I thought I'd start a thread on this book, as recommended by Laura here.

Looks to be a very interesting read, and while I was looking to order it on the net, I came across an article excerpted from the book, which I will post here (link to the article is below):

[quote author= Heller & LaPierre]

The spontaneous movement in all of us is toward connection, health, and aliveness. No matter how withdrawn and isolated we have become, or how serious the trauma we have experienced, on the deepest level, just as a plant spontaneously moves toward sunlight, there is in each of us an impulse moving toward connection and healing.

It is the experience of being in connection that fulfills the longing we have to feel fully alive. An impaired capacity for connection to self and others and the ensuing diminished aliveness are the hidden dimensions that underlie most psychological and many physiological problems. Unfortunately, we are often unaware of the internal roadblocks that keep us from the experience of the connection and aliveness we yearn for. When individuals have had to cope with early threat and the resulting high arousal of unresolved anger and incompleted fight-flight responses, adaptive survival mechanisms develop that reflect the dysregulation of the nervous system and of all the systems of the body. These adaptive survival mechanisms disrupt the capacity for connection and social engagement and are the threads that link the many physical, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms that are the markers of developmental posttraumatic stress.

A Brief Historical Context

A cornerstone of somatic psychotherapy has been that our aliveness, vitality, and authenticity are accessed through connection to the body. As we know, Western somatic psychotherapy began with Wilhelm Reich who was the first to understand that our biologically based emotions are inextricably linked to our psychological processes. Reich, whose roots were in psychoanalysis, is best known for his insights on what he called character structures, which he believed were kept in place by defensive armoring. For Reich, the term armoring refers to the muscular rigidity that is the protective response to living in environments that are emotionally repressive and hostile to aliveness. Building on Reich’s understanding of the functional unity of body and mind, Alexander Lowen developed Bioenergetics, a somatic approach that identified five basic developmental character structures: schizoid, oral, psychopathic, masochistic, and rigid. Lowen’s five character structures clearly tapped into a fundamental understanding of human nature and have influenced many subsequent body-based psychotherapies. Reich and Lowen’s character structures were based on the medical model of disease and therefore focused on the pathology of each developmental stage. Consistent with the thinking of their time, they emphasized the importance of working with defenses, repression, and resistance and encouraged regression, abreaction, and catharsis. Reich and Lowen both believed that the therapist’s job was to break through a patient’s character armor—their psychological and somatic defenses—in order to release the painful emotions stored or locked in the body.

As new information has emerged on how the brain and nervous system function, the need to update the focus on pathology in both psychodynamic and somatic approaches is becoming increasingly clear. Looking through the lens of what we currently know about trauma and its impact on the nervous system, cathartic interventions can have the unintended effect of causing increased fragmentation and retraumatization. For example, we now know that when we focus on dysfunction, we risk reinforcing that dysfunction: if we focus on deficiency and pain, we are likely to get better at feeling deficiency and pain. Similarly, when we concentrate primarily on an individual’s past, we build skills at reflecting on the past, sometimes making personal history seem more important than present experience.

