Perhaps is related or ...due to thisgoyacobol said:MusicMan said:Rare deep earthquakes happening, both sides of the Pacific. Could be something brewing..

(Watch from 10:42. Dutchsinse got all excited, and forgot to turn off a graphic at the beginning, so he started over. The video date was indicated as 27th. but was actually the 25th.)

3/27/18 3pm earthquake update dutchsinse - deep M5.1 NZ, M6.6 Indonesia

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oZvmAL_MwTM

I think you are right MusicMan those 750km deep ones add to the magnitude according to dutchsinse by 1.5 bringing a 5.1 up to 6.6. They don't just go away but spread through the plates resulting in lower magnitude ones much farther away.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Earthquakes around the world

- Thread starter pescado

- Start date

angelburst29

The Living Force

A 6.4 magnitude earthquake struck off eastern Indonesia in the early hours of Monday, triggering a brief tsunami alert that was swiftly lifted, according to seismic monitoring organizations.

6.4 magnitude quake off eastern Indonesia, tsunami alert lifted Sunday 25 March 2018

http://www.arabnews.com/node/1273601/world

The quake struck deep at some 171 kilometers (106 miles) below the surface of the earth in the Banda Sea the US Geological Survey said.

A tsunami alert was initially triggered by the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System (IOTWMS).

However IOTWMS followed up with a second bulletin that said there was “no threat to countries in the Indian Ocean.”

The quake’s epicenter was located in a sparsely inhabited part of the Banda Sea, 222 kilometers northwest from Indonesia’s Tanimbar Islands and 380 kilometers from Ambon, the capital of Maluku province.

A similar 6.1 magnitude quake hit close to Monday’s epicenter on 26 February and caused no damage.

Indonesia sits on the so-called Pacific Ring of Fire, a seismic activity hotspot. It is frequently hit by quakes, most of them harmless.

However the archipelago remains acutely alert to tremors that might trigger tsunamis.

In 2004 a devstating tsunami triggered by a magnitude 9.3 undersea earthquake off the coast of Sumatra killed 220,000 people in countries around the Indian Ocean, including 168,000 in Indonesia.

Magnitude 7.0 Earthquake Hits Waters Off Papua New Guinea - USGS 26.03.2018

https://sputniknews.com/latam/201803261062902530-quake-guinea-usgs/

The tremor was registered at 09:51 GMT with the epicenter located 151 kilometers (94 miles) east of the town of Kimbe of the Papua New Guinean West New Britain province, located on the island of New Britain, according to the USGS.

The geological survey added that the epicenter of the quake was at a depth of 10 kilometers.

There are no reports about victims or damage caused by the earthquake.

6.4 magnitude quake off eastern Indonesia, tsunami alert lifted Sunday 25 March 2018

http://www.arabnews.com/node/1273601/world

The quake struck deep at some 171 kilometers (106 miles) below the surface of the earth in the Banda Sea the US Geological Survey said.

A tsunami alert was initially triggered by the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System (IOTWMS).

However IOTWMS followed up with a second bulletin that said there was “no threat to countries in the Indian Ocean.”

The quake’s epicenter was located in a sparsely inhabited part of the Banda Sea, 222 kilometers northwest from Indonesia’s Tanimbar Islands and 380 kilometers from Ambon, the capital of Maluku province.

A similar 6.1 magnitude quake hit close to Monday’s epicenter on 26 February and caused no damage.

Indonesia sits on the so-called Pacific Ring of Fire, a seismic activity hotspot. It is frequently hit by quakes, most of them harmless.

However the archipelago remains acutely alert to tremors that might trigger tsunamis.

In 2004 a devstating tsunami triggered by a magnitude 9.3 undersea earthquake off the coast of Sumatra killed 220,000 people in countries around the Indian Ocean, including 168,000 in Indonesia.

A magnitude 7.0 earthquake hit waters near Papua New Guinea on Monday, the US Geological Survey (USGS) said.

Magnitude 7.0 Earthquake Hits Waters Off Papua New Guinea - USGS 26.03.2018

https://sputniknews.com/latam/201803261062902530-quake-guinea-usgs/

The tremor was registered at 09:51 GMT with the epicenter located 151 kilometers (94 miles) east of the town of Kimbe of the Papua New Guinean West New Britain province, located on the island of New Britain, according to the USGS.

The geological survey added that the epicenter of the quake was at a depth of 10 kilometers.

There are no reports about victims or damage caused by the earthquake.

All this earthquake activity reminds me of the Cs saying that when the earth slows down its rotation, everything "opens up". They also made a remark about a lot of volcanoes going off at once at some point.

We do live in interesting times!

We do live in interesting times!

