In the last days, we have heard that Merkel knew it was preparing for war:

swentr.site

swentr.site

But one could also go back and think of another time when the problem was not solved, from a German, British, US perspective. Below is a translation of a German article, minus the many portraits in the article, about the events prior to the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941:

Merkel confirms Ukraine peace deal was a ploy

The former German chancellor has admitted the Minsk ceasefire was arranged to buy Ukraine time to prepare for war with Russia

"the problem had not been solved" Merkel said referring to recent problems.“[Ukraine] used this time to get stronger, as you can see today,” Merkel continued. “The Ukraine of 2014/15 is not the Ukraine of today. As you saw in the battle for Debaltsevo in early 2015, [Russian President Vladimir] Putin could easily have overrun them at the time. And I very much doubt that the NATO countries could have done as much then as they do now to help Ukraine.”

The defeat at Debaltsevo resulted in the second Minsk protocol being signed in February 2015. Merkel said that it was “clear to all of us that the conflict was frozen, that the problem had not been solved, but that gave Ukraine valuable time.”

But one could also go back and think of another time when the problem was not solved, from a German, British, US perspective. Below is a translation of a German article, minus the many portraits in the article, about the events prior to the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941:

That is the main point, but for context, the rest of the article is machine translated and article links inserted, even if they lead to German texts.SECOND WORLD WAR

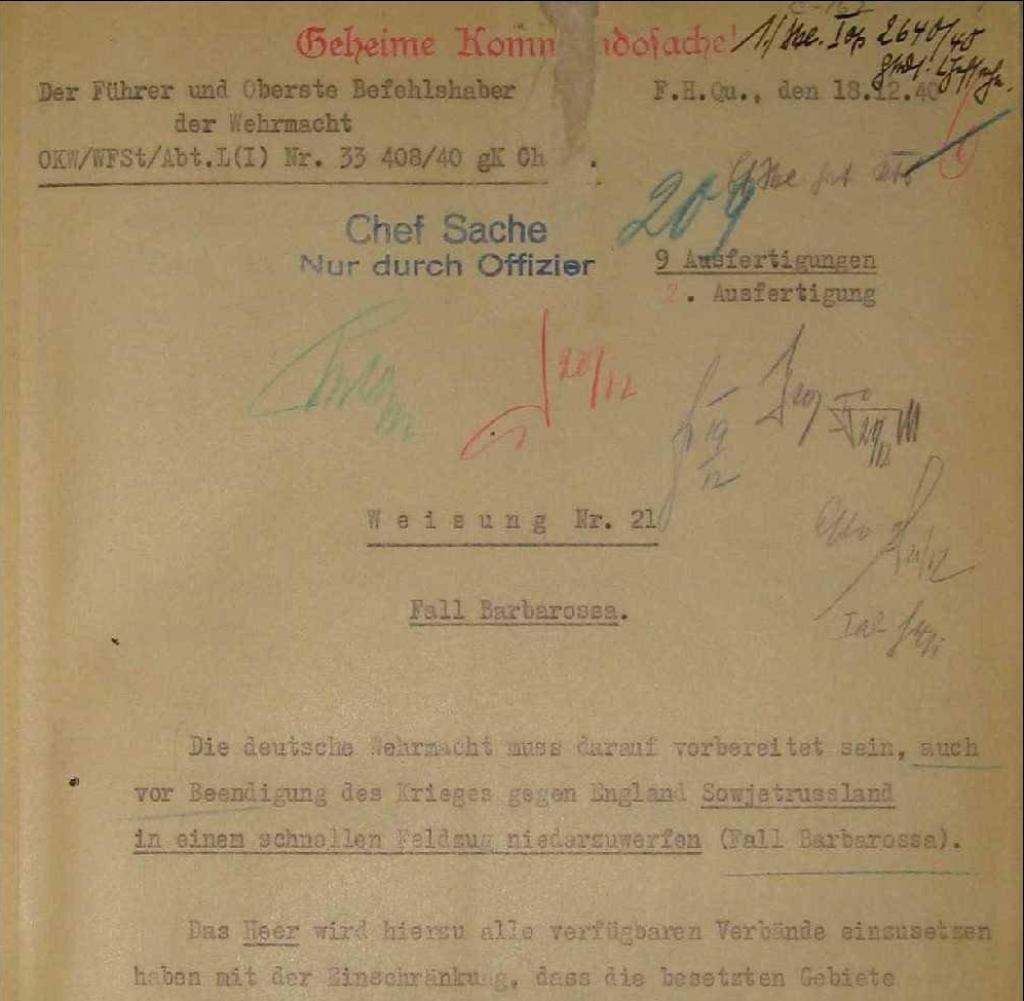

'CASE BARBAROSSA'

'The faster we crush Russia, the better!'

On December 18, 1940, Hitler issued his top-secret Directive No. 21, the order to attack the Soviet Union. Just one day later he had to receive Stalin's new ambassador in Berlin for small talk.