Five Biologically Based Core Needs and Associated Capacities

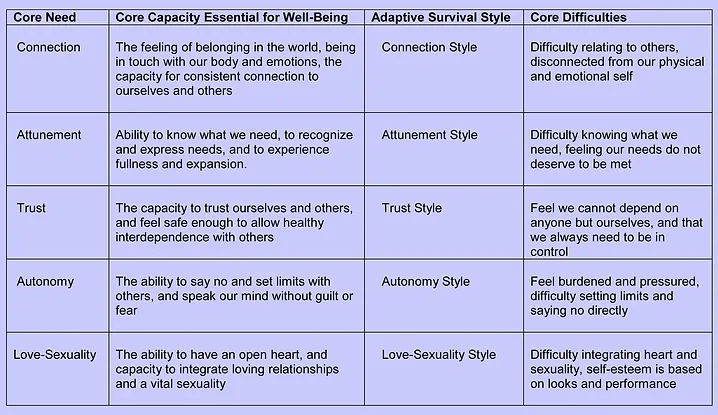

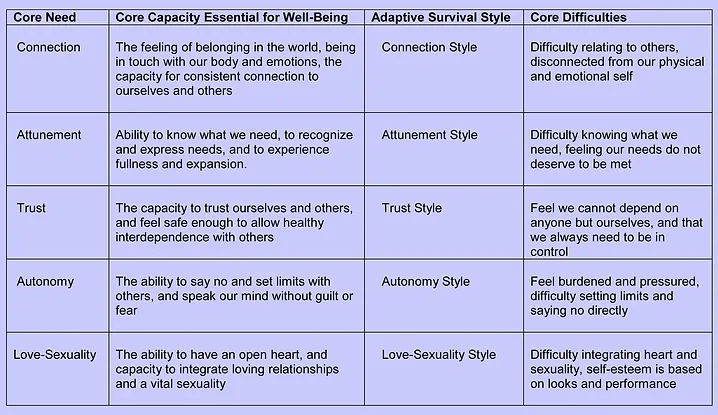

Reconceptualizing the character structure model to take current knowledge into account, the NeuroAffective Relational Model™(NARM) recognizes five biologically based core needs that are essential to our physical and emotional well-being: the need for connection, attunement, trust, autonomy, and love-sexuality (Table 2). When our biologically based core needs are met early in life, we develop core capacities that allow us to recognize and meet these core needs as adults. Being attuned to these five basic needs and capacities means that we are connected to our deepest resources and vitality.

Although it may seem that humans suffer from an endless number of emotional problems and challenges, most of these can be traced to early developmental traumas that compromise the development of one or more of the five core capacities. Using the first two core needs as examples, when children do not get the connection they need, they grow up both seeking and fearing connection. When children do not get the necessary early attunement to their needs, they do not learn to recognize what they need, are unable to express their needs, and often feel undeserving of having their needs met. When a biologically based core need is not met, predictable psychological and physiological symptoms result: self-regulation, identity, and self-esteem become compromised. To the degree that the five biologically based core needs are not met in early life, five corresponding adaptive survival styles are set in motion. These survival styles are the adaptive strategies children develop to cope with the disconnection, dysregulation, disorganization, and isolation they experience when core needs are not met. Each adaptive survival styles is named for its core need and missing or compromised core capacity: the Connection Survival Style, the Attunement Survival Style, the Trust Survival Style, the Autonomy Survival Style, and the LoveSexuality Survival Style

As adults, the more the five adaptive survival styles dominate our lives, the more disconnected we are from our bodies, the more distorted our sense of identity becomes, and the less we are able to regulate ourselves. When, because of developmental trauma, we are identified with a survival style, we stay within the confines of learned and subsequently self-imposed limitations, foreclosing our capacity for connection and aliveness. To illustrate how in NARM we support the development of missing core capacities and help clients disidentify from the resulting adaptive survival styles, we will now focus on the treatment of adults who struggle with the Connection Survival Style. The theme of broken connection runs through all five survival styles, but it is particularly central to the Connection Survival Style.

CONNECTION

Our First Core Need

In NARM, Connection is the name given to the first stage of human development and the first core need or organizing life principle. When our capacity for connection is in place, we experience a right to be that

becomes the foundation upon which our healthy self and our vital relationship to life is built. The degree to which we feel received, loved, and welcomed into the world makes up the cornerstone of our identity. The Connection Survival Style, what Lowen called the schizoid, develops as a way of coping with the systemic high-arousal states that result from the ongoing attachment distress of feeling unloved, unprotected, unsupported, and even hated.

The Interplay Between Shock and Developmental Trauma

Shock trauma—the impact of an acute, devastating incident that leaves an individual frozen in fear and frozen in time—is clinically recognized and treated under the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder

(PTSD). In single-event shock trauma, the completion of the fight–flight response is not possible. When working with individuals who have experienced shock trauma, the goal of therapy is to help them complete the fight–flight response. In cases of developmental trauma—which includes profound caregiver misattunement as well as ongoing abuse and neglect of varying degrees—there is no single traumatizing event. Although the physiological response may be similar to that of shock trauma, there are ongoing distressing relational dynamics to take into consideration. Throughout the stages of a child’s development, there is an interplay between shock and developmental trauma. In early development, shock traumas—for example early surgery, an infant’s or mother’s illness, death in the family, or global events such as being born into wartime—have a disruptive effect on the attachment process. In these situations, infants are affected not only by the shock itself, but also by how the shock negatively impacts the attachment process. An example of the interplay between shock and developmental trauma can be seen in infants who have experienced prenatal trauma. At birth, the already traumatized infant is in a disorganized and dysregulated state. Studies show that it is more difficult for a mother to bond with a distressed baby. Traumatized infants present their mothers with significant regulation and attachment challenges that do not exist in non-traumatized newborns.

