In African countries they used this method to give vaccines to children. It looks so innocent, just a little drop and voilà! So now the same method for kids, because we know kids are afraid of injections, for reason, and mothers also. Just a drop, like eyes drops, no danger at all and the kid will not cry or make tantrums, with reason. Voilà!I am sure this is just a coincidence, ya know.

Probably nothing to do with the ongoing fear mongering and totalitarian kidnapping and bribing to jab younger and younger kids with as many clot shots as possible.

FDA NEWS RELEASE

FDA Approves First Oral Blood Thinning Medication for Children

Today,(June 21, 2021) the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate) oral pellets to treat children 3 months to less than 12 years old with venous thromboembolism (a condition where blood clots form in the veins) directly after they have been treated with a blood thinner given by injection for at least five days. The FDA also approved Pradaxa oral pellets to prevent recurrent clots among patients 3 months to less than 12 years old who completed treatment for their first venous thromboembolism.

In addition, Pradaxa was approved in capsule form to treat blood clots in patients eight years and older with venous thromboembolism directly after they have been treated with a blood thinner given by injection for at least five days, and to prevent recurrent clots in patients eight years and older who completed treatment for their first venous thromboembolism.[...]

FDA Approves First Oral Blood Thinning Medication for Children

Today, the FDA approved Pradaxa oral pellets and capsules for the treatment and prevention of blood clots in children.www.fda.gov

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Coronavirus Pandemic: Apocalypse Now! Or exaggerated scare story?

- Thread starter wanderingthomas

- Start date

michaelrc

Dagobah Resident

Thank you for posting this, ho ha ha ha. For a second l was I was 16 again. Ho ha ha ha, loved it.

artofdream

Jedi

I was expecting that NewTechMedicine to be eagerly provided and pushed onto the vaccinated. I am also expecting that the old school medicine to become, for obscure and unverifiable reasons, ‘out of stock’.

I hope there are lots of angry lawyers around and lots of people that still read and apply their minds.

For information: Sotrovimab - Wikipedia

Sotrovimab is an investigational human neutralizing dual-action monoclonal antibody with activity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, known as SARS-CoV-2.[2][3] It is under development by GlaxoSmithKline and Vir Biotechnology, Inc.[2][4] Sotrovimab is designed to attach to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2.

From the original post from @XPan (Coronavirus Pandemic: Apocalypse Now! Or exaggerated scare story?) on Sotrovimab, did some research (timeline):

- 2021/05/21: Europe - EUA Authorized EMA issues advice on use of sotrovimab (VIR-7831) for treating COVID-19 - European Medicines Agency

- 2021/05/21: Australia - TGA Evaluation (on-going) TGA evaluating first monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID-19, SOTROVIMAB - GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd

- 2021/05/26: USA - EUA Authorized

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Additional Monoclonal Antibody for Treatment of COVID-19

The FDA issued an EUA for an investigational monoclonal antibody therapy for treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in adult and pediatric patients.www.fda.gov

- 2021/08/07: Italy - Official recognition as Treatment Modifiche Registro - anticorpi monoclonali COVID-19

- vaccines

- monoclonal antibody based medicine (Sotrovimab)

- legal impact on health passes which more often than not mainly rely on (push for) vaccination.

- Vaccines EUA, which main criteria of validity rely on the absence of other existing treatment.

- In the US, could be a valid point for Vaccines EUA dismissal

- In Europe, might be more complex in regard to Vaccines EUA dismissal

- Health pass: would depend on national legislations but would be better to address vaccines EUA validity first...

NB. have to take into consideration that all of these are under EUA, and Sotrovimab specifically is to be used for symptomatic patients.

Would rather see other prophylactic treatments (ivermectin, …) officially recognized.

In all cases, wait & see.

Hi_Henry

The Living Force

A letter from a Irish doctor,

Same doctor about vaccination of young.

Letter: Open letter to the Minister for Health

By Contributor 20th July 2021

Blocking of use of Ivermectin

Dear Mr Donnelly;

It is now quite clear that there is a worrying and somewhat sinister attempt to block the use of Ivermectin in the prevention or treatment of SARS-CoV2 infections. This despite numerous randomised control trials,observational trials and case studies. The arguments against use include lack of evidence, clearly this isn’t the case and the safety profile. This drug is 50 years old and has resulted in approximately 20 deaths in that time. Aspirin has killed multiples of this number.

Given that much of the evidence has been in existence for at least one year, and more has subsequently emerged, I would assert that the writers of the ICGP guidelines (April 2020) and the subsequent HIQA guidelines (January 2021) are guilty of the crime of wilful blindness as defined: “The doctrine of willful blindness imputes knowledge to an accused whose suspicion is aroused to the point where he or she sees the need for further inquiries, but deliberately chooses not to make those inquiries.”

As are those who were party to sanctioning such documents. The instructions in these documents advised GPs to basically do nothing in the initial phases, except perhaps have a PCR test to confirm infection, most were not seen by their family doctors, and if they worsened were sent to hospital.

Sadly, many of those in nursing homes were not offered a hospital admission, instead were given oxygen, morphine and midazolam whilst awaiting death.

In all these cases a window of opportunity in the early stages of this condition was lost.

No doubt some of these people would have worsened and died anyway but we will never know how many could have survived because, in the main, GPs did nothing.

Yours Sincerely,

Dr William Ralph, MICGP,

The Ballagh HC,

Enniscorthy,

Wexford.

Same doctor about vaccination of young.

Letter: Sars-CoV2

By Contributor 16th August 2021

Vaccinations of the young

Dear Editor,

Mark Hilliard’s Covid Q+A in the Irish Times (27/7/21) contains a very interesting number, i.e. the risk to the young (those under 25 years) of death from a Sars-CoV2 infection is one in 2-3 million.

That should be reassuring enough for any young person to answer the question ‘do I need this vaccine?’

The risk of facial palsy from mRNA vaccines is one in 5,000, the risk of clots is approximately one in 50,000, of which some will die. The trial size for Pfizer and Moderna at just over 2,000 will not pick this up and the time-frame of monitoring is too short; it is usually two years post-treatment.

