...and especially with the up to 9 m uplift of a more than 100 km long segment of Crete.

The magnitude of the uplift would indicate one of the largest earthquakes

ever recorded on the earth (magnitude over 8).[...]

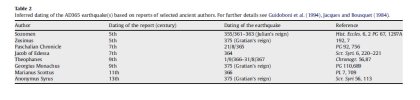

Historical data concerning earthquakes and tsunami destruction

circa AD365 are fragmentary, ambiguous and imprecise. However,

a destructive tsunami which affected the coasts of Egypt and

widespread seismic destructions in Crete, Sicily and Libya seem

documented beyond any reasonable doubt (for a summary, see

Guidoboni et al., 1994; Stiros, 2001; Stiros and Papageorgiou, 2001;

Kelly, 2004).[...]

The famous text by Ammianus Marcelinnus (26.10.15–19)

reports that on July 21st, AD365, a tsunami-associated earthquake

affected Alexandria in Egypt, and later authors report that this

event became a legend for more than a millennium commemorated

in this city for more than 200 years as the ‘‘Day of Horror’’ (for

a summary, see Guidoboni et al., 1994; Stiros, 2001). On the

contrary, in the Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu in Egypt, it is

clearly stated that at least a large part of the ancient city was not

affected by the tsunami (LXXXII, 19–21, English 1916 translation

from a 7th c. version).[...]

Further contribution to the study of the AD365 tsunami provide

models of propagation of tsunami generated south of Crete (Tinti

et al., 2005; Yolsal et al., 2007; Shawet al., 2008; Lorito et al., 2008).

These models cannot support the hypothesis of tsunami from this

area seriously affecting Alexandria in Egypt, especially the polarity

of the tsunami (retreat of waters prior to the tsunami flooding,

explicitly described by Ammianus Marcelinus). In particular, Lorito

et al. (2008) indicate that tsunami generated in SW part of the

Hellenic arc can only have a minor impact (waves of sub-meter

amplitude) along the Croatian coasts in the Adriatic Sea.[...]

In one of these graphs new land formed after the AD365 event is

marked, while the diagram of Flemming (1978) for the whole of

Crete shows the contrast between uplift in the western and

subsidence in the eastern part of the island. As shown in Fig. 2a, the

AD365 uplift extends as far as the Antikythira Islet. No evidence of

uplift or of subsidence was found in Kythira or Gavdos Ilset (Fig. 2a;

P. Pirazzoli, personal communication). After this uplift, relative sealevel

remained essentially stable on an island-wide scale, raising

questions as to whether the earthquake cycle in Crete is a ‘‘typical’’

one (Stiros, 1996a).[...]

Evidence of a major earthquake

There are several lines of evidence that the uplift dated by

radiocarbon at circa 1550BP was associated with a major earthquake

in AD365:

Biological evidence: very fragile Bryozoans of the infralittoral

zone are preserved exposed above the water. This is evidence that

Bryozoans rapidly crossed the midlittoral zone, where erosion is

intense, without been eroded (Thommeret et al., 1981; Pirazzoli

et al., 1989). Hence there is biological evidence of a rapid,

conspicuously seismic uplift of Crete, and not of slow, non-seismic

uplift during a relatively long period (e.g. tens or hundreds of

years).[...]

Archaeological evidence: Stiros (2001), Stiros and Papageorgiou

(2001) and Stiros et al. (2004) presented or summarized widespread

evidence of destruction layers that are related to earthquake(

s) in circa AD365 in at least three towns of Crete along

a distance of the order of 150 km (see Fig. 4). Evidence of an

earthquake was clear, for instance people killed and buried by

fallen roofs of houses, in some cases with glasses at hand and with

coins in their pockets (compare with Stiros, 1996b). Numismatic

and other evidence indicates that all these destructions are likely to

have occurred in AD365 (Table 3).[...]