The Impact of Trauma on Early Development

During the first stage of life, the fetus and the infant are in every way dependent on their caregivers and on their environment. As a result of this complete vulnerability, an infant’s reaction to early developmental or shock trauma is one of overwhelmingly high arousal and terror. The vulnerable infant, who can neither fight nor flee, cannot discharge the high arousal caused by the uncontrollable threat and responds with physiological constriction, contraction, core withdrawal, and immobility/freeze. One of the strategies used by animals in response to threat is to run for safety. Animals run to their burrows, flee to their caves or to any other safe place. When infants or small children experience early shock or attachment trauma, the threat is inescapable. They cannot run and they cannot fight. Whether the threat is intrauterine or takes place at birth or later in life, there is no possible safety other than that provided by the caregivers. When their caregivers, for whatever reason, are unable to provide safety or are themselves a source of threat, infants experience the only home they have as unsafe; this sets up a pattern for a lifelong sense that the world is unsafe. The earlier the trauma, the more global its impact on the physiology and psychology, on the sense of identity and world view.

Current studies in developmental traumatology show that the cumulative effects of chronic early neglect and abuse adversely influence brain development and negatively impact the nervous system, endocrine system, and memory. The pain of early trauma is overwhelming and disorganizing; it creates high levels of systemic arousal and stress which, when ongoing and undischarged, are managed in the body through visceral dysregulation, muscular contraction, and the dissociative processes of numbing, splitting, and fragmentation. Anyone who has pricked an amoeba and seen it contract and close in on itself has witnessed this process of contraction and withdrawal. This combination of high arousal, contraction, and withdrawal/freeze creates systemic dysregulation that affects all of the body’s biological systems leaving the child and later the adult with a narrowed range of resiliency and an increased vulnerability to later traumas. The underlying biological dysregulation of early trauma is the shaky foundation upon which the psychological self is built.

When infants experience their environment as threatening and dangerous, their reaction is either to cling to others or to withdraw into themselves. As with all living organisms, constriction, contraction, withdrawal, and freeze are the primitive defenses infants utilize to manage the high arousal of terrifying early trauma. When threat is chronic, when danger never goes away and there is no possible resolution as is the case in abusive families, the entire organism remains in ongoing anxious and defensive responses and the nervous system becomes locked in a state of high sympathetic arousal and hypervigilance. In cases of early or severe trauma, when infants cannot run from threat or fight back, arousal levels can be so dangerously high that they threaten to overload the nervous system, and often do so. Locked in perpetual, painful high arousal, the only alternative, the fallback position, is to go into a freeze state which infants and small children accomplish by numbing themselves. Until the trauma response is completed and the high levels of arousal are discharged from the nervous system, the environment continues to feel unsafe even when the actual threat is gone. Being locked in unresolved trauma responses can become a lifelong state, as we see in individuals with the Connection Survival Style.

Early Trauma Is Held in Implicit Memory

Since the hippocampus is responsible for discrete memory, when trauma occurs early in the development of the neocortex and before the hippocampus comes online, many individuals show symptoms of

developmental posttraumatic stress yet have no conscious memories of traumatic events. Early trauma is held implicitly in the body and brain resulting in a systemic dysregulation that is confusing for individuals who often exhibit symptoms of traumas they cannot remember. This is also confusing for the clinicians who want to help them. Neuroscience confirms that early trauma is particularly damaging. Not only does it impact the body, nervous system, and developing psyche, but its effects are cumulative; trauma experienced in an early phase of development makes a child more vulnerable to trauma in later phases of development. For example, prenatal trauma can make birth more difficult, and a traumatic birth can affect the subsequent process of attachment. The tragedy of early trauma is that when babies resort to freeze and dissociation before the brain and nervous system have fully developed, their range of resiliency drastically narrows. In addition to the normal challenges of childhood, meeting later developmental tasks becomes that much more difficult. Being stuck in freeze-dissociation, these individuals have less access to healthy aggression, including the fight–flight response, and their capacity for social engagement is strongly impaired, leaving them much more vulnerable and less able to cope with later trauma and the challenges of life.

