I will try and make time. I think I have previously read the one about Hitler's genealogy. Thanks for posting this though.If you have the time and the inclination, you can take a look at Miles Mathis' view of things again...:

The Beer Hall Putsch was faked

Hitler's Genealogy

Benito Mussolini

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alton Towers, Sir Francis Bacon and the Rosicrucians

- Thread starter MJF

- Start date

The C's have confirmed that there really was a Tower of Babel, the Washington Monument's construction stemming from an inherited soul memory of the Tower (see below):

Q: (L) What did the Tower of Babel look like?

A: Looked very similar to your Washington Monument. Which re-creation is an ongoing replication of a soul memory.

But here in Argentina we have the same thing! (yes, there is Freemasonry behind it, but it deserves another section). The interesting thing here is that when the country goes through very significant moments, people massively gather there.

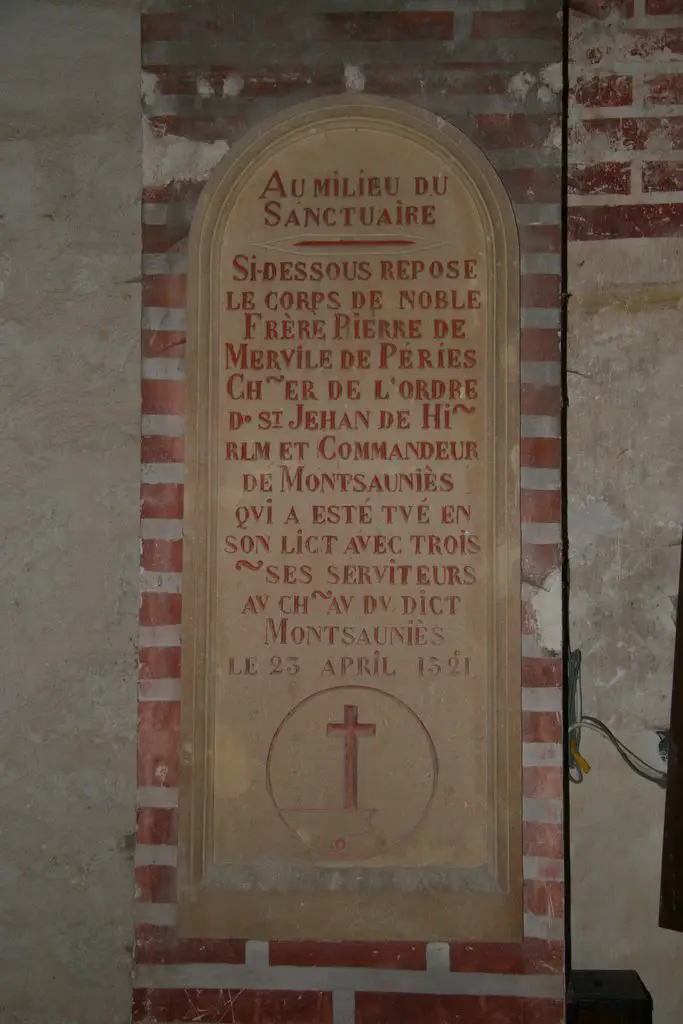

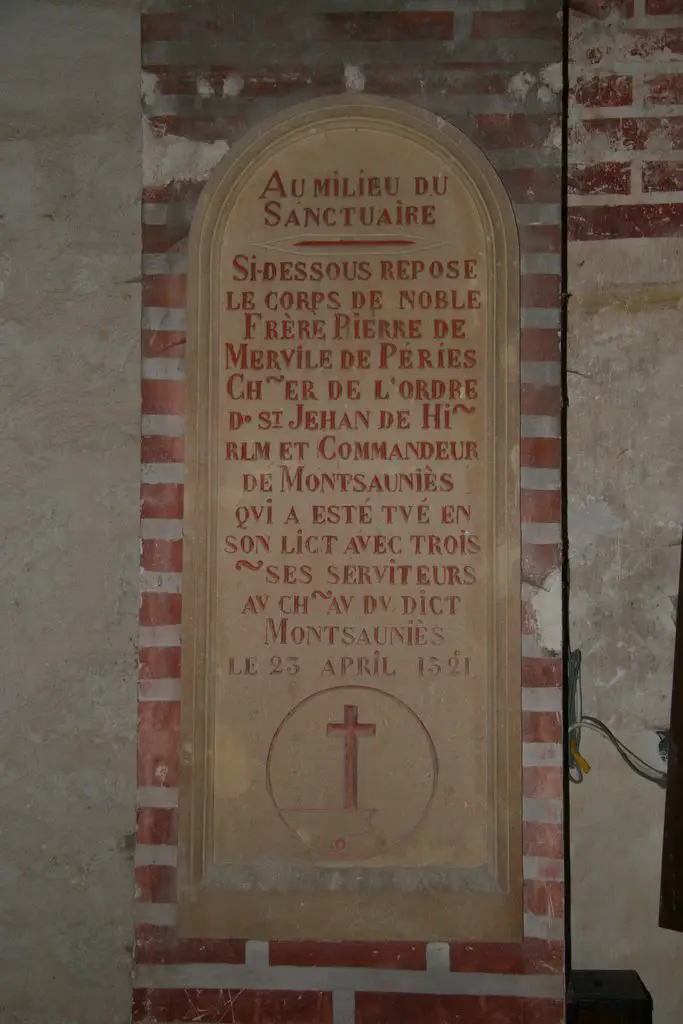

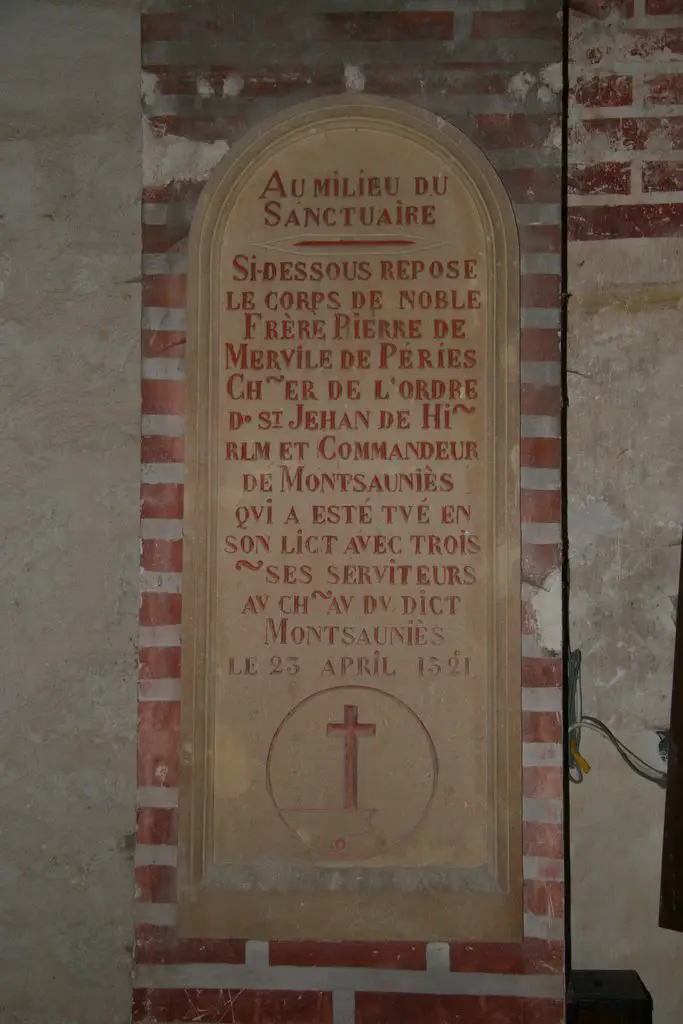

MJF, given your interest in Templars, I thought you could be interested by this church which I didn't know of but is very peculiar. It's the St Christophe church in Montsaunès. Here is what the Tourism office says about it :

The church of Saint-Christophe is a large brick building that dates back to the end of the 12th century. It has preserved its remarkable decorations which make its reputation. Indeed, two portals with finely chiseled figurations in white limestone as well as the interior painted set allow to grasp the religious and symbolic dimensions of the Templars. The capitals of the portals date back to the end of the 12th century and are among the most beautiful in Comminges. Set in stylized architectural decorations, they refer to different episodes of the New Testament. In particular, they deal with the childhood of Jesus, or with the life of certain apostles or holy martyrs (crucifixion of St Peter, stoning of St Stephen, etc.). The arch of the western portal is decorated with sculpted masks. They include, at the top, the chosen ones with calm and peaceful faces, contrasting with those of the damned with grimacing faces located at the ends.

The paintings inside the church, dating from the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century, deal with original and varied themes. They contain elements of the symbolism of the Templars, often with a complex interpretation, which has given rise to numerous esoteric decipherments. However, we can note that the vault studded with rosettes and stars probably refers to the celestial vault. On the walls of the nave are represented prophets or holy confessors sheltering under arches. More mysterious are the geometric decorations, the friezes of checkerboards or the square surmounted by a sagittarius. Or the scene of the Weighing of the Souls where a demon with a dog's head refers to the Egyptian tradition.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Some pictures:

The church of Saint-Christophe is a large brick building that dates back to the end of the 12th century. It has preserved its remarkable decorations which make its reputation. Indeed, two portals with finely chiseled figurations in white limestone as well as the interior painted set allow to grasp the religious and symbolic dimensions of the Templars. The capitals of the portals date back to the end of the 12th century and are among the most beautiful in Comminges. Set in stylized architectural decorations, they refer to different episodes of the New Testament. In particular, they deal with the childhood of Jesus, or with the life of certain apostles or holy martyrs (crucifixion of St Peter, stoning of St Stephen, etc.). The arch of the western portal is decorated with sculpted masks. They include, at the top, the chosen ones with calm and peaceful faces, contrasting with those of the damned with grimacing faces located at the ends.

