A Secret Database of Child Abuse

A former Jehovah's Witness is using stolen documents to expose allegations that the religion has kept hidden for decades.

[As many as 23,720 pedophiles are named in the database.]

Douglas Quenqua Mar 22, 2019

A former Jehovah's Witness is using stolen documents to expose allegations that the religion has kept hidden for decades.

www.theatlantic.com

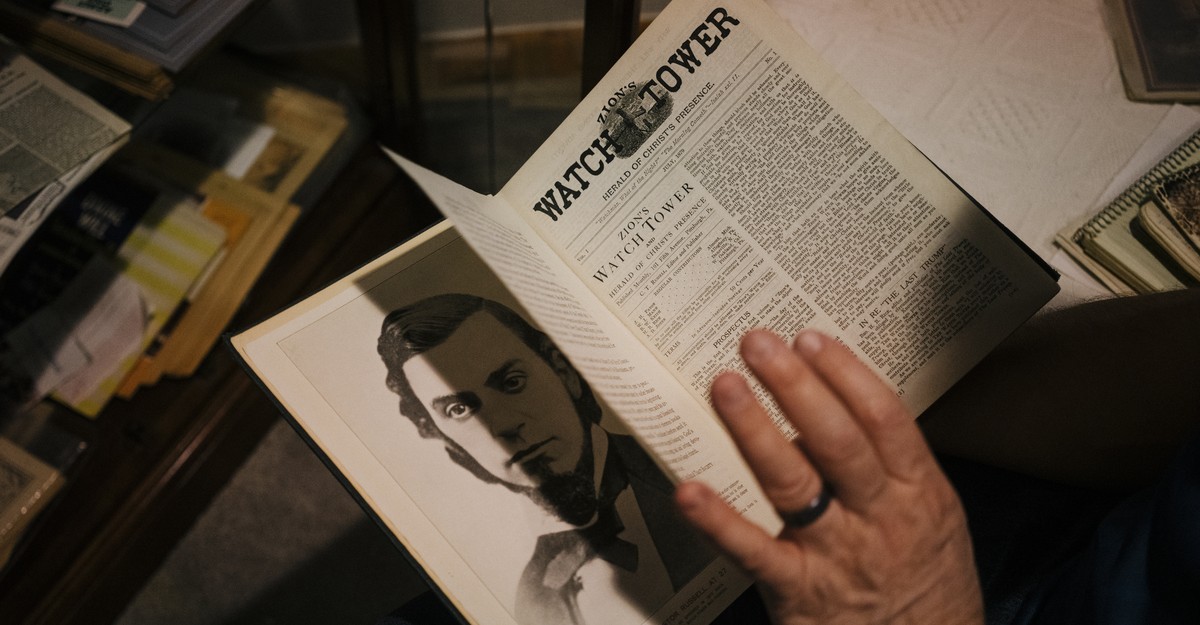

In March 1997, the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, the nonprofit organization that oversees the Jehovah’s Witnesses, sent a letter to each of its 10,883 U.S. congregations, and to many more congregations worldwide. The organization was concerned about the legal risk posed by possible child molesters within its ranks. The letter laid out instructions on how to deal with a known predator: Write a detailed report answering 12 questions—Was this a onetime occurrence, or did the accused have a history of child molestation? How is the accused viewed within the community? Does anyone else know about the abuse?—and mail it to Watchtower’s headquarters in a special blue envelope. Keep a copy of the report in your congregation’s confidential file, the instructions continued, and do not share it with anyone.

Thus did the Jehovah’s Witnesses build what might be the world’s largest database of undocumented child molesters: at least two decades’ worth of names and addresses—likely numbering in the tens of thousands—and detailed acts of alleged abuse, most of which have never been shared with law enforcement, all scanned and searchable in a Microsoft SharePoint file. In recent decades, much of the world’s attention to allegations of abuse has focused on the Catholic Church and other religious groups. Less notice has been paid to the abuse among the Jehovah’s Witnesses, a Christian sect with more than 8.5 million members. Yet all this time, rather than comply with multiple court orders to release the information contained in its database, Watchtower has paid millions of dollars to keep it secret, even from the survivors whose stories are contained within.

That effort has been remarkably successful—until recently.

A white Priority Mail box filled with manila envelopes sits on the floor of Mark O’Donnell’s wood-paneled home office, on the outskirts of Baltimore, Maryland. Mark, 51, is the owner of an exercise-equipment repair business and a longtime Jehovah’s Witness who quietly left the religion in late 2013. Soon after, he became known to ex–Jehovah’s Witnesses as John Redwood, an activist and a blogger who reports on the various controversies, including cases of child abuse, surrounding Watchtower. (Recently, he has begun using his own name.)