The Adult Experience

Adults who have experienced early trauma are engaged in a lifelong struggle to manage their high levels of arousal. They struggle with dissociative responses that disconnect them from their body, with the

vulnerability of ruptured boundaries, and with the dysregulation that accompanies such struggles. Individuals with less obvious symptoms may not consciously realize that they experience a diminished

capacity for joy, expansion, and intimate relationship; if they are aware of their difficulties, they usually do not understand their source. Individuals with the Connection Survival Style are often relieved to learn that their difficult symptoms have a common thread, what we call an organizing principle. Their struggle with high levels of anxiety, psychological and physiological problems, chronic low self-esteem, shame, and dissociation all constellate around the organizing principle of connection—both the desire for connection and the fear of connection.

When there is early trauma, varying degrees of predictable symptoms are commonly present. It is important to keep in mind that these symptoms usually occur simultaneously, loop back on each other, and continuously reinforce one another.

• Self-Image and Self-Esteem. Individuals traumatized in the Connection stage experience themselves as outsiders, disconnected from themselves and other human beings. Not able to see that the traumatic experiences that shaped their identity are due to environmental failures that were beyond their control, individuals with the Connection Survival style view themselves as the source of the pain they feel.

• The Need to Isolate. Because of the breach in their energetic boundaries, individuals with the Connection Survival Style use interpersonal distance to feel safe. They develop life strategies to minimize contact with other human beings.

• Nameless Dread. The internal experience of adults traumatized in the Connection stage is one of constant underlying dread and terror characterized in NARM as nameless dread. Their nervous system has remained in a continual sympathetically dominant global high arousal and it is this arousal that drives and reinforces their profound and persistent feeling of threat.

• A Designated Issue. A named and identified threat is better than nameless dread. Not realizing that the danger that they once experienced in their environment is now being carried forward as high arousal in their nervous system, the tendency is to project onto the current environment what has become an ongoing internal state. Once the dread has been named, it becomes what we call the designated issue. The designated issue can be fear of death, a phobia, real or perceived physical deficiencies such as overweight or other perceived “defects”, as well as real or perceived psychological or cognitive deficiencies such as dyslexia or not feeling smart enough. Designated issues, whether or not they have a basis in physical reality, come to dominate a person’s life, covering the deeper distress and masking the underlying core disconnection.

• Shame and Self-Hatred. Infants who experience early trauma of any kind experience the early environmental failure as if there were something wrong with them. Later cognitions such as “There is something basically wrong with me” or “I am bad” are built upon the early somatic sensation: “I feel bad.”

• Overwhelm. People with significantly compromised energetic boundaries describe themselves as feeling raw, sometimes without a skin. Compromised energetic boundaries lead to the feeling of

being flooded by environmental stimuli and particularly by human contact.

• Environmental Sensitivities. Intact energetic boundaries function to filter environmental stimuli. Inadequate or compromised boundaries, on the other hand, allow for an extreme sensitivity to external stimuli: human contact, sounds, light, touch, toxins, allergens, smells, and even electromagnetic activity.

• A Sense of Meaninglessness. A common refrain from individuals with the Connection Survival Style is “Life has no meaning” or “What’s the point?” Searching for meaning, for the why of existence, is one of the primary coping mechanisms used for managing their sense of disconnection and despair.

Dissociation: Bearing the Unbearable

When trauma is early or severe, some individuals completely disconnect by numbing all sensation and emotion. Disconnection from the bodily self, emotions, and other people is traditionally called dissociation. By dissociating, that is, by keeping threat from overwhelming consciousness, a traumatized individual can continue to function. When individuals are dissociated, they have little or no awareness that they are dissociated: they only become aware of their dissociation as they come out of it. Compassionate understanding for the pain and fear that drives the dissociative process is critical to healing the Connection dynamic. Just as a coyote with its leg caught in a trap chews it off in order to escape, in attempting to manage early trauma, the organism fragments, sacrificing unity in order to save itself. Disconnection sets up a pernicious cycle: To manage early trauma, children disconnect from their bodies, emotions, and aggression, foreclosing their vitality and aliveness. In addition, they also disconnect from other people. This disconnection, though life saving, produces more distress because they feel exiled from self and others. Seeing other people live in what one client called “the circle of love” and the distress of feeling “on the outside looking in” heighten both shame and alienation. [/quote]

The rest of the article can be read here _http://cellularbalance.com/Articles/Working_with_Developmental_Trauma.pdf

I can relate to much of what is written above- when I was reading it I felt like a light bulb just went on. Can't wait to read the book in full.