The actual recording of post-vaccination adverse events, which is usually mandated as part of the FDA’s Emergency Use Authorisations (EUAs) was conveniently removed from the Pfizer and Moderna products EUAs.

Vaccinating the young and exposing them to a substantially greater risk than the said illness in order to protect a cohort of the population who are already vaccinated makes no sense to me as a practising doctor of 27 years’ experience.

Maybe if I was a shareholder in one of these large pharmaceutical companies I could gladly embraced this warped logic.

Yours Sincerely

Dr William Ralph

MCRN 18288, MICGP

The Ballagh HC

Enniscorthy,

Wexford.

XPan

The Living Force

@XPan, isn't there any option available (like a button, maybe?) about how publish a video and make it available to Embed code? All I can do is to share how it looks when Embed is made available by the account, just under the video on the right:

View attachment 48533

Here is the link: Vérifiez par vous-même. (Liens en description)

Unfortunately, I cannot recover the code from "Inspect" option on the page, as it is the Rumble host page (same goes four YouTube and others).

If anyone here could help with this, it would be much appreciated, thanks!

Edit: Added bolded part of your post and yes, I do think that it could be why there is no Embed option availble. Are you able to modify it?

I believe, I have figured it out, MK Scarlett

It is like I suspected yesterday, that when one uploads a video four options are given how to publish the video, where I first had chosen "personal use" - but that option does not allow me to modify any setting for adding an "embed" button, nor is the content even searchable at Rumble. (The "embed code" info was only available to me in private, when I logged into my Rumble account).

Last edited:

Ocean

The Living Force

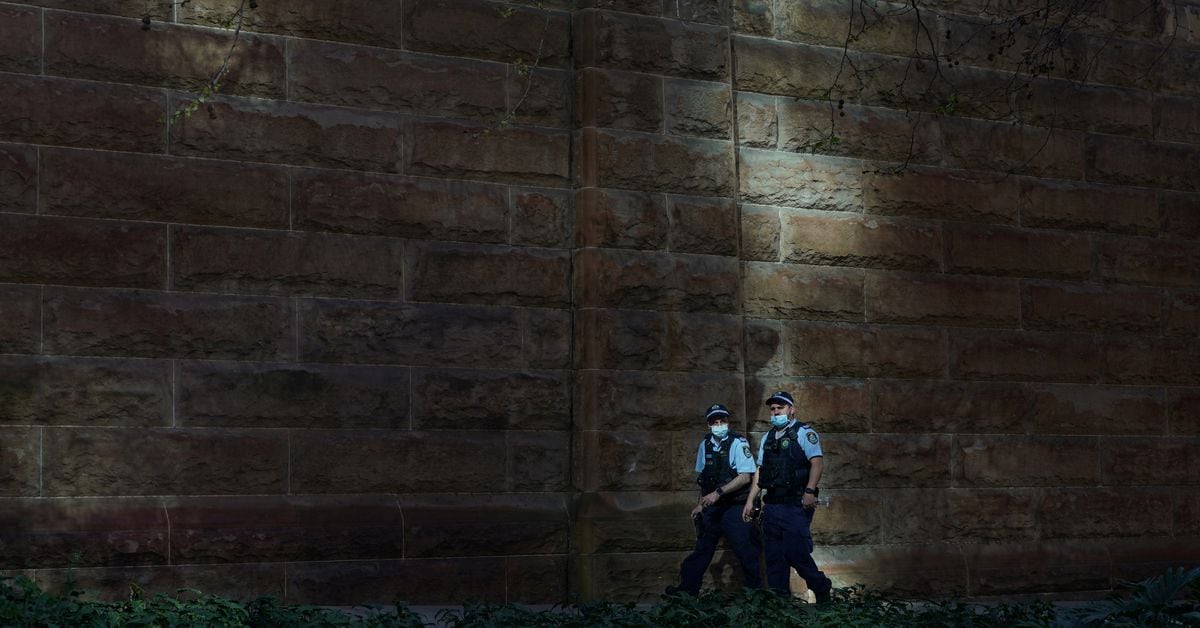

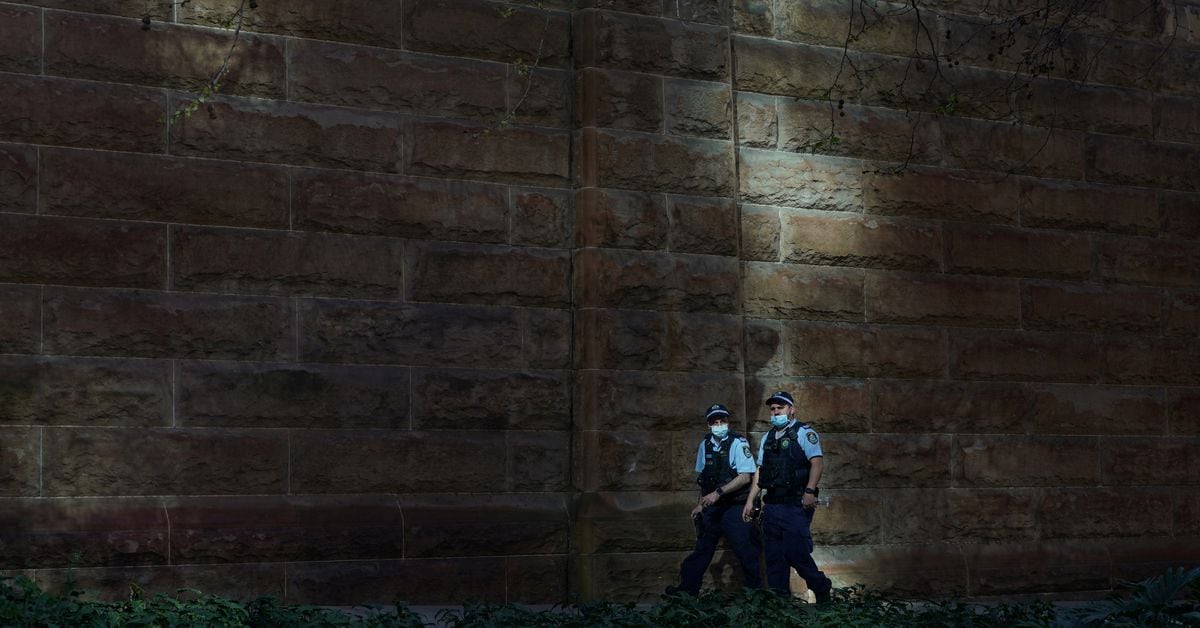

Aussies fighting back. More than 4,000 protestors

www.reuters.com

www.reuters.com

MELBOURNE, Aug 21 (Reuters) - Australian police arrested hundreds of anti-lockdown protesters in Melbourne and Sydney on Saturday and seven officers were hospitalised as a result of clashes, as the country saw its highest ever single-day rise in COVID-19 cases.

