The year without a summer

In the spring of 1815, things were looking up for Canada.

Local Canadian militia, along with British forces and their Indigenous allies, had just thwarted an American invasion in the

War of 1812. Casualties aside—York (now Toronto) was briefly captured and Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) was burned down—the Canadians stood their ground. Lower Canada (present-day Quebec) had a population of about

335,000 people, while Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) had 95,000. Newfoundland, meanwhile, was home to a further 52,000 people.

For the first time, these Canadians—many of whom were newly-arrived immigrants with no connection to the Crown—started to feel like

Canadians.

Sixteen-thousand kilometres away, however, trouble was brewing.

The largest volcanic eruption in 2,000 years

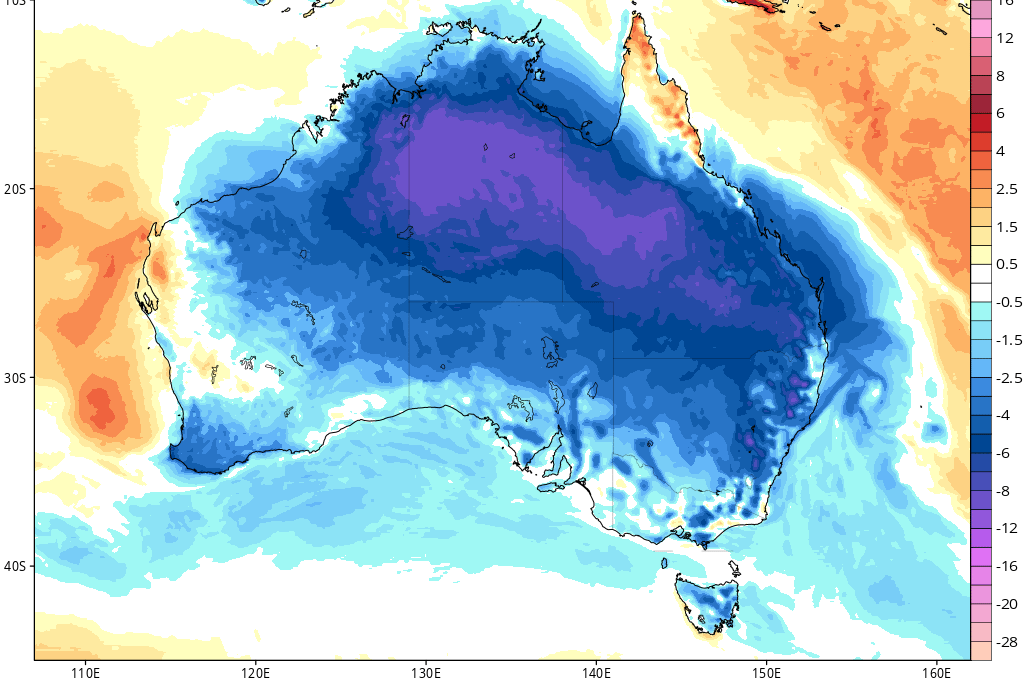

On April 5, 1815, Mount Tambora, a volcano on the island of Sumbawa in the Indonesian archipelago, suddenly erupted. Five days later, Tambora erupted once again, this time releasing 100 cubic kilometres of molten rock—and ash clouds that covered an area the size of Australia—into the sky.

Nearly 12,000 people living near Mount Tambora died—the victims of falling rocks and fast-moving gas currents. Over the next several months, an estimated 80,000 more would perish from starvation, contaminated drinking water, or respiratory infections from the ash that still remained in the atmosphere.

Scientists now know that Mount Tambora is the largest volcanic eruption of the last 2,000 years. In order to “rate” a volcano, today’s researchers use the Volcanic Explosivity Index: a system that uses whole numbers from zero to eight to measure the amount of ash, dust and sulphur a volcano throws into the atmosphere.

Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull volcano, which erupted in 2010 and

delayed air travel in Europe for six days, rates a mere four on the Volcanic Explosivity Index. The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Skamania County, Washington, is considered a five. Krakatoa, which erupted in 1883 and is also located in Indonesia, has been deemed a six.

Mount Tambora is the only stratovolcano (a volcano composed of alternating layers of lava and ash) to ever receive a score of seven.

Along with ash particles, the eruption also released 100-million tonnes of sulfuric acid into the stratosphere, writes historian William K. Klingaman and meteorologist Nicholas P. Klingaman in the book

The Year Without Summer. Over the next 12 months, this aerosol cloud spread around the world, cooling temperatures by drastically reducing the amount of solar energy that was able to reach Earth.