The paintings inside the church, dating from the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century, deal with original and varied themes. They contain elements of the symbolism of the Templars, often with a complex interpretation, which has given rise to numerous esoteric decipherments. However, we can note that the vault studded with rosettes and stars probably refers to the celestial vault. On the walls of the nave are represented prophets or holy confessors sheltering under arches. More mysterious are the geometric decorations, the friezes of checkerboards or the square surmounted by a sagittarius. Or the scene of the Weighing of the Souls where a demon with a dog's head refers to the Egyptian tradition.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Some pictures:

MJF, given your interest in Templars, I thought you could be interested by this church which I didn't know of but is very peculiar. It's the St Christophe church in Montsaunès. Here is what the Tourism office says about it :

The church of Saint-Christophe is a large brick building that dates back to the end of the 12th century. It has preserved its remarkable decorations which make its reputation. Indeed, two portals with finely chiseled figurations in white limestone as well as the interior painted set allow to grasp the religious and symbolic dimensions of the Templars. The capitals of the portals date back to the end of the 12th century and are among the most beautiful in Comminges. Set in stylized architectural decorations, they refer to different episodes of the New Testament. In particular, they deal with the childhood of Jesus, or with the life of certain apostles or holy martyrs (crucifixion of St Peter, stoning of St Stephen, etc.). The arch of the western portal is decorated with sculpted masks. They include, at the top, the chosen ones with calm and peaceful faces, contrasting with those of the damned with grimacing faces located at the ends.

The paintings inside the church, dating from the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century, deal with original and varied themes. They contain elements of the symbolism of the Templars, often with a complex interpretation, which has given rise to numerous esoteric decipherments. However, we can note that the vault studded with rosettes and stars probably refers to the celestial vault. On the walls of the nave are represented prophets or holy confessors sheltering under arches. More mysterious are the geometric decorations, the friezes of checkerboards or the square surmounted by a sagittarius. Or the scene of the Weighing of the Souls where a demon with a dog's head refers to the Egyptian tradition.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Some pictures:

View attachment 72233

View attachment 72234

View attachment 72235

Thank you for this. It is rare to see medieval frescos like this surviving in such good condition. In England, the Puritan iconoclasts whitewashed over all church frescos and they have only re-emerged as and when redecoration work has been carried out.

The decorations in this church seem to be a real mixture of highly orthodox Catholic iconography and unorthodox, esoteric imagery, which is typical of the Templars. We see the Chi-Rho Cross representing Christ (or was it really a "Rho- Chi" sign like that of the Rosicrucian Rose-Cross) but with a snake wrapping itself around the bottom of the "Rho" figure, which could represent Satan, as the serpent in the Garden of Eden, or wisdom, as in the esoteric tradition.

Black and white checkerboard friezes were a device the Templars frequently used in their art, including on their battle flag called the Beauseant. This device has been carried over into Freemasonry, where Masonic temple floors are typically decorated with black and white square or diamond tiles, representing the movement from darkness into light.

As to the scene of the 'Weighing of the Souls' where a demon with a dog's head refers to the Egyptian tradition, this would seem to be

an image of the Egyptian god Anubis, the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine (or jackal) or a man with a canine head. One of his prominent roles was as a deity who ushered souls into the afterlife. He attended the weighing scale during the "Weighing of the Heart", in which it was determined whether a soul would be allowed to enter the realm of the dead. This role has now been assumed by Christ in Christian teaching.

The decorations in this church seem to be a real mixture of highly orthodox Catholic iconography and unorthodox, esoteric imagery, which is typical of the Templars. We see the Chi-Rho Cross representing Christ (or was it really a "Rho- Chi" sign like that of the Rosicrucian Rose-Cross) but with a snake wrapping itself around the bottom of the "Rho" figure, which could represent Satan, as the serpent in the Garden of Eden, or wisdom, as in the esoteric tradition.

Black and white checkerboard friezes were a device the Templars frequently used in their art, including on their battle flag called the Beauseant. This device has been carried over into Freemasonry, where Masonic temple floors are typically decorated with black and white square or diamond tiles, representing the movement from darkness into light.

As to the scene of the 'Weighing of the Souls' where a demon with a dog's head refers to the Egyptian tradition, this would seem to be

an image of the Egyptian god Anubis, the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine (or jackal) or a man with a canine head. One of his prominent roles was as a deity who ushered souls into the afterlife. He attended the weighing scale during the "Weighing of the Heart", in which it was determined whether a soul would be allowed to enter the realm of the dead. This role has now been assumed by Christ in Christian teaching.

Yeah, yeah. The 'bad guy' always has to be a German.Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn

See: Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn - New World Encyclopedia

Known Members:

...

- Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), German occult writer and mountaineer, founder of neo-paganism movement in Germany.

Let's see...

- Herr Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (1874 – 1965), Nepalese lover of spirits and founder of finger acrobatics in England.

In my previous post on the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, I said I would follow this up by doing a separate post on one of its most celebrated members, the Irish novelist, Bram Stoker. However, my reason for doing so is not so much his authorship of the famous vampire story Dracula but rather another of his stories, which, like Dracula, has been the subject of many horror movie depictions over the years and that is The Jewel of the Seven Stars. What Dracula is to vampire horror movies, The Jewel of the Seven Stars is to Egyptian mummy movies. However, before looking at the significance of the novel in reflecting Rosicrucian learning, I would first briefly like to look at the life of Bram Stoker.

Bram Stoker, the author of the novels ‘Dracula’ (1897) and ‘The Jewel of the Seven Stars’ (1903), among many others. Credit: public domain.

Abraham (Bram) Stoker was born on 8 November 1847 in Dublin, Ireland and was the third of seven children. He died on 20 April 1912. Although bedridden with an unknown illness until he started school at the age of seven, Stoker would make a complete recovery going on to excel as an athlete at Trinity College, Dublin, which he attended from 1864 to 1870, graduating with a Batchelor of Arts Degree.

Stoker became interested in the theatre whilst a student through his friend Dr. Maunsell. While working for the Irish Civil Service, he became the theatre critic for the Dublin Evening Mail newspaper, which was co-owned by Sheridan Le Fanu (1814 – 1873) an Irish writer of Gothic tales, mystery novels, and horror fiction. Le Fanu was also a leading ghost story writer of his time. Perhaps most relevant to us as regards his influence on Stoker, was the fact that Le Fanu wrote the lesbian vampire novella Carmilla, which may have been a major inspiration for Dracula.

Theatre critics were held in low esteem at the time, but Stoker attracted notice by the quality of his reviews. In December 1876, he gave a favourable review of Henry Irving's Hamlet at the Theatre Royal in Dublin. Irving invited Stoker for dinner at the Shelbourne Hotel where he was staying, and they became firm friends. Stoker also wrote stories, and "Crystal Cup" was published by the London Society in 1872, followed by "The Chain of Destiny" in four parts in The Shamrock. In 1876, while a civil servant in Dublin, Stoker wrote the non-fiction book The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland (published 1879), which remained a standard work. After marriage to Florence Balcombe in 1878, Stoker moved with his wife to London where he became first acting manager and then business manager of Henry Irving's Lyceum Theatre, London, a post he would hold for 27 years. For those who may not be aware. Henry Irving was one of the most celebrated Shakespearean actors of his day, comparable in status to Lord Laurence Olivier in the 20th Century and Sir Anthony Hopkins in our own age.

The collaboration with Henry Irving was important for Stoker and through him, he became involved in London's high society, where he met American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (the author of the Sherlock Holmes novels as well as being a leading spiritualist, to whom Stoker was apparently distantly related). Working for Irving, the most famous actor of his time, and managing one of the most successful theatres in London made Stoker a notable if busy man. He was dedicated to Irving and his memoirs show he idolised him. In London, Stoker also met the novelist Hall Caine, who became one of his closest friends. Stoker would subsequently dedicate Dracula to Caine, under the nickname 'Hommy-Beg'. Interestingly, both men shared an interest in mesmerism (aka 'magnetism' - as distinct from hypnotism).

In the course of Irving's tours, Stoker travelled the world, although he never visited Eastern Europe, the setting for his most famous novel. Stoker enjoyed the United States, where Irving was popular. With Irving he was invited twice to the White House, and knew Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. Stoker set two of his novels in America, and used Americans as characters, the most notable being Quincey Morris. He also met one of his literary idols, Walt Whitman, having written to him in 1872 an extraordinary letter that some have interpreted as the expression of a deeply-suppressed homosexuality.

Stoker enjoyed travelling, particularly to Cruden Bay in Scotland where he set two of his novels. However, it was during a visit in 1890 to the English coastal town of Whitby in East Yorkshire that Stoker drew inspiration for writing Dracula. Before writing Dracula, Stoker met Ármin Vámbéry, a Hungarian-Jewish writer and traveller (born in what is now Slovakia). Dracula likely emerged from Vámbéry's dark stories of the Carpathian Mountains. However this claim has been challenged by many including Professor Elizabeth Miller. She has stated, “The only comment about the subject matter of the talk was that Vambery 'spoke loudly against Russian aggression. There had been nothing in their conversations about the "tales of the terrible Dracula" that are supposed to have "inspired Stoker to equate his vampire-protagonist with the long-dead tyrant [i.e., Vlad Dracul or Vlad the Impaler]." At any rate, by this time, Stoker's novel was well underway, and he was already using the name Dracula for his vampire. Stoker then spent several years researching Central and East European folklore and mythological stories of vampires.