Mounted police used pepper spray in Melbourne to break up crowds of more than 4,000 surging toward police lines, while smaller groups of protesters were prevented from congregating in Sydney by a large contingent of riot police.

Victoria state police said that they arrested 218 people in the state capital Melbourne. They issued 236 fines and kept three people in custody for assaulting police. The arrested people face fines of A$5,452 ($3,900) each for breaching public health orders.

Police in New South Wales, where Sydney is the capital, said they charged 47 people with breaching public health orders or resisting arrest, among other offences, and issued more than 260 fines ranging from A$50 ($35) to $3,000. The police said about 250 people made it to the city for the protest.

Sydney, Australia's biggest city with more than 5 million people, has been in a strict lockdown for more than two months, failing to contain an outbreak that has spread across internal borders and as far as neighbouring New Zealand.

Police arrest hundreds of protesters as Australia reports record COVID-19 cases

Police arrest hundreds of protesters as Australia reports record COVID-19 cases

Australian police arrested hundreds of anti-lockdown protesters in Melbourne and Sydney on Saturday and seven officers were hospitalised as a result of clashes, as the country saw its highest ever single-day rise in COVID-19 cases.

MELBOURNE, Aug 21 (Reuters) - Australian police arrested hundreds of anti-lockdown protesters in Melbourne and Sydney on Saturday and seven officers were hospitalised as a result of clashes, as the country saw its highest ever single-day rise in COVID-19 cases.

Mounted police used pepper spray in Melbourne to break up crowds of more than 4,000 surging toward police lines, while smaller groups of protesters were prevented from congregating in Sydney by a large contingent of riot police.

Victoria state police said that they arrested 218 people in the state capital Melbourne. They issued 236 fines and kept three people in custody for assaulting police. The arrested people face fines of A$5,452 ($3,900) each for breaching public health orders.

Police in New South Wales, where Sydney is the capital, said they charged 47 people with breaching public health orders or resisting arrest, among other offences, and issued more than 260 fines ranging from A$50 ($35) to $3,000. The police said about 250 people made it to the city for the protest.

Sydney, Australia's biggest city with more than 5 million people, has been in a strict lockdown for more than two months, failing to contain an outbreak that has spread across internal borders and as far as neighbouring New Zealand.

XPan

The Living Force

The re-uploaded the interview at my Rumble Account, but now with "embed" code available, but the link is new.

COVID Vaccines May Bring Avalanche of Neurological Disease

1h 23 min • English

I did the same with another video link I had referred to in the forum (German doctors looking into the blood of freshly vaccinated people, making astonishing finds) It is an in german held video, also with a "embed" code button under a new link.

Presented By Independent Researches, Lawyers & Doctor

17 min • in german (english subtitles)

PS:

I apologize for the confusion and my ignorance about things like publishing and management on digital platforms and stuff like that, which I am totally new to. It creates kind of unnecessary noise, which really wasn't my intend. Ralf.

Report: FDA to Give Pfizer COVID Vaccine Full Approval Monday

KPIX CBS SF Bay Area

www.sfchronicle.com

Updated: Aug. 22, 2021 6:40 a.m.

www.sfchronicle.com

Updated: Aug. 22, 2021 6:40 a.m.

Full approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration of the Pfizer coronavirus vaccine is expected soon, according to reports. Andrea Nakano reports. (8-20-21)

These 3 communities have some of the lowest vaccination rates in the Bay Area. Why?

As the delta variant fuels a new wave of infections, The Chronicle visited three ZIP...

Glenn Webb took a break from his job picking up trash in the parking lot of a retail strip in Antioch and walked over to a group of public health volunteers offering COVID-19 vaccines out of a minivan.

The QuikStop parking lot in Antioch’s Sycamore neighborhood was bustling on this weekday in July. Shoppers dipped in and out of the

Webb, 58, wasn’t sure he’d get vaccinated, but volunteer nurses had finally persuaded him to sit down in a folding chair and roll up his sleeve. “It’s convenient,” he shrugged.

And that was the point. Antioch neighborhoods have some of the lowest vaccination rates in the Bay Area, communities that have also withstood disproportionately high rates of job loss, eviction and coronavirus infections.

As the delta variant fuels a new wave of infections, The Chronicle visited three ZIP codes with the lowest vaccination rates in the Bay Area to learn why fewer residents there are getting shots and what public health agencies and others are doing about it.

The communities were west Antioch in northeast Contra Costa County, San Francisco’s tiny Treasure Island and a southeastern section of East Oakland that includes flatlands and hills. Their rates for full vaccination are well below their respective counties and, according to state data, under California’s rate of 65% of those 12 and over.

Each place is unique, as are the reasons behind individual choices to delay getting a vaccine. Many unvaccinated residents shared a distrust in the government and medical establishment and a desire not to be rushed or forced into getting the vaccine. Some repeated misinformation about the vaccine that they saw on social media, read on the internet or heard from a friend or family member.

Others were simply unsure how or whether to make the vaccine a priority in their busy lives. A grocery store employee said she worked double shifts six days a week and hadn’t found the time to get a shot until a mobile vaccine van parked outside her workplace.

The Chronicle also witnessed public health employees and volunteers working creatively to get more shots in arms. The effort in Antioch, where a local city council member was on hand to help coax vaccine resisters, showed how far officials are willing to go.