When I first met Mark, in May of last year, he appeared at the front door of his modest home in the same outfit he nearly always wears: khaki cargo shorts, a short-sleeved shirt, white sneakers, and sweat socks pulled up over his calves. He invited me into his densely furnished office, where a fan barely dispelled the wafting smell of cat food. He pulled an envelope from the Priority Mail box and passed me its contents, a mixture of typed and handwritten letters discussing various sins allegedly committed by members of a Jehovah’s Witness congregation in Massachusetts. All the letters in the box had been stolen by an anonymous source inside the religion and shared with Mark. The sins described in the letters ranged from the mundane—smoking pot, marital infidelity, drunkenness—to the horrifying. Slowly, over the past couple of years, Mark has been leaking the most damning contents of the box, much of which is still secret.

Mark’s eyebrows are permanently arched, and when he makes an important point, he peers out above his rimless glasses, eyes widened, which lends him a conspiratorial air.

“Start with these,” he said.

Among the papers Mark showed me that day was a series of letters about a man from Springfield, Massachusetts, who had been disfellowshipped—a form of excommunication—three times. When the man was once again reinstated, in 2008, someone working in a division of Watchtower wrote to his congregation, noting that in 1989 he was said to have “allowed his 11-year-old stepdaughter to touch his penis … on at least two occasions.”

I was struck by the oddness of the language. It insinuated that the man had agreed to, rather than initiated, the sexual contact with his stepdaughter.

After I left Mark’s house, I tracked down the stepdaughter, now 40. In fact, she told me, she had been only 8 when her stepfather had molested her. “He was the adult and I was the kid, so I thought I didn’t have any choice,” she said. She was terrified, she told me. “It took me two years to go to my mom about it.”

Her mother immediately went to the congregation’s elders, who later called the girl and her stepfather in to pray with them. She remembers it as a humiliating experience.

Her stepfather was eventually disfellowshipped for instances that involved “fornication,” “drunkenness,” and “lying,” according to the letters. But according to the stepdaughter, his alleged molestation of her resulted only in his being “privately reproved,” a closed-door reprimand that is usually accompanied by a temporary loss of privileges, such as not being allowed to offer comments during Bible study or lead a prayer. The letters make no reference to police being notified; the stepdaughter said her mother was encouraged to keep the matter private, and no attempt was made to keep the stepfather away from other children. (Calls to the congregation’s Kingdom Hall—the Witness version of a church—for comment went unanswered.)

By the time the letters were written, the man was attending a different congregation and had married another woman with children; he is still part of that family today. Near the end of the final letter in Mark’s possession is a question: “Is there any responsibility on the part of either body of elders … to inform his current wife of his past history of child molestation?”

Mark O’Donnell’s childhood was an isolated one. His parents, Jerry and Susan, had started attending Jehovah’s Witness meetings in the mid-1960s. Another couple from Baltimore had told them of Watchtower’s prediction that the world would end in 1975, bringing death to all non-Witnesses and transforming Earth into a paradise for the faithful. In 1968, just after Mark was born, Jerry and Susan were group-baptized in a swimming pool in Washington, D.C. Mark was an only child, and he inherited his father’s peculiar love of record-keeping. Mark would show up to meetings at the Kingdom Hall with a briefcase full of religious texts.

As in any religion, there’s some variation among Jehovah’s Witnesses in how strictly they interpret the teachings that govern their faith; Mark’s upbringing seems to have been especially stringent. As a child, he attended at least five meetings a week, plus several hours of private Bible study. On Saturday mornings, he joined his parents in “field service,” knocking on doors in search of converts. He was taught that most people outside the organization were corrupted by Satan and, given the chance, would try to steal from him, drug him, or rape him. Mainstream books and magazines were considered the work of Satan. If he broke any of the religion’s main rules, he could be disfellowshipped, meaning even his own family would have to shun him.

Throughout Mark’s childhood, he heard elders cite Proverbs 13:24: “Whoever holds back his rod hates his son.” Mark’s parents took the lesson to heart and beat him frequently. The religion forbids celebrating birthdays, voting, serving in the military, and accepting blood transfusions, even in life-and-death situations. Witnesses were encouraged to devote themselves to bringing more converts into the religion before the end of the world arrived. “Reports are heard of brothers selling their homes and property” to spend their last days proselytizing, said a Watchtower publication in 1974. “Certainly this is a fine way to spend the short time remaining before the wicked world’s end.” Some Witnesses stopped going to the doctor, quit their jobs, or ran up debt.

But piety, Mark noticed, did not always translate to morality. When he was 12, Mark became suspicious of a local Witness named Louis Ongsingco, a flight attendant who would bring home Toblerone bars for the local Witness kids and invite them to his apartment to act out religious plays. Mark noticed Ongsingco touching young girls in a way that made him uncomfortable. He told an elder about his concerns. But rather than take action against Ongsingco, the elder told him what Mark had said. Days later, Ongsingco pulled Mark aside and scolded him.

