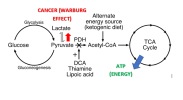

I recently finished reading a book called "Thiamine Deficiency Disease, Dysautonomia, and High Calorie Malnutrition" by Dr Derrick Lonsdale and Chandler Marrs, PhD. It is a semi-academic text on the underlying biochemistry of thiamine metabolism, and how thiamine sufficiency is essential for all things related to intracellular energy production. Thiamine is an essential B vitamin, known as vitamin B1, and is involved as a cofactor for several enzyme complexes involved in the citric acid cycle, amino acid breakdown, and neurotransmitter synthesis. It lies at the top of the citric acid cycle, as a cofactor for the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. If there is not enough B1, energy is shunted toward anaerobic (non-oxidative) metabolism. It is also critical for maintaining the function of the myelin sheath and proper signals in the nervous system.

The authors of this book elaborate on the "bioenergetic" theory of disease, which basically states that most, if not all diseases, are driven by a deficit of useable energy. When energy is low, ordinary maintenance and cellular function is disrupted and suboptimal back-up mechanisms are relied upon as mainstay.

End stage thiamine deficiency was commonly known to manifest as "beriberi", Wernicke's encephalopathy, and Korsakoff's psychosis:

[QUOTE author=Wikipedia]Symptoms of beriberi include weight loss, emotional disturbances, impaired sensory perception, weakness and pain in the limbs, and periods of irregular heart rate. Edema (swelling of bodily tissues) is common. It may increase the amount of lactic acid and pyruvic acid within the blood. In advanced cases, the disease may cause high-output cardiac failure and death.

Symptoms may occur concurrently with those of Wernicke's encephalopathy, a primarily neurological thiamine-deficiency related condition.

Beriberi is divided into four categories as follows. The first three are historical and the fourth, gastrointestinal beriberi, was recognized in 2004:

However, Dr Lonsdale's work at the Cleveland Clinic over the past 40 years demonstrated that thiamine deficiency was extremely common in a whole host of people who suffered from a wide variety of diseases. This was especially true for nervous system, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal issues. The funny thing is, I was never taught that thiamine is so commonly deficient in people who are sick. This topic seems to be vastly under recognized.

The over-consumption of simple carbohydrates, sugars, and foods which contain thiamine-degrading enzymes (thiaminases - tea and coffee), rapidly depletes thiamine. An easy way to conceptualize this follows: For each molecule of glucose that is used to produce energy, the body needs to use thiamine. When excess glucose is consumed without the extra addition of thiamine, then the stores of thiamine are unable to match the requirement. This leads to dysfunctional metabolism of glucose, where glucose is converted into lactate in the cell fluid, rather than entering the mitochondria.

Based on my research over the past few months, there seems to be several factors which can potentially drive a thiamine deficiency (off of the top of my head):

- Excessive refined carbohydrate / sugar intake

- Gut dysbiosis/malabsorption/gut inflammation

- Excessive hydrogen sulfide gas production in the gut (smelly flatulence resembling rotten egg/sulfurous vegetable smell) - some animal research suggests that hydrogen sulfide degrades thiamine in the gut

- Some pharmaceutical medications (Metformin, oral contraceptive pill etc)

- Tea/coffee with meals

- Excessive oxalates in the diet/or endogenous production of oxalate

Thiamine can be used therapeutically in a wide range of conditions. Dr Lonsdale successfully treat many cases of nervous system disorder such as Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, dysautonomias, insomnia, depression, schizophrenia, along with cardiovascular disease, excessive vomiting, gut issues, and many more. There is research suggesting that thiamine can be used for diabetes (both type 1 and 2), fibromyalgia, and other conditions which I will lay out in another post below.

Below is a very good introduction to the topic by one of the authors of the book:

The authors of this book elaborate on the "bioenergetic" theory of disease, which basically states that most, if not all diseases, are driven by a deficit of useable energy. When energy is low, ordinary maintenance and cellular function is disrupted and suboptimal back-up mechanisms are relied upon as mainstay.

End stage thiamine deficiency was commonly known to manifest as "beriberi", Wernicke's encephalopathy, and Korsakoff's psychosis:

[QUOTE author=Wikipedia]Symptoms of beriberi include weight loss, emotional disturbances, impaired sensory perception, weakness and pain in the limbs, and periods of irregular heart rate. Edema (swelling of bodily tissues) is common. It may increase the amount of lactic acid and pyruvic acid within the blood. In advanced cases, the disease may cause high-output cardiac failure and death.