Magnitude 7.2 quake off Papua New Guinea triggers tsunami threat message

Published time: 29 Mar, 2018 22:07

https://www.rt.com/news/422735-papua-new-guinea-quake-tsunami/

M 7.0 - NEW BRITAIN REGION, P.N.G. - 2018-03-29 21:25:39 UTC

https://www.emsc-csem.org/Earthquake/earthquake.php?id=656861#summary

Forecast

_http://www.ditrianum.org/

updated 23 March 2018, 6:43 UTC

Earthquake Forecast 25 March - 2 April 2018 / 5:49

Published on Mar 25, 2018

_https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHU0XfgUQqs

Published time: 29 Mar, 2018 22:07

https://www.rt.com/news/422735-papua-new-guinea-quake-tsunami/

A magnitude 6.9 earthquake has hit off the coast of Papua New Guinea, triggering a tsunami threat message from the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center.

A powerful earthquake struck near the coast of Papua New Guinea, some 144 kilometers from the town of Kimbe in the province of West New Britain, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS). The quake's magnitude has been revised to 6.9 from the earlier estimate of 7.2. The epicenter was 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) deep.

M 7.0 - NEW BRITAIN REGION, P.N.G. - 2018-03-29 21:25:39 UTC

https://www.emsc-csem.org/Earthquake/earthquake.php?id=656861#summary

Forecast

_http://www.ditrianum.org/

updated 23 March 2018, 6:43 UTC

Planetary alignments on the 23rd and 25th may trigger seismic activity over magnitude 6 between the 23rd and 27th. From the 29th into the first week of April planetary geometry becomes more critical with the potential of a high 6 to 7 magnitude earthquake.

Earthquake Forecast 25 March - 2 April 2018 / 5:49

Published on Mar 25, 2018

_https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHU0XfgUQqs

Ingenues building ideas happening in Oaxaca, Mexico.

Mexico: NGO Builds Earthquake-Resistant Clay Homes in Oaxaca / 0:33

Sputnik Published on Mar 30, 2018

Earthquake survivors in Mexico rebuild from scratch with recycled materials / 2:34

Published on Mar 30, 2018

Mexico: NGO Builds Earthquake-Resistant Clay Homes in Oaxaca / 0:33

Sputnik Published on Mar 30, 2018

Teresa Guzman, who lost her home in the September temblors, will be the first person to benefit from the anti-earthquake structure created by the NGO Red Global MX.

Earthquake survivors in Mexico rebuild from scratch with recycled materials / 2:34

Published on Mar 30, 2018

The fallout from last year’s September 19 earthquake in Mexico continues to reverberate around the country, as the worst-affected communities pick up the pieces. Yet one group of people have come across an efficient way to rebuild.

angelburst29

The Living Force

A magnitude 5.3 earthquake has hit western Iran, but there are no immediate reports of victims or damage, state television reported.

Magnitude 5.3 Quake Shakes Western Iran - Reports 01.04.2018

https://sputniknews.com/middleeast/201804011063114007-iran-earthquake-damage-victims/

According to the European-Mediterranean Seismological Center, the epicenter of the tremors was 98 km to the northwest of the Iranian city of Ilam and 170 km to the northeast of the Iraqi capital, Baghdad. The epicenter was at a depth of 52 km.

"Up to this moment,… we have not received any reports of casualties or damage," the head of the crisis management body in the affected province of Kermanshah, Iran, told state television.

Iran is situated on major fault lines and is prone to near-daily earthquakes.

A 7.2-magnitude earthquake in November rocked the Kurdish town of Sarpol-e-Zahab and killed 600 people.

In 2003, a 6.6-magnitude earthquake razed the historic city of Bam to the ground, killing 26,000 people.

Magnitude 5.3 Quake Shakes Western Iran - Reports 01.04.2018

https://sputniknews.com/middleeast/201804011063114007-iran-earthquake-damage-victims/

According to the European-Mediterranean Seismological Center, the epicenter of the tremors was 98 km to the northwest of the Iranian city of Ilam and 170 km to the northeast of the Iraqi capital, Baghdad. The epicenter was at a depth of 52 km.

"Up to this moment,… we have not received any reports of casualties or damage," the head of the crisis management body in the affected province of Kermanshah, Iran, told state television.

Iran is situated on major fault lines and is prone to near-daily earthquakes.

A 7.2-magnitude earthquake in November rocked the Kurdish town of Sarpol-e-Zahab and killed 600 people.

In 2003, a 6.6-magnitude earthquake razed the historic city of Bam to the ground, killing 26,000 people.

angelburst29

The Living Force

05.04.2018 - 5.9-Magnitude Quake strikes off Philippines

5.9-Magnitude Quake Strikes Off Philippines

A moderate 5.9-magnitude earthquake hit Thursday off the second largest Philippine island of Mindanao, the US Geological Survey reported.

The tremor was registered at 3:53 a.m. GMT around 45 kilometers (28 miles) southeast from the Tarragona municipality. The epicenter lied at the depth of 64.4 kilometers (40 miles).

There were no immediate reports of casualties or damage. No tsunami warnings were issued.