The 1972 book In Search of Dracula by Radu Florescu and Raymond McNally claimed that the Count in Stoker's novel was based on Vlad III Dracula. However, according to Elizabeth Miller, Stoker borrowed only the name and "scraps of miscellaneous information" about Romanian history; further, there are no comments about Vlad III in the author's working notes.

Dracula is an epistolary novel, written as a collection of realistic but completely fictional diary entries, telegrams, letters, ship's logs, and newspaper clippings, all of which added a level of detailed realism to the story, a skill which Stoker had developed as a newspaper writer. At the time of its publication, Dracula was considered a "straightforward horror novel" based on imaginary creations of supernatural life. "It gave form to a universal fantasy and became a part of popular culture." The original 541-page typescript of Dracula was believed to have been lost until it was found in a barn in north-western Pennsylvania in the early 1980s. Handwritten on the title page was "THE UN-DEAD", which suggests Stoker changed it at the last minute to Dracula prior to its publication.

In the Wikipedia entry for Stoker (from which much of the above has been gleaned - see: Bram Stoker - Wikipedia), it states:

"Stoker believed in progress and took a keen interest in science and science-based medicine. Some of Stoker's novels represent early examples of science fiction, such as The Lady of the Shroud (1909). He had a writer's interest in the occult, notably mesmerism, but despised fraud and believed in the superiority of the scientific method over superstition. Stoker counted among his friends J. W. Brodie-Innis, a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and hired member Pamela Colman Smith as an artist for the Lyceum Theatre, but no evidence suggests that Stoker ever joined the Order himself. Although Irving was an active Freemason, no evidence has been found of Stoker taking part in Masonic activities in London. The Grand Lodge of Ireland also has no record of his membership."

However, no evidence of membership does not automatically mean that he was not a member or participant in the Order, since, as we have learned, the Rosicrucians, unlike the Freemasons, do not keep records of their membership. Moreover, even if he was not a member of the Order himself, the fact that he had close contact with people who were, such as those named above, might indicate that many of the Order's beliefs, tenets and teachings may have rubbed off on him and permeated his thinking, which then found its way into his writing.

The Jewel of the Seven Stars

Having covered Stoker's life and his connections, I would like to turn to an article I referred to in my earlier post by the writer and researcher Andrew Collins called Goddess of the Seven Stars: The Rebirth of Sobekneferu.

Bram Stoker, the author of the novels ‘Dracula’ (1897) and ‘The Jewel of the Seven Stars’ (1903), among many others. Credit: public domain.

Abraham (Bram) Stoker was born on 8 November 1847 in Dublin, Ireland and was the third of seven children. He died on 20 April 1912. Although bedridden with an unknown illness until he started school at the age of seven, Stoker would make a complete recovery going on to excel as an athlete at Trinity College, Dublin, which he attended from 1864 to 1870, graduating with a Batchelor of Arts Degree.

Stoker became interested in the theatre whilst a student through his friend Dr. Maunsell. While working for the Irish Civil Service, he became the theatre critic for the Dublin Evening Mail newspaper, which was co-owned by Sheridan Le Fanu (1814 – 1873) an Irish writer of Gothic tales, mystery novels, and horror fiction. Le Fanu was also a leading ghost story writer of his time. Perhaps most relevant to us as regards his influence on Stoker, was the fact that Le Fanu wrote the lesbian vampire novella Carmilla, which may have been a major inspiration for Dracula.

Theatre critics were held in low esteem at the time, but Stoker attracted notice by the quality of his reviews. In December 1876, he gave a favourable review of Henry Irving's Hamlet at the Theatre Royal in Dublin. Irving invited Stoker for dinner at the Shelbourne Hotel where he was staying, and they became firm friends. Stoker also wrote stories, and "Crystal Cup" was published by the London Society in 1872, followed by "The Chain of Destiny" in four parts in The Shamrock. In 1876, while a civil servant in Dublin, Stoker wrote the non-fiction book The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland (published 1879), which remained a standard work. After marriage to Florence Balcombe in 1878, Stoker moved with his wife to London where he became first acting manager and then business manager of Henry Irving's Lyceum Theatre, London, a post he would hold for 27 years. For those who may not be aware. Henry Irving was one of the most celebrated Shakespearean actors of his day, comparable in status to Lord Laurence Olivier in the 20th Century and Sir Anthony Hopkins in our own age.

The collaboration with Henry Irving was important for Stoker and through him, he became involved in London's high society, where he met American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (the author of the Sherlock Holmes novels as well as being a leading spiritualist, to whom Stoker was apparently distantly related). Working for Irving, the most famous actor of his time, and managing one of the most successful theatres in London made Stoker a notable if busy man. He was dedicated to Irving and his memoirs show he idolised him. In London, Stoker also met the novelist Hall Caine, who became one of his closest friends. Stoker would subsequently dedicate Dracula to Caine, under the nickname 'Hommy-Beg'. Interestingly, both men shared an interest in mesmerism (aka 'magnetism' - as distinct from hypnotism).

In the course of Irving's tours, Stoker travelled the world, although he never visited Eastern Europe, the setting for his most famous novel. Stoker enjoyed the United States, where Irving was popular. With Irving he was invited twice to the White House, and knew Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. Stoker set two of his novels in America, and used Americans as characters, the most notable being Quincey Morris. He also met one of his literary idols, Walt Whitman, having written to him in 1872 an extraordinary letter that some have interpreted as the expression of a deeply-suppressed homosexuality.

Stoker enjoyed travelling, particularly to Cruden Bay in Scotland where he set two of his novels. However, it was during a visit in 1890 to the English coastal town of Whitby in East Yorkshire that Stoker drew inspiration for writing Dracula. Before writing Dracula, Stoker met Ármin Vámbéry, a Hungarian-Jewish writer and traveller (born in what is now Slovakia). Dracula likely emerged from Vámbéry's dark stories of the Carpathian Mountains. However this claim has been challenged by many including Professor Elizabeth Miller. She has stated, “The only comment about the subject matter of the talk was that Vambery 'spoke loudly against Russian aggression. There had been nothing in their conversations about the "tales of the terrible Dracula" that are supposed to have "inspired Stoker to equate his vampire-protagonist with the long-dead tyrant [i.e., Vlad Dracul or Vlad the Impaler]." At any rate, by this time, Stoker's novel was well underway, and he was already using the name Dracula for his vampire. Stoker then spent several years researching Central and East European folklore and mythological stories of vampires.

The 1972 book In Search of Dracula by Radu Florescu and Raymond McNally claimed that the Count in Stoker's novel was based on Vlad III Dracula. However, according to Elizabeth Miller, Stoker borrowed only the name and "scraps of miscellaneous information" about Romanian history; further, there are no comments about Vlad III in the author's working notes.

Dracula is an epistolary novel, written as a collection of realistic but completely fictional diary entries, telegrams, letters, ship's logs, and newspaper clippings, all of which added a level of detailed realism to the story, a skill which Stoker had developed as a newspaper writer. At the time of its publication, Dracula was considered a "straightforward horror novel" based on imaginary creations of supernatural life. "It gave form to a universal fantasy and became a part of popular culture." The original 541-page typescript of Dracula was believed to have been lost until it was found in a barn in north-western Pennsylvania in the early 1980s. Handwritten on the title page was "THE UN-DEAD", which suggests Stoker changed it at the last minute to Dracula prior to its publication.

In the Wikipedia entry for Stoker (from which much of the above has been gleaned - see: Bram Stoker - Wikipedia), it states:

"Stoker believed in progress and took a keen interest in science and science-based medicine. Some of Stoker's novels represent early examples of science fiction, such as The Lady of the Shroud (1909). He had a writer's interest in the occult, notably mesmerism, but despised fraud and believed in the superiority of the scientific method over superstition. Stoker counted among his friends J. W. Brodie-Innis, a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and hired member Pamela Colman Smith as an artist for the Lyceum Theatre, but no evidence suggests that Stoker ever joined the Order himself. Although Irving was an active Freemason, no evidence has been found of Stoker taking part in Masonic activities in London. The Grand Lodge of Ireland also has no record of his membership."

However, no evidence of membership does not automatically mean that he was not a member or participant in the Order, since, as we have learned, the Rosicrucians, unlike the Freemasons, do not keep records of their membership. Moreover, even if he was not a member of the Order himself, the fact that he had close contact with people who were, such as those named above, might indicate that many of the Order's beliefs, tenets and teachings may have rubbed off on him and permeated his thinking, which then found its way into his writing.

The Jewel of the Seven Stars

Having covered Stoker's life and his connections, I would like to turn to an article I referred to in my earlier post by the writer and researcher Andrew Collins called Goddess of the Seven Stars: The Rebirth of Sobekneferu.

See: Goddess of the Seven Stars: The Rebirth of Sobekneferu | Ancient Origins (ancient-origins.net)

I am reproducing Collins' article in full below, as it contains a lot of useful information on Stoker's contacts with the Golden Dawn and the possible inspirations for his story. I have, of course, already commented on those parts of Collins' article that may suggest a link between the Alpha Draconians, or Lizard beings, and the Egyptian worship of crocodile headed gods such as Sobek.

Goddess of the Seven Stars: The Rebirth of Sobekneferu

In 2017 cinema audiences were treated to the latest reboot of the classic movie franchise surrounding the resurrection of an ancient Egypt mummy. Titled, inevitably, The Mummy, and starring Tom Cruise, it was an action-packed thriller featuring an Egyptian princess named Ahmanet. She, however, was just the latest incarnation of a fictional character that appears for the first time in a novel written by celebrated Irish writer Bram Stoker (1847-1912). Entitled The Jewel of the Seven Stars, it tells the story of how an ancient Egyptian queen and sorceress named Tera is able to live again in the modern world. When first published in 1903, the book’s ending was deemed so shocking that the publisher asked for it to be replaced in all subsequent editions. Compelling new evidence today suggests that Stoker’s Queen Tera was inspired by Egypt’s first female ruler, who lived around 1800 BC. Her name was Sobekneferu (also written Neferusobek), and although she ruled for just four years at the end of the Twelfth Dynasty the repercussions of her reign were long lasting and continue to be felt today.