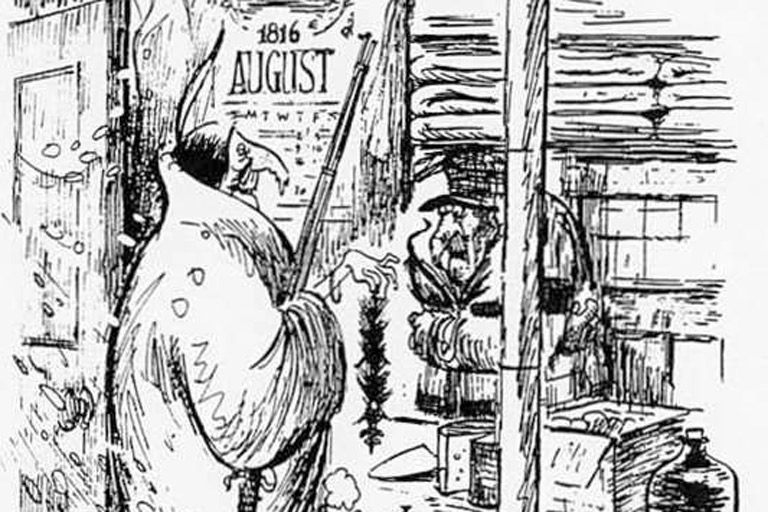

A summer of starvation and misery

It took a full year after the eruption for the shockwaves to reach Canada. On April 12, 1816, it began snowing in Quebec City—and it didn’t stop. A news report from April 18 wrote, “The country has all the appearance of the middle of winter, the depth of snow being still between three and four feet. We understand that in many parishes the cattle are already suffering from a scarcity of forage.”

By June, the noontime temperature in central Ontario was just one below zero. In the Quebec countryside, newly-shorn sheep began dying from the cold. The

Montreal Herald, meanwhile, urged readers to plant as many potatoes as possible in case the summer’s wheat crops failed completely.

Out west in Brandon, Manitoba, Peter Fidler of the Hudson’s Bay Company

witnessed a cold spell that began on June 5. “A very sharp frost at night… killed all the barley, wheat, oats and garden stuff above the ground except lettuce and onions,” he wrote. “The oak leaves are coming out as if they are singed by fire and dead.”

Cold fronts continued to sweep through Lower Canada in July. By then, growing season was three weeks behind. To avoid famine, the governor of Lower Canada banned the export of wheat, flour, beans and barley until September. At the same time, he opened Canadian harbours to grain imports from the U.S.—free of tariffs.

His efforts, however, were in vain. By September, Lower Canada was destitute. Up to four-fifths of the region’s hay crops were ruined, while the frost left the province with a small wheat harvest and an even smaller supply of oats. Farmers were forced to sell their dairy cows to buy bread, while others survived on a diet of wild herbs.

Disaster for the rest of the world

Eastern Canada was far from the only region affected that summer, however.

Summer frosts also devastated much of the eastern United States, from New England to Virginia. Failing crops and rising bread prices led many hungry settlers to leave for areas in the Midwest, particularly modern-day Indiana and Illinois.

Across the Atlantic, the citizens of Germany and France struggled with surging food prices. In the Netherlands, rainstorms destroyed so much hay and grain crops that farmers, fearing their livestock would die of starvation, began slaughtering them. Ireland, meanwhile, faced famine as the region’s wheat, oat and potato harvests failed.

India was ravaged by several late-season downpours. As harvests failed, a combination of famine, mass migration and crowded communities led to the world’s first cholera pandemic. By the winter of 1816, the disease broke out of northeastern Bengal—where it killed 10,000 people in two weeks—and spread across Nepal, Thailand, the Philippines, China and Japan.

The aftermath

While Mount Tambora’s toxic aerosol cloud had its most catastrophic impact in the summer of 1816,

weather patterns around the world continued to be affected for at least another two years.

The stratovolcano erupted again 1819—this time, it registered only a two on the Volcanic Explosivity Index. It erupted twice more between 1847 and 1913, and again in 1967. A string of earthquakes on Sumbawa in 2011 led the Indonesian government to fear another eruption, but experts believe no explosion from Mount Tambora would again approach the magnitude of 1815-16.

Now that you know the story of the year without a summer, find out what it was like on the

coldest day in Canadian history.

www.bloomberg.com

www.bloomberg.com