Previous year Philippines have been struck several times with earthquakes in April. On April 12th a 5.8-magnitude quake hit the southern Philippines north of the town of Osias, just before 5.3-magnitude another earthquake on April 23th, which occurred in the vicinity of the Tandag city in the northern part of Mindanao. Another earthquake struck Philippines on April 28th on Saturday morning near Mindanao.

5.9-Magnitude Quake Strikes Off Philippines

A moderate 5.9-magnitude earthquake hit Thursday off the second largest Philippine island of Mindanao, the US Geological Survey reported.

The tremor was registered at 3:53 a.m. GMT around 45 kilometers (28 miles) southeast from the Tarragona municipality. The epicenter lied at the depth of 64.4 kilometers (40 miles).

There were no immediate reports of casualties or damage. No tsunami warnings were issued.

Previous year Philippines have been struck several times with earthquakes in April. On April 12th a 5.8-magnitude quake hit the southern Philippines north of the town of Osias, just before 5.3-magnitude another earthquake on April 23th, which occurred in the vicinity of the Tandag city in the northern part of Mindanao. Another earthquake struck Philippines on April 28th on Saturday morning near Mindanao.

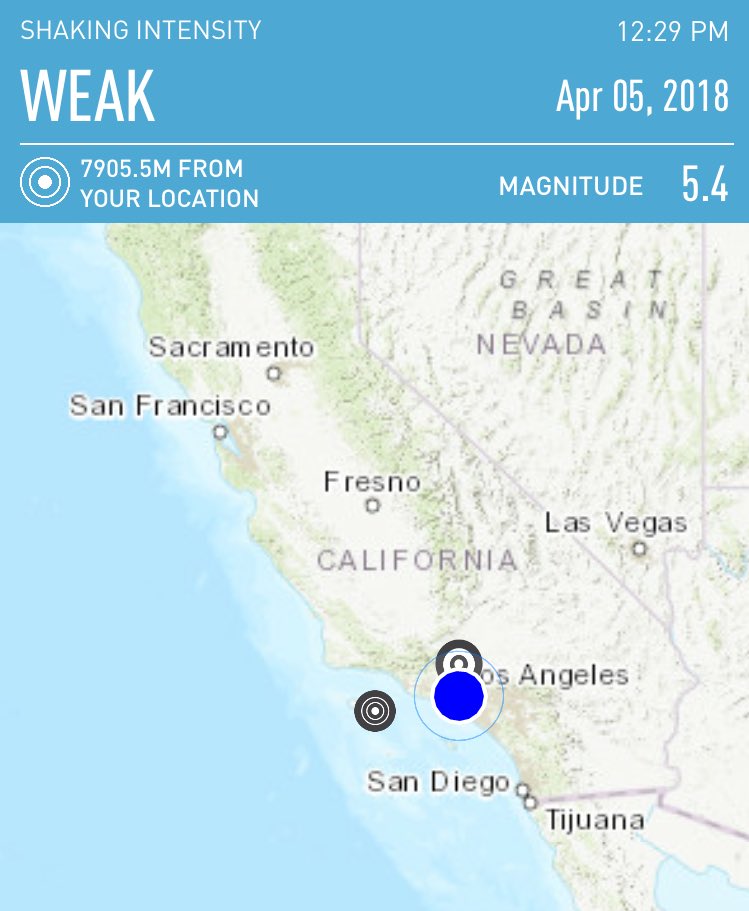

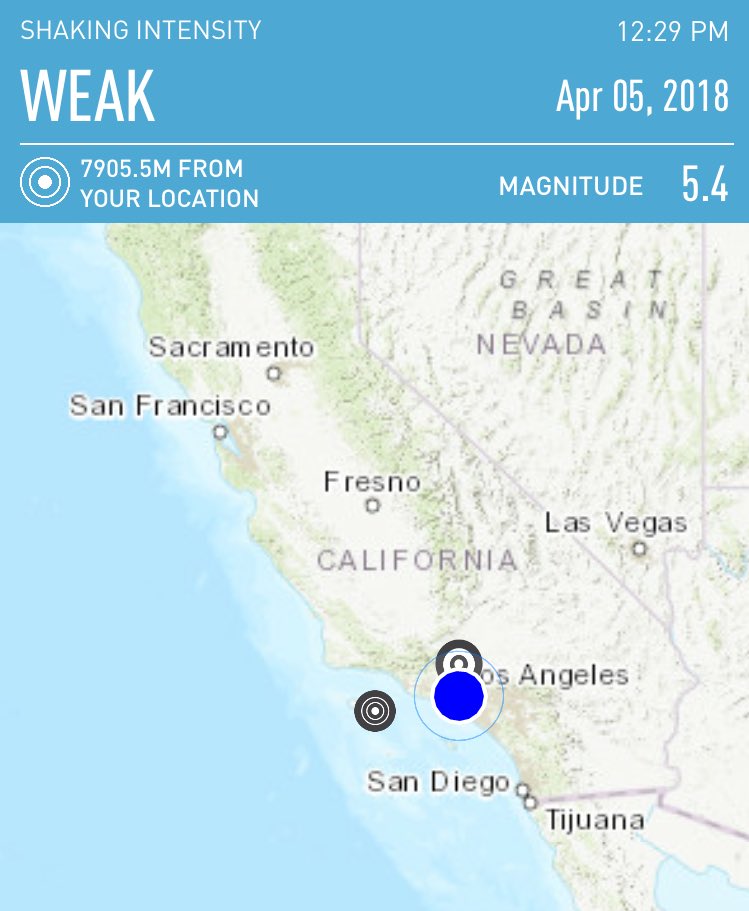

Magnitude 5.3 earthquake strikes near Channel Islands; no damage reported (Depth17 km)

Snip: Video (They are clueless as is there Science)

Published on Apr 5, 2018

Snip: Video (They are clueless as is there Science)

A magnitude 5.3 earthquake struck near the Channel Islands on Thursday afternoon, the U.S. Geological Survey said. The quake was the strongest in Southern California in several years.

The temblor occurred just before 12:30 p.m. and was centered south of Santa Cruz Island. It was felt as far away as Bakersfield, Palmdale and the city of Orange, according to witnesses and the USGS.

The Los Angeles Police Department said it had not received any reports of injuries or damage since the earthquake struck.

The Los Angeles Fire Department said it went into "earthquake mode" in which firefighters deploy and check all major areas of concern, such as freeway overpasses, large buildings and infrastructure for damage.

Potential for Large Earthquake 5-6 April 2018There is a 1-in-20 chance that Thursday's quake will lead to a larger one in the next few weeks, he said. But, more than likely, smaller aftershocks that may not even be felt will follow, he said.

The quake was too small and far away from the coast to trigger any tsunami concerns.

"It would never make a wave that you could see," he said

Published on Apr 5, 2018

With the Venus-Mercury-Jupiter alignment on the 3rd, the Moon lined up with Jupiter at the same time. This kind of planetary geometry can cause very large seismic activity from time to time on our planet, depending on the condition of Earth's crust.

