Audio Read Included:

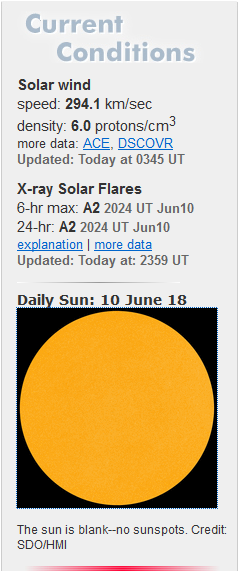

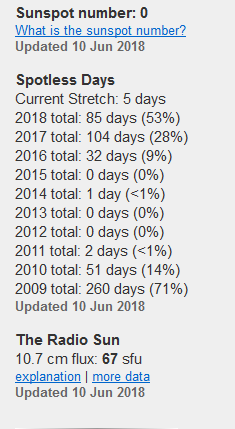

There’s something strange going on with the sun. The theory—admittedly a controversial one—is that we’re entering a grand minimum, in which the sun’s spot cycle fizzles out and cosmic radiation becomes more pervasive. We haven’t seen one since the

Space Age began.

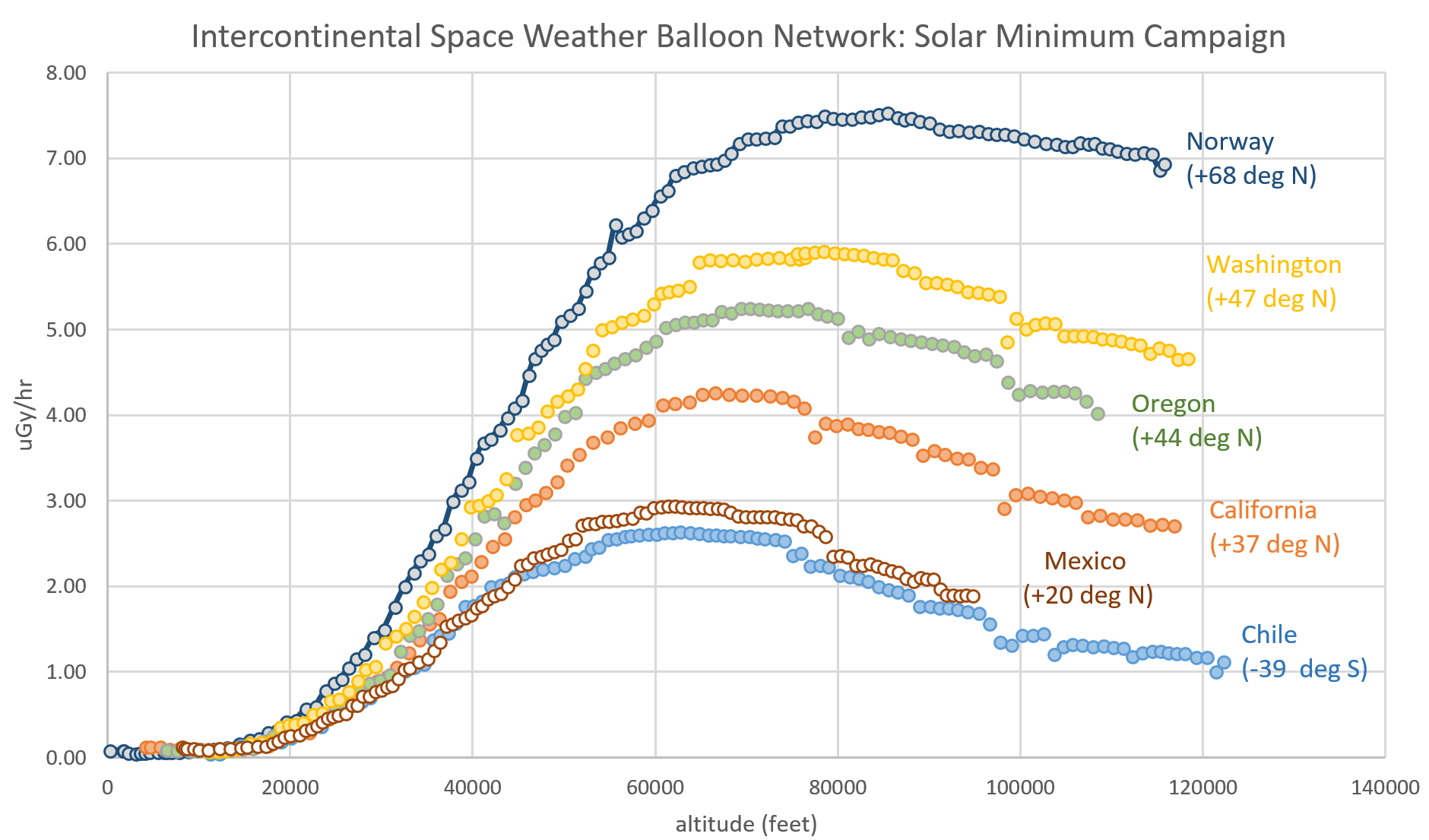

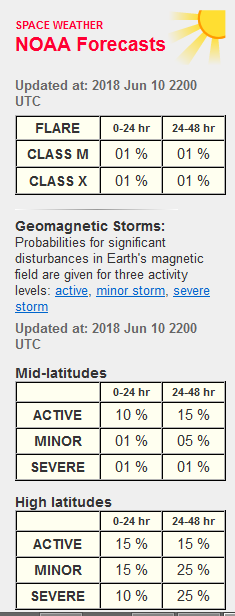

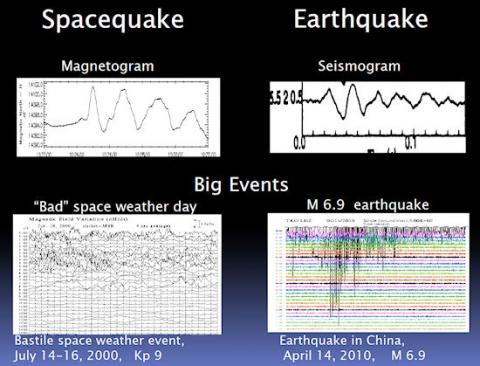

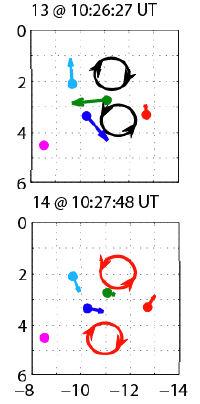

Sunspots are areas where “intense magnetic flux” has pushed up to the star’s surface, manifesting in storms whose numbers wax and wane over an 11-year cycle. At their most active, they boost the sun’s magnetic field, which envelops planets and protects them from the perils of galactic cosmic rays—charged particles from long-dead stars. Periodically, the sunspot cycle seems to fade entirely, and few or no spots show up for decades. If that happens, and we find ourselves in a grand minimum, says Scott McIntosh, a solar researcher at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., the sun’s magnetic umbrella “will be made of Swiss cheese.”

“We are in a very odd cycle, and it continues to show signs it is getting progressively worse,” says Nathan Schwadron, a professor of space plasma physics at the University of New Hampshire at Durham and a primary proponent of the grand minimum theory. “It’s a weaker cycle than what we have seen throughout the Space Age.”

A grand minimum wouldn’t mean much to the average Earthling, safely enveloped by our home world’s magnetic field. But for those few souls who may venture beyond the magnetosphere, which extends about 40,000 miles toward the sun and 370,000 miles in the other direction, it would be a different story. Research has shown that exposure to space radiation (in all forms, including from the sun itself) increases astronauts’ risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer later in life. Younger astronauts are particularly susceptible, and women are more likely to get lung, breast, and thyroid cancer.

To date, only the 24 Americans who flew the Apollo moon missions from 1969 to 1972 have ever left the magnetosphere, but they didn’t encounter particularly ferocious radiation baths. “You look at the life span of the average American, and the Apollo astronauts exceed that,” says J.D. Polk, NASA’s chief health and medical officer. Those who didn’t die in accidents “lived into very old age.” Thirteen are still around. During a grand minimum, though, the level of galactic radiation would be as much as 30 percent higher than usual, leaving would-be astronauts that much more exposed. Moreover, government space agencies and private companies such as Blue Origin and SpaceX have ambitious notions of getting humans to the moon and beyond, for longer periods of time and soon.

NASA, which is hoping to send astronauts back to the moon in 2023 and Mars after that, established career limits for radiation starting in 1970. “We will more than likely exceed that for a fair percentage of the crew going to Mars and back,” says Polk. Eddie Semones, radiation health physicist for NASA at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, says that having ships with resilient and well-configured materials will be important. The agency already knows how fierce the galaxy can be, thanks to its experience with the