Egypt’s Twelfth Dynasty (circa 1991-1802 BC) came towards the end of the country’s Middle Kingdom. Four of its eight kings all bore the name Amenemhat, honouring the god Amun. This included Amenemhat III, Sobekneferu’s father, who reigned circa 1860-1814 BC. He was followed by his son Amenemhat IV, Sobeknefereu’s brother. His reign, which lasted nine years, circa 1815-1806 BC, was followed by that of his sister, Sobekneferu (Manetho, 34.7). Inscriptions bearing the name both of Amenemhat III and of Sobekneferu suggest co-regency, while some scholars have proposed that following her father’s death she entered into an incestuous marriage with her brother (Gillam, s.v. “Sobeknefru,” in Erskine et al, 2013). Beyond this everything is unclear. All we do know is that, as her name suggests, she was devoted to the crocodile god Sobek, and that both she and Sobek continued to be venerated well into the incoming Thirteenth Dynasty ( Massey, 1881, ii, 402-3 & Grant, 1975, 59 ).

Goddess of the Seven Stars: The Rebirth of Sobekneferu

In 2017 cinema audiences were treated to the latest reboot of the classic movie franchise surrounding the resurrection of an ancient Egypt mummy. Titled, inevitably, The Mummy, and starring Tom Cruise, it was an action-packed thriller featuring an Egyptian princess named Ahmanet. She, however, was just the latest incarnation of a fictional character that appears for the first time in a novel written by celebrated Irish writer Bram Stoker (1847-1912). Entitled The Jewel of the Seven Stars, it tells the story of how an ancient Egyptian queen and sorceress named Tera is able to live again in the modern world. When first published in 1903, the book’s ending was deemed so shocking that the publisher asked for it to be replaced in all subsequent editions. Compelling new evidence today suggests that Stoker’s Queen Tera was inspired by Egypt’s first female ruler, who lived around 1800 BC. Her name was Sobekneferu (also written Neferusobek), and although she ruled for just four years at the end of the Twelfth Dynasty the repercussions of her reign were long lasting and continue to be felt today.

Egypt’s Twelfth Dynasty (circa 1991-1802 BC) came towards the end of the country’s Middle Kingdom. Four of its eight kings all bore the name Amenemhat, honouring the god Amun. This included Amenemhat III, Sobekneferu’s father, who reigned circa 1860-1814 BC. He was followed by his son Amenemhat IV, Sobeknefereu’s brother. His reign, which lasted nine years, circa 1815-1806 BC, was followed by that of his sister, Sobekneferu (Manetho, 34.7). Inscriptions bearing the name both of Amenemhat III and of Sobekneferu suggest co-regency, while some scholars have proposed that following her father’s death she entered into an incestuous marriage with her brother (Gillam, s.v. “Sobeknefru,” in Erskine et al, 2013). Beyond this everything is unclear. All we do know is that, as her name suggests, she was devoted to the crocodile god Sobek, and that both she and Sobek continued to be venerated well into the incoming Thirteenth Dynasty ( Massey, 1881, ii, 402-3 & Grant, 1975, 59 ).

Bust of Sobekneferu on display in the Louvre, Paris. Credit: Wiki Commons Agreement, 2020.

The Real Queen Tera

So how do we know that Sobekneferu was the inspiration behind Stoker’s Queen Tera in The Jewel of the Seven Stars ? The story tells us she lived “forty centuries” ago and was the only daughter of King Antef, who reigned during the Eleventh Dynasty. Now, there was indeed a king named Antef who ruled during the Eleventh Dynasty, circa 2130-1991 BC. In fact, there were four kings all named Antef who reigned during this dynasty. Yet none of them had a notable daughter fitting Queen Tera’s description.

Bringing us closer to an identification of Stoker’s Queen Tera is his statement that in her tomb, “Prominence was given to the fact that she, though a Queen, claimed all the privileges of kingship and masculinity. In one place she was pictured in man’s dress, and wearing the White and Red Crowns . In the following picture she was in female dress, but still wearing the Crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt.” This is a major clue to who Queen Tera might have been, for Stoker would have been aware that Sobekneferu was the first royal female to wear the twin crowns of Upper of Lower Egypt. This was three centuries earlier than the reign of Queen Hatshepsut, who is another candidate for the true identity of Stoker’s Queen Tera (see, for instance, the introduction to Penguin New York’s 2008 edition of The Jewel of the Seven Stars by Kate Hebblethwaite). She, however, ruled Egypt as much as 500 years after the intimated “forty centuries” ago that Stoker tells us Queen Tera lived on earth.

Moreover, there is a link too between Sobekneferu and a king named Antef, her father’s name in Stoker’s novel. A king list known as the Royal Tablet of Karnak, published before Stoker wrote his book, shows a king named Antef ruling immediately after Sobekneferu, something that led some commentators of the time to suspect the two were related and perhaps even married (Macnaughton, 1932, 157). Was this Antef the inspiration behind Queen Tera’s father, who in the 1980 film adaption of Stoker’s book (see below) was actually married to his daughter?

Bringing us closer to an identification of Stoker’s Queen Tera is his statement that in her tomb, “Prominence was given to the fact that she, though a Queen, claimed all the privileges of kingship and masculinity. In one place she was pictured in man’s dress, and wearing the White and Red Crowns . In the following picture she was in female dress, but still wearing the Crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt.” This is a major clue to who Queen Tera might have been, for Stoker would have been aware that Sobekneferu was the first royal female to wear the twin crowns of Upper of Lower Egypt. This was three centuries earlier than the reign of Queen Hatshepsut, who is another candidate for the true identity of Stoker’s Queen Tera (see, for instance, the introduction to Penguin New York’s 2008 edition of The Jewel of the Seven Stars by Kate Hebblethwaite). She, however, ruled Egypt as much as 500 years after the intimated “forty centuries” ago that Stoker tells us Queen Tera lived on earth.

Moreover, there is a link too between Sobekneferu and a king named Antef, her father’s name in Stoker’s novel. A king list known as the Royal Tablet of Karnak, published before Stoker wrote his book, shows a king named Antef ruling immediately after Sobekneferu, something that led some commentators of the time to suspect the two were related and perhaps even married (Macnaughton, 1932, 157). Was this Antef the inspiration behind Queen Tera’s father, who in the 1980 film adaption of Stoker’s book (see below) was actually married to his daughter?

The cover of Bram Stoker’s first edition of The Jewel of the Seven Stars published in 1903. Credit: public domain.

Bram Stoker tells us that Queen Tera was obsessed with the stars of the northern night sky, in particular the seven stars of Ursa Major, and there is every indication that Sobekneferu was interested in this same set of stars through her veneration of the crocodile god Sobek. In ancient Egyptian astronomy the crocodile was shown climbing on the back of a female hippopotamus, or as part of a hippo-croc hybrid. This combined sky figure has been identified with the stars of Draco, the celestial dragon of Greek and Arabic sky lore ( Lull and Belmonte, 2009 ), one of the key constellations of the northern night sky. Both the crocodile and hippo have also been identified with the stars of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor ( Berio, 2014 ), which are themselves extremely close to Draco.

The Deep Bosomed One

The connection here with Sobekneferu comes from the fact that a limestone block fragment found at Hawara links her with the obscure goddess Dhdh.t (Dehdehet) ( Uphill, 2010 ), whose name means “to hang down low.” This, seemingly, is a reference to drooping breasts, implying she is the “Deep-bosomed One.” (pers. comm. with the late Terence DuQuesne). This is undoubtedly a title of Egypt’s principal hippopotamus goddess Tawaret, who was Sobek’s wife. Tawaret presided over women during childbirth and pregnancy and is shown in art with long drooping breasts. What is more, she was a patron, like Sobek, of Egypt’s Faiyum Oasis, the royal seat of Sobekneferu. She was also the concubine of Seth, the god of desert lands and foreigners, who, like Sobek, often took the form of a crocodile.

The Deep Bosomed One

The connection here with Sobekneferu comes from the fact that a limestone block fragment found at Hawara links her with the obscure goddess Dhdh.t (Dehdehet) ( Uphill, 2010 ), whose name means “to hang down low.” This, seemingly, is a reference to drooping breasts, implying she is the “Deep-bosomed One.” (pers. comm. with the late Terence DuQuesne). This is undoubtedly a title of Egypt’s principal hippopotamus goddess Tawaret, who was Sobek’s wife. Tawaret presided over women during childbirth and pregnancy and is shown in art with long drooping breasts. What is more, she was a patron, like Sobek, of Egypt’s Faiyum Oasis, the royal seat of Sobekneferu. She was also the concubine of Seth, the god of desert lands and foreigners, who, like Sobek, often took the form of a crocodile.

Head of the crocodile god from the site of the Labyrinth at Hawara. It dates to the reign of Amenemhat III.

Credit: Wiki Commons Agreement, 2020.

The hippopotamus goddess Tawaret. Was she the mysterious goddess revered by Sobekneferu?

Credit: Wiki Commons Agreement, 2020.

Credit: Wiki Commons Agreement, 2020.

The hippopotamus goddess Tawaret. Was she the mysterious goddess revered by Sobekneferu?

