We should here note that Rudolf Steiner in 1911 wrote a book called The Spiritual Guidance of Mankind in which he claims that, by clairvoyant insight, he was able to reconstruct the history of the Zoroastrian influence in human life over a period of eight thousand years, or from the origins of the Aryan culture. As Gurdjieff makes several references to anthroposophy in Beelzebub’s Tales, we may assume that he was aware of the importance that Steiner attached to the Zoroastrian traditions. He invariably refers to anthroposophy in slighting terms as an aberration of the same order as theosophy and spiritualism. It does not, by any means, follow that he rejected all the conclusions reached by Rudolf Steiner. From his attitude in conversation, I would surmise that he objected to the uncritical acceptance of statements which were unsupported by historical evidence.

It has been suggested that the 'Cosmic Individual Incarnated from Above', who is called Ashiata Shiemash in Beelzebub’s Tales1 is intended for Zarathustra (Zoroaster). Gurdjieff certainly spoke of Ashiata Shiemash in three different ways. He was an historical character who had really lived in Asia thousands of years ago. He was also the image of the prophet of the New Epoch who is still to come, and he was also Gurdjieff himself. He said more than once: "I am Ashiata Shiemash". It has also been asserted that these chapters are purely allegorical and refer to no historical situation past, present or future. In my opinion, all four interpretations are valid and we should therefore examine the first to see if it helps us with the search for an 'Inner Circle'.

After his enlightenment, Ashiata is said to have gone to "the capital city Djoolfapal of the country then called Kurlandtech which was situated in the middle of the continent of Asia", If this refers to Zarathustra's journey in his thirtieth year, after receiving enlightenment, the city must be Balkh where Kave Gushtaspa was king. Here Zarathustra found two men, counsellors of the king, Jamaspa and Frashaostra who were seeking for wisdom. He enlightened them and initiated the king. There is a remarkable verse in the Avesta (fifth Gatha, verse 16) which says: "The leadership of the Maga mysteries has been bestowed on Kave Gushtaspa. At the same time he has been initiated into the path of Vohu Manah by inner-vision. This is the way that Ahura Mazda has decreed according to Asha."

In later Persian sacred literature, Asha becomes Ashtvahasht, which is strangely suggestive of Ashiata Shiemash. According to the legend, Kave Gushtaspa placed himself entirely under the direction of Zarathustra and this inaugurated the reign of the Good Law.

It is obviously possible that Gurdjieff has all this in mind, but he left no clear indication. The name Ashiata Shiemash can be derived from the Turkish word Ash, meaning food, and the words iat and iem which refer to eating. According to this interpretation, Ashiata Shiemash personifies the principle of reciprocal feeding.1 This is very interesting because of the conclusion I reach on other grounds that the principle has a Zoroastrian origin. (See Chapter 8 below.)

The nearest Gurdjieff comes anywhere to describing a society that influenced history is in the "Organization for Man's Existence Created by the Very Saintly Ashiata Shiemash"2 The society, called the Brotherhood Heechtvori, developed from the society he found in Djoolfapal (Balkh?). He interprets the name to mean 'only he will be called and will become the Son of God who acquires in himself conscience.' This society was not occupied with social organization and reform nor with the exercise of power. It was a training establishment to which people went to have their 'reason enlightened'; first as to the real presence of conscience in man; and, secondly, as to the means whereby it can be 'manifested in order that a man may respond to the real sense and aim of his existence'.1 The external, social consequences of the training are depicted as deep and far-reaching. New kinds of relationship came into being, men looked for guidance rather than for authority. Social and political conflicts disappeared. This was not the result of reform or reorganization, but solely of a change in people. I think Gurdjieff uses the story of Ashiata Shiemash not only to underline the central significance of conscience in his message to humanity, but also to suggest that he has no confidence in any kind of occult 'action at a distance'. People are to be helped by actions that they can understand and, in due course, produce for themselves.

Zoroaster was associated in the minds of Central Asian communities with the struggle that endured for thousands of years between the Turanian nomads and the Aryan settlers. The 'Avestan Gathas' often identify the Turanians with the evil spirits in spite of the fact that more than one Turanian prince became a follower of Zoroaster. Gurdjieff's society, 'The Earth is Equally Free for All', was to adopt the ancient Turanian language and combine it with the Aryan religion of the Parsis and establish its main centre in Ferghana. The only possible interpretation of such a combination is that it refers to a society that was on such a high level that the conflicts that divide religions and peoples did not touch it. No higher society could be imagined than the 'Assembly-of-All-theLiving-Saints-of-the-Earth'.