The team had worked in that parking lot off and on throughout the summer, but before setting up there, public health workers sought permission from a man who held court there from his car. He wasn’t officially connected to the shopping center but appeared to have authority over what took place in the parking lot — legal or otherwise.

“We don’t want them to chase us out for not being part of the community,” said Ernesto De La Torre, who manages Contra Costa County’s vaccine ambassador program. “It’s a small tight-knit community. ... We’re just there to get people vaccinated and leave.”

Keith Gonzales thinks about the word “fear.” The 45-year-old Treasure Island resident doesn’t like using it to describe how he feels about the coronavirus vaccine, but it’s close.

“I’m real leery,” Gonzales says, smoking a cigarette outside his low-slung apartment on the San Francisco island, where just 45% of eligible residents are fully vaccinated, according to state vaccination data. “It trips me out that they came up with the vaccine real quick.”

To the scientists who created the vaccines, he asks: “Did you have it on standby? Did you know this was coming?”

If he wants a job — and he does — he’ll need the vaccine. He knows that. But the conspiracy videos he watches stoke his concerns. Like the one with the woman who claims to be a vaccinated nurse, then removes her mask to reveal a disfigured face.

“She said she never had anything wrong before she got the vaccine,” Gonzales says.

Health Services ambassador Diana Aleman (right) offers vaccination information to shoppers at Cielo Market in Antioch. Scott Strazzante / The Chronicle

City health officials set up 11 vaccination sites on the island on March 27. By June 6, they were gone.

In San Francisco, 79% of those 12 and up are fully vaccinated. But it’s not enough. In San Francisco, new cases average 235 a week — up from 27 in early July.

The city’s Department of Public Health says it’s “laser-focused on ramping up vaccine opportunities in hard-hit neighborhoods.”

Treasure Islanders, however, must leave the island for a vaccine.

As of Aug. 3, just 1,258 of them were fully vaccinated. That’s 44%, says the state, which uses census data to conclude there are 2,859 eligible residents. But the island’s five housing providers say there are closer to 2,000 eligible residents, or about 63% vaccinated, said Robert Beck, director of the city’s Treasure Island Development Authority.

Either way, it’s not hard to find the unvaccinated. There are 740 or 1,439 of them, depending on whom you ask.

“I don’t want to be a guinea pig,” said Kurt Shuptrine, 55, who rents storage on the island but lacks a home.

Jin Sheng Wu, 62, walking his grandson in a stroller on Gateview Avenue recently, said he had no time to get vaccinated. His son-in-law, Ben Luo, said the family also worried about subjecting Wu to the vaccine’s potential flu-like symptoms.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls the COVID-19 vaccines safe and effective and suggests people get them right away. COVID-19 has killed 4.4 million people around the world, including 628,000 people in the U.S.

Gonzales admitted that he doesn’t believe his conspiracy videos and said he trusts his doctor, who wants him vaccinated.

So why not get vaccinated, like, now?

“I don’t know,” he said. “I don’t feel like it.”

Mary Johnson leaves her East Oakland home in the mornings only to run errands. That’s because the nearby corner store is still empty before the after-work rush of customers.

For 56-year-old Johnson, the fewer people the better. She is not vaccinated against the coronavirus and isn’t planning to get the shot anytime soon, even though studies show that vaccines are safe and effective against death and hospitalization from COVID-19.

“It’s really rushed,” Johnson said of the vaccine’s release. “I don’t need any side effects. I got enough going on with the body.”

Johnson lives in the 94605 ZIP code in Oakland — an area that has one of the lowest vaccination rates in the county with 62% fully inoculated compared with nearly 73% in all of Alameda County.

The 9-square-mile ZIP code is home to nearly 43,400 people. The neighborhoods are predominately Black and Latino. And about 14% of the population lives below the poverty line, according to the census reporter.

Oakland overall has fully vaccinated 70.3% of its more than 425,000 residents 12 and over, and administered at least one dose to 84.6%.

Recently, Alameda County partnered with community organizations to go door to door in neighborhoods to hand out masks, offer information on rental and food assistance programs, and urge people to get the vaccine, said Andrew Nelsen of the Alameda County Public Health Department’s health and equity planning unit.

“The way to reach people is to be the people you’re trying to reach,” Nelsen said. “Being talked at by an expert is very different than (talking) with a peer or a friend.”

Nelsen said there are a number of reasons people haven’t gotten vaccinated. Some don’t know where to go, some can’t go because they work long hours, and some people didn’t know it was free.

On a recent afternoon, Michele Custodio, 49, stopped outside a tent at Osita Health Clinic in East Oakland to schedule her second dose of the vaccine, something she has delayed.

Custodio said she’s read online that vaccines have microchips and can change DNA. These claims are false, but she and many other vaccine-hesitant people have found them compelling.

Also at Osita is 36-year-old Charlie Lloyd, who just received his first shot of Pfizer. Earlier in the day, he’d attended the funeral of a 40-year-old friend who’d died of COVID-19 a few weeks earlier. Lloyd said his friend’s death inspired him to get the shot.

“I couldn’t be happier right now,” Lloyd said after his shot. “I feel good about this.”

Outside an Antioch grocery store, cashier Cristina Diaz was waved down by county public health worker as soon as she stepped out the door, finally done with her shift on a Thursday in July.

“Have you been vaccinated?” the county staffer, Diana Aleman, said in Spanish.

Diaz, 30, nodded. But she immediately dialed her older sister and told her her to come to the store, Cielo Market on A Street — and try to persuade their reluctant father, too.

“They were just not doing it,” Diaz said.

This neighborhood of apartments and condos is tucked along Highway 4 in Antioch, a commuter city of about 110,000. Residents in this part of the city are young and impoverished: The median age is just over 26, and the per capita income is $16,000 — compared with $29,500 for all of Antioch and $48,000 for Contra Costa County.

They are also disproportionately unprotected by vaccines for COVID-19. About 18,000 people 12 and up are unvaccinated, representing about 33% of residents living in Antioch ZIP code 94509 — compared with nearly 24% of residents in all of Contra Costa County, according to state data. The data is more stark in the Sycamore neighborhood, where about 50% of those eligible for vaccines are at least partially vaccinated, compared with 69% of Antioch as a whole, the county said, and 76.4% for the county overall.