Recent evidence summarized elsewhere provides additional

evidence for a major seismic destruction shortly after AD364 in

various parts of Crete, including at Knossos, near Herakleion in

central Crete, where a ‘thesaurus’’ (treasure, hoard) of about 1000

coins was found hidden in the remains of the walls of an ancient

house. In the absence of banks, such ‘‘thesauroi’’ reflect a tradition

in antiquity to safely hide money. The distribution of the date of

production of the coins of this ‘‘thesaurus’’ clearly indicates that it

was deposited between AD364–AD367 (Fig. 5), and it was then

abandoned (presumably) because its owner disappeared (Sidiropoulos,

2004)...However, several forgotten hoards of

this period were found in Crete, and this provides evidence suggesting

a wider extinction of their owners during an event of

unprecedented scale in the history and archaeology of the region. If

on the basis of the available data, epidemics and war can be

excluded, extensive seismic destruction remains the likely reason.

In addition, since coins of a slightly later age have been found in

Crete, demonstrating a continuity of coin circulation in this island

(Fig. 5), the most recent coins in the hoards provide a reliable and

precise estimate of the date of their deposition (Stiros, unpublished

data).

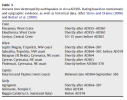

Except for Crete, systematic archaeological excavations in

Cyprus, Libya and Southern Italy have revealed clear signs of

extensive seismic destruction which in many cases fall within

a period some months to a few years, correlating with literary

evidence for a regionally destructive event (or sequence of events)

circa AD365 (Fig. 1; Table 3). The most spectacular and clear are

earthquake victims, people, occasionally whole families, and horses

at Kourion, near Paphos, Cyprus (see Sorren and Davis, 1985;

Sorren, 1988). In many cases the dating of these events, based on

inscriptions and on numismatic evidence, is accurate to within

months or years. These data are summarized in Table 3 and permit

identification of at least large parts of the regions which were hit by

earthquakes circa AD365.[...]

Evidence summarized above indicates that the up to 9 m uplift

and tilting of Crete was an episodic event which correlates with

large-scale seismic destruction of the island in AD365. Elastic

dislocation analysis of this uplift indicates that it can be associated

with a thrust offshore of southwestern Crete, which produced an

earthquake of a magnitude (M > 8.5), unusual in the geologic

history of the island, at least over a period of 120,000 years (since

the Last Interglacial, Pirazzoli et al., 1982; Pirazzoli, 1986; Kelletat,

1991). This was not an isolated event, but belonged to a seismic

sequence which affected Cyprus, Libya, Sicily and probably other

areas, and it was clustered in a short time period, short enough to

be regarded by the ancients as a single, universal event (‘‘terraemotu

per totum orbem facto’’, Migne, PL 27, 694). Such a seismic

sequence is clearly consistent with current understanding of other

giant earthquakes, for instance the 1960 Chile earthquake (Plafker

and Savage, 1970).

If the AD365 earthquake had produced a tsunami by faulting of

the seabed, the propagation of this tsunami would be very similar

to that modelled by Tinti et al. (2005), Yolsal et al. (2007), Shaw

et al. (2008) and Lorito et al. (2008). It is, however, questionable

whether modelled tsunami can account for the reported destruction

in the Nile Delta (see above).

Another characteristic of the AD365 earthquake is that, in spite

of its magnitude, the scale of the destruction produced and its

association with a series of other major destructive earthquakes

(Pirazzoli, 1986; Pirazzoli et al., 1996), it does not represent a catastrophic

event leading to the collapse of the Roman Empire which

was indeed in a deep crisis. The AD365 earthquake, indeed, seems

to represent only a rather minor cultural discontinuity in Crete,

marking the transition from the Roman to the Christian era in the

island, as stratigraphic data summarized in Stiros (2001) and Stiros

and Papageorgiou (2001) reveal. It is interesting that Gortyn, capital

of Crete in antiquity, was destroyed by the AD365 and other

smaller, subsequent earthquakes, but every time it rapidly recovered,

until it was finally destroyed by a lesser earthquake in the 7th

c. AD, because the political background at this period did not

support its post-seismic recovery (DiVita, 1996).