Dear lord, that perpendicularity restoration thing is one of the craziest predictions or prophecies of the C's. Here's the main session about it:

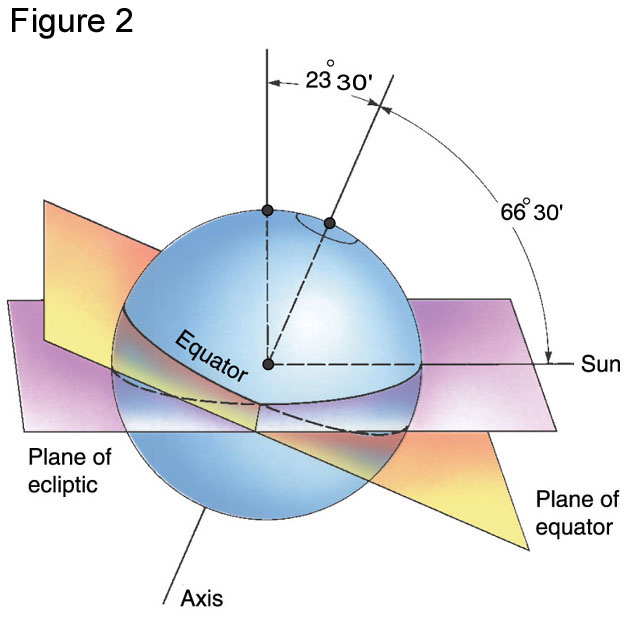

So what does it mean? Currently the earth is tilted like this:

A return to perpendicularity refers to earth's axis of rotation shifting in such a way that the equator would become level with the plane of the ecliptic - so no more 23.30 degree tilt. That means no more seasons of spring, summer, fall and winter!

In a recent session, the Q about perpendicularity was asked again:

As for where the North Poles will actually stabilize, it's hard to say. I think it depends on when and where the comets hit.

One result might mean that the area around Hudson Bay in Canada becomes the North Pole again. I say again because prior to the Younger Dryas impact, one theory is that the Hudson Bay was basically the North Pole. It was the impact of a giant dustball comet on the ice sheet over the Bay hit, causing the last destruction of Atlantis, and changing the axial rotation of the Earth to it's current degree of tilt.

Belo I've posted a narrative as written in the horrifying book

The Cycle of Cosmic Catastrophes. The story is not entirely correct, as the authors had no knowledge of a high-tech Atlantean civilization. But I think it is good to post in that this 'return to perpendicularity' topic is no small thing. If we take the C's at their word, a comet big enough to move the entire planet might be required, and there are many, many potential effects that come along with comets. An Ice Age is one of the main likely potential effects of comets, and also the magnetic field going haywire.

I don't know how else perpendicularity could be restored, unless it's way more gentle, and has to do with the Sun's Twin and gravity effects or something, in which case I'm way outta my league. But the C's seemed pretty clear - cometary bodies will restore perpendicularity. It's kind of hard to comprehend. So non-anticipation is the name of the game, still. And doing what is in front of us to do, having faith that the universe knows what it's doing.

I really recommend reading the whole book and looking through all the evidence. It's fascinating and easy to read, science made for the general public. The book itself also includes portions of Indigenous legend, myth, and prophecy, many of which stem from this point in time where the destruction was unimaginable and the culture of the earth was forever changed. So it kinda fits in with the theme of the thread, too.

The dazzling flash of the nearest explosion temporarily blinded some of the tribe. Others closed their eyes tight, but even then, the fierce light stung their eyes. Some held their hands up as shields, but the intense light illuminated their flesh with an orange glow, eerily outlining the bones in their hands. Most of them curled up and buried their heads to shut out the painful brilliance, but their skin began to blister from the intense glare and heat. Hastily, they pulled cloaks and blankets over their heads, mumbling frantic prayers to the angry gods.