Voyager probes, launched in 1977 and now far beyond the sun’s magnetic shield.

Voyager 1 entered interstellar space in 2012 and is now hurtling along 13.2 billion miles from Earth and counting, while

Voyager 2 has passed 10.9 billion. “We know what the field is out there,” Semones says. “That is the worst it would be.”

The

Orion, the ship NASA wants to use for its proposed moon mission, was built with integrated warning systems. At a meeting in Westminster, Colo., in April, solar scientists got a preview of how a live crew might fare in the event of a radiation spike. A short video clip revealed a warning system that’s both toddler-certified and scientifically sound: Following an alarm, crew members would empty the

Orion’s closets of equipment, then climb inside and pile as much stuff as possible onto themselves. The expected exposure level could drop by half, Semones says, if “you’re hunkered down low near the heat shield in the compartment in the stowage bays.” The mission could continue, though the future health risks would remain.

Just how big a problem cosmic radiation will be is an open question. Schwadron’s grand minimum theory has gained some traction among scholars, if not wide acceptance. At the meeting of solar scientists in Colorado, McIntosh asked those who supported the hypothesis to raise their hands. His own hand shot up in support, as did a few others’, but most in the audience were skeptical. Grand minimums are easier to observe than to predict.

They’ve also become a sensitive topic, thanks to an event known as the Maunder Minimum, which took place from 1645 to 1715, according to extrapolations of measurements from the day. Some contemporary opponents of policies to address climate change have argued that the Maunder Minimum caused a mini-ice age in Europe around that time. They argue that a similar event today would drastically drop Earth’s temperatures, and so the universe has us covered. Schwadron says he wouldn’t make that bet. “There has not been any definitive evidence that the cold climate in Europe was caused by the Maunder Minimum,” he points out.

We may know more about whether a grand minimum has arrived by the mid-2020s, when the current sunspot cycle reaches its expected peak. Lisa Simonsen, a space radiation element scientist at NASA, says that if one comes to pass, the agency can plan for it. The missions would simply be designed and tested based on whatever conditions might be encountered. NASA does have a few

potential tricks up its sleeve, beyond the duck-and-cover method. Advanced materials called hydrogenated boron nitride nanotubes, or hydrogenated BNNTs, could be used to improve shielding. The agency has also considered whether magnetic force fields can be formed around ships.

There could even be some advantage to a grand minimum. Cosmic rays are fairly stable—and therefore predictable—over long periods of time; high sunspot levels, by contrast, can mean spikes in solar radiation, including possible coronal mass ejections. Such ejections come with little advance warning, and for a crew in outer space, one would likely be an emergency in the making. Cosmic radiation is the devil NASA can know.