The connection between this society and the Sarmān Brotherhood is given both by the name and by the location, first in Mosul and then in Bokhara. In Meetings with Remarkable Men, Gurdjieff describes how he and his Armenian friend, Pogossian, found ancient Armenian texts, including the book Merkhavat, that referred to the 'Sarmoung' society as a famous esoteric school that according to tradition had been founded in Babylon as far back as 2500 BC and which was known to have existed in Mesopotamia up to the sixth or seventh century of the Christian era. The school was said to have possessed great knowledge containing the key to many secret mysteries.2 The date of 2500 BC would put the founding of this school several centuries before the time of Hammurabi, the greatest lawgiver of antiquity, but it is not an impossible one. It is an interesting date, because it coincides with the migration that brought together a Semitic people, the Akkadians, and the older Indo-European race of the Sumerians. It is quite plausible to suppose that a school of wisdom could then have been established that guided the course of events towards the wonderful achievements of Sargon I and Hammurabi. If such a school existed, it would have abandoned Babylon after the time of Darius II, about 400 BC, and could very well have moved north into the upper valley of the Tigris where the Parthians were about to begin their long period of dominance in the mountains of Kurdistan and the Caucasus. The Parthians brought with them a pure Zoroastrian tradition. The Armenian hegemony bridged the gap until the arrival of the Seljuks at the end of the first millennium AD. This was a time when caravan routes in all directions passed through the upper valleys and it was possible to collect and concentrate traditions from China to Egypt.

This leads us to the next phase of Gurdjieff 's contact with the Sarmān Brotherhood. He reports that in the course of a sojourn at Ani, one of the capitals of the Bagratid Armenian kingdom, he and Pogossian found a collection of letters written on parchment sometime in the seventh century AD, one of which contained a reference to the Sarmān Brotherhood as having one of their main centres near the town of Siranush. They had migrated to the north-east and settled in the valley of Izrumin, three days' journey from 'Nivssi'. Gurdjieff goes on to say that their further researches led them to identify Nivssi with Mosul which is already connected with the Society of the Enlightened. By the date mentioned, Nineveh had ceased to be inhabited but Nimrud, the ancient capital of the Assyrian king, Assurbanipal, was still a great trading centre on account of its location at a point where the Tigris begins to be navigable all the year round.

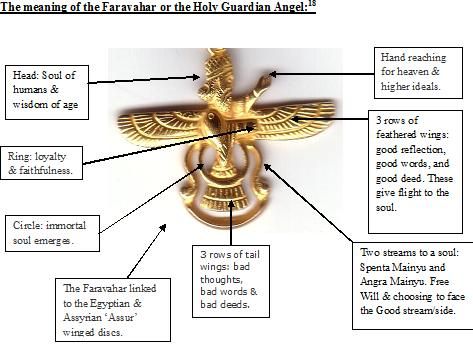

Three days' journey by camel from Nimrud through almost desert country leads to a valley green with trees, in the midst of which is Sheikh Adi - the chief sanctuary of the Yezidi Brotherhood. Now the Yezidis are certainly inheritors of the old Zoroastrian tradition and Gurdjieff specifically refers to them among the groups of Assyrians he found in the region surrounding Mosul which was the heart of the old Assyrian Empire. I visited Sheikh Adi in 1952 and was convinced that the Yezidis possessed secrets unsuspected by orientalists who classify their faith as a relic of paganism. Their connection with the Mithraic tradition is generally accepted because of their chief festival of the white bull which takes place at Sheikh Adi in October every year. They are even more directly descended from the followers of Manes whose influence spread very widely all through Asia in the third and fourth centuries of our era, only two hundred years before the Sarmān Brotherhood was reported as having its headquarters at Izrumin.

It seems probable that a very strong tradition did exist in Chaldaea from very early times. Gurdjieff, both in his writings and in his conversations with his pupils, constantly referred to this ancient tradition. We can assume that, during the great upheavals of history, the guardians of the tradition responded in the way described in the last chapter: dividing into three branches, one of which migrated, one was assimilated into the new regime and the third went into hiding.

At the time of the Muslim conquests in the seventh and eighth centuries, groups like the Yezidis and the Ahl-i-Haqq were formed. They presented more or less acceptable doctrines to the Arabs, who could not understand the subtleties of Persian spirituality. There was relatively little forced conversion of Nestorian Christians, whose beliefs were substantially compatible with the teaching of the Qur'an. Our main concern is with the third group who withdrew into Central Asia. This is the group that corresponds to Gurdjieff 's account of the Sarmān Brotherhood.

Gurdjieff himself makes no attempt to explain the migration. In his adventures with Pogossian, the 'Sarmoung' Brotherhood is located in Chaldaea. In the story of Prince Yuri Lubovedsky,1 they have moved to Central Asia, twenty days' journey from Kabul and twelve days' journey from Bokhara. He refers to the valleys of the Pyandje and the Syr Darya, which suggest an area in the mountains south-east of Tashkent. He discloses at the end of this chapter that this

1 Meetings with Remarkable Men, Chapter VII, p. 149.

particular brotherhood had another centre in the 'Olman' monastery on the northern slopes of the Himalayas. The word 'Olman' is a link with Olmantaboor who was the head of the 'Assembly-of-the-Enlightened'. The northern slopes of the Himalayas connect with the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers.

We must now closely examine the slender clues that Gurdjieff has left us to reconstruct the teaching he found at the monastery between the Amu and Syr Darya rivers, and described both directly and obliquely in Meetings with Remarkable Men.