You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

I'm still reading the book (it's well written and at times, funny) and the next video promises to be very interesting. Perhaps the most astonishing is how the actual zodiac constellations has been used for tens of thousands of years (at least 40 thousand as far back as the author could document) albeit with slightly different symbols.

Spoiler: the fox constellation is today's aquarius, the radiant of the Taurids during the younger dryas.

Edit: here it is

Spoiler: the fox constellation is today's aquarius, the radiant of the Taurids during the younger dryas.

Edit: here it is

Last edited:

One of the most fascinating archaeological sites is Gobekli Tepe in Anatolia.

After DECODING GÖBEKLI TEPE WITH ARCHAEOASTRONOMY: WHAT DOES THE FOX SAY? (read here: Datestamp: World's oldest monument memorializes Younger Dryas comet impact - The Cosmic Tusk), author Martin B. Sweatman from the University of Edinburgh published another hypothesis on the level of astronomical representation in prehistoric art from different sites:

https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1806/1806.00046.pdf

The paper has to be read more carefully though, but it could shed some light on some aspects of the past.

mkrnhr, have you read this guy's book "Prehistory Decoded" carefully? I just started it, and right away I found some small issues. Could you please read his explanation of precession and offer some feedback on it? I thought I understood precession pretty well, but after reading his explanation, I was confused

mariowil7

Jedi Master

mkrnhr, have you read this guy's book "Prehistory Decoded" carefully? I just started it, and right away I found some small issues. Could you please read his explanation of precession and offer some feedback on it? I thought I understood precession pretty well, but after reading his explanation, I was confused

Laura. I found interesting this youtube interview with the author of the book that you mention...

Watching it as we speak... seems to be very explanatory to me (specially as I'm a more inclined Multimedia learner guy...)

Podcast #5, Interviewing Martin Sweatman, author of 'Prehistory Decoded,' as well as several published, peer reviewed scientific papers that deal with the artwork on the megalithic columns at Gobleki Tepi. We cover a lot of ground in this conversation, I'd recommend watching Martin's videos on his work on his channel as a primer! (link below) Martin's work is changing the game when it comes to the capabilities of our ancient ancestors, he decodes the European paleolithic cave art and megalithic art at Gobleki Tepi into a coherent dating system, based on constellations and 'the great year', the 25,920 year cycle of the precession of the equinoxes.

Part 5 is out.

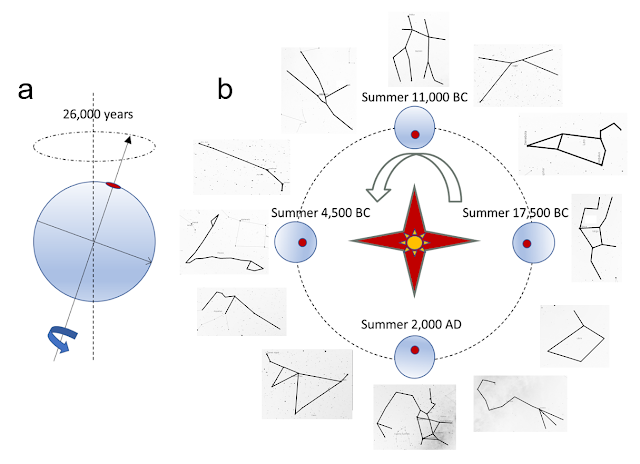

Here is Sweatman's graphic from his blog for his precession of the equinoxes.

Yes, I have the book and the graphic. No problem there. It's his explanatory method that bugs me.

mkrnhr, have you read this guy's book "Prehistory Decoded" carefully? I just started it, and right away I found some small issues. Could you please read his explanation of precession and offer some feedback on it? I thought I understood precession pretty well, but after reading his explanation, I was confused

Martin Sweatman talks in his book about two different types precession: so called Precession of the Equinoxes ("wobbling" of the Earth rotational axis) and orbital precession of heavenly bodies. The explanation of Precession of the Equinoxes in his book is a standard one as far as I understood it:

As we all know, Earth rotates on its own axis once a day, and it takes slightly over 365 days to orbit the Sun. But Earth’s own axis of rotation is not perpendicular to its orbit around the Sun. That is, the plane that goes through Earth’s equator is inclined with respect to the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun. So, the Earth is tilted somewhat, currently by 23 degrees, compared to its orbit. This gives rise to the seasons, as well as the solstices and equinoxes.

Because the Earth spins on its axis, it is not perfectly spherical. It bulges slightly at the equator because of the apparent centrifugal forces on Earth’s surface as it rotates, which are strongest near the equator. And because the equator is not in the same plane as Earth’s orbit, this means there are times in the year when the equatorial bulge nearest the Sun is above the plane of Earth’s orbit and other times when it is below it. Gravitationally, the Sun ‘pulls’ down on this bulge when it is above the plane of Earth’s orbit, and ‘pulls’ up on this bulge when it is below. Rather like a pendulum, this causes the axis of Earth’s rotation to ‘precess’. In fact, it is exactly like a spinning top; Earth’s axis of rotation ‘wobbles’, albeit very slowly.

A good way to visualise this is to imagine that Earth’s axis of rotation points at a star. This is known as the ‘Pole Star’. As Earth’s rotational axis precesses (wobbles), it begins to point at other nearby stars, which then become the new Pole Star. Eventually, after nearly 26,000 years, Earth’s axis of rotation will complete an entire cycle of precession and we will be back to our original Pole Star. The rotational axis will have ‘pointed out’, or described, a circle in the sky on which all the Pole Stars lie. Today, the Pole Star seen from the northern hemisphere is Polaris in the constellation Ursa Minor. But in 11,000 BC it was Vega in the constellation Lyra, while in 16,000 BC it was Deneb in the constellation Cygnus.

In addition to a very gradual change in the identity of the Pole Star, Earth’s axial precession also has other observable consequences. The one that concerns us most is precession of the equinoxes. Imagine you are standing at the North Pole. The Pole Star, currently Polaris, is vertically above you, day or night, while all the other stars appear to trace great circles in the sky with a wide range of diameters as Earth (and you) rotate. You will be closest to the Sun on midsummer’s day, the summer solstice, when Earth’s axis is tilted most towards the Sun. The constellation observed ‘behind’ the Sun on this special day in the year in our current epoch is Gemini, as seen from the northern Hemisphere.

But 13,000 years ago, Earth tilted towards a different northern Pole Star, Vega. The summer solstice then occurred when Earth was on the other side of the Sun – halfway along its orbit around the Sun compared to today. The constellation behind the Sun then was Sagittarius. Over the course of nearly 26,000 years, all the zodiacal constellations appear in their respective order behind the