Laura said:In respect of Neurofeedback training, I think that peeps should get and read "Healing Developmental Trauma" by Heller and Lapierre. I have just about finished it and WHAT a REVELATION. I posted about it in two other threads where it was mentioned:

https://cassiopaea.org/forum/index.php/topic,45226.msg747485.html#msg747485

https://cassiopaea.org/forum/index.php/topic,44868.msg747484.html#msg747484

... in hopes that more forum peeps will get and read this one!!!

I think that the information in this book (which combines a lot of things we already know and discuss, including Porges' "Polyvagal Theory") combined with The Work, AND Neurofeedback training, can be great assets to our toolkit for working on ourselves to become fully functional human beings with the potential to go beyond. It really can become a "Fourth Way" in every sense of the term. (And, of course, tending to the body via diet is also important, as we have found.)

So, peeps, get and read this book. It describes five types of survival strategies, i.e. false personalities, and maybe you can recognize yourself and better understand how to go forward, how to change the future by healing the past which can only be done IN the NOW.

Looks to be a very interesting read, and while I was looking to order it on the net, I came across an article excerpted from the book, which I will post here (link to the article is below):

[quote author= Heller & LaPierre]

The spontaneous movement in all of us is toward connection, health, and aliveness. No matter how withdrawn and isolated we have become, or how serious the trauma we have experienced, on the deepest level, just as a plant spontaneously moves toward sunlight, there is in each of us an impulse moving toward connection and healing.

It is the experience of being in connection that fulfills the longing we have to feel fully alive. An impaired capacity for connection to self and others and the ensuing diminished aliveness are the hidden dimensions that underlie most psychological and many physiological problems. Unfortunately, we are often unaware of the internal roadblocks that keep us from the experience of the connection and aliveness we yearn for. When individuals have had to cope with early threat and the resulting high arousal of unresolved anger and incompleted fight-flight responses, adaptive survival mechanisms develop that reflect the dysregulation of the nervous system and of all the systems of the body. These adaptive survival mechanisms disrupt the capacity for connection and social engagement and are the threads that link the many physical, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms that are the markers of developmental posttraumatic stress.

A Brief Historical Context

A cornerstone of somatic psychotherapy has been that our aliveness, vitality, and authenticity are accessed through connection to the body. As we know, Western somatic psychotherapy began with Wilhelm Reich who was the first to understand that our biologically based emotions are inextricably linked to our psychological processes. Reich, whose roots were in psychoanalysis, is best known for his insights on what he called character structures, which he believed were kept in place by defensive armoring. For Reich, the term armoring refers to the muscular rigidity that is the protective response to living in environments that are emotionally repressive and hostile to aliveness. Building on Reich’s understanding of the functional unity of body and mind, Alexander Lowen developed Bioenergetics, a somatic approach that identified five basic developmental character structures: schizoid, oral, psychopathic, masochistic, and rigid. Lowen’s five character structures clearly tapped into a fundamental understanding of human nature and have influenced many subsequent body-based psychotherapies. Reich and Lowen’s character structures were based on the medical model of disease and therefore focused on the pathology of each developmental stage. Consistent with the thinking of their time, they emphasized the importance of working with defenses, repression, and resistance and encouraged regression, abreaction, and catharsis. Reich and Lowen both believed that the therapist’s job was to break through a patient’s character armor—their psychological and somatic defenses—in order to release the painful emotions stored or locked in the body.

As new information has emerged on how the brain and nervous system function, the need to update the focus on pathology in both psychodynamic and somatic approaches is becoming increasingly clear. Looking through the lens of what we currently know about trauma and its impact on the nervous system, cathartic interventions can have the unintended effect of causing increased fragmentation and retraumatization. For example, we now know that when we focus on dysfunction, we risk reinforcing that dysfunction: if we focus on deficiency and pain, we are likely to get better at feeling deficiency and pain. Similarly, when we concentrate primarily on an individual’s past, we build skills at reflecting on the past, sometimes making personal history seem more important than present experience.