Credit: Wiki Commons Agreement, 2020.

Goddess of the Seven Stars

Thus, through her connections with sky figures such as the crocodile and hippopotamus, both of which are bound together eternally in the northern night sky as a sky figure composed of stars from the Greek constellations of Draco, Ursa Minor and Ursa Major, we can be pretty sure that Sobekneferu’s gaze at night would have been towards this part of the heavens. Victorian mythologist Gerald Massey (1828-1907) identified the hippo-croc sky figure of ancient Egypt as a primeval genitrix, a form of Tawaret as mother of Seth (the Greek Typhon), controlling both the turning of the heavens and the passage of time. He mentions this primordial deity several times in his two-volume work The Book of Beginnings , calling her the “goddess of the seven stars.”

More significantly, Massey singled out queen Sobekneferu as reviving this age-old “Typhonian” cult, which centred around the hippopotamus goddess Tawaret or Reret and the crocodile god as a form both of Set and of Sobek (Massey, 1881). Massey also writes that a word used to express “time” in the ancient Egyptian language is “Tera,” just like Queen Tera in Stoker’s novel. This makes it likely that, through his connection with occultists in London, Stoker became familiar with Massey’s works. Having then read about Sobekneferu’s associations with the “goddess of the seven stars,” a term more-or-less unique to Massey, he conceived of the character of Queen Tera for his novel The Jewel of the Seven Stars.

Head of an ancient Egyptian royal daughter dating to around 1850 BC and thought to show Sobekneferu. Currently in the Brooklyn Museum, New York. Credit: Rodney Hale/Andrew Collins.

The Plot (Spoiler alert!)

For those unfamiliar with The Jewel of the Seven Stars, the story recounts how Egyptologists Abel Trelawny and Eugene Corbeck uncover Tera’s sarcophagus in Egypt’s “Valley of the Sorcerers.” It is transported back to England with Tera’s coffin and mummy still intact. Years later, when Trelawny falls into a trance-like sleep for some days his daughter Margaret, born at the moment the tomb was opened, begins to transform from a demure and sweet 18-year-old woman into a powerful, confident and demanding person. It becomes clear she is being taken over by Tera's spirit, the queen having performed dark rituals to ensure her rebirth in “a land under the Northern Star,” which is the British Isles.

The sarcophagus and its precious contents are brought to a cave beneath a house in Cornwall owned by Trelawny where he, Corbeck, Margaret and her suitor Malcolm Ross attempt a “great experiment” to release the queen’s spirit from its coffin so that it might live again in the statue of an Egyptian cat! However, at the height of the ritual, as a fierce storm rages outside, all hell breaks loose. A window shatters, blowing out the lamps and plunging the cave into darkness. When a light is finally lit everyone except Malcolm appears to be dead. Seeing Margaret lying on the floor, Malcolm picks up her limp body and carries it into another room. Setting her down, he leaves her there, only to find her body missing upon his return just minutes later. In its place is Tera’s marriage robe, which the queen was found to be wearing when the mummy had been unwrapped earlier that evening. Next to it was found the titular Jewel of the Seven Stars, a finger ring containing a red stone engraved with seven stars. That’s it. That’s the end. So disturbing was this deemed by the book’s post-Victorian readership that the publisher insisted Stoker rewrite it for subsequent editions. Instead of Tera possessing Margaret’s body* and disappearing mysteriously, the evil queen is defeated, Margaret marries her suitor and all live happily ever after!

*MJF: Consider what the C's have said about walk-ins here. Could Stoker have known of this concept?

Florence Farr and the Egyptian Adept

Interestingly, the way Bram Stoker has the character of Margaret change from a somewhat feeble person to a strong empowered woman is today considered one of the first literary portrayals of what in late Victorian times was being termed the “New Woman.” This was an early role model for what would become the feminist revolution of the twentieth century. For the male dominant society of the Victorian era the growing reality of such empowered women was seen as an enormous threat to their world. It is this somewhat alarming situation that is suitably conveyed by Stoker in his portrayal of Margaret’s transformation into Queen Tera in The Jewel of the Seven Stars.

It is the reality of the strong empowered woman in Sobekneferu and her incredible achievements as a king during her lifetime that inspired Stoker’s portrayal of Margaret Trelawny as a Victorian “New Woman.” What is more, it can now help us identify the real person behind the character of Margaret Trelawny. This was almost certainly a remarkable woman named Florence Farr (1860-1917). She was a British West End actress, composer, director, and member of a well-known occult society called the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Stoker certainly corresponded with Florence Farr, and almost certainly knew her personally. Yet what’s important here is that during the 1890's Farr gained direct communication with an ancient Egyptian female spirit*. This was made through contact with a mummy in the British Museum belonging to a “chantress of Amun” named Mut-em-menu (Tully, 2018). This spirit entity, whom Farr dubbed “the Egyptian Adept,” came to be seen as a personification of her higher self, quite literally her “ka,” or “sister” self ( ka means “soul” in the ancient Egyptian language).

*MJF: Please note that Collins believes in mystical communications himself, as I have witnessed first hand when he paused during a conference I attended in London, which he was chairing, to do a meditation with the audience. However, given what we have learned of channelling through the C's, is it more likely that Farr was channelling STS forces in the same way that Maria Orsic and her fellow female trance mediums of the Vril Society (an offshoot of the Thule Society) had communicated with the so-called 'Aldebarans', who may in turn have been the STS humanoid Antareans from Orion that the C's spoke of: "Antareans were the name given by 4th density groups in contact with the Thule Society on third density Earth, before and during World War One." Incidentally, Rudolf Hess supposedly took part in one of these channelling sessions with Orsic and other members of the Thule Society in 1924.

See: Maria Orsic

The sarcophagus and its precious contents are brought to a cave beneath a house in Cornwall owned by Trelawny where he, Corbeck, Margaret and her suitor Malcolm Ross attempt a “great experiment” to release the queen’s spirit from its coffin so that it might live again in the statue of an Egyptian cat! However, at the height of the ritual, as a fierce storm rages outside, all hell breaks loose. A window shatters, blowing out the lamps and plunging the cave into darkness. When a light is finally lit everyone except Malcolm appears to be dead. Seeing Margaret lying on the floor, Malcolm picks up her limp body and carries it into another room. Setting her down, he leaves her there, only to find her body missing upon his return just minutes later. In its place is Tera’s marriage robe, which the queen was found to be wearing when the mummy had been unwrapped earlier that evening. Next to it was found the titular Jewel of the Seven Stars, a finger ring containing a red stone engraved with seven stars. That’s it. That’s the end. So disturbing was this deemed by the book’s post-Victorian readership that the publisher insisted Stoker rewrite it for subsequent editions. Instead of Tera possessing Margaret’s body* and disappearing mysteriously, the evil queen is defeated, Margaret marries her suitor and all live happily ever after!

*MJF: Consider what the C's have said about walk-ins here. Could Stoker have known of this concept?

Florence Farr and the Egyptian Adept

Interestingly, the way Bram Stoker has the character of Margaret change from a somewhat feeble person to a strong empowered woman is today considered one of the first literary portrayals of what in late Victorian times was being termed the “New Woman.” This was an early role model for what would become the feminist revolution of the twentieth century. For the male dominant society of the Victorian era the growing reality of such empowered women was seen as an enormous threat to their world. It is this somewhat alarming situation that is suitably conveyed by Stoker in his portrayal of Margaret’s transformation into Queen Tera in The Jewel of the Seven Stars.

It is the reality of the strong empowered woman in Sobekneferu and her incredible achievements as a king during her lifetime that inspired Stoker’s portrayal of Margaret Trelawny as a Victorian “New Woman.” What is more, it can now help us identify the real person behind the character of Margaret Trelawny. This was almost certainly a remarkable woman named Florence Farr (1860-1917). She was a British West End actress, composer, director, and member of a well-known occult society called the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Stoker certainly corresponded with Florence Farr, and almost certainly knew her personally. Yet what’s important here is that during the 1890's Farr gained direct communication with an ancient Egyptian female spirit*. This was made through contact with a mummy in the British Museum belonging to a “chantress of Amun” named Mut-em-menu (Tully, 2018). This spirit entity, whom Farr dubbed “the Egyptian Adept,” came to be seen as a personification of her higher self, quite literally her “ka,” or “sister” self ( ka means “soul” in the ancient Egyptian language).

*MJF: Please note that Collins believes in mystical communications himself, as I have witnessed first hand when he paused during a conference I attended in London, which he was chairing, to do a meditation with the audience. However, given what we have learned of channelling through the C's, is it more likely that Farr was channelling STS forces in the same way that Maria Orsic and her fellow female trance mediums of the Vril Society (an offshoot of the Thule Society) had communicated with the so-called 'Aldebarans', who may in turn have been the STS humanoid Antareans from Orion that the C's spoke of: "Antareans were the name given by 4th density groups in contact with the Thule Society on third density Earth, before and during World War One." Incidentally, Rudolf Hess supposedly took part in one of these channelling sessions with Orsic and other members of the Thule Society in 1924.

See: Maria Orsic

An illustration by H. M. Paget showing Florence Farr as Rebecca West in Henrik Ibsen's “Rosmersholm.”

Credit: Public domain.

So influential did Farr’s communications with the Egyptian Adept become that Samuel Macgregor Mathers, the then head of the Golden Dawn, officially recognized this spirit entity as a “Secret Chief,” guiding the organisation’s destiny from the astral planes. An offshoot group known as “The Sphere” was even formed to channel the Egyptian Adept during rituals that were meant to revive the powerful magics of ancient Egypt. Inevitably, some members of the Golden Dawn objected to the growing influence of the Egyptian Adept, seeing her as a threat to the order’s status quo.