Generational mistrust of the government, misinformation and the crushing demands of work and poverty have conspired to leave these communities less protected by vaccinations, De La Torre said. Combating that, he realized, would take persistence and a light touch.

“Every person we get vaccinated is another person to bring that message back to their communities and share — ‘I got vaccinated, and I’m OK,’” he said.

After several hours at the market, the group piled into the van and drove less than a mile away to the QuikStop parking lot.

Nay Nay Daniels, 22, who was selling egg rolls and hibiscus drinks in the parking lot, pulled out her phone and showed a TikTok video purporting to depict first lady Jill Biden calling the vaccines an experiment. Daniels said she believed God would protect her and the government would not.

City Council Member Tamisha Torres-Walker joined the county volunteers to help provide a known and trusted voice to the mission in her district, a predominantly black and Latino area of Antioch. She acknowledged “it’s a big concern that not enough of our people are getting vaccinated.”

Torres-Walker, who is Black, said she understands vaccine hesitation given experiences of mistreatment and undertreatment of African Americans among some seeking care in medical settings. Torres-Walker, too, is hesitant to get vaccinated.

“Unfortunately it’s related to pre-existing historical trauma — people don’t trust the government,” Torres-Walker said.

De La Torre recalled a middle-aged man who drove past them several times before doubling back and calling out, “I’m scared.” They called back, saying he would be OK. He eventually agreed once he knew he could hold his dog on his lap while receiving a shot.

“We know we’re not going to change their mind right away,” De La Torre said. “If we maintain a presence, if we build trust, that could change.”

Julie Johnson, Nanette Asimov and Sarah Ravani are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: julie.johnson@sfchronicle.com, nasimov@sfchronicle.com, sravani@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @juliejohnson, @NanetteAsimov, @SarRavani

michaelrc

Dagobah Resident

If your sick, how will you fight back. . .

DR REINER FUELLMICH - THEY HAVE STOLEN YOUR PENSION FUNDS...

www.bitchute.com

www.bitchute.com

DR REINER FUELLMICH - THEY HAVE STOLEN YOUR PENSION FUNDS...

Dr Reiner Fuellmich - They Have STOLEN Your Pension Funds...

mirrored from 153Newsnet Mixed Pickles channel

SevenFeathers

Dagobah Resident

I know they say this is unique to "covid", but I don't think it is. About 10 years ago, I had a bad cold and I lost my sense of taste and smell for about a month. Not pleasant.Just a quick update on my covid situation - so the major update is I lost my taste / smell.

But anyway, all the best to you for a full recovery soon!

Hi_Henry

The Living Force

bjorb

The Living Force

In Australia, they now shoot rescued dogs to prevent shelter volunteers from leaving their homes to care for the dogs.

www.smh.com.au

www.smh.com.au

Rescue dogs shot dead by NSW council due to COVID-19 restrictions

Several impounded dogs have been shot by a rural council under its interpretation of COVID-19 restrictions.

bjorb

The Living Force

Dystopian: Manhunt for a 27-year-old Sydney man. Crime: tested positive. "The community is warned to avoid contact and not to approach him. Anyone with information about Mr Karam's whereabouts should call Crime Stoppers immediately."

Pushing back - funny how only official lies and duplicity are acceptable!

Meanwhile, a pastor at a California megachurch is offering religious exemptions for anyone morally conflicted over vaccines.

And Louisiana's attorney general has posted sample letters on his office's Facebook page for those seeking to get around the governor's mask rules.

Across the US, religious figures, public officials and other community leaders are helping circumvent COVID-19 precautions.

While proponents of these workarounds say they are looking out for children's health and parents' rights, others say such strategies are dishonest and could undermine efforts to defeat the highly contagious delta variant.

Mask and vaccine requirements vary from state to state, but often allow exemptions for certain medical conditions, or religious or philosophical objections.

In Oregon, Superintendent Marc Thielman of the rural Alsea School District told parents they can sidestep the governor's school mask requirement by applying for an accommodation for their children under federal disabilities law.

Thielman said he hit upon the idea after the governor's mandate generated 'huge, huge pushback' from parents.

'The majority of my parents are skeptical and are no longer believing what they're told' about COVID-19, said Thielman, whose district in the state´s coastal mountains begins classes Monday.

'I've got a majority of my parents saying, 'Are there any options?'

In a letter to educators this past week, Democratic Gov. Kate Brown said she was shocked that Thielman was undermining her policies by 'instructing students to lie' about having a disability.

Brown has mandated masks in schools and vaccinations for all school staff amid a surge in infections that is clobbering Oregon. The state has broken its record for COVID-19 hospitalizations day after day, and cases among children have increased dramatically. Thielman, who is planning to run for governor next year, when Brown can't seek reelection because of term limits, said he is not anti-mask but is sensitive to parents´ concerns that face coverings can cause anxiety and headaches in children.

In some cases, he said, he believes those problems justify an exemption under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 because they interfere with learning.

But Laurie VanderPloeg, an associate executive director at the Council for Exceptional Children, an advocacy group, cautioned that under the federal law, children would not be allowed to go maskless simply because they asked.

Under the law, she said, school districts would have to go through a formal process to establish whether a child does, in fact, have a particular mental or physical disability, such as a respiratory condition, that would warrant an exception to the mask rule.

In Kansas, the Spring Hill school board is allowing parents to claim a medical or mental health exemption from the county's requirement that elementary school students mask up. They do not need a medical provider to sign off.

Board member Ali Seeling said the idea is to give parents 'the freedom to make health decisions for their own children.'

Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, a Republican who regularly spars with Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards, posted sample letters that would allow parents to seek a philosophical or religious exemption from Edwards' mask rule at schools - or from a vaccine requirement, if one is enacted.

The letters have been shared by GOP lawmakers and thousands of others.

'Louisiana is not governed by a dictatorship. The question is: 'who gets to determine the healthcare choices for you and your child?' In a free society, the answer is the citizen - not the state,' Landry wrote on Facebook.

Edwards accused the attorney general of creating confusion and defended his policy on face coverings.