Five Biologically Based Core Needs and Associated Capacities

Reconceptualizing the character structure model to take current knowledge into account, the NeuroAffective Relational Model™(NARM) recognizes five biologically based core needs that are essential to our physical and emotional well-being: the need for connection, attunement, trust, autonomy, and love-sexuality (Table 2). When our biologically based core needs are met early in life, we develop core capacities that allow us to recognize and meet these core needs as adults. Being attuned to these five basic needs and capacities means that we are connected to our deepest resources and vitality.

{I could not paste the Table from the article, this is one from the internet}

Five Adaptive Survival StylesAlthough it may seem that humans suffer from an endless number of emotional problems and challenges, most of these can be traced to early developmental traumas that compromise the development of one or more of the five core capacities. Using the first two core needs as examples, when children do not get the connection they need, they grow up both seeking and fearing connection. When children do not get the necessary early attunement to their needs, they do not learn to recognize what they need, are unable to express their needs, and often feel undeserving of having their needs met. When a biologically based core need is not met, predictable psychological and physiological symptoms result: self-regulation, identity, and self-esteem become compromised. To the degree that the five biologically based core needs are not met in early life, five corresponding adaptive survival styles are set in motion. These survival styles are the adaptive strategies children develop to cope with the disconnection, dysregulation, disorganization, and isolation they experience when core needs are not met. Each adaptive survival styles is named for its core need and missing or compromised core capacity: the Connection Survival Style, the Attunement Survival Style, the Trust Survival Style, the Autonomy Survival Style, and the LoveSexuality Survival Style

As adults, the more the five adaptive survival styles dominate our lives, the more disconnected we are from our bodies, the more distorted our sense of identity becomes, and the less we are able to regulate ourselves. When, because of developmental trauma, we are identified with a survival style, we stay within the confines of learned and subsequently self-imposed limitations, foreclosing our capacity for connection and aliveness. To illustrate how in NARM we support the development of missing core capacities and help clients disidentify from the resulting adaptive survival styles, we will now focus on the treatment of adults who struggle with the Connection Survival Style. The theme of broken connection runs through all five survival styles, but it is particularly central to the Connection Survival Style.

CONNECTION

Our First Core Need

In NARM, Connection is the name given to the first stage of human development and the first core need or organizing life principle. When our capacity for connection is in place, we experience a right to be that

becomes the foundation upon which our healthy self and our vital relationship to life is built. The degree to which we feel received, loved, and welcomed into the world makes up the cornerstone of our identity. The Connection Survival Style, what Lowen called the schizoid, develops as a way of coping with the systemic high-arousal states that result from the ongoing attachment distress of feeling unloved, unprotected, unsupported, and even hated.

The Interplay Between Shock and Developmental Trauma

Shock trauma—the impact of an acute, devastating incident that leaves an individual frozen in fear and frozen in time—is clinically recognized and treated under the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder

(PTSD). In single-event shock trauma, the completion of the fight–flight response is not possible. When working with individuals who have experienced shock trauma, the goal of therapy is to help them complete the fight–flight response. In cases of developmental trauma—which includes profound caregiver misattunement as well as ongoing abuse and neglect of varying degrees—there is no single traumatizing event. Although the physiological response may be similar to that of shock trauma, there are ongoing distressing relational dynamics to take into consideration. Throughout the stages of a child’s development, there is an interplay between shock and developmental trauma. In early development, shock traumas—for example early surgery, an infant’s or mother’s illness, death in the family, or global events such as being born into wartime—have a disruptive effect on the attachment process. In these situations, infants are affected not only by the shock itself, but also by how the shock negatively impacts the attachment process. An example of the interplay between shock and developmental trauma can be seen in infants who have experienced prenatal trauma. At birth, the already traumatized infant is in a disorganized and dysregulated state. Studies show that it is more difficult for a mother to bond with a distressed baby. Traumatized infants present their mothers with significant regulation and attachment challenges that do not exist in non-traumatized newborns.

