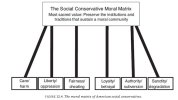

Moral Foundations Theory says that there are (at least) six psychological systems that comprise the universal foundations of the world’s many moral matrices. The various moralities found on the political left tend to rest most strongly on the Care/ harm and Liberty/ oppression foundations. These two foundations support ideals of social justice, which emphasize compassion for the poor and a struggle for political equality among the subgroups that comprise society. Social justice movements emphasize solidarity— they call for people to come together to fight the oppression of bullying, domineering elites.

Everyone— left, right, and center— cares about Care/ harm, but liberals care more. Across many scales, surveys, and political controversies, liberals turn out to be more disturbed by signs of violence and suffering, compared to conservatives and especially to libertarians.

Everyone— left, right, and center— cares about Liberty/ oppression, but each political faction cares in a different way. In the contemporary United States, liberals are most concerned about the rights of certain vulnerable groups (e.g., racial minorities, children, animals), and they look to government to defend the weak against oppression by the strong. Conservatives, in contrast, hold more traditional ideas of liberty as the right to be left alone, and they often resent liberal programs that use government to infringe on their liberties in order to protect the groups that liberals care most about. For example, small business owners overwhelmingly support the Republican Party in part because they resent the government telling them how to run their businesses under its banner of protecting workers, minorities, consumers, and the environment. This helps explain why libertarians have sided with the Republican Party in recent decades. Libertarians care about liberty almost to the exclusion of all other concerns, and their conception of liberty is the same as that of the Republicans: it is the right to be left alone, free from government interference.

The Fairness/ cheating foundation is about proportionality and the law of karma. It is about making sure that people get what they deserve, and do not get things they do not deserve. Everyone— left, right, and center— cares about proportionality; everyone gets angry when people take more than they deserve. But conservatives care more, and they rely on the Fairness foundation more heavily— once fairness is restricted to proportionality. For example, how relevant is it to your morality whether “everyone is pulling their own weight”? Do you agree that “employees who work the hardest should be paid the most”? Liberals don’t reject these items, but they are ambivalent. Conservatives, in contrast, endorse items such as these enthusiastically.

Liberals may think that they own the concept of karma because of its New Age associations, but a morality based on compassion and concerns about oppression forces you to violate karma (proportionality) in many ways. Conservatives, for example, think it’s self-evident that responses to crime should be based on proportionality, as shown in slogans such as “Do the crime, do the time,” and “Three strikes and you’re out.” Yet liberals are often uncomfortable with the negative side of karma— retribution...