Mark’s instincts seem to have been right. In 2001, one of Mark’s childhood friends, Erin Michelle Shifflett, along with four other women, sued Ongsingco for sexual assault. The cases were settled out of court for an undisclosed sum. Ongsingco died in 2016.

To Mark, the lesson was that for all the emphasis the elders placed on moral purity, there was no greater sin than speaking out against other Witnesses.

By the time Mark was in high school, in the early 1980s, 1975 had come and gone, but Watchtower had a new prediction for the apocalypse. It said that the world would end before the passing of the generation that was alive in 1914. At the time, the youngest members of that generation were 70, so the new prediction created a sense of urgency.

“My parents basically told me, ‘You’re not even going to live to graduate from college,’” Mark said. At 17, despite having a year of college credit and a guidance counselor imploring him to apply, he decided to settle for a high-school diploma. He was baptized and later started his exercise-equipment repair company. The business provided enough flexibility for him to perform 50 hours of field service for the Witnesses a month, which qualified him for the rank of auxiliary pioneer.

Though many Witnesses left the religion after 1975, membership was on the upswing by the 1990s, and the organization was building new Kingdom Halls. Mark was installing a sound system in a new hall in Baltimore in the fall of 1997 when a young woman named Kimmy Weber asked to borrow his ladder.

At 20, Kimmy was putting in more than 90 hours of field service a month, making her a full-fledged pioneer. She had completed a two-year program at a community college on a scholarship, and would later get permission from the local elders to get her bachelor’s degree. Mark was drawn to her drive and intensity. He tracked down her email address; they flirted over AOL Instant Messenger and were married within eight months. They wanted to start a family, but decided to wait until after the arrival of paradise on Earth, when they, and their children, would be perfect. In the meantime, Kimmy began opening their home to abused and abandoned cats.

As Mark’s business grew, he brought on employees, mostly other Witnesses. When he and Kimmy had saved enough money to buy the house across the street as a rental property, they filled its three units with other Witnesses. There were ski vacations, softball games, dinner parties, and game nights—always with friends who shared their faith.

But as much as Mark enjoyed his friends’ company, he started to chafe at the insularity of their social life. It felt less like intimacy and more like a self-imposed bubble. These frustrations eventually grew into suspicions about Watchtower itself. He’d heard rumors that the organization was covering up cases of pedophilia and child abuse. But Watchtower always dismissed such criticism as “apostate-driven lies.”

A few years after he and Kimmy married, he saw a protester outside a Witness convention holding a sign that read a jw elder molested me. “I looked at that sign,” Mark told me, “and I locked it in my brain. I’ll never forget it. I said to myself, There’s no way he’s lying. Nobody would stand out there and hold a sign that says an elder molested me unless it really happened. No way. He’s telling the truth.”

Watchtower adjusted its estimates for the apocalypse several more times. In 2010, it introduced the Overlapping Generations theory, which claims that the end will come before the death of everyone who was alive at the same time as anyone who was alive in 1914. Mark found these revised predictions difficult to accept.

In late 2013, Mark had an extreme reaction to an antibiotic and was confined to his couch for several weeks, away from the meetings and Bible studies. Left alone with his thoughts, he began to admit to himself that he no longer believed Armageddon was imminent. The Jehovah’s Witnesses he knew were no more deserving of God’s mercy than the nonbelievers he’d met. And here he was, 45 years old and facing a health crisis. How much more of his life was he willing to waste inside the bubble?

That November, as he and Kimmy were preparing to spend the weekend at a friend’s house, Mark suddenly stopped packing and told Kimmy he couldn’t maintain the facade anymore. He never attended another meeting.

Though Kimmy kept going to meetings, her Witness friends pressured her to leave her marriage. “They would just come out of the blue with unsolicited advice,” she told me. “‘Don’t forget, Kimmy, Jehovah comes first!’ ‘At some point, you’ll have to make your choice!’” But she didn’t want to leave Mark. “I just tried to figure out, how can I stay a Witness and him not?”

Mark’s doctor had suggested that he take daily walks as part of his recovery. Kimmy already had a routine of evening strolls, and he began to join her. Mark told Kimmy that he’d once planned to be an engineer, and that he felt he’d been forced to choose between God and his ambition. Kimmy said she’d once dreamed of becoming a doctor or a veterinarian. She revealed that she’d always been terrified that having kissed Mark before they were married meant she might die at Armageddon. She told Mark she feared that, at 36, she’d missed her chance to have children.

Their walks got longer, eventually reaching eight or 10 miles a night. “She was trying to get into my head, to figure out what was going on,” Mark told me. By this point, he’d given himself permission to delve into so-called apostate material, books such as Crisis of Conscience, a 1983 exposé written by a former member of the Jehovah’s Witnesses Governing Body. He also started watching YouTube videos by Lloyd Evans, a former British elder who has amassed a dedicated following with his anti-Watchtower arguments. A Witness can be disfellowshipped for sharing such material, so Mark didn’t tell Kimmy.