The Impact of Trauma on Early Development

During the first stage of life, the fetus and the infant are in every way dependent on their caregivers and on their environment. As a result of this complete vulnerability, an infant’s reaction to early developmental or shock trauma is one of overwhelmingly high arousal and terror. The vulnerable infant, who can neither fight nor flee, cannot discharge the high arousal caused by the uncontrollable threat and responds with physiological constriction, contraction, core withdrawal, and immobility/freeze. One of the strategies used by animals in response to threat is to run for safety. Animals run to their burrows, flee to their caves or to any other safe place. When infants or small children experience early shock or attachment trauma, the threat is inescapable. They cannot run and they cannot fight. Whether the threat is intrauterine or takes place at birth or later in life, there is no possible safety other than that provided by the caregivers. When their caregivers, for whatever reason, are unable to provide safety or are themselves a source of threat, infants experience the only home they have as unsafe; this sets up a pattern for a lifelong sense that the world is unsafe. The earlier the trauma, the more global its impact on the physiology and psychology, on the sense of identity and world view.

Current studies in developmental traumatology show that the cumulative effects of chronic early neglect and abuse adversely influence brain development and negatively impact the nervous system, endocrine system, and memory. The pain of early trauma is overwhelming and disorganizing; it creates high levels of systemic arousal and stress which, when ongoing and undischarged, are managed in the body through visceral dysregulation, muscular contraction, and the dissociative processes of numbing, splitting, and fragmentation. Anyone who has pricked an amoeba and seen it contract and close in on itself has witnessed this process of contraction and withdrawal. This combination of high arousal, contraction, and withdrawal/freeze creates systemic dysregulation that affects all of the body’s biological systems leaving the child and later the adult with a narrowed range of resiliency and an increased vulnerability to later traumas. The underlying biological dysregulation of early trauma is the shaky foundation upon which the psychological self is built.

When infants experience their environment as threatening and dangerous, their reaction is either to cling to others or to withdraw into themselves. As with all living organisms, constriction, contraction, withdrawal, and freeze are the primitive defenses infants utilize to manage the high arousal of terrifying early trauma. When threat is chronic, when danger never goes away and there is no possible resolution as is the case in abusive families, the entire organism remains in ongoing anxious and defensive responses and the nervous system becomes locked in a state of high sympathetic arousal and hypervigilance. In cases of early or severe trauma, when infants cannot run from threat or fight back, arousal levels can be so dangerously high that they threaten to overload the nervous system, and often do so. Locked in perpetual, painful high arousal, the only alternative, the fallback position, is to go into a freeze state which infants and small children accomplish by numbing themselves. Until the trauma response is completed and the high levels of arousal are discharged from the nervous system, the environment continues to feel unsafe even when the actual threat is gone. Being locked in unresolved trauma responses can become a lifelong state, as we see in individuals with the Connection Survival Style.

Early Trauma Is Held in Implicit Memory

Since the hippocampus is responsible for discrete memory, when trauma occurs early in the development of the neocortex and before the hippocampus comes online, many individuals show symptoms of

developmental posttraumatic stress yet have no conscious memories of traumatic events. Early trauma is held implicitly in the body and brain resulting in a systemic dysregulation that is confusing for individuals who often exhibit symptoms of traumas they cannot remember. This is also confusing for the clinicians who want to help them. Neuroscience confirms that early trauma is particularly damaging. Not only does it impact the body, nervous system, and developing psyche, but its effects are cumulative; trauma experienced in an early phase of development makes a child more vulnerable to trauma in later phases of development. For example, prenatal trauma can make birth more difficult, and a traumatic birth can affect the subsequent process of attachment. The tragedy of early trauma is that when babies resort to freeze and dissociation before the brain and nervous system have fully developed, their range of resiliency drastically narrows. In addition to the normal challenges of childhood, meeting later developmental tasks becomes that much more difficult. Being stuck in freeze-dissociation, these individuals have less access to healthy aggression, including the fight–flight response, and their capacity for social engagement is strongly impaired, leaving them much more vulnerable and less able to cope with later trauma and the challenges of life.