When the ground shock waves from the impacts arrived, the earth shook violently for a full ten minutes in great rolling waves and shudders. Rocks broke loose, clattering down from the outside cliff face, and fell from the roof over their heads. Screaming in pain, some people were injured by the falling rocks. Nearby trees shook and swayed violently before toppling over. Short, narrow fissures opened and snaked across the rocky field in front of them. The stream beyond the caves cascaded into the newly opened cracks and disappeared. Choking clouds of dust rose to obscure the view, as the People huddled in their shelter, certain that they were going to die.

The Blast Wave and the Bubble

Within seconds after the impact, the blast of superheated air expanded outward at more than 1,000 miles per hour, racing across the landscape, tearing trees from the ground and tossing them into the air, ripping rocks from mountainsides, and flash-scorching plants, animals, and the earth. Nearly the only living things to survive close to the blast had hidden underground, underwater, behind hills, or inside some other type of shelter. Millions of unlucky animals were out in the open.

By the time the blast wave passed over the Clovis tribe, it had slowed, but it still was traveling four times faster than tornado winds. It shook the ground just as the earthquakes had done. Fiery hot, windborne sand and gravel pelted the walls of their hiding place and ricocheted around them like bullets. Within moments, the flying debris cascaded off the outside cliff face and piled up around the opening of the shelter to the height of a man, almost closing the entrance and sealing them in. That probably saved their lives.

Across upper parts of North America and Europe, the immense energy from the multiple impacts blew a series of ever-widening giant overlapping bubbles that pushed aside the atmosphere to create a near vacuum inside. After the outer edge of the closest bubble passed over the Clovis band, the wind speed dropped, and air pressure fell precipitously, making it difficult for the survivors to breathe the thin air. In the back of their cave, the People gasped for breath as their bodies became starved for oxygen. Each labored breath of the superhot dusty air seared their lungs.

Behind the expanding edge of the bubble, Earth was stripped of the protective shield of the atmosphere and was at the mercy of a different barrage. The enormous blast ejected tiny, fast-moving grains in all directions through the thin air. Some went sideways to lodge in trees, plants, and animals; others went up and came back down. With almost no atmosphere to slow them, they fell faster and faster, hitting Earth at hundreds of miles per hour. At the same instant, large atoms blown out of the turbulent sun and high-speed galactic cosmic rays streamed unhindered through the empty bubbles. Traveling at several percent of the speed of light, the radiation bombarded the planet like microscopic bullets, speeding deep into exposed flesh and bone.

In their headlong retreat toward shelter, some of the tribe had dropped their spears. As they stared out in disbelief, the invisible particle bombardment made their abandoned spears twitch and vibrate on the ground. Millions of high-speed microscopic grains peppered the exposed flint surfaces and blew tiny holes in the wood. At the same time, tiny speeding pellets ripped unseen through trees and plants, shredding and stripping off leaves and twigs, which danced around eerily on the ground, as if demons were trying to pick them up.

The particle onslaught struck mammoths and larger animals that could not find shelter, lodging in their tusks or horns and sinking deep into their eyes and flesh. Some animals stampeded in terror, while others dropped where they stood, unaware of the invisible particles that had hit them. Before long, the outward push of the shock wave slowed and stopped, and then the vacuum began to draw the air backward.

As the expanded atmosphere rushed back toward the impact site, the bubbles collapsed, sucking white-hot gases and dust inward at tornado speeds and then channeling them up and away from the ground. Climbing high above the atmosphere, some of the rising debris escaped Earth's gravity to shoot far out into space like a dusty geyser, while the rest flowed out as a reddish brown mushroom cloud that flattened out for thousands of miles across the upper atmosphere. As the expanding cloud blocked the sun, darkness engulfed the areas near the impacts.

Some of the dust and debris lifted by the powerful updraft was too heavy for the atmosphere and began drifting and crashing back to earth. Still superhot from the blast, it gave off a powerful lavalike glow, reheating the still smoldering ground and air as it fell. In places, temperatures, which had fallen after the fireball passed, quickly rose dozens of degrees again.