Instead, he shared small pieces of information to challenge what Kimmy had been taught, such as the truth about the 1975 doomsday prediction. Kimmy had grown up believing that overzealous Witnesses, not Watchtower, had chosen that date. But Mark, who rarely threw away anything, encouraged her to read the Watchtower articles exhorting members of the faith to sell their homes. Kimmy began to entertain the kind of doubts she’d been trained to ignore. “But I think the big trigger for her,” Mark said, “was when I mentioned Candace Conti.”

Candace Conti, now 33, was raised as a Jehovah’s Witness in Fremont, California. When she was 9, the elders in her congregation paired her with a man named Jonathan Kendrick for Saturday-morning field service. Instead of going door-to-door to preach the word of God, Kendrick would take Conti to his house and molest her, she says. She estimates this went on for about two years.

Years later, after Conti had left the Witnesses, she discovered Kendrick’s name on the federal sex-offender registry. When she went back to the elders in her former congregation to tell them about the abuse, she was rebuffed by something called the two-witness rule.

Rooted in Deuteronomy 19:15—“No single witness may convict another for any error or any sin that he may commit”—the two-witness rule states that, barring a confession, no member of the organization can be officially accused of committing a sin without two credible eyewitnesses who are willing to corroborate the accusation. Critics say this rule has helped turn Witness communities into havens for child molesters, who rarely commit crimes in the presence of bystanders.

The elders told Conti that without a second witness to the molestation, there was nothing they could do. (When reached for comment, Watchtower’s Office of Public Information said, “Our policies on child protection comply with the law, including any requirements for elders to report allegations of child abuse to authorities.” Watchtower declined to comment on specific cases out of respect for the privacy of all involved.)