The Adult Experience

Adults who have experienced early trauma are engaged in a lifelong struggle to manage their high levels of arousal. They struggle with dissociative responses that disconnect them from their body, with the

vulnerability of ruptured boundaries, and with the dysregulation that accompanies such struggles. Individuals with less obvious symptoms may not consciously realize that they experience a diminished

capacity for joy, expansion, and intimate relationship; if they are aware of their difficulties, they usually do not understand their source. Individuals with the Connection Survival Style are often relieved to learn that their difficult symptoms have a common thread, what we call an organizing principle. Their struggle with high levels of anxiety, psychological and physiological problems, chronic low self-esteem, shame, and dissociation all constellate around the organizing principle of connection—both the desire for connection and the fear of connection.

When there is early trauma, varying degrees of predictable symptoms are commonly present. It is important to keep in mind that these symptoms usually occur simultaneously, loop back on each other, and continuously reinforce one another.

• Self-Image and Self-Esteem. Individuals traumatized in the Connection stage experience themselves as outsiders, disconnected from themselves and other human beings. Not able to see that the traumatic experiences that shaped their identity are due to environmental failures that were beyond their control, individuals with the Connection Survival style view themselves as the source of the pain they feel.

• The Need to Isolate. Because of the breach in their energetic boundaries, individuals with the Connection Survival Style use interpersonal distance to feel safe. They develop life strategies to minimize contact with other human beings.

• Nameless Dread. The internal experience of adults traumatized in the Connection stage is one of constant underlying dread and terror characterized in NARM as nameless dread. Their nervous system has remained in a continual sympathetically dominant global high arousal and it is this arousal that drives and reinforces their profound and persistent feeling of threat.

• A Designated Issue. A named and identified threat is better than nameless dread. Not realizing that the danger that they once experienced in their environment is now being carried forward as high arousal in their nervous system, the tendency is to project onto the current environment what has become an ongoing internal state. Once the dread has been named, it becomes what we call the designated issue. The designated issue can be fear of death, a phobia, real or perceived physical deficiencies such as overweight or other perceived “defects”, as well as real or perceived psychological or cognitive deficiencies such as dyslexia or not feeling smart enough. Designated issues, whether or not they have a basis in physical reality, come to dominate a person’s life, covering the deeper distress and masking the underlying core disconnection.

• Shame and Self-Hatred. Infants who experience early trauma of any kind experience the early environmental failure as if there were something wrong with them. Later cognitions such as “There is something basically wrong with me” or “I am bad” are built upon the early somatic sensation: “I feel bad.”

• Overwhelm. People with significantly compromised energetic boundaries describe themselves as feeling raw, sometimes without a skin. Compromised energetic boundaries lead to the feeling of

being flooded by environmental stimuli and particularly by human contact.

• Environmental Sensitivities. Intact energetic boundaries function to filter environmental stimuli. Inadequate or compromised boundaries, on the other hand, allow for an extreme sensitivity to external stimuli: human contact, sounds, light, touch, toxins, allergens, smells, and even electromagnetic activity.

• A Sense of Meaninglessness. A common refrain from individuals with the Connection Survival Style is “Life has no meaning” or “What’s the point?” Searching for meaning, for the why of existence, is one of the primary coping mechanisms used for managing their sense of disconnection and despair.

Dissociation: Bearing the Unbearable

When trauma is early or severe, some individuals completely disconnect by numbing all sensation and emotion. Disconnection from the bodily self, emotions, and other people is traditionally called dissociation. By dissociating, that is, by keeping threat from overwhelming consciousness, a traumatized individual can continue to function. When individuals are dissociated, they have little or no awareness that they are dissociated: they only become aware of their dissociation as they come out of it. Compassionate understanding for the pain and fear that drives the dissociative process is critical to healing the Connection dynamic. Just as a coyote with its leg caught in a trap chews it off in order to escape, in attempting to manage early trauma, the organism fragments, sacrificing unity in order to save itself. Disconnection sets up a pernicious cycle: To manage early trauma, children disconnect from their bodies, emotions, and aggression, foreclosing their vitality and aliveness. In addition, they also disconnect from other people. This disconnection, though life saving, produces more distress because they feel exiled from self and others. Seeing other people live in what one client called “the circle of love” and the distress of feeling “on the outside looking in” heighten both shame and alienation. [/quote]

The rest of the article can be read here _http://cellularbalance.com/Articles/Working_with_Developmental_Trauma.pdf

I can relate to much of what is written above- when I was reading it I felt like a light bulb just went on. Can't wait to read the book in full.