'By adopting these measures - and ignoring those that are unwilling to acknowledge the current crisis - we can keep our kids in school this year and keep them safe,' the governor said.

In California, the state medical board is investigating a doctor who critics say is handing out dozens of one-sentence mask exemptions for children in an attempt to evade the statewide school mask requirement.

Dr. Michael Huang, who has a practice in the Sacramento suburb of Roseville, declined to answer questions from The Associated Press but told other news outlets that he examines each child and issues exemptions appropriately. The California Medical Association issued a statement condemning 'rogue physicians' selling 'bogus' exemptions.

In a neighboring suburb, Pastor Greg Fairrington of Rocklin's Destiny Christian Church has issued at least 3,000 religious exemptions to people with objections to the vaccine, which is becoming mandatory in an increasing number of places in California.

He said in a statement that his church has received thousands of calls from doctors, nurses, teachers and first responders terrified of losing their jobs because they don´t want to get vaccinated. His office declined to share the exemption letter.

'We are not anti-vaccine,' he said. 'At the same time, we believe in the freedom of conscience and freedom of religion. The vaccine poses a morally compromising situation for many people of faith.'

Health experts such as Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, warned that such strategies will sow confusion about masks and vaccinations.

The virus is 'looking for fractures in the system,' he said, 'and we have plenty of fractures in the system.'

Oregon resident Jenny Jonak, who has an 11-year-old daughter with autism and health problems that make her more susceptible to COVID-19, said wearing masks is a 'very small inconvenience' to protect vulnerable students.

'If a child really has a genuine reason, if there´s some sort of breathing or respiratory problem, then that should be respected,' she said.

'But if not, then I don´t know what we're teaching our children if we're teaching them basically that something as simple as wearing a mask is something that they should bend the rules for.'

How does Jenny and all the narrative enforcing authorities not get that wearing masks creates a breathing/respiratory problem! There's nothing to be confused about other than their lies and obfuscation of the actual scientific facts! Why aren't these studies thrown into the enforcers' faces:

www.lifesitenews.com

www.lifesitenews.com

principia-scientific.com

principia-scientific.com

www.sott.net

www.sott.net

Oregon school official COACHES parents on how to get their children to escape mask mandate: Superintendent tells them to skirt rules by applying for exemption under federal disabilities law

An Oregon school superintendent is telling parents they can get their children out of wearing masks by citing a federal disability law.Meanwhile, a pastor at a California megachurch is offering religious exemptions for anyone morally conflicted over vaccines.

And Louisiana's attorney general has posted sample letters on his office's Facebook page for those seeking to get around the governor's mask rules.

Across the US, religious figures, public officials and other community leaders are helping circumvent COVID-19 precautions.

While proponents of these workarounds say they are looking out for children's health and parents' rights, others say such strategies are dishonest and could undermine efforts to defeat the highly contagious delta variant.

Mask and vaccine requirements vary from state to state, but often allow exemptions for certain medical conditions, or religious or philosophical objections.

In Oregon, Superintendent Marc Thielman of the rural Alsea School District told parents they can sidestep the governor's school mask requirement by applying for an accommodation for their children under federal disabilities law.

Thielman said he hit upon the idea after the governor's mandate generated 'huge, huge pushback' from parents.

'The majority of my parents are skeptical and are no longer believing what they're told' about COVID-19, said Thielman, whose district in the state´s coastal mountains begins classes Monday.

'I've got a majority of my parents saying, 'Are there any options?'

In a letter to educators this past week, Democratic Gov. Kate Brown said she was shocked that Thielman was undermining her policies by 'instructing students to lie' about having a disability.

Brown has mandated masks in schools and vaccinations for all school staff amid a surge in infections that is clobbering Oregon. The state has broken its record for COVID-19 hospitalizations day after day, and cases among children have increased dramatically. Thielman, who is planning to run for governor next year, when Brown can't seek reelection because of term limits, said he is not anti-mask but is sensitive to parents´ concerns that face coverings can cause anxiety and headaches in children.

In some cases, he said, he believes those problems justify an exemption under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 because they interfere with learning.

But Laurie VanderPloeg, an associate executive director at the Council for Exceptional Children, an advocacy group, cautioned that under the federal law, children would not be allowed to go maskless simply because they asked.

Under the law, she said, school districts would have to go through a formal process to establish whether a child does, in fact, have a particular mental or physical disability, such as a respiratory condition, that would warrant an exception to the mask rule.

In Kansas, the Spring Hill school board is allowing parents to claim a medical or mental health exemption from the county's requirement that elementary school students mask up. They do not need a medical provider to sign off.

Board member Ali Seeling said the idea is to give parents 'the freedom to make health decisions for their own children.'

Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, a Republican who regularly spars with Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards, posted sample letters that would allow parents to seek a philosophical or religious exemption from Edwards' mask rule at schools - or from a vaccine requirement, if one is enacted.

The letters have been shared by GOP lawmakers and thousands of others.

'Louisiana is not governed by a dictatorship. The question is: 'who gets to determine the healthcare choices for you and your child?' In a free society, the answer is the citizen - not the state,' Landry wrote on Facebook.

Edwards accused the attorney general of creating confusion and defended his policy on face coverings.

'By adopting these measures - and ignoring those that are unwilling to acknowledge the current crisis - we can keep our kids in school this year and keep them safe,' the governor said.

In California, the state medical board is investigating a doctor who critics say is handing out dozens of one-sentence mask exemptions for children in an attempt to evade the statewide school mask requirement.

Dr. Michael Huang, who has a practice in the Sacramento suburb of Roseville, declined to answer questions from The Associated Press but told other news outlets that he examines each child and issues exemptions appropriately. The California Medical Association issued a statement condemning 'rogue physicians' selling 'bogus' exemptions.

In a neighboring suburb, Pastor Greg Fairrington of Rocklin's Destiny Christian Church has issued at least 3,000 religious exemptions to people with objections to the vaccine, which is becoming mandatory in an increasing number of places in California.

He said in a statement that his church has received thousands of calls from doctors, nurses, teachers and first responders terrified of losing their jobs because they don´t want to get vaccinated. His office declined to share the exemption letter.