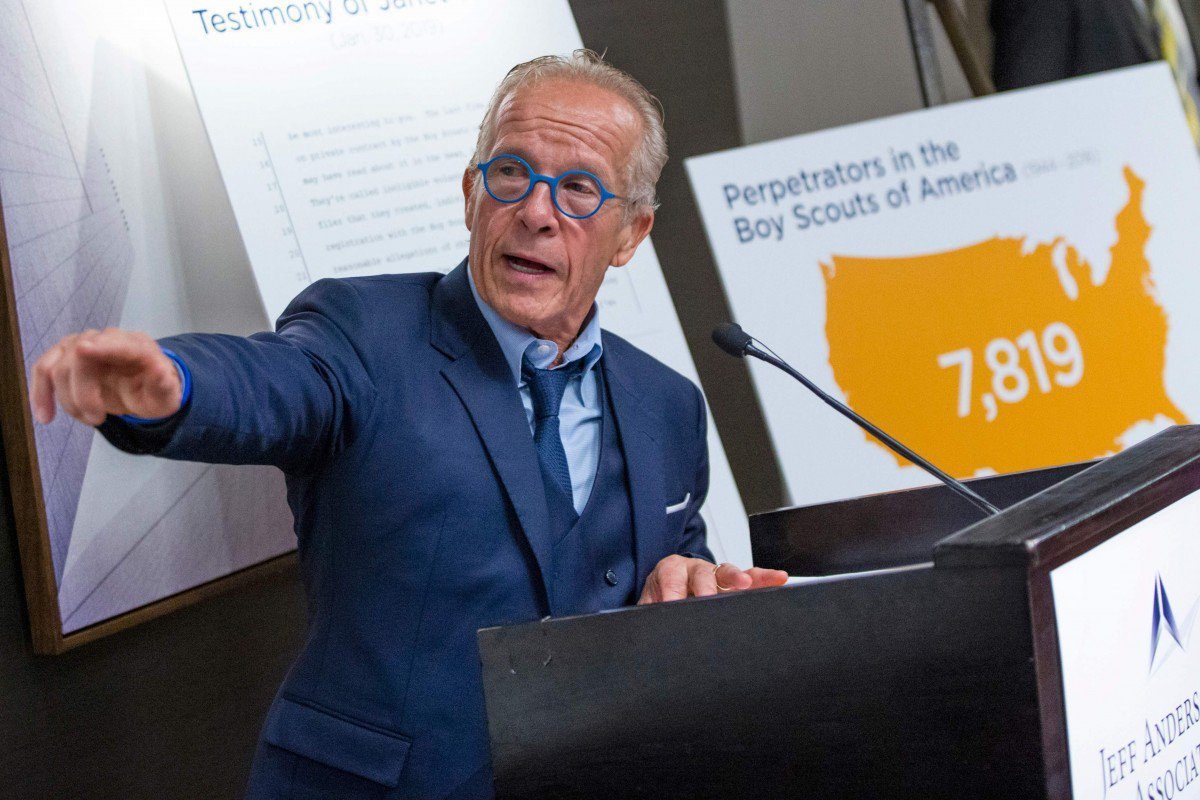

Conti asked the elders to consider a plan she had devised for tracking child molesters within the organization. When they refused, she sued Watchtower, her former congregation, and Kendrick. During depositions, the elders admitted that they’d long known Kendrick had a history of child molestation—they knew before they paired him with Conti for door-to-door ministry, and before they rejected her story about the abuse. In 2012, a jury awarded Conti $28 million, believed to be the largest jury verdict ever for a single victim in a child-abuse case against a religious organization. (On appeal, judges reduced the damages to less than $3 million. Kendrick has always denied Conti’s allegations.)

Others had come forward with accusations against Watchtower before, but Conti refused to take a settlement, and the trial, with its blockbuster monetary award, became a major news story. In the years since, Watchtower has faced dozens of similar lawsuits from victims who say the organization’s policies enabled and protected their abusers. In addition to the 1997 “special blue envelope” letter,these suits have cited a 1989 letter in which Watchtower discouraged elders from reporting wrongdoing to civil authorities. “There is ‘a time to keep quiet,’ when ‘your words should prove to be few’ (Ecclesiastes 3:7; 5:2),” it read. “Improper use of the tongue by an elder can result in serious legal problems for the individual, the congregation, and even the Society.”

It was one such lawsuit that brought attention to the database.

José Lopez was 7 years old when he was molested by Gonzalo Campos, a fellow Witness whom the local elders had recommended as a mentor, despite knowing that Campos allegedly had a history of molesting young boys. When Campos assaulted Lopez in a La Jolla, California, home in 1986, the boy told his mother, who immediately reported Campos to the elders. They said they would handle the situation, and told her not to call the police. Yet Campos continued to rise in the organization, eventually becoming an elder. In 2010, he fled to Mexico, where he later confessed in a deposition to molesting Lopez and several other young boys.

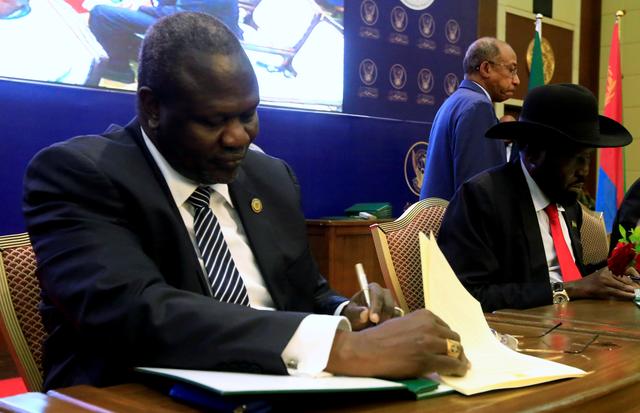

Lopez filed a lawsuit against Watchtower in 2012. When his lawyer, Irwin Zalkin, requested that Watchtower turn over all documents related to Campos and other known molesters, the organization at first refused, saying it lacked the resources to locate and sort all the information. But a senior official for Watchtower later testified that all the information had, in fact, been scanned and stored in a Microsoft SharePoint database.

Zalkin introduced a software expert who testified that Watchtower should be able to produce the documents in as little as two days using simple search terms. Still, Watchtower did not comply. The judge grew frustrated and eventually barred the organization from mounting a defense, and handed Lopez a $13.5 million award. (An appellate court overturned the ruling, saying the judge should have sanctioned Watchtower incrementally; the case was settled for an undisclosed sum in January 2018.)

When Zalkin raised the issue of the database in another case against Campos, in 2016, the judge ordered Watchtower to pay a fine of $4,000 a day until it handed over the documents. Watchtower racked up $2 million in charges (which it later paid) before settling the case in February 2018. Zalkin has once again requested the release of the database documents in another California case he’s brought on behalf of a former Witness.

Exactly how many alleged pedophiles are named in the database has been the source of wide-ranging speculation. In 2002, one former elder said the number was 23,720. (Watchtower would not comment on the number at the time except to say that it was considerably lower.) During the Lopez trial, a Watchtower attorney estimated that the organization had received 775 blue envelopes from 1997 to 2001, but did not say how many it had received since then. Perhaps most tellingly, in 2015, an Australian investigation found that the perpetrators listed in the database represented 1.5 percent of that country’s Witness population of 68,000. Assuming the percentage is comparable in the U.S., which has a Witness population of 1.2 million, the number of alleged American abusers in the database would be 18,000.