Symptoms may occur concurrently with those of Wernicke's encephalopathy, a primarily neurological thiamine-deficiency related condition.

Beriberi is divided into four categories as follows. The first three are historical and the fourth, gastrointestinal beriberi, was recognized in 2004:

- Dry beriberi specially affects the peripheral nervous system.

- Wet beriberi specially affects the cardiovascular system and other bodily systems.

- Infantile beriberi affects the babies of malnourished mothers.

- Gastrointestinal beriberi affects the digestive system and other bodily systems.[/QUOTE]

However, Dr Lonsdale's work at the Cleveland Clinic over the past 40 years demonstrated that thiamine deficiency was extremely common in a whole host of people who suffered from a wide variety of diseases. This was especially true for nervous system, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal issues. The funny thing is, I was never taught that thiamine is so commonly deficient in people who are sick. This topic seems to be vastly under recognized.

The over-consumption of simple carbohydrates, sugars, and foods which contain thiamine-degrading enzymes (thiaminases - tea and coffee), rapidly depletes thiamine. An easy way to conceptualize this follows: For each molecule of glucose that is used to produce energy, the body needs to use thiamine. When excess glucose is consumed without the extra addition of thiamine, then the stores of thiamine are unable to match the requirement. This leads to dysfunctional metabolism of glucose, where glucose is converted into lactate in the cell fluid, rather than entering the mitochondria.

Based on my research over the past few months, there seems to be several factors which can potentially drive a thiamine deficiency (off of the top of my head):

- Excessive refined carbohydrate / sugar intake

- Gut dysbiosis/malabsorption/gut inflammation

- Excessive hydrogen sulfide gas production in the gut (smelly flatulence resembling rotten egg/sulfurous vegetable smell) - some animal research suggests that hydrogen sulfide degrades thiamine in the gut

- Some pharmaceutical medications (Metformin, oral contraceptive pill etc)

- Tea/coffee with meals

- Excessive oxalates in the diet/or endogenous production of oxalate

Thiamine can be used therapeutically in a wide range of conditions. Dr Lonsdale successfully treat many cases of nervous system disorder such as Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, dysautonomias, insomnia, depression, schizophrenia, along with cardiovascular disease, excessive vomiting, gut issues, and many more. There is research suggesting that thiamine can be used for diabetes (both type 1 and 2), fibromyalgia, and other conditions which I will lay out in another post below.

Below is a very good introduction to the topic by one of the authors of the book:

Beriberi, the Great Imitator

Because of some unusual clinical experiences as a pediatrician, I have published a number of articles in the medical press on thiamine, also known as vitamin B1. Deficiency of this vitamin is the primary cause of the disease called beriberi. It took many years before the simple explanation for this incredibly complex disease became known. A group of scientists from Japan called the “Vitamin B research committee of Japan” wrote and published the Review of Japanese Literature on Beriberi and Thiamine, in 1965. It was translated into English subsequently to pass the information about beriberi to people in the West who were considered to be ignorant of this disease. A book published in 1965 on a medical subject that few recall may be regarded in the modern world as being out of date and of historical interest only, however, it has been said that “Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it”. And repeat it, we are.

Beriberi is one of the nutritional diseases that is regarded as being conquered. It is rarely considered as a cause of disease in any well-developed country, including America. In what follows, are extractions from this book that are pertinent to many of today’s chronic health issues. It appears that thiamine deficiency is making a comeback but it is rarely considered as a possibility.

The History of Beriberi and Thiamine Deficiency

Beriberi has existed in Japan from antiquity and records can be found in documents as early as 808. Between 1603 and 1867, city inhabitants began to eat white rice (polished by a mill). The act of taking the rice to a mill reflected an improved affluence since white rice looked better on the table and people were demonstrating that they could afford the mill. Now we know that thiamine and the other B vitamins are found in the cusp around the rice grain. The grain consists of starch that is metabolized as glucose and the vitamins essential to the process are in the cusp. The number of cases of beriberi in Japan reached its peak in the 1920s, after which the declining incidence was remarkable. This is when the true cause of the disease was found. Epidemics of the disease broke out in the summer months, an important point to be noted later in this article.