Last edited:

angelburst29

The Living Force

07.04.2018 - Magnitude 6.3 Earthquake hits waters off Papua New Guinea - EMSC

Magnitude 6.3 Earthquake Hits Waters Off Papua New Guinea - EMSC

A magnitude 6.3 earthquake hit waters near Papua New Guinea on Saturday, the European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre (EMSC) said Saturday.

The tremor was registered at 05:48 GMT with the epicenter located 93 kilometers (57 miles) southwest of the town of Porgera of the Papua New Guinean Enga province, EMSC reported.

The geological survey added that the epicenter of the quake was at a depth of 40 kilometers. There are no reports about victims or damage caused by the earthquake.

Magnitude 6.3 Earthquake Hits Waters Off Papua New Guinea - EMSC

A magnitude 6.3 earthquake hit waters near Papua New Guinea on Saturday, the European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre (EMSC) said Saturday.

The tremor was registered at 05:48 GMT with the epicenter located 93 kilometers (57 miles) southwest of the town of Porgera of the Papua New Guinean Enga province, EMSC reported.

The geological survey added that the epicenter of the quake was at a depth of 40 kilometers. There are no reports about victims or damage caused by the earthquake.

angelburst29

The Living Force

April 09, 2018 - Strong 6.1 earthquake cracks streets in western Japan, injures 5

Strong earthquake cracks streets in western Japan, injures 5

TOKYO: A strong earthquake hit western Japan early Monday, cracking streets, cutting water and power to a number of homes and injuring five people.

The Meteorological Agency said the magnitude 6.1 quake struck 12 kilometers underground near Ohda city, about 800 kilometers west of Tokyo.

Five people sustained injuries, but most of them were minor and not life-threatening, the Fire and Disaster Management Agency said.

The quake also rattled nearby Izumo, home to one of Japan’s most important Shinto shrines. No damage was reported at the shrine.

The Fire and Disaster Management Agency said roads were cracked in some locations, while more than 1,000 households lost water supplies and dozens of homes were without electricity. Local officials said dozens of trains in the region were delayed or suspended.

There was no danger of a tsunami.

Strong earthquake cracks streets in western Japan, injures 5

TOKYO: A strong earthquake hit western Japan early Monday, cracking streets, cutting water and power to a number of homes and injuring five people.

The Meteorological Agency said the magnitude 6.1 quake struck 12 kilometers underground near Ohda city, about 800 kilometers west of Tokyo.

Five people sustained injuries, but most of them were minor and not life-threatening, the Fire and Disaster Management Agency said.

The quake also rattled nearby Izumo, home to one of Japan’s most important Shinto shrines. No damage was reported at the shrine.

The Fire and Disaster Management Agency said roads were cracked in some locations, while more than 1,000 households lost water supplies and dozens of homes were without electricity. Local officials said dozens of trains in the region were delayed or suspended.

There was no danger of a tsunami.

angelburst29

The Living Force

10.04.2018 - 6.2-Magnitude Earthquake shakes Chile - USGS (Video)

6.2-Magnitude Earthquake Shakes Chile - USGS

Chile is a part of the so-called Pacific Rim of Fire - a group of seismologically active territories surrounding the world's largest ocean and characterized by frequent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. One of the most significant quakes in Chile took place on February 27, 2010, registering 8.8 Richter scale.

A 6.2-magnitude earthquake rattled the coast of Chile on April 10, striking some 120 kilometers southwest of the port city of Coquimbo, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS). Chile's emergency service agency reports no damage has been detected so far. The country's navy said there is no tsunami risk.

Last April, a brief 7.1-magnitude quake was detected near Santiago, the country's capital, but didn't result in any significant damage or casualties. One of the most devastating earthquakes in Chile's recent history occurred on February 27, 2010. Some 525 people died and 25 went missing in the result of the quake and the tsunami that followed it. Richard Gross, one of the NASA scientists calculated that the 2010 Chilian earthquake actually affected the Earth's axis and shortened our day by about 1.26 microseconds.

6.2-Magnitude Earthquake Shakes Chile - USGS

Chile is a part of the so-called Pacific Rim of Fire - a group of seismologically active territories surrounding the world's largest ocean and characterized by frequent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. One of the most significant quakes in Chile took place on February 27, 2010, registering 8.8 Richter scale.

A 6.2-magnitude earthquake rattled the coast of Chile on April 10, striking some 120 kilometers southwest of the port city of Coquimbo, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS). Chile's emergency service agency reports no damage has been detected so far. The country's navy said there is no tsunami risk.

Last April, a brief 7.1-magnitude quake was detected near Santiago, the country's capital, but didn't result in any significant damage or casualties. One of the most devastating earthquakes in Chile's recent history occurred on February 27, 2010. Some 525 people died and 25 went missing in the result of the quake and the tsunami that followed it. Richard Gross, one of the NASA scientists calculated that the 2010 Chilian earthquake actually affected the Earth's axis and shortened our day by about 1.26 microseconds.

Moderate Earthquake Swarm Detected Below Kilauea Volcano Summit

HAWAII VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - Over 200 earthquakes occurred Wednesday at depths of 4.5 to 5.5 miles below Kīlauea's summit, scientists say.

(BIVN) – A moderate swarm of over 200 earthquakes occurred Wednesday below the summit of Kīlauea volcano.

The seismicity returned to its background rate at about 2:30 a.m. Thursday morning, scientists with the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory report.

The earthquakes were recorded at depths of 4.5 to 5.5 miles below Kīlauea’s summit, where an active lava lake is present within Halemaʻumaʻu Crater. The largest event in the sequence was a Magnitude 2.4, scientists say.

There was no change detected in deformation data due to the earthquake activity, USGS says. This morning, summit tiltmeters were recording small amounts of deflationary tilt, consistent with the deflationary phase of a summit DI event. The summit lava lake remains at a high level, and this morning was measured to be about 105 feet below the rim of the Overlook crater, slightly deeper than it was yesterday. Spattering was periodically visible from the Jaggar Museum yesterday.

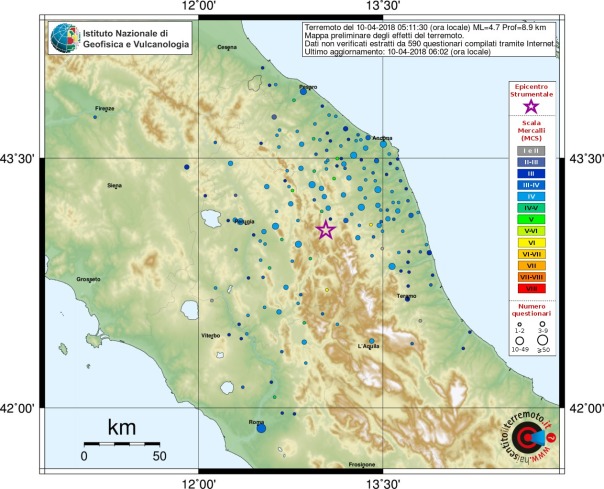

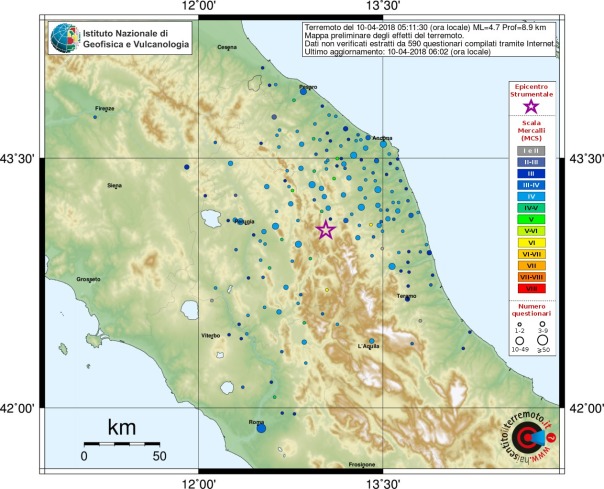

Terremoto di magnitudo 4.6 nel Maceratese. Danni, scuole chiuse e 20 sfollati a Pieve Torina