'We are not anti-vaccine,' he said. 'At the same time, we believe in the freedom of conscience and freedom of religion. The vaccine poses a morally compromising situation for many people of faith.'

Health experts such as Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, warned that such strategies will sow confusion about masks and vaccinations.

The virus is 'looking for fractures in the system,' he said, 'and we have plenty of fractures in the system.'

Oregon resident Jenny Jonak, who has an 11-year-old daughter with autism and health problems that make her more susceptible to COVID-19, said wearing masks is a 'very small inconvenience' to protect vulnerable students.

'If a child really has a genuine reason, if there´s some sort of breathing or respiratory problem, then that should be respected,' she said.

'But if not, then I don´t know what we're teaching our children if we're teaching them basically that something as simple as wearing a mask is something that they should bend the rules for.'

How does Jenny and all the narrative enforcing authorities not get that wearing masks creates a breathing/respiratory problem! There's nothing to be confused about other than their lies and obfuscation of the actual scientific facts! Why aren't these studies thrown into the enforcers' faces:

47 studies confirm ineffectiveness of masks for COVID and 32 more confirm their negative health effects - LifeSite

Young children being forced to wear masks is of particular concern.

65 Studies Reveals Face Masks DO Cause Physical Harm | Principia Scientific, Intl.

Image: DW Meta-Analysis of 65 Studies Reveals Face Masks Induce Mask-Induced Exhaustion Syndrome (MIES). A first-of-its-kind literature review on the adverse effects of face masks, titled "Is a Mask That Covers the Mouth and Nose Free from Undesirable Side Effects in Everyday Use and Free of...

German Neurologist Warns Against Wearing Facemasks: 'Oxygen Deprivation Causes Permanent Neurological Damage' -- Sott.net

This is one of the most important posts I have ever made, so please read it. I have written a transcript of some highlights from Dr. Margarite Griesz-Brisson's recent and extremely pressing video message, which was translated from German into...

Because it's a fact that masks are a psychological weapon to weaken, subjugate and control people, it's worthwhile to keep beating the drum of their ineffectiveness and actual harm:

Masks Are Neither Effective Nor Safe: A Summary Of The Science

Print this article and hand it to frightened mask wearers who have believed the alarmist media, politicians and Technocrats in white coats. Masks are proven ineffective against coronavirus and potentially harmful to healthy people and those with pre-existing conditions.

Are masks effective at preventing transmission of respiratory pathogens?

In this meta-analysis, face masks were found to have no detectable effect against transmission of viral infections. (1) It found: “Compared to no masks, there was no reduction of influenza-like illness cases or influenza for masks in the general population, nor in healthcare workers.”

This 2020 meta-analysis found that evidence from randomized controlled trials of face masks did not support a substantial effect on transmission of laboratory-confirmed influenza, either when worn by infected persons (source control) or by persons in the general community to reduce their susceptibility. (2)

Another recent review found that masks had no effect specifically against Covid-19, although facemask use seemed linked to, in 3 of 31 studies, “very slightly reduced” odds of developing influenza-like illness. (3)

This 2019 study of 2862 participants showed that both N95 respirators and surgical masks “resulted in no significant difference in the incidence of laboratory confirmed influenza.” (4)

This 2016 meta-analysis found that both randomized controlled trials and observational studies of N95 respirators and surgical masks used by healthcare workers did not show benefit against transmission of acute respiratory infections. It was also found that acute respiratory infection transmission “may have occurred via contamination of provided respiratory protective equipment during storage and reuse of masks and respirators throughout the workday.” (5)

A 2011 meta-analysis of 17 studies regarding masks and effect on transmission of influenza found that “none of the studies established a conclusive relationship between mask/respirator use and protection against influenza infection.” (6) However, authors speculated that effectiveness of masks may be linked to early, consistent and correct usage.

Face mask use was likewise found to be not protective against the common cold, compared to controls without face masks among healthcare workers. (7)

Airflow around masks

Masks have been assumed to be effective in obstructing forward travel of viral particles. Considering those positioned next to or behind a mask wearer, there have been farther transmission of virus-laden fluid particles from masked individuals than from unmasked individuals, by means of “several leakage jets, including intense backward and downwards jets that may present major hazards,” and a “potentially dangerous leakage jet of up to several meters.” (8) All masks were thought to reduce forward airflow by 90% or more over wearing no mask. However, Schlieren imaging showed that both surgical masks and cloth masks had farther brow jets (unfiltered upward airflow past eyebrows) than not wearing any mask at all, 182 mm and 203 mm respectively, vs none discernible with no mask. Backward unfiltered airflow was found to be strong with all masks compared to not masking.

For both N95 and surgical masks, it was found that expelled particles from 0.03 to 1 micron were deflected around the edges of each mask, and that there was measurable penetration of particles through the filter of each mask. (9)

Penetration through masks

A study of 44 mask brands found mean 35.6% penetration (+ 34.7%). Most medical masks had over 20% penetration, while “general masks and handkerchiefs had no protective function in terms of the aerosol filtration efficiency.” The study found that “Medical masks, general masks, and handkerchiefs were found to provide little protection against respiratory aerosols.” (10)

It may be helpful to remember that an aerosol is a colloidal suspension of liquid or solid particles in a gas. In respiration, the relevant aerosol is the suspension of bacterial or viral particles in inhaled or exhaled breath.

In another study, penetration of cloth masks by particles was almost 97% and medical masks 44%. (11)

N95 respirators

Honeywell is a manufacturer of N95 respirators. These are made with a 0.3 micron filter. (12) N95 respirators are so named, because 95% of particles having a diameter of 0.3 microns are filtered by the mask forward of the wearer, by use of an electrostatic mechanism. Coronaviruses are approximately 0.125 microns in diameter.

This meta-analysis found that N95 respirators did not provide superior protection to facemasks against viral infections or influenza-like infections. (13) This study did find superior protection by N95 respirators when they were fit-tested compared to surgical masks. (14)

This study found that 624 out of 714 people wearing N95 masks left visible gaps when putting on their own masks. (15)

Surgical masks

This study found that surgical masks offered no protection at all against influenza. (16) Another study found that surgical masks had about 85% penetration ratio of aerosolized inactivated influenza particles and about 90% of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, although S aureus particles were about 6x the diameter of influenza particles. (17)

Use of masks in surgery were found to slightly increase incidence of infection over not masking in a study of 3,088 surgeries. (18) The surgeons’ masks were found to give no protective effect to the patients.

