Super-chilled thunderstorm unlike any other ever detected

By Brian Lada, AccuWeather meteorologist and staff writer

Updated Apr. 1, 2021 5:28 PM CEST

The cluster of particularly cold brightness temperatures is slightly to the left of the image center. (Image/NOAA/VIIRS/S.Proud/UniOxford)

When people think of a thunderstorm, towering clouds on a warm and humid summer day may come to mind, but one thunderstorm tracked by forecasters over the Pacific Ocean several years ago set a record for the extremely cold conditions that it generated.

A new study published in American Geophysical Union examined a particularly strong thunderstorm that rumbled

over the Pacific Ocean well northeast of Australia on Dec. 29, 2018, a storm that has now gone down in the record books.

The record-setting storm was spotted by the NOAA-20 satellite, one of the most advanced weather satellites in NOAA’s fleet that launched just one year prior to the storm’s development.

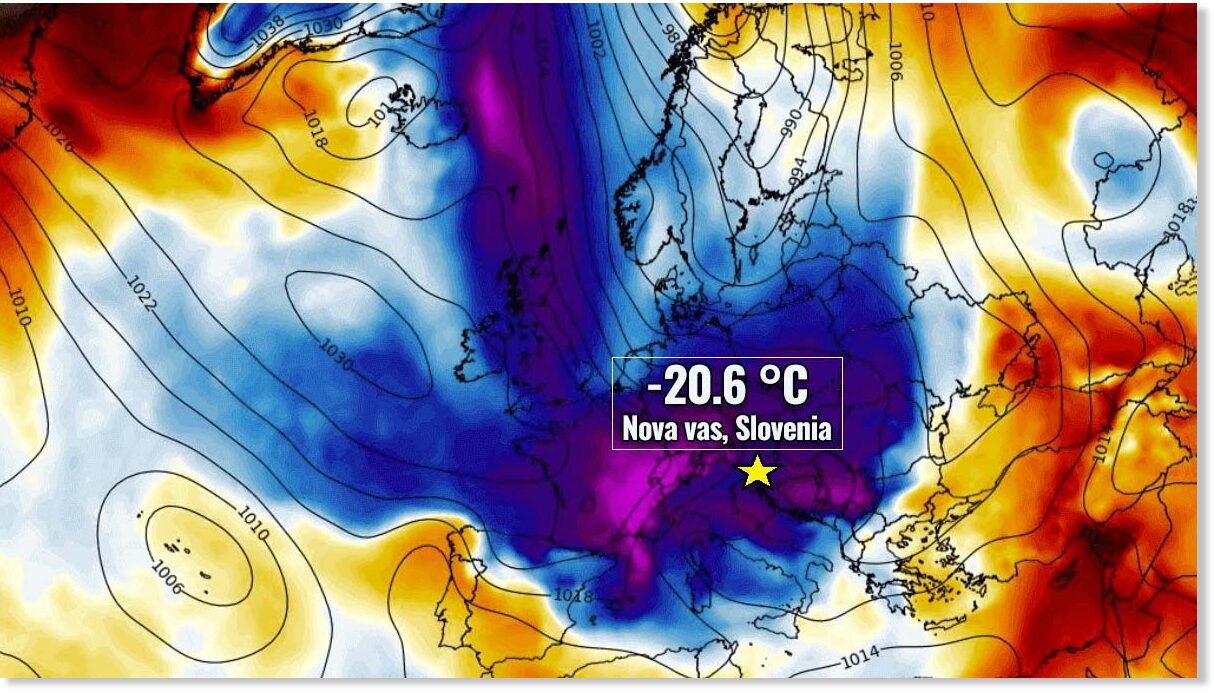

The lowest temperature detected in the clouds above the strongest part of the storm was so low that it was almost literally off the charts -- coming in at around minus 111.2 degrees Celsius, or a bitterly cold 168.1 degrees below zero Fahrenheit.

This “

extremely cold temperature that is, to our knowledge, the coldest recorded by satellite,” the authors of the study said. Previously, the lowest temperatures recorded in the cloud tops of storms anywhere around the globe ranged between 162 and 157 degrees below zero F.

The astonishingly low temperature was measured from space with the use of infrared sensors on the NOAA-20 satellite, a system that can accurately tell what the temperature is inside the clouds within Earth's atmosphere.

The driving feature behind every thunderstorm is the updraft, the column of rising air that gradually gets colder as it climbs higher and higher in the atmosphere.

When the rising column of air reaches the tropopause, the top of the lowest section of the atmosphere, the clouds typically fan out and spread outward. This is called an anvil cloud due to its resemblance to the tool used by blacksmiths.

In a stronger storm, like the one that was observed on Dec. 29, 2018, part of the storm clouds can poke through the tropopause and break into the next layer of the atmosphere, the stratosphere. This feature is called an ‘overshooting top’ and is the part of the storm where the record-breaking temperature was detected.

This image of a typical cumulonimbus cloud "anvil" was taken by the Expedition 16 crew on the International Space Station. The signature cauliflower shape of an overshooting top can be seen on the right region of the anvil cloud top. (Image/NASA)

The incredibly low temperature was not only due to the storm, but the overall state of the atmosphere that day.

On Dec. 29, 2018, the atmosphere around the tropopause was abnormally cold before the thunderstorm started to brew.

“Storm activity on this day was typical for the time of year, implying that the cold cloud top temperatures were primarily driven by the exceptionally cold tropopause rather than the unique properties of a given convective storm,“ the authors of the study explained.

What makes this thunderstorm even more impressive is the fact that when the NOAA-20 satellite passed over the storm, it was not at its peak strength.

The weather satellite is in polar orbit around the Earth, a type of orbit that allows the satellite to gather data about any given point on the planet two times a day. This is different than the GOES-East weather satellite which is in geosynchronous orbit, a type of orbit that allows a satellite to consistently take observations of the same region of the globe around the clock.

Because of this, the NOAA-20 satellite did not record the temperature of the cloud tops when they were at their coldest.

This new record, while impressive, may not stand for long, the researchers said.

“We found that these really cold temperatures seem to be becoming more common – with the same number of extremely cold temperatures in the last three years as in the 13 years before that,” said Dr. Simon Proud of the U.K.’s National Centre for Earth Observation.

Scientists think that the next record will likely happen over the same area of the Pacific Ocean where this record-setting storm took shape near the tail end of 2018. That is due in part to increasing sea-surface temperatures creating a more favorable environment for storm development along with

changing conditions higher in the atmosphere.