Landing on top of the continental ice sheet, the hot particles melted holes and pits into the top of the ice. Suddenly liberated, meltwater coursed off the ice sheet in all directions. The raging updraft through the hollow bubbles created an equally powerful downdraft of frigid high-altitude air, traveling at hundreds of miles per hour. With temperatures exceeding 150 degrees F below zero, the downward stream of air hit the ground and radiated out from the blast site in all directions, flash-freezing within seconds everything it touched. Some of the animals that had survived the initial fiery shock wave froze where they stood, while others survived for only a few minutes more. The howling, frigid blast turned trees and plants into brittle ice statues. The rapid temperature fluctuations meant the end for millions of plant and animals—and it was not over yet.

The Earth Shakes and Burns

The impacts and shock waves triggered enormous earthquakes along various fault lines from the Carolinas to California and shook some dormant volcanoes awake in Iceland and along the Pacific coast. Erupting with furious activity, they spewed hot lava across the landscape, releasing dust, sulfur, and noxious chemicals into the atmosphere and adding to the already heavy cloud cover.

The impacts, the blast wave, and the eruptions started thousands of ground fires wherever there was enough fuel to feed the flames. In some cases, the fires went out quickly, as the high-speed winds and oxygen-poor air snuffed them out. Other parts of the landscape, tinder dry from the winter freeze, burned with fierce intensity for days following the impact.

Fast-moving, wind-driven wildfires formed spiraling tongues of raging flames that twisted for thousands of feet into the air, and the wild inferno raced through the forests faster than birds and animals could flee. The roar of the fires shook the ground, and the fierce heat blew apart trees like bombs, exploded rocks like shrapnel grenades, and set off steam explosions whenever the fast-moving fire front jumped across frozen ponds and streams. When the fires had finally burned themselves out, there was little left besides smoldering stumps and telltale charcoal strewn across the continents.

The cold climate supported more sparse grass than trees, and the extensive Ice Age grasslands burned intensely and quickly. Afterward, the ash from the grass fires washed away in the steady rains, leaving little evidence behind. As those grasslands went up in smoke, the main food supply of millions of mammoths, horses, camels, and bison disappeared within minutes to hours, leaving hundreds of thousands of square miles stripped of plant food and covered with black charcoal and white ash. For many parts of the north, as far as the eye could see, the ground was either burning or already black and charred.

The eruptions and continental fires lifted additional tons of ash and soot into the atmosphere, further darkening the sky. Along with that dust, millions of tons of dangerous cometary chemicals drifted high up into the sky, only to float back to earth later. In some places, the air was too toxic and oxygen-depleted to support life.

Earth's Magnetic Field Flickers

Shocked by the thunderous impacts, Earth's magnetic field flickered briefly, causing the magnetic poles to wander crazily across the planet. The north magnetic pole briefly approached the equator before it recovered. As the field wavered and weakened, Earth became even more exposed to incoming cosmic rays.

With the magnetic field oscillating, animals that navigated by the field became lost and confused. Unable to find their way, tens of thousands of turtles, whales, and porpoises beached on shorelines and became stranded. Millions of birds, trying to flee the explosions, used the wavering field to navigate in the wrong direction and perished.

The bombardment of the sun continued to create massive explosions that blasted solar material toward the Earth and the moon in seemingly endless waves. With less protection from our magnetic field, life on Earth was pummeled by nearly continuous deadly solar radiation.

The Carolina Bays

In the split second that the bottom half of the giant dustball-comet crashed into the ice of Hudson Bay, it vaporized on impact and exploded upward violently, shattering the upper portion of the impactor and spewing pieces of the comet across the continent. At the same instant, the impact blew apart nearly 200,000 cubic miles of the glacier, sending the icy debris hurtling through the air or skipping across the landscape. Arcing swiftly away from the multiple impact sites, a rain of incandescent debris and chunks of steaming ice showered down across most of North America, Europe, and Asia.