Early Thiamine Research

Before I go on, I want to mention an extremely important experiment that was carried out in 1936. Sir Rudolf Peters showed that there was no difference in the metabolic responses of thiamine deficient pigeon brain cells, compared with cells that were thiamine sufficient, until glucose (sugar) was added. Peters called the failure of the thiamine deficient cells to respond to the input of glucose the catatorulin effect. The reason I mention this historical experiment is because we now know that the clinical effects of thiamine deficiency can be precipitated by ingesting sugar, although these effects are insidious, usually relatively minor in character and can remain on and off for months. The symptoms, as recorded in experimental thiamine deficiency in human subjects, are often diagnosed as psychosomatic. Treated purely symptomatically and the underlying dietary cause neglected, the clinical course gives rise to much more serious symptoms that are then diagnosed as various types of chronic brain disease.

Are the Clinical Effects Relevant Today?

- Thiamine Deficiency Related Mortality. The mortality in beriberi is extremely low. In Japan the total number of deaths decreased from 26,797 in 1923 to only 447 in 1959 after the discovery of its true cause.

- Thiamine Deficiency Related Morbidity. This is another story. It describes the number of people living and suffering with the disease. In spite of the newly acquired knowledge concerning its cause, during August and September 1951, of 375 patients attending a clinic in Tokyo, 29% had at least two of the major beriberi signs. The importance of the summer months will be mentioned later.

The book records a thiamine deficiency experiment in four healthy male adults. Note that this was an experiment, not a natural occurrence of beriberi. The two are different in detail. Deficiency of the other B vitamins is involved in beriberi but thiamine deficiency dominates the picture. In the second week of the experiment, the subjects described general malaise, and a “heavy feeling” in the legs. In the third week of the experiment they complained of palpitations of the heart. Examination revealed either a slow or fast heart rate, a high systolic and low diastolic blood pressure, and an increase in some of the white blood cells. In the fourth week there was a decrease in appetite, nausea, vomiting and weight loss. Symptoms were rapidly abolished with restoration of thiamine. These are common symptoms that confront the modern physician. It is most probable that they would be diagnosed as a simple infection such as a virus and of course, they could be.

Subjective Symptoms of Naturally Occurring Beriberi

The early symptoms include general malaise, loss of strength in knee joints, “pins and needles” in arms and legs, palpitation of the heart, a sense of tightness in the chest and a “full” feeling in the upper abdomen. These are complaints heard by doctors today and are often referred to as psychosomatic, particularly when the laboratory tests are normal. Nausea and vomiting are invariably ascribed to other causes.

General Objective Symptoms of Beriberi

The mental state is not affected in the early stages of beriberi. The patient may look relatively well. The disease in Japan was more likely in a robust manual laborer. Some edema or swelling of the tissues is present also in the early stages but may be only slight and found only on the shin. Tenderness in the calf muscles may be elicited by gripping the calf muscle, but such a test is probably unlikely in a modern clinic.

In later stages, fluid is found in the pleural cavity, surrounding the heart in the pericardium and in the abdomen. Fluid in body cavities is usually ascribed to other “more modern” causes and beriberi is not likely to be considered. There may be low grade fever, usually giving rise to a search for an infection. We are all aware that such symptoms come from other causes, but a diet history might suggest that beriberi is a possibility in the differential diagnosis.

Beriberi and the Cardiovascular System

In the early stages of beriberi the patient will have palpitations of the heart on physical or mental exertion. In later stages, palpitations and breathlessness will occur even at rest. X-ray examination shows the heart to be enlarged and changes in the electrocardiogram are those seen with other heart diseases. Findings like this in the modern world would almost certainly be diagnosed as “viral myocardiopathy”.

Beriberi and the Nervous System

Polyneuritis and paralysis of nerves to the arms and legs occur in the early stages of beriberi and there are major changes in sensation including touch, pain and temperature perception. Loss of sensation in the index finger and thumb dominates the sensory loss and may easily be mistaken for carpal tunnel syndrome. “Pins and needles”, numbness or a burning sensation in the legs and toes may be experienced.

In the modern world, this would be studied by a test known as electromyography and probably attributed to other causes. A 39 year old woman is described in the book. She had lassitude (severe fatigue) and had difficulty in walking because of dizziness and shaking, common symptoms seen today by neurologists.

Beriberi and the Autonomic Nervous System

We have two nervous systems. One is called voluntary and is directed by the thinking brain that enables willpower. The autonomic system is controlled by the non-thinking lower part of the brain and is automatic. This part of the brain is peculiarly sensitive to thiamine deficiency, so dysautonomia (dys meaning abnormal and autonomia referring to the autonomic system) is the major presentation of beriberi in its early stages, interfering with our ability for continuous adaptation to the environment. Since it is automatic, body functions are normally carried out without our having to think about them.