News of the growing politics surrounding Florence Farr’s channelling of the Egyptian Adept would unquestionably have reached the ears of Bram Stoker. At the time he was business manager at London’s Lyceum Theatre, the lessee of which was Stoker’s actor friend Sir Henry Irving (who, incidentally, was the role model for the character of Dracula in Stoker’s novel of the same name, published six years before The Jewel of the Seven Stars in 1897). Not only did the theatre become a hive of social activity involving key figures from London’s occult scene, but Florence Farr was herself working at the theatre in charge of the performance, direction and musical composition of plays.

Florence Farr is known to have adhered to the principles of the Victorian New Woman and promoted them in ancient Egypt inspired plays. As such there seems little question that she was one of the main influences behind the character of Margaret Trelawny in Stoker’s The Jewel of the Seven Stars, while Farr’s channelling of the Egyptian Adept most likely helped inspire the idea of Margaret being taken over by a powerful ancient Egyptian queen. This has certainly been the conclusion of occult historian Caroline Tully. She believes that Farr’s contact with the Egyptian Adept was one of the main inspirations behind Stoker’s Queen Tera (Tully, 2018).

Queen Tera/Sobekneferu and the Big ScreenNews of the growing politics surrounding Florence Farr’s channelling of the Egyptian Adept would unquestionably have reached the ears of Bram Stoker. At the time he was business manager at London’s Lyceum Theatre, the lessee of which was Stoker’s actor friend Sir Henry Irving (who, incidentally, was the role model for the character of Dracula in Stoker’s novel of the same name, published six years before The Jewel of the Seven Stars in 1897). Not only did the theatre become a hive of social activity involving key figures from London’s occult scene, but Florence Farr was herself working at the theatre in charge of the performance, direction and musical composition of plays.

Florence Farr is known to have adhered to the principles of the Victorian New Woman and promoted them in ancient Egypt inspired plays. As such there seems little question that she was one of the main influences behind the character of Margaret Trelawny in Stoker’s The Jewel of the Seven Stars, while Farr’s channelling of the Egyptian Adept most likely helped inspire the idea of Margaret being taken over by a powerful ancient Egyptian queen. This has certainly been the conclusion of occult historian Caroline Tully. She believes that Farr’s contact with the Egyptian Adept was one of the main inspirations behind Stoker’s Queen Tera (Tully, 2018).

Across the years there have been various cinematic adaptations of Stoker’s book. They have included 1970’s Curse of the Mummy . This was a made-for-TV film release forming part of British TV’s Mysteries and Imagination anthology series of classic horror and supernatural dramas. Then came 1971’s Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb . This was Hammer Horror’s own unique take on the story. It was not, however, until 1980 and the release of the Orion/EMI film The Awakening, yet another adaptation of Stoker’s The Jewel of the Seven Stars, that Sobekneferu came much closer to being identified with Stoker’s Queen Tera, whose name in the movie was changed to Kara.

Once again, Margaret (played by actress Stephanie Zimbalist) at 18 years old is very gradually taken over by the queen’s spirit, an inevitable consequence of her Egyptologist father Matthew Corbeck (played by Charlton Heston) having found Kara’s tomb 18 years earlier. Margaret’s full transformation into Kara is accomplished inside a London museum as Corbeck tries to resurrect the long-dead Egyptian queen by performing a ritual involving her mummy. He dies in the chaos that ensues. The film’s final scene shows Margaret, now as the queen herself, standing before the tall columned doorway of the museum, a snarl on her now heavily Egyptianized face as she looks out over the strange new world on which she now intends to inflict a reign of chaos and terror.

The crucial thing about The Awakening, which is by far the best adaptation of Stoker’s novel, is the manner it portrays Queen Kara’s back story. She is said to have ruled “3800 years” ago, the exact timeframe of Sobekneferu. Moreover, her name, Kara*, or Ka-Ra, closely resembles Sobekneferu’s coronation name Sobekkara, which means “Sobek is the soul (ka) of Ra (the sun-god).”

*MJF: It is curious that the DC Comics character of 'Kara Zor-El', otherwise known as Supergirl, shares the same name as Queen Kara too.

Once again, Margaret (played by actress Stephanie Zimbalist) at 18 years old is very gradually taken over by the queen’s spirit, an inevitable consequence of her Egyptologist father Matthew Corbeck (played by Charlton Heston) having found Kara’s tomb 18 years earlier. Margaret’s full transformation into Kara is accomplished inside a London museum as Corbeck tries to resurrect the long-dead Egyptian queen by performing a ritual involving her mummy. He dies in the chaos that ensues. The film’s final scene shows Margaret, now as the queen herself, standing before the tall columned doorway of the museum, a snarl on her now heavily Egyptianized face as she looks out over the strange new world on which she now intends to inflict a reign of chaos and terror.

The crucial thing about The Awakening, which is by far the best adaptation of Stoker’s novel, is the manner it portrays Queen Kara’s back story. She is said to have ruled “3800 years” ago, the exact timeframe of Sobekneferu. Moreover, her name, Kara*, or Ka-Ra, closely resembles Sobekneferu’s coronation name Sobekkara, which means “Sobek is the soul (ka) of Ra (the sun-god).”

*MJF: It is curious that the DC Comics character of 'Kara Zor-El', otherwise known as Supergirl, shares the same name as Queen Kara too.

Artist impression of Sobekneferu by London artist Russell M. Hossain. Credit: Russell M. Hossain.

Why exactly the scriptwriter of The Awakening chose a date of 1800 BC for the reign of its Egyptian queen, and how they came to call her Kara is unclear. Whatever the answer, they managed, either consciously or unconsciously, to bring Sobekneferu even closer to the Queen Tera of Bram Stoker’s original novel. In doing so it has helped Sobekneferu to quite literally live again in the modern world. As mentioned at the start of this article, her latest outing was as the Egyptian princess Ahmanet in 2017’s cinematic blockbuster The Mummy. Even here there is a nod to Sobekneferu for Ahmanet is simply a shortened form of Amenemhat, the name of Sobekneferu’s father and half-brother.

Yet can we get closer to the core of this dead queen’s innermost mysteries? Can we find out more about what Sobekneferu was really like as a person? Was she really a sorceress with a profound understanding of ancient magic?

Well, I guess we will have to read Collins' book on Sobekneferu when it comes out in June to find out.

What Collins' article does reveal though is the fascination, bordering on obsession, that late Victorian writers and occultists had with all things Egypt. One can understand this to some extent with the incredible archaeological discoveries that came out of Egypt during the 19th Century and on into the first part of the 20th Century, culminating in the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb by Howard Carter. However, as Laura has pointed out, the occultists mistakenly looked to the Egypt of the Pharaohs for the roots of magic, when in reality they lay with Babylon and Sumeria, whose civilisation was older than that of Egypt, as the C's have confirmed:

Q: (L) Which is the older civilization: Sumerian or Egyptian?Yet can we get closer to the core of this dead queen’s innermost mysteries? Can we find out more about what Sobekneferu was really like as a person? Was she really a sorceress with a profound understanding of ancient magic?

Well, I guess we will have to read Collins' book on Sobekneferu when it comes out in June to find out.

What Collins' article does reveal though is the fascination, bordering on obsession, that late Victorian writers and occultists had with all things Egypt. One can understand this to some extent with the incredible archaeological discoveries that came out of Egypt during the 19th Century and on into the first part of the 20th Century, culminating in the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb by Howard Carter. However, as Laura has pointed out, the occultists mistakenly looked to the Egypt of the Pharaohs for the roots of magic, when in reality they lay with Babylon and Sumeria, whose civilisation was older than that of Egypt, as the C's have confirmed:

A: Sumerian.

Moreover, the Egyptologists mistakenly believed that the Great Pyramid at Giza and the Sphinx were built by the Pharaohs (they still do) when in fact we know they were built by a post-Atlantean civilisation that had little or no connection with the later nomadic people who would become the Egyptians.

I would like to highlight though Queen Sobekneferu's focus on the seven stars of Ursa Major (the Great Bear, otherwise known as the "Big Dipper or "the Plough"). We know from the myth of Hamlet's Mill as diascussed by Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend in their book of the same name that the ancients in Megalithic times saw in the stars the key to the precession of the equinox. Quoting from Wikipedia:

The main argument of the book may be summarized as the claim of an early (Neolithic) discovery of the precession of the equinoxes (usually attributed to Hipparchus, 2nd century BCE), and an associated very long-lived Megalithic civilization of "unsuspected sophistication" that was particularly preoccupied with astronomical observation. The knowledge of this civilization about precession, and the associated astrological ages, would have been encoded in mythology, typically in the form of a story relating to a millstone and a young protagonist—the "Hamlet's Mill" of the book's title, a reference to the kenning Amlóða kvern recorded in the Old Icelandic Skáldskaparmál. The authors indeed claim that mythology is primarily to be interpreted as in terms of archaeoastronomy ("mythological language has exclusive reference to celestial phenomena"), and they mock alternative interpretations in terms of fertility or agriculture.I would like to highlight though Queen Sobekneferu's focus on the seven stars of Ursa Major (the Great Bear, otherwise known as the "Big Dipper or "the Plough"). We know from the myth of Hamlet's Mill as diascussed by Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend in their book of the same name that the ancients in Megalithic times saw in the stars the key to the precession of the equinox. Quoting from Wikipedia:

The book's project is an examination of the "relics, fragments and allusions that have survived the steep attrition of the ages". In particular, the book reconstructs a myth of a heavenly mill which rotates around the celestial pole and grinds out the world's salt and soil, and is associated with the maelstrom. The millstone falling off its frame represents the passing of one age's pole star (symbolized by a ruler or king of some sort), and its restoration and the overthrow of the old king of authority and the empowering of the new one the establishment of a new order of the age (a new star moving into the position of pole star).