People and animals many hundreds of miles away from the north saw the bright flare of the massive explosions and felt the ground shake. Those that looked up saw the incoming sizzling clouds of debris hurtling toward them through the daytime sky in total silence. The dangerous chunks traveled far faster than the speed of sound, so no one heard them coming.

Within minutes, the massive low-flying lumps crashed into the Carolinas and the eastern seaboard, exploding into fireballs and gouging out the Carolina Bays. In some areas along the coast, the thickest ice bombs leveled nearly all the landscape for hundreds of miles and torched entire forests. Other giant flying lumps exploded to form shallow craters across wide stretches of Nebraska, Kansas, Texas, Oklahoma, Arizona, and New Mexico. Within thirty minutes of impact, some ice had fallen as far away as California and Mexico, more than 2,000 miles away.

Pieces of flying ice and debris both large and small fell on nearly every section of the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean. A similar barrage blanketed large parts of Europe and Asia, and some pieces reached as far as Africa and the rain forests of South America, although Australia was spared. More than one quarter of the planet was under siege.

The dustball-comets were high in carbon, and so was the burning vegetation. The massive explosions melted the carbon and lifted it high into the atmosphere or carried it in the flying chunks landing across the Northern Hemisphere. As it came back down, it littered the landscape with millions of tons of small chunks of black glass, carbon spherules, and fine carbon dust. Trapped within the glass were minute particles of star-stuff, with chemistry unlike anything on this Earth.

Surging Ice

As the largest dustball-comet collided with the North American glacier in Hudson Bay and blew a hole completely through the ice sheet, it sent high velocity meltwater surging under the ice. At the same instant, it cracked the ice and sent it skidding out through Hudson Strait, releasing hundreds of thousands of fractured ice chunks into the North Atlantic as icebergs.

Caught by the powerful ocean currents, some of them eventually drifted as far away as Europe, Africa, and Florida. Along the southern edge of the ice sheet in North America, fires were the greatest danger, but the ice was a serious problem by itself. The meltwater surges lifted and floated large sections of the ice, causing monolithic ice blocks to slide southward along hundreds of miles of the ice front. Moving nearly as fast as a horse can run, the blocks plowed over the forests, shearing trees off at stump level and burying meadows that were close to the ice sheet.

The surging meltwater sluiced through the soft sediment under the glaciers, carving hundreds of thousands of spindle-shaped drumlins across three continents. Jolting ahead like a relentless bulldozer, the ice pushed up huge piles of glacial rock and gravel moraines, until the meltwater finally subsided and the wild ice ride was over.

Slides and Tsunamis

Sailing through the air, thousands of ice chunks and clouds of slushy water splashed down into the Atlantic, exploding with colossal detonations. The multiple concussions triggered immense underwater landslides along the continental shelf of North Carolina and Virginia, releasing thousands of cubic miles of mud. In turn, that unleashed 1,000-foot-high tidal waves that raced away from the coast at 500 miles an hour. Aimed out to sea, the waves had little effect on the North American coast, but they were headed straight for Europe and Africa.

Things were quiet in Europe and North Africa for a while after the last of the impacts, but the damage was extensive, and no part of the continents was spared. Tens of millions of animals lost their lives all across those con tinents, and large areas of vegetation were flattened or still burning. Europe seemed safe in the aftermath.

Some people had survived the impacts in Europe, and nine hours later, a few survivors in Ireland came out of hiding to forage for food along on the seacoast. The only warning of trouble came just minutes in advance, when the tide withdrew at an alarming rate, suddenly exposing hundreds to thousands of feet of offshore mudflats. Startled and fearful, the people turned and ran, but it was too late.

Nearly 100 feet high and moving at 400 miles per hour, 1,000-mile long megawaves suddenly rose up from the ocean to surge across the shorelines of Europe and Africa. Rushing hundreds of miles inland beyond the coasts, they devastated everything in their path and obliterated all remaining human coastal settlements. Nearly everyone living along the shores of western Europe and North Africa perished instantly.