4.6 magnitude earthquake in the Maceratese area. Damages, closed schools and 20 displaced persons in Pieve Torina

10 aprile 2018 Snip: Pic's

The earthquake at 5.11 with epicenter 2 km from Muccia. No injuries, but so much fear.

The belfry of the Church of the '600 Santa Maria di Varano is damaged. Warned in the provinces of Macerata, Ancona, Pesaro, Umbria, part of Tuscany, Lazio, the Aquila area and Rome. Stramondo (Invg): "The earth trembles in the region because of the Adriatic plaque that creeps under the Apennines"

La Repubblica Published on Apr 10, 2018

HAWAII VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK - Over 200 earthquakes occurred Wednesday at depths of 4.5 to 5.5 miles below Kīlauea's summit, scientists say.

(BIVN) – A moderate swarm of over 200 earthquakes occurred Wednesday below the summit of Kīlauea volcano.

The seismicity returned to its background rate at about 2:30 a.m. Thursday morning, scientists with the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory report.

The earthquakes were recorded at depths of 4.5 to 5.5 miles below Kīlauea’s summit, where an active lava lake is present within Halemaʻumaʻu Crater. The largest event in the sequence was a Magnitude 2.4, scientists say.

There was no change detected in deformation data due to the earthquake activity, USGS says. This morning, summit tiltmeters were recording small amounts of deflationary tilt, consistent with the deflationary phase of a summit DI event. The summit lava lake remains at a high level, and this morning was measured to be about 105 feet below the rim of the Overlook crater, slightly deeper than it was yesterday. Spattering was periodically visible from the Jaggar Museum yesterday.

Terremoto di magnitudo 4.6 nel Maceratese. Danni, scuole chiuse e 20 sfollati a Pieve Torina

4.6 magnitude earthquake in the Maceratese area. Damages, closed schools and 20 displaced persons in Pieve Torina

10 aprile 2018 Snip: Pic's

The earthquake at 5.11 with epicenter 2 km from Muccia. No injuries, but so much fear.

The belfry of the Church of the '600 Santa Maria di Varano is damaged. Warned in the provinces of Macerata, Ancona, Pesaro, Umbria, part of Tuscany, Lazio, the Aquila area and Rome. Stramondo (Invg): "The earth trembles in the region because of the Adriatic plaque that creeps under the Apennines"