Other studies found no difference in wound infection rates with and without surgical masks. (19) (20)

This study found that “there is a lack of substantial evidence to support claims that facemasks protect either patient or surgeon from infectious contamination.” (21)

This study found that medical masks have a wide range of filtration efficiency, with most showing a 30% to 50% efficiency. (22)

Specifically, are surgical masks effective in stopping human transmission of coronaviruses? Both experimental and control groups, masked and unmasked respectively, were found to “not shed detectable virus in respiratory droplets or aerosols.” (23) In that study, they “did not confirm the infectivity of coronavirus” as found in exhaled breath.

A study of aerosol penetration showed that two of the five surgical masks studied had 51% to 89% penetration of polydisperse aerosols. (24)

In another study, that observed subjects while coughing, “neither surgical nor cotton masks effectively filtered SARS-CoV-2 during coughs by infected patients.” And more viral particles were found on the outside than on the inside of masks tested. (25)

Cloth masks

Cloth masks were found to have low efficiency for blocking particles of 0.3 microns and smaller. Aerosol penetration through the various cloth masks examined in this study were between 74 and 90%. Likewise, the filtration efficiency of fabric materials was 3% to 33% (26)

Healthcare workers wearing cloth masks were found to have 13 times the risk of influenza-like illness than those wearing medical masks. (27)

This 1920 analysis of cloth mask use during the 1918 pandemic examines the failure of masks to impede or stop flu transmission at that time, and concluded that the number of layers of fabric required to prevent pathogen penetration would have required a suffocating number of layers, and could not be used for that reason, as well as the problem of leakage vents around the edges of cloth masks. (28)

Masks against Covid-19

The New England Journal of Medicine editorial on the topic of mask use versus Covid-19 assesses the matter as follows:

“We know that wearing a mask outside health care facilities offers little, if any, protection from infection. Public health authorities define a significant exposure to Covid-19 as face-to-face contact within 6 feet with a patient with symptomatic Covid-19 that is sustained for at least a few minutes (and some say more than 10 minutes or even 20 minutes). The chance of catching Covid-19 from a passing interaction in a public space is therefore minimal. In many cases, the desire for widespread masking is a reflexive reaction to anxiety over the pandemic.” (29)

Are masks safe?

During walking or other exercise

Surgical mask wearers had significantly increased dyspnea after a 6-minute walk than non-mask wearers. (30)

Researchers are concerned about possible burden of facemasks during physical activity on pulmonary, circulatory and immune systems, due to oxygen reduction and air trapping reducing substantial carbon dioxide exchange. As a result of hypercapnia, there may be cardiac overload, renal overload, and a shift to metabolic acidosis. (31)

Risks of N95 respirators

Pregnant healthcare workers were found to have a loss in volume of oxygen consumption by 13.8% compared to controls when wearing N95 respirators. 17.7% less carbon dioxide was exhaled. (32) Patients with end-stage renal disease were studied during use of N95 respirators. Their partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) decreased significantly compared to controls and increased respiratory adverse effects. (33) 19% of the patients developed various degrees of hypoxemia while wearing the masks.

Healthcare workers’ N95 respirators were measured by personal bioaerosol samplers to harbor influenza virus. (34) And 25% of healthcare workers’ facepiece respirators were found to contain influenza in an emergency department during the 2015 flu season. (35)

Risks of surgical masks

Healthcare workers’ surgical masks also were measured by personal bioaerosol samplers to harbor for influenza virus. (36)

Various respiratory pathogens were found on the outer surface of used medical masks, which could result in self-contamination. The risk was found to be higher with longer duration of mask use. (37)

Surgical masks were also found to be a repository of bacterial contamination. The source of the bacteria was determined to be the body surface of the surgeons, rather than the operating room environment. (38) Given that surgeons are gowned from head to foot for surgery, this finding should be especially concerning for laypeople who wear masks. Without the protective garb of surgeons, laypeople generally have even more exposed body surface to serve as a source for bacteria to collect on their masks.

Risks of cloth masks

Healthcare workers wearing cloth masks had significantly higher rates of influenza-like illness after four weeks of continuous on-the-job use, when compared to controls. (39)

The increased rate of infection in mask-wearers may be due to a weakening of immune function during mask use. Surgeons have been found to have lower oxygen saturation after surgeries even as short as 30 minutes. (40) Low oxygen induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1). (41) This in turn down-regulates CD4+ T-cells. CD4+ T-cells, in turn, are necessary for viral immunity. (42)

Weighing risks versus benefits of mask use

In the summer of 2020 the United States is experiencing a surge of popular mask use, which is frequently promoted by the media, political leaders and celebrities. Homemade and store-bought cloth masks and surgical masks or N95 masks are being used by the public especially when entering stores and other publicly accessible buildings. Sometimes bandanas or scarves are used. The use of face masks, whether cloth, surgical or N95, creates a poor obstacle to aerosolized pathogens as we can see from the meta-analyses and other studies in this paper, allowing both transmission of aerosolized pathogens to others in various directions, as well as self-contamination.

It must also be considered that masks impede the necessary volume of air intake required for adequate oxygen exchange, which results in observed physiological effects that may be undesirable. Even 6- minute walks, let alone more strenuous activity, resulted in dyspnea. The volume of unobstructed oxygen in a typical breath is about 100 ml, used for normal physiological processes. 100 ml O2 greatly exceeds the volume of a pathogen required for transmission.

The foregoing data show that masks serve more as instruments of obstruction of normal breathing, rather than as effective barriers to pathogens. Therefore, masks should not be used by the general public, either by adults or children, and their limitations as prophylaxis against pathogens should also be considered in medical settings.

Endnotes

Trending content

-

Thread 'Coronavirus Pandemic: Apocalypse Now! Or exaggerated scare story?'

- wanderingthomas

Replies: 30K -

-

-