U.S. authorities have so far taken no action against Watchtower, but other countries have launched investigations. In 2016, a royal commission in Australia found that Watchtower demonstrated a “serious failure” to protect children, including not reporting more than 1,000 alleged perpetrators of sexual abuse (more than half of whom have confessed to committing the abuse) and at least 1,800 victims in that country since 1950. In 2014, the U.K.’s Charity Commission opened two investigations, one of which is ongoing. Last year, in the Netherlands, then–Justice Minister Sander Dekker urged Watchtower to conduct an independent investigation into hundreds of abuse allegations received via a special hotline. Watchtower declined.

By the time Mark told Kimmy about the Conti trial, in August 2014, she was starting to see things differently, too—enough that she decided to read the trial transcript. “It was like someone just punched me in the stomach,” she told me. “It was like this whole crack happened in my head.”

Mark knew that Kimmy had suffered physical and psychological abuse at the hands of her mother, who was mentally ill, but Kimmy didn’t talk about it much. Now she began to open up. She told Mark about how her mother would lock her and her two siblings in their bedrooms or the basement for days with no food and only a litter box for a toilet. How she would keep them up all night by banging on pots and pans, then send them to school delirious and malnourished. She was also physically abusive toward Kimmy’s father, who worked long hours and was largely unaware of how his wife was treating their children. “She would beat us every which way you can imagine. Scream at us, cuss at us for hours and hours and hours,” Kimmy said. There was sexual abuse, too, which Mark hadn’t known about. (My attempts to contact Kimmy’s mother for comment were not successful.)

Like many abusers, Kimmy’s mother used animal cruelty to keep her kids from telling anyone. She would drown kittens in the toilet, then hang the corpses from a ceiling fan in their bedrooms or place them in a jar by their bed, “making the point that she could kill us if we didn’t cooperate or we told,” Kimmy said. “That’s why I’m always trying to rescue cats,” she added, laughing darkly. “That’s some easy psychology there.”

But Kimmy did tell. As a 12-year-old, she went to the elders in her congregation for help. They told her she couldn’t report her mother to the police, “because it would make the organization look bad,” she recalled. They discouraged her from seeking counseling, because a therapist might blame the religion or get the authorities involved. Finally, the elders asked Kimmy a question: If her mother did end up killing her, could that prevent Jehovah from resurrecting her at Armageddon? “Of course, I said no,” Kimmy said, rolling her eyes. “They told me, ‘Go home and obey your mother.’”

She told again at 15, after she’d been baptized. This time, the elders said they would need a second eyewitness before they could intervene. Kimmy offered her brother—who has corroborated Kimmy’s allegations for this story—but was told that his testimony wouldn’t be credible, because he wasn’t baptized. “It was my word against my mother’s word,” Kimmy said. Years later, she would learn that her brother had already reported the abuse to the same elders.

Kimmy had heard of the two-witness rule, but she’d assumed it was a peculiarity of her local congregation. When she read the transcript of the Conti trial, she discovered that it was Watchtower doctrine and had been used for decades to prevent other abused children from getting help. “The scales fell off my eyes,” she said. Soon, both she and Mark would leave the organization for good.

Over the next couple of years, the implications of Kimmy and Mark’s decision became apparent.

One of Mark’s employees quit. Two of the couple’s tenants moved out in the middle of the night. Close friends stared at their feet when Kimmy ran into them at Walmart. “I went and hid three rows down and cried,” she told me. Mark’s relationship with his parents, always strained, disintegrated. His business faltered. He and Kimmy had some savings to fall back on and would find other tenants. But in his mid-40s, with no college degree or résumé, Mark faced an uncertain future.

On a lark, he emailed Lloyd Evans, the British activist with the YouTube videos. Mark told Evans his story and thanked him for the work he was doing. To his surprise, Evans wrote back, suggesting some online ex-Witness groups he should join. Still wary of being labeled an apostate (neither he nor Kimmy had been officially disfellowshipped, though they’d stopped attending meetings), Mark joined Facebook under the pseudonym John Redwood—an homage to Evans, whose pen name was John Cedars—and began finding others with similar stories. As he connected with ex-Witnesses around the world, he was struck by how similar their accounts were to his own. He began writing about his experiences on Facebook. His posts spurred conversations among former Witnesses, giving him a new sense of purpose.

In the summer of 2015, the ex-Witness community was transfixed by Australia’s royal-commission hearings, live-streamed online, into sexual abuse in religious organizations. The commission had been trying to get testimony from a member of Watchtower’s Governing Body—the organization’s all-male ruling council, which then consisted of eight men. By a strange twist of fate, one member, Geoffrey Jackson, was in Australia at the time, tending to his sick father.

Watchtower had managed to avoid a subpoena by claiming that the Governing Body was strictly advisory and played no role in creating policy. Mark—who had obsessively collected Watchtower literature his entire life—had the evidence to prove this wasn’t true. He dug out a copy of the “Branch Organization Manual,” an obscure document explaining all the functions of the Governing Body, and emailed it to Angus Stewart, the lead litigator in the proceedings. Stewart used the manual to subpoena Jackson.