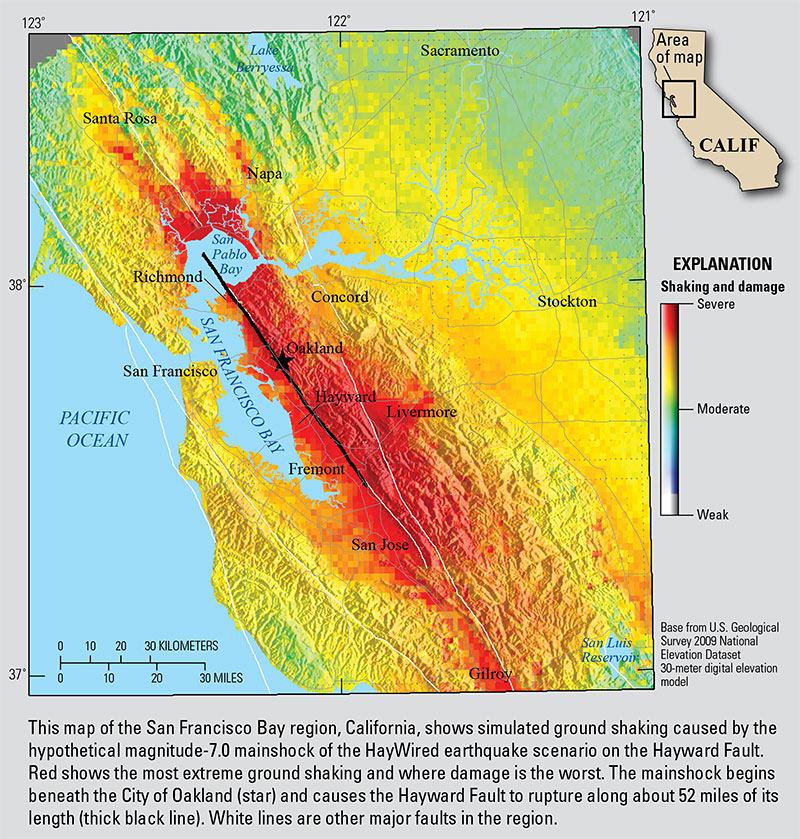

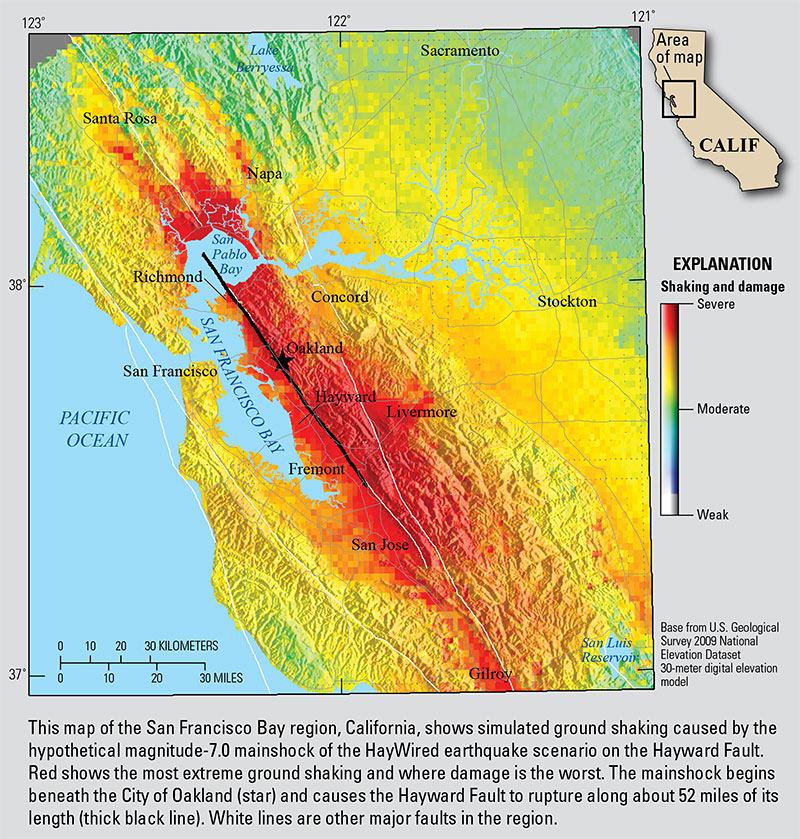

Hayward Fault Is More Dangerous Than We Knew

Published on Apr 18, 2018

A new report from the U.S. Geological Survey says a major earthquake on the Oakland section of the Hayward fault could kill hundreds of people and injure thousands

The USGS report out today examined what could happen in the likely scenario of a 7.0 quake. Similar large earthquakes have occurred on the Hayward fault every 100-220 years for nearly two millennia, and last happened 150 years ago.

The scenario imagines an earthquake centered in Oakland, happening at 4:18 p.m. on the same day as the 1906 San Francisco earthquake: today, April 18.

The quake ruptures the fault for 52 miles, from Fremont to the middle of San Pablo Bay. It causes violent shaking from Richmond to Fremont, killing 800 people from building and structural collapse and damage, and injuring 18,000 people.

In the scenario, roughly 2,500 people need to be rescued from collapsed buildings, and 22,000 people are trapped in elevators.

Scientists also ran the scenario imagining people using the ShakeAlert emergency early warning system and found that if people actually "Drop, Cover, and Hold On" as many as 1,500 non-fatal injuries can be prevented.

The violent shaking causes soils along the San Francisco Bay to become slippery, moving like liquid, and causes landslides in the hills and mountains surrounding the bay, especially the East Bay hills.

East Bay residents could lose water supplies for 6 weeks, and this disruption would also hamper firefighters, who could face some 400 fires from ruptured gas and electricity pipes all over the Bay Area. Thousands of people could be left homeless from the fires.

The report recommends three top priorities to reduce the fatalities and damages from this kind of disaster: replace old and brittle water pipes, enhance building codes, and adopt and use the ShakeAlert early warning system.

"People are willing to pay more for better building codes," Andrew Michael, geophysicist with the U.S.G.S. Earthquake Science Center in Menlo Park, said to KQED's Forum. "I think the important thing is for people to become informed and become engaged in the process to help inform policy."

A USGS map illustrating potential damage from a strong quake on the Hayward fault. (U.S. Geological Survey)

(U.S. Geological Survey)

[SIZE=4][B]https://www.kqed.org/science/1922795/hayward-fault-is-more-dangerous-than-we-knew[/B][/SIZE]Published on Apr 18, 2018

A new report from the U.S. Geological Survey says a major earthquake on the Oakland section of the Hayward fault could kill hundreds of people and injure thousands

The USGS report out today examined what could happen in the likely scenario of a 7.0 quake. Similar large earthquakes have occurred on the Hayward fault every 100-220 years for nearly two millennia, and last happened 150 years ago.