With its momentum spent, the churning water paused briefly and began its rush backward to the coast. As it did, the swirling muddy water carried with it rocks, smashed trees, and the battered remains of plants and animals, pulling them all back into the Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

During this surge, the immense force of the crashing waves triggered offshore African slides, sending a second round of megawaves racing back toward North and South America. The people in the Americas suffered little damage from the initial tsunamis, but they were not so lucky with the ones returning from Europe. This time, the monstrous waves caught unsuspecting survivors on the Atlantic coastlines of both continents. Hundreds of people disappeared under the churning 100-foot waves that rolled miles inland across what had once been fertile lowlands.

This second round of giant waves triggered the largest slides off the mouth of the Amazon River in South America. A third round of mountainous tsunamis raced back off to smash into North America, Africa, and Europe once more. This time, it mattered little—no one was left on the coasts to see the waves coming. For more than a day, the reflecting waves ricocheted back and forth across the Atlantic, growing smaller with each transit. Finally, with their energy spent, the deadly waves faded away.

If there had been anyone still alive along any coastline around the Atlantic, they would have seen a startling sight in some places: burning water. The churning waves and underwater slides exposed giant deposits of frozen methane off North America and Europe, and after the pressure was removed, the methane flashed into gas and bubbled energetically to the

surface. The firestorm and falling hot rocks and particles ignited some of the rising gas plumes, so that here and there miles-long tongues of orange blue flames flickered and danced across the sea surface. For weeks, the sea burned or boiled with escaping methane.

Rain and Snow

Within minutes after the impacts, the subzero air and the rising water vapor combined to produce heavy snow and sleet as the supersaturated atmosphere dropped its burden, causing snow to fall as far away as Mexico, the Caribbean, and North Africa. Gradually, in the south, the snow turned to rain, which continued day after day, stretching into weeks, and then into months. It did not fall heavily, as in thunderstorms, but steadily as a slow drizzle. Rivers and streams swelled beyond flood stage and remained there for months.

You might think that the rain was good—a cleansing rain to put out the fires and wash the land clean, but there was a dark side. Millions of tons of noxious chemicals fell with the rain. Combining with hydrogen, they formed a toxic brew of acid rain—hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric, and carbonic acids. In places, they etched the rocks, ate holes through leaves, and burned the flesh of living animals.

Even though the surviving people found shelter from the blistering rain, they still had to drink. But the water was laced with acid and traces of arsenic, formaldehyde, cyanide, and toxic metals—not enough to kill the strongest ones, but enough to make them ill.

Meltwater Flooding

All the combined heat turned millions of tons of ice into water and sent it coursing off the continental glaciers to pool in the existing glacial lakes. As the lakes quickly filled and overflowed, their ice dams failed, sending monstrous floods roaring on to the next lake. As each flood poured into the lake below it, that lake's dam failed in turn, creating a cascade of ever-growing floodwaters raging toward the Mississippi, into the St. Lawrence, and out through all other outlets into the oceans. In what is now Washington state, a dam broke in a huge glacial lake, sending floodwaters more than 800 feet deep cascading to the Pacific through narrow clefts in the mountains, sweeping away topsoil, trees, plants, people, and animals, and etching giant grooves into the solid rock walls.

From every existing river and stream, frigid freshwater flooded into the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic Oceans. The sudden pulse of melted ice caused sea levels to rise many feet within a few weeks, inundating the lowlands around the world. Relentlessly, day by day, thousands and then million of square miles of once verdant grasslands and forests slipped beneath the rising ocean waves, never to be seen again.

The Gulf Stream and the Climate

When the underwater slides began, thousands of cubic miles of mud, sand, and gravel slid right across the path of the Gulf Stream and the other deep ocean currents that make up what is called the "ocean conveyor" in the Atlantic. The immense force of the slides rerouted the conveyor sideways, disrupting its flow.