In front of the commission, Jackson became the first active member of Watchtower’s Governing Body to acknowledge that “child abuse is a problem right throughout the community.” He also admitted that in most cases, children who make such charges against Watchtower are telling the truth.

It was an emotional moment for those whose abuse Watchtower had denied. Mark received an email from Stewart saying that the “Branch Organization Manual” had proved to be crucial in securing Jackson’s testimony. Perhaps, Mark thought, his extensive collection of Watchtower ephemera and his encyclopedic knowledge of the religion could be used for something other than recruiting.

Still using his John Redwood pseudonym, Mark became a regular contributor to Evans’s anti-Watchtower news site, JWsurvey.org. Trey Bundy, who has covered Watchtower’s sex-abuse scandals for the Center for Investigative Reporting, invited Mark to speak at a 2017 conference on the topic in London that also featured Zalkin, the attorney, and Michael Rezendes, the Boston Globe reporter who won a Pulitzer Prize with his co-workers for their investigation of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. The conference marked the first time that Mark used his real name as an activist, figuring the Witnesses he knew in Baltimore were unlikely to hear about the small overseas gathering.

Mark also used JWsurvey, where he continued writing under his pseudonym, to encourage Witnesses to expose Watchtower’s abuses—a call that has yielded hundreds of emails. “He just comes off as so sincere and knowledgeable and articulate,” says Faith McGinn, a former Witness and an abuse survivor who reached out to Mark last April. “That’s what prompted me to finally come forward.” Mark has built an international network of abused, disfellowshipped, and aggrieved Witnesses, whom he has connected to journalists, attorneys, and one another. “Mark is probably the key ex-JW in the ex-JW community,” says Jason Wynne, the founder of AvoidJW.org.

A Jehovah’s Witness who has started doubting the religion’s tenets but not yet left the organization is said to be “physically in, mentally out,” or PIMO. In 2017, a PIMO man and his girlfriend began walking into Kingdom Halls in Massachusetts, opening locked file cabinets with a set of stolen keys, and removing or making copies of sealed documents. They had heard chatter about Watchtower covering up child abuse and, at first, simply wanted to see the evidence themselves.

Most of the documents they took were letters between local elders and Watchtower headquarters, or from one congregation to another, discussing the alleged sins of individual congregants. One young man was disfellowshipped for stealing candy bars, another for refusing to remove a sign from his van window that said beating children violates God’s law. A woman was disfellowshipped for having sex with her ex-husband when he came over to plow her driveway during a snowstorm.

But they also gathered dozens of letters dealing with accusations of rape, domestic violence, and molestation, including several questionnaires required by the 1997 “special blue envelope” letter. In total, 12 individuals are named as suspected child molesters, though missing documents make it difficult to piece together some of the stories.

Not knowing what to do with the documents, the PIMO man—who has requested anonymity and prefers the code name Judas—posted a redacted version of a single letter he had stolen on an ex–Jehovah’s Witnesses subreddit. Just five sentences long, the letter informed Watchtower that a ministerial servant had admitted to physically and mentally abusing his wife for years. In the most recent incident, he beat her so badly that she would have sought medical attention, “if it were not for her concern over the reproach it would bring on Jehovah’s name.” As punishment, the husband had been stripped of his rank and had lost all “special privileges,” like handling the microphone at Kingdom Hall meetings. No mention was made of involving police or taking steps to protect the wife. Judas had blacked out the names of the couple and the congregation, but not the date.

“It was just one simple letter that shocked me,” Judas told me. “I wanted to see if this would get anyone’s eyes who is really important and could tell me what I should do with this information.” His plan worked. Jason Wynne saw the letter and sent Judas a private message, warning him that he could be exposing himself and others to legal trouble or harassment by posting sensitive documents online. Judas replied, asking for advice on how to release his other documents.

At Wynne’s request, Mark reached out to Judas with a plan to release the information while still protecting his identity. Judas went to a distant post office and mailed him the documents in a USPS Priority Mail box with no return address. He also used secure channels to send scanned copies to Mark and Wynne. Though they wanted to eventually leak redacted versions of every document involving a criminal act, they decided to start with one big story: the case of a Witness man from the Palmer Congregation in Brimfield, Massachusetts, who allegedly abused his two daughters and another young girl.

The story plays out across 33 letters—69 pages in all—between the congregation and Watchtower headquarters. One of the man’s daughters said he had tied her down and molested her; the other said he had raped her repeatedly for nine years. He allegedly took one of his daughters into the woods and showed her where he would bury each of her body parts if she told. The girl who wasn’t his daughter said he raped her in his neighbor’s mobile home when she was 4.