Two of Ursa Major's stars, Dubhe and Merak, can be used as the navigational pointer towards the place of the current northern pole star, Polaris in Ursa Minor. Ursa Major, along with asterisms that incorporate or comprise it, has been, and continues to be, significant to numerous world cultures, often being viewed as a symbol of the north. The constellation has been seen as a bear, usually female, by many civilizations. This may stem from a common oral tradition of Cosmic Hunt myths stretching back more than 13,000 years. Curiously, Ursa Major is one of the few star groups mentioned in the Bible (See Job 9:9; 38:32; – Orion and the Pleiades being others), Ursa Major was also pictured as a bear by the Jewish peoples. "The Bear" was translated as "Arcturus" in the Vulgate and it persisted in the King James version of the Bible.

In Theosophy (which is based primarily on Madam Blavatsky's writings), it is believed that the Seven Stars of the Pleiades focus the spiritual energy of the seven rays from the Galactic Logos to the Seven Stars of the Great Bear, then to Sirius, then to the Sun, then to the god of Earth (Sanat Kumara), and finally through the seven Masters of the Seven Rays (i.e., Blavatsky's Ascended Masters) to the human race.

It may well be that the Golden Dawn shared a similar outlook to their Theosophist contemporaries where the Seven Stars of the Great Bear were concerned, one which may have informed Stoker in his writings.

But could there be another connection with Ursa Major, one that relates directly to the quest for the Grail?

Session 26 July 1997:

Q: What is the meaning of 'The Widow's Son?' The implication? In Theosophy (which is based primarily on Madam Blavatsky's writings), it is believed that the Seven Stars of the Pleiades focus the spiritual energy of the seven rays from the Galactic Logos to the Seven Stars of the Great Bear, then to Sirius, then to the Sun, then to the god of Earth (Sanat Kumara), and finally through the seven Masters of the Seven Rays (i.e., Blavatsky's Ascended Masters) to the human race.

It may well be that the Golden Dawn shared a similar outlook to their Theosophist contemporaries where the Seven Stars of the Great Bear were concerned, one which may have informed Stoker in his writings.

But could there be another connection with Ursa Major, one that relates directly to the quest for the Grail?

Session 26 July 1997:

A: Stalks path of wisdom incarnate.

Q: Why is this described as a Widow's son? This was the appellation of Perceval...

A: Perceval was knighted in the court of seven.

Q: The court of seven what?

A: Swords points signify crystal transmitter of truth beholden.

The C's subsequently elaborated further on this point in connection with Laura's questions concerning the Egyptian Pyramid Texts and the Seven Sages (Could these be the Master of the Seven Rays and Blavatsky's Ascended Masters? See also see my previous post.) in the Session dated 22 August 1998:

Q: (L) The Pyramid Texts also talk about the ‘Duat.’ What is this?

A: Scene of martyrdom.

Q: (L) They also talk about the ‘Seven Sages.’ You once said that Perceval was ‘knighted in the Court of Seven and that the sword’s points signify ‘crystal transmitter of truth beholden.’ Do these seven sages relate to this ‘Court of Seven’ that you mentioned?

A: Close.

Q: (L) When you said ‘swords points signify crystal transmitter of truth beholden,’ could you elaborate on that remark?

A: Has celestial meaning.

Curiously, the issue of the precession of the equinox came up earlier in that same session in relation to a supernovae in Orion:

Q: ..... Now, according to this book, the ‘Message of the Sphinx,’ they are saying that the orientation of the pyramid complex which includes the Sphinx, designates or denotes a time, or replicates on the ground the pattern of Orion related to the constellation of Leo exactly 10,500 years ago. What is the significance of this date 10,500 years ago?

A: Complex, but what about Orion?!?

Q: What about Orion?

A: For you to surmise.

Q: Was this a date when the ships from Orion arrived to go into orbit around the Earth?

A: No. Now you should study all you can about supernovae.

Q: Okay, there was a mention of a supernovae in this book. Was there a supernova at that particular time?

A: Maybe, but the real question should be: Will there be one again, and soon?

Q: They have said that this designates the lowest point of Orion in the precessional cycle, the nadir of the cycle, and that the midheaven would be 2400 AD. If you have the representation of this precessional nadir, what is the next ‘notch’ on the clock? Is it going to be the midheaven of the cycle 400 years or so from now?

A: Best not to assume without adequate date.

Of course, if the Earth was knocked off its present axis by a comet, or the axis changed because of a straightening up of the Earth's tilt, as seems to be the case at the present time, then the stars used to note precession in relation to fixed points on the Earth like Giza (the ancient world's zero meridian) and Stonehenge would change position in the night sky too.

However, it is the C's reference to 'the court of seven' and 'swords' points signify a crystal transmitter of truth beholden’ having a celestial meaning that intrigues me here. Moreover, when Laura asked whether the Seven Sages related to the court of seven, the C's did not say no but said "close" instead, which normally means that although the suggestion was not correct, there may still be some connection between the two things. But what of the celestial meaning?

The word "celestial" when used as an adjective means "positioned in or relating to the sky, or outer space as observed in astronomy", as in a celestial body. It can also mean in a religious context "belonging or relating to heaven", as in the celestial city. Finally, it can mean something which is "supremely good" as in celestial beauty. However, sticking with the first meaning, could the C's have meant that the court of seven related to a celestial body or group of such bodies, as in a star or constellation? If so, could they have had in mind Ursa Major whose stars may have been be viewed by the ancients as a handle turning the heavens around the pole star Polaris?

However, it is the C's reference to 'the court of seven' and 'swords' points signify a crystal transmitter of truth beholden’ having a celestial meaning that intrigues me here. Moreover, when Laura asked whether the Seven Sages related to the court of seven, the C's did not say no but said "close" instead, which normally means that although the suggestion was not correct, there may still be some connection between the two things. But what of the celestial meaning?

The word "celestial" when used as an adjective means "positioned in or relating to the sky, or outer space as observed in astronomy", as in a celestial body. It can also mean in a religious context "belonging or relating to heaven", as in the celestial city. Finally, it can mean something which is "supremely good" as in celestial beauty. However, sticking with the first meaning, could the C's have meant that the court of seven related to a celestial body or group of such bodies, as in a star or constellation? If so, could they have had in mind Ursa Major whose stars may have been be viewed by the ancients as a handle turning the heavens around the pole star Polaris?

Yeah, yeah. The 'bad guy' always has to be a German.

Let's see...

- Herr Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (1874 – 1965), Nepalese lover of spirits and founder of finger acrobatics in England.

I have to admit that I thought it odd that the article on the Golden Dawn should imply that Crowley was a "German" occult writer when, in fact, he was very much British. In fairness, the villain in many mainstream US movies in recent times has often been British rather than German. It could just be that RADA trained British actors are better suited to playing villains and the clipped accent probably also helps. If you ask any actor, they will tell you it is much better playing the villain than the hero since you can really get your teeth into the part of the baddy. However, I would assume the article is correct in proposing that Crowley had a major influence on the neo-pagan movement in Germany.

I assume you by this you mean Churchill's famous 'V' for victory sign?As a side note.

What Uncle Edward Alexander teached little Winston Leonard, was to counter the 'phallic' salute of Herr Hiller with the 'vaginal' sign of Thyphon.

View attachment 72279

However, he sometimes reversed the sign like so:

Although the apocryphal explanation is that this was the 'V' sign the English archers showed the French army at the Battle of Agincourt because the French would cut off the bow string fingers of captured English archers, the sign in today's parlance normally equates with the expletive delitive expression "f**k off", as denoted by the middle finger gesture in America. Churchill was renowned for his crudity so you can take your pick here.

I think that is wrong. What 'major influence' would he have on the Ariosophists and the Völkische Bewegung? He was sitting together with the old O.T.O and the Pansophic guys. Grosche with his Fraternitas Saturni was the only one, who seems to have had some interest in what Crowley had to say. But Fraternitas Saturni was practically unknown till the start of the 1970s.However, I would assume the article is correct in proposing that Crowley had a major influence on the neo-pagan movement in Germany.

That with Churchill..., I think, I read this somewhere in one of Kenneth Grant's books.

The sequels to the Hitler story by Miles Mathis. Now Churchill also appears on the stage:

More WW2 Fakes

The Battle of France

More WW2 Fakes

The Battle of France

Attachments

...Once again, ... 18 years old ... found tomb 18 years earlier ...Why exactly the scriptwriter of The Awakening chose a date of 1800 BC ... is unclear.

It's because the egyptian mummy queen will live again. That's the whole plot of the story, isn't it.

18 = 6+6+6 = 6_6_6

Chai (Hebrew: חַי "living" ḥay) ... The word is made up of two letters of the Hebrew alphabet – Chet (ח) and Yod (י), forming the word "chai", meaning "alive", or "living". The most common spelling in Latin script is "Chai", but the word is occasionally also spelled "Hai".

There have been various mystical numerological speculations about the fact that, according to the system of gematria, the letters of chai add up to 18.

-> Chai (symbol) - Wikipedia

German "Heil" : expresses pardon, success, wholeness, health and in religious meaning especially salvation.

"Heil Hitler!"