Simultaneously, near-freezing freshwater from the floods acted like a lid on the North Atlantic, slowing down the conveyor and then stopping it completely. With the North Atlantic deprived of warm water, within days temperatures began to fall around the North Atlantic from the northeastern United States to Canada and on to Europe. The stalled conveyor, coupled with sunlight-blocking dust and clouds, was too much for the climate to overcome. Within days or weeks after the impacts, continental temperatures rapidly fell to well below freezing, and a brutal Ice Age chill once again spread across the land. Temperatures remained low for more than 1,000 years during a time called the Younger Dryas.

Algal Blooms and the Black Mat

By the time the waves grew quiet and the raging winds subsided, additional tens of millions of animals had perished, including most of the people living in the Northern Hemisphere. Slowly, the survivors struggled to return to a normal existence. Within months, the landscape began to stabilize, but it still looked like a barren, blackened moonscape in many areas. The impacts, firestorms, and tidal waves had devastated large tracts of the most fertile land along the oceans and river tributaries.

Even though the worst had passed, the trouble was not over. It was still too dark and cold for most plants to grow well. The surviving animals had little to eat, and starvation overcame many of them during the next few months. A few plants did very well during the troubled times, however. Known as "disaster species," some of them were the most primitive plants, which could live well under difficult conditions that hampered other forms of life.

One such species was freshwater algae, which underwent explosive growth. With almost no remaining predators to keep them in check, the algae feasted on the rich mix of chemicals in the environment, some of which are fertilizer for algae. As other plants and animals decayed, they freed iron, nitrogen, sulfur, and other nutrients that spurred on the algae to ever-more-frenzied growth. Dense blue-green mats of algae choked the ponds, streams, and rivers, and as the algae died, they drifted down to clog the bottoms. All over the continents, thick black mats formed. Their explosive growth sometimes filled the lakes and ponds with deadly nerve toxins, which unsuspecting thirsty animals drank in large quantities. Within hours, many animals died alongside the seemingly life-giving waters.

For nearly 1,000 years, algae controlled the lakes and waterways, until their abundant food supply eventually dwindled and their predators returned. Finally, balance was restored, and the algal blooms ceased.

A New Beginning

In spite of all that had happened, most of the Clovis tribe survived in their rock overhang. Across the continent, most people were gone, but a few other small bands made it through. There was no pattern to the survival— the tragedy skipped over some people to strike those standing next to them. The survivors could only believe that the hand of the Creator had spared them that day, but they still faced a devastated world.

In Australia, Africa, and South America, far away from the northern blasts, most people made it through, even though the Event altered the global climate. Over the course of the next 1,000 years, they gradually migrated to fill the void left by the incredible catastrophe that had overtaken the planet.

The surviving animals struggled out of hiding to scratch around for food, and hardy seeds began to germinate again. The animals that fared best were small, and they were mostly omnivores or scavengers, able to feast on the huge banquet of animal and plant remains. The large plant-eaters fared worst in the aftermath; they had the largest appetites and the hardest time satisfying them. Being big, they were also the most visible targets for the hungry human survivors. Almost all conditions were against them, so before long the remaining megafauna in the north dwindled and disappeared.

By the time the effects of the catastrophe had subsided —maybe months, years, or decades in total—the collision had irreversibly altered the planet. The old Earth was gone, destroyed by an exploding star's invisible radiation, by white-hot fire from the sky, and by floods raging across the Earth.

A new world was born from the mud and ashes. The new children who entered the world to replace the missing of course knew nothing of the Event. Their parents were determined, however, that their offspring should know about the Great World Fire and the Great Flood, and that they remember to honor the Creator who had spared them. Grandfathers and grandmothers told stories of the Event to their grandchildren, who passed them on to their own children. For many generations, when children heard stories of the Event for the first time, they sat wide eyed and enthralled. They were amazed that such things could occur.

Eventually, many generations passed, and the children came to doubt the old stories. Surely, they thought, the Old Ones just made them all up. These terrible things could never really have happened.