At first, the elders took only nominal action because one of the sisters refused to accuse her father in person. In 2003, the elders finally disfellowshipped the man after he confessed to molesting one daughter. But he was reinstated a year later, partly because the daughter who had accused him of years of rape refused to answer new questions from the elders, who had pressured her and her sister not to alert civil authorities.

Mark and Wynne, nervous about trafficking in stolen documents, wanted to create another layer of protection for Judas and themselves. So Wynne approached Ryan McKnight, the proprietor of MormonLeaks.io, a site dedicated to transparency in the Mormon Church. They shared the Palmer documents with McKnight, who used them as the inaugural posts for a new site, FaithLeaks.org, and worked with a reporter from Gizmodo to independently confirm the story. Mark and Wynne never shared any details about Judas’s identity with McKnight, so that he could honestly say he didn’t know who had stolen the letters.

On January 9, 2018, the documents went live on FaithLeaks, and Gizmodopublished its story. Other American outlets picked it up—as did media in the U.K., Finland, Spain, Lebanon, Hungary, Chile, and Bolivia. (The Palmer Congregation has never made any public comment on the abuse or cover-up allegations, and didn’t return a comment request for this story.)

A month after the documents appeared online, McKnight received an email from an officer with the Brimfield Police Department; the Palmer Congregation had reported the theft of its documents, and wanted the perpetrator brought to justice. The officer asked McKnight about the source of the letters he had published, but McKnight had no information to give.

The officer also asked whether McKnight could connect him with one of the victims, whose case appeared to fall within Massachusetts’s statute of limitations. McKnight reached out to the victim to let her know that the police were interested in talking with her. In August, I spoke with the police officer who had contacted McKnight, and a spokesperson for the Hampden County district attorney, whose jurisdiction includes Brimfield. Both told me that their offices continue to gather information on the Palmer case, but they could neither confirm nor deny that an investigation into the alleged abuser had been opened. An investigation into the theft of the Watchtower documents is ongoing.

Six months after the leaks went public, Mark received a call from his mother, whom he hadn’t spoken with in more than a year. His father had been diagnosed with esophageal cancer, and his treatment wasn’t going well. She needed help, she said, though she didn’t expect much from her son.

Mark felt hurt, not only by his mother’s low opinion of him, but also that nobody from his old congregation had bothered to tell him about his dad. He and Kimmy immediately became involved in his parents’ lives, doing their grocery shopping, driving his father to radiation treatments, and managing his care. They mostly avoided talking about religion with Mark’s parents; to lift their spirits, Kimmy even gave them one of her favorite cats. For the first time in his adult life, Mark grew close to his parents, and Kimmy became a daughter to them.

In January 2019, Mark’s father died. Three weeks later, on a Saturday afternoon, Mark was once again sitting in the Baltimore Kingdom Hall he’d attended as a child. Though he and Kimmy had—to their great surprise—still not been disfellowshipped, they did not know what to expect. Both had become vocal Watchtower critics online and no longer bothered to hide their identities. Still, there is an unwritten rule among Witnesses that funerals are a no-shun zone. They were mostly greeted warmly, and both were glad to see some old friends. The elder giving the eulogy spoke of Jerry O’Donnell’s ever-present smile and his endearing habit of obsessive record-keeping.

Late that night, driving back to Mark’s house, I asked him about the state of the Judas documents, a subject he had put off discussing with me during his father’s illness. He said he planned to send the documents describing serious crimes to the relevant local authorities. And he was excited about more documents he expected to receive soon.

I asked him about a picture that had been on display at the funeral, a faded Polaroid showing a large group of people wading into an aboveground pool in a large, empty parking lot. He laughed. That was a picture of his parents’ baptism, in the parking lot of a stadium in Washington, D.C. Once again, he told me about how his parents became Jehovah’s Witnesses after a local couple told them the end of the world was coming. This time, though, he told the story with a tone of forgiveness I hadn’t heard before. “You have to remember,” he said, “they were talked into this, too.”

. I can see this going over especially big in the child cancer wards - bald is not only beautiful but a trait of super intelligence! I'm thinking the transparent head exposing a high-tech inner brain is the main thing. Cancer kids can embrace the insinuation that super powers aren't just for those with hair! And one wonders if this will set off a trend of kids demanding shaved heads?!! Although I jest, doesn't presenting child facsimiles with no hair have a dehumanizing effect?

. I can see this going over especially big in the child cancer wards - bald is not only beautiful but a trait of super intelligence! I'm thinking the transparent head exposing a high-tech inner brain is the main thing. Cancer kids can embrace the insinuation that super powers aren't just for those with hair! And one wonders if this will set off a trend of kids demanding shaved heads?!! Although I jest, doesn't presenting child facsimiles with no hair have a dehumanizing effect?

for the arrests -

for the arrests -  for the crime.

for the crime.