Published on 18.12.2020 | Reading time: 5 minutes

By Sven Felix Kellerhoff

Senior Editor History

The conversation was short; an absolute must: on the afternoon of December 19, 1940, Adolf Hitler received the new ambassador of the Soviet Union in Berlin, Vladimir Dekanosow, in his study in the New Reich Chancellery. As head of state, it was one of the tasks of the “Führer and Reich Chancellor” to accept letters of credence from diplomats. Therefore, in addition to Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, Otto Meissner was also present, as head of the Presidential Chancellery to monitor compliance with diplomatic practices.

Hitler had little to discuss with his guest, who had also been deputy foreign minister of the USSR but had previously made a career as an NKVD functionary. Because just one day before the meeting with Dekanosov, Hitler had issued his directive No. 21 as a 'Secret Command Matter'. The first sentence read: 'The German Wehrmacht must be prepared to throw down Soviet Russia in a quick campaign before the end of the war against England ('Barbarossa case').' The preparations should, 'if not already done', begin now and be completed by May 15, 1941.

Russia wanted NATO to remove themselves to pre-1997 borders. NATO did not and here we are today, but on the contrary, it has pressed east and still does.Although the highest level of secrecy automatically applied, as was the case for all 'Führer Instructions', this order, which was issued in just nine copies, still specifically stipulated: 'The number of officers to be brought in at an early stage for the preparatory work is to be kept as small as possible; other employees are to be briefed as late as possible and only to the extent required for the work of each individual.'

Because otherwise there is a risk 'that if our preparations become known, the time for which they will be carried out has not yet been set, there will be serious political and military disadvantages'. In order to protect confidentiality even better, Hitler himself ordered concealment measures internally: 'All orders to be given by the Commanders-in-Chief on the basis of this directive must be clearly coordinated to the effect that these are precautionary measures in the event that Russia changes its previous attitude towards us should.' Furthermore, 'decisive importance' should be placed on 'that the intention of an attack is not recognizable'.

Of course, in view of this topic, which occupied Hitler intensely in mid-December 1940, the meeting with Dekanosov did not fit into the schedule. Nonetheless, receiving the ambassador was inevitable in order to maintain the camouflage of one's ambitions.

To make matters worse, the German ambassador in Moscow, Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg, was simultaneously pushing for an improvement in relations with the Soviet Union. On December 18 he met with Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the next day with Deputy Prime Minister Anastas Mikoyan. Both CPSU officials tried to clear up the last differences of opinion about another German-Soviet economic agreement.

But Hitler no longer had any real interest in that. The attack on the Soviet Union had been one of his fixed goals since 1924, when he had raved about it in his pamphlet Mein Kampf. A few days after his appointment as Reich Chancellor, on February 3, 1933, he had confirmed this goal to the generals of the Reichswehr - it was about 'living space' that had to be conquered 'with armed hands,' 'probably in the east'. On July 31, 1940, he said to the army command, according to a note by Chief of Staff Franz Halder: 'In the course of this conflict, Russia must be dealt with. Spring 1941. The sooner we crush Russia, the better!”

But did Hitler really mean it? Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch, as Commander-in-Chief of the Army one of the four highest military officers in the Wehrmacht, could not imagine that. On the same December 18, 1940 on which the instructions for the “Barbarossa case” were issued to him, he instructed the army adjutant in the Führer’s headquarters, Major Gerhard Engel, “to find out whether F. (i.e. ‘Führer’, ed .) actually want to go to arms or just bluff'.

Engel did as he was told and wrote down: “I am convinced that F. himself does not yet know how to proceed. Mistrustful of his own military leadership, ambiguity about Russian strength, disappointment about the harshness of the English keep F. busy.”

At the same time, however, Engel stated that Hitler had 'repeatedly' emphasized that he 'reserved all decisions'. Foreign Minister Molotov's visit to Berlin in November 1940 showed 'that Russia wants to lay hands on Europe'. A remarkable admission followed about the German-Soviet non-aggression treaty, which had been concluded only a year and a half earlier: 'The pact was never honest, because the abysses of the world view are deep.'

Apparently Engel informed Brauchitsch verbally of his impressions, as did Curt Siewert, the Operations Officer on the Commander-in-Chief's staff, and indirectly, through another officer, the Chief of Staff Franz Halder. As early as the evening of December 18, 1940, numerous officers knew about Directive No. 21 and its contents, in addition to the commanders-in-chief who were actually addressed.

There was also more direct opposition than Brauchitsch's inquiry. At the earliest opportunity, on the afternoon of December 27, 1940, Hitler received the Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, Erich Raeder, at his request. The Grand Admiral emphasized that the war against Great Britain 'must be the urgent need of the hour' and expressed 'grave concerns about the Russian campaign before England was defeated'.

However, Hitler was not interested in these objections. With the “current political development” “the last continental opponent must be eliminated under all circumstances before he can join forces with England”. Therefore, the army must 'receive the necessary strength'. Only after the victory against the USSR would 'full concentration on the air force and navy be possible'.

Raeder's adjutant responsible for this recording added: 'The Führer's point of view is therefore the opposite of that of the Commander-in-Chief of the Navy.' Either Hitler had put his doubts aside over Christmas - or he never had any, contrary to Gerhard Engels' impression.