Adolf Hitler = 18

Last edited:

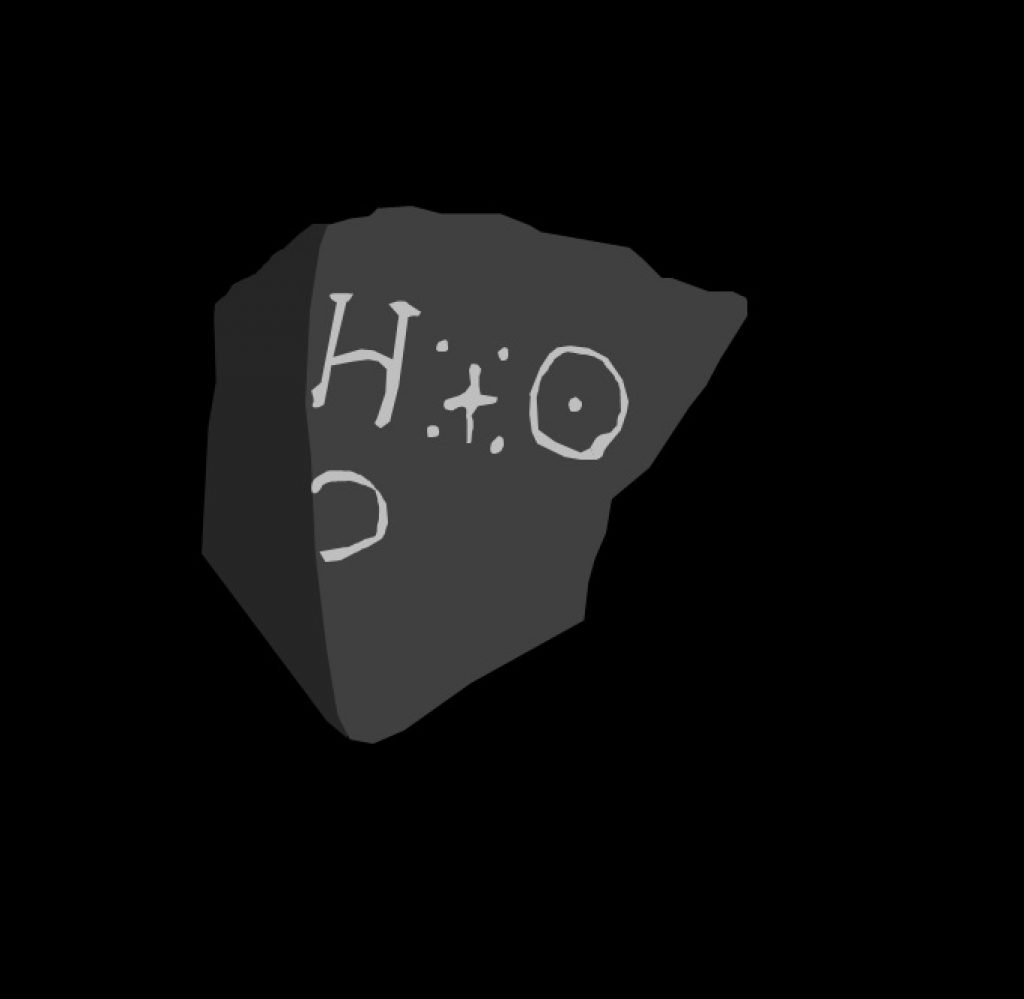

In my post providing an update on Oak Island I referred to a Templar marker stone device, which members of the Oak Island research Team linked with a similar device that had been seen on the so-called "H/O Stone" discovered on Oak Island in 1921. See extract below:

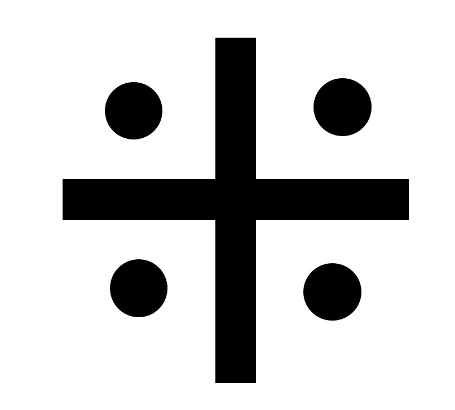

They were next shown another cross symbol, which the Templars used as marker stone device consisting of a straight cross surrounded by four dots, which looked something like this but with a smaller central cross:

This immediately reminded them of the cross device on what is known as the "H/O stone", a fragment of stone discovered on Joudrey’s Cove on Oak Island in 1921 after the boulder it was part of was blown up by treasure hunters thinking the treasure lay buried under it. .

Note again the alchemical symbol of the circle with the dot in the middle of it adjacent to the cross. In episode 2 of season 4 of the show, the late Zena Halpern had shown one of Rick Lagina and Doug Crowell an image of a Crusader coin bearing a symbol consisting of a cross with a dot in each quadrant, a variation of what is known as the ‘Crusader cross’. She observes that this Crusader cross is strongly reminiscent of one of the three symbols carved into what many Oak Island enthusiasts refer to as the H/O stone.

I was sure I had seen something like it before. Sure enough, whilst watching an old episode of Ancient Aliens, I suddenly remembered. A cross with four dots within it, as shown above, also appears in the Buddhist swastika or symbol for peace (see below):

I was sure I had seen something like it before. Sure enough, whilst watching an old episode of Ancient Aliens, I suddenly remembered. A cross with four dots within it, as shown above, also appears in the Buddhist swastika or symbol for peace (see below):

Quoting from the Tibetan Buddhist Encyclopedia: (see:The Swastika Symbol in Buddhism - Tibetan Buddhist Encyclopedia}

The swastika (Sanskrit svastika, "all is well") is a cross with four arms of equal length, with the ends of each arm bent at a right angle. Sometimes dots are added between each arm.

The swastika is an ancient symbol found worldwide, but it is especially common in India. It can be seen in the art of the Egyptians, Romans, Greeks, Celts, Native Americans, and Persians as well Hindus, Jains and Buddhists.

The swastika's Indian name comes the Sanskrit word svasti, meaning good fortune, luck and well being.

In Hinduism, the right-hand (clockwise) swastika is a symbol of the sun and the god Vishnu, while the left-hand (counterclockwise) swastika represents Kali and magic. The Buddhist swastika is almost always clockwise, while the swastika adopted by the Nazis (many of whom had occult interests) is counter-clockwise.

In Buddhism, the swastika signifies auspiciousness and good fortune as well as the Buddha's footprints and the Buddha's heart. The swastika is said to contain the whole mind of the Buddha and can often be found imprinted on the chest, feet or palms of Buddha images. It is also the first of the 65 auspicious symbols on the footprints of the Buddha.

However, as the extract from the Encyclopedia mentions, the swastika is an ancient symbol that was used by many ancient cultures. This suggests it may have been a symbol inherited from a precursor civilisation such as Atlantis. We know that the Nazis inherited it from the Thule Society (with its potential Illuminati/Rosicrucian connections and the Thule Society's interest in Vril or free energy). If we strip away the religious meaning and focus on science, we may be looking at an ancient symbol conveying the torsion forces which result from high spin states.

I recall that in one of Joseph Farrell's books he showed how the swastika could represent field rotation. Unfortunately, I can't track the appropriate book down at the moment but he does talk about his ideas in an interview he gave to Project Camelot a few years ago from which I set out below an extract (JF being Joseph Farrell):

BR: And his words were that his jaw dropped. He never knew such a thing existed. It’s really interesting to us that you’ve been down that same rabbit-hole. And what I’d love to ask you about - if this doesn’t deviate from your thought-line here - is: What is the connection between this hard, but brilliant and out-of-the-box physics, with the occult?I recall that in one of Joseph Farrell's books he showed how the swastika could represent field rotation. Unfortunately, I can't track the appropriate book down at the moment but he does talk about his ideas in an interview he gave to Project Camelot a few years ago from which I set out below an extract (JF being Joseph Farrell):

JF: I think... Again, if you go back to the remarks I began with, I think if you go far enough back and look at certain types of texts, for example, the Hermetica, okay? And read them without the standard academic approach with metaphysics eyeglasses on, and read them rather as a topologist - as a mathematician - would read these texts, or as even a materials engineer, you know, might read these texts, what pops out of these things is a profound metaphor of a physical medium that creates information, and that’s a very modern idea.

In fact, it’s so modern, you know, it starts popping up in the Soviet Union in the 1970s and begins to kind of spread from there. All of this stuff is popping out of the Soviet Union.

So in other words, way back when - if we go back to the Hermetica - here we’re dealing with a text approximately, oh give or take, you know, 2,000 years old, so in others words... But it’s an Egyptian text even though it’s written in Greek. Its provenance is clearly Egyptian, okay? So this is very old and yet it contains this profoundly sophisticated physics metaphor.

That’s what really popped out at me, you know, when I was reading these texts. It wasn’t that I was supposed to be looking and seeing Platonic Universals, you know, the chair-of-all-chairs and the horse-of-all-horses. No. None of that was what was popping out at me. What Plato’s talking about is topology. He’s talking about common surfaces with common forms, okay? So I’m looking at this, and then I’m looking at the Nazis, and they’re coming up with these theories essentially in the ’20s and ’30s that are looking at the physical medium as an engineer-able reality. In other words, in a certain sense, as an information-creating medium. So... And again, the key to creating stable information is rotation, okay? Torsion, and so on and so forth.

So I’m thinking: Well, this appears to be precisely what we see going on with this Bell project. They are somehow pursuing this idea of physics. And one of the things that leapt out at me that kind of made this connection very clear is...

In my book, The Philosopher’s Stone, I refer to a fellow by the name of “Himmler’s Rasputin” - if you can imagine [laughs] Heinrich Himmler having a personal Rasputin! Well this guy’s name is Karl Maria Wiligut. Okay? He has a number of aliases that he wrote esoteric treatises under. But his basic conception is that the whole universe arises out of a tension between two counter-rotating spirals which create the “World Egg”. Okay?