The scenario imagines an earthquake centered in Oakland, happening at 4:18 p.m. on the same day as the 1906 San Francisco earthquake: today, April 18.

The quake ruptures the fault for 52 miles, from Fremont to the middle of San Pablo Bay. It causes violent shaking from Richmond to Fremont, killing 800 people from building and structural collapse and damage, and injuring 18,000 people.

In the scenario, roughly 2,500 people need to be rescued from collapsed buildings, and 22,000 people are trapped in elevators.

Scientists also ran the scenario imagining people using the ShakeAlert emergency early warning system and found that if people actually "Drop, Cover, and Hold On" as many as 1,500 non-fatal injuries can be prevented.

The violent shaking causes soils along the San Francisco Bay to become slippery, moving like liquid, and causes landslides in the hills and mountains surrounding the bay, especially the East Bay hills.

East Bay residents could lose water supplies for 6 weeks, and this disruption would also hamper firefighters, who could face some 400 fires from ruptured gas and electricity pipes all over the Bay Area. Thousands of people could be left homeless from the fires.

The report recommends three top priorities to reduce the fatalities and damages from this kind of disaster: replace old and brittle water pipes, enhance building codes, and adopt and use the ShakeAlert early warning system.

"People are willing to pay more for better building codes," Andrew Michael, geophysicist with the U.S.G.S. Earthquake Science Center in Menlo Park, said to KQED's Forum. "I think the important thing is for people to become informed and become engaged in the process to help inform policy."

A USGS map illustrating potential damage from a strong quake on the Hayward fault.

(U.S. Geological Survey)

(U.S. Geological Survey)angelburst29

The Living Force

April, 19, 2018 - Magnitude 5.9 Quake Strikes Southern Iran

Magnitude 5.9 Quake Strikes Southern Iran - Tasnim News Agency

A magnitude 5.9 earthquake struck Kaki District, in Dashti County, in the southern Iranian Province of Bushehr on Thursday.

According to the Seismological Center of the Institute of Geophysics of Tehran University, it struck at 0634 GMT some 100 kilometers, about 60 miles, east of Bushehr, the provincial capital. The epicenter of the earthquake was about 18 km deep, the center added.

The quake was also felt in Bahrain and other areas around the Persian Gulf. There was no immediate report of damage or injuries.

April, 22, 2018 - Magnitude 4.7 Quake Hits southern Iran

Magnitude 4.7 Quake Hits southern Iran - Tasnim News Agency

An earthquake measuring 4.7 on the Richter scale jolted a district in Iran’s southern province of Fars on Sunday but there were no immediate reports of casualties or damage.

According to Tasnim dispatches, the earthquake occurred in an area near the city of Khonj in Fars Province at 5:42 a.m. local time.

The epicenter, with a depth of 12km, was determined to be at 27.81 degrees latitude and 53.49 degrees longitude.

There were no immediate reports of casualties and the extent of the damages inflicted on the quake-hit area.

Magnitude 5.9 Quake Strikes Southern Iran - Tasnim News Agency

A magnitude 5.9 earthquake struck Kaki District, in Dashti County, in the southern Iranian Province of Bushehr on Thursday.

According to the Seismological Center of the Institute of Geophysics of Tehran University, it struck at 0634 GMT some 100 kilometers, about 60 miles, east of Bushehr, the provincial capital. The epicenter of the earthquake was about 18 km deep, the center added.

The quake was also felt in Bahrain and other areas around the Persian Gulf. There was no immediate report of damage or injuries.

April, 22, 2018 - Magnitude 4.7 Quake Hits southern Iran

Magnitude 4.7 Quake Hits southern Iran - Tasnim News Agency

An earthquake measuring 4.7 on the Richter scale jolted a district in Iran’s southern province of Fars on Sunday but there were no immediate reports of casualties or damage.

According to Tasnim dispatches, the earthquake occurred in an area near the city of Khonj in Fars Province at 5:42 a.m. local time.

The epicenter, with a depth of 12km, was determined to be at 27.81 degrees latitude and 53.49 degrees longitude.

There were no immediate reports of casualties and the extent of the damages inflicted on the quake-hit area.

April 23, 2018 from USGS

M 5.6 - 41km SW of Jiquilillo, Nicaragua

Time2018-04-24 02:29:53 (UTC)

Location12.522°N 87.754°W

Depth 47.0 km

M 5.6 - 41km SW of Jiquilillo, Nicaragua

Time2018-04-24 02:29:53 (UTC)

Location12.522°N 87.754°W

Depth 47.0 km

Trending content

-

-

-

Thread 'Coronavirus Pandemic: Apocalypse Now! Or exaggerated scare story?'

- wanderingthomas

Replies: 30K -