreparable and past their time.

And when you see how the concrete disintegrated into small chunks - it reminds me of safety glass, like on car windows when it shatters. So, I'm thinking of the time period, and I remember that crushed rock was like a innovation when I was young: our street we lived on was a crushed rock and tar mixture. Lots of driveways were just crushed rock. I think there was a name for this type of surfacing, but I don't remember... And lots of commercial buildings were decorated with crushed rock - so it was for a time a popular material.

And in looking at the rubble, I can't make out the texture very well, but in some shots it looks like concrete/crushed rock. So, what's the problem? Concrete I've seen nowadays is like cement mixed with rounded rocks - natural rock with smooth surfaces. This would have the best integrity as it doesn't introduce edges in the set concrete, where it would cause disintegration after a determined amount of stress - and shatter like safety glass, as mentioned.

So, the constitution of the concrete flooring is tough up to a threshold, then it disintegrates. If it were rounded rocks, the fracturing would be minimized and spalling would migrate towards the surfaces rather than through weaknesses created by the crushed rocks angularity, and could be repaired with their repair methods. But with the crushed rock, the repairs would only be cosmetic, as it is compromised - and like a cracked window, the crack continues to grow and its integrity weakens.

So, that's my concern. It may have been industry wide for a time to build with such materials, and that it was later recognized and remedied with revised practices, but the fallout remains, and that a lot of buildings might be irreparable and past their time.

Trending content

-

-

Thread 'Coronavirus Pandemic: Apocalypse Now! Or exaggerated scare story?'

- wanderingthomas

Replies: 30K -

-