There are two branches to the system: one is called sympathetic and the other one is called parasympathetic. The sympathetic branch is triggered by any form of physical or mental stress and prepares us for action to manage response to the stress. Sensing danger, this system activates the fight-or-flight reflex. The parasympathetic branch organizes the functions of the body at rest. As one branch is activated, the other is withdrawn, representing the Yin and Yang (extreme opposites) of adaptation.

Beriberi is characterized in its early stages by dysautonomia, appearing as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome(POTS). This well documented modern disease cannot be distinguished from beriberi except by appropriate laboratory testing for thiamine deficiency. Blood thiamine levels are usually normal in the mild to moderate deficiency state.

Examples of Dysfunction in Beriberi

The calf muscle often cramps with physical exercise. There is loss of the deep tendon reflexes in the legs. There is diminished visual acuity. Part of the eye is known as the papilla and pallor occurs in its lateral half. If this is detected by an eye doctor and the patient has neurological symptoms, a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis would certainly be entertained.

Optic neuritis is common in beriberi. Loss of sensation is greater on the front of the body, follows no specific nerve distribution and is indistinct, suggestive of “neurosis” in the modern world.

Foot and wrist drop, loss of sensation to vibration (commonly tested with a tuning fork) and stumbling on walking are all examples of symptoms that would be most likely ascribed to other causes.

Breathlessness with or without exertion would probably be ascribed to congestive heart failure of unknown cause or perhaps associated with high blood pressure, even though they might have a common cause that goes unrecognized.

The symptoms of this disease can be precipitated for the first time when some form of stress is applied to the body. This can be a simple infection such as a cold, a mild head injury, exposure to sunlight or even an inoculation, important points to consider when unexpected complications arise after a mild incident of this nature. Note the reference to sunlight and the outbreaks of beriberi in the summer months. We now know that ultraviolet light is stressful to the human body. Exposure to sunlight, even though it provides us with vitamin D as part of its beneficence, is for the fit individual. Tanning of the skin is a natural defense mechanism that exhibits the state of health.

Is Thiamine Deficiency Common in America?

My direct answer to this question is that it is indeed extremely common. There is good reason for it because sugar ingestion is so extreme and ubiquitous within the population as a whole. It is the reason that I mentioned the experiment of Rudolph Peters. Ingestion of sugar is causing widespread beriberi, masking as psychosomatic disease and dysautonomia. The symptoms and physical findings vary according to the stage of the disease. For example, a low or a high acid in the stomach can occur at different times as the effects of the disease advance. Both are associated with gastroesophageal reflux and heartburn, suggesting that the acid content is only part of the picture.

A low blood sugar can cause the symptoms of hypoglycemia, a relatively common condition. A high blood sugar can be mistaken for diabetes, both seen in varying stages of the disease.

It is extremely easy to detect thiamine deficiency by doing a test on red blood cells. Unfortunately this test is either incomplete or not performed at all by any laboratory known to me.

The lower part of the human brain that controls the autonomic nervous system is exquisitely sensitive to thiamine deficiency. It produces the same effect as a mild deprivation of oxygen. Because this is dangerous and life-threatening, the control mechanisms become much more reactive, often firing the fight-or-flight reflex that in the modern world is diagnosed as panic attacks. Oxidative stress (a deficiency or an excess of oxygen affecting cells, particularly those of the lower brain) is occurring in children and adults. It is responsible for many common conditions, including jaundice in the newborn, sudden infancy death, recurrent ear infections, tonsillitis, sinusitis, asthma, attention deficit disorder (ADD), hyperactivity, and even autism. Each of these conditions has been reported in the medical literature as related to oxidative stress. So many different diseases occurring from the same common cause is offensive to the present medical model. This model regards each of these phenomena as a separate disease entity with a specific cause for each.

Without the correct balance of glucose, oxygen and thiamine, the mitochondria (the engines of the cell) that are responsible for producing the energy of cellular function, cannot realize their potential. Because the lower brain computes our adaptation, it can be said that people with this kind of dysautonomia are maladapted to the environment. For example they cannot adjust to outside temperature, shivering and going blue when it is hot and sweating when it is cold.

So, yes, beriberi and thiamine deficiency have re-emerged. And yes, we have forgotten history and appear doomed to repeat it. When supplemental thiamine and magnesium can be so therapeutic, it is high time that the situation should be addressed more clearly by the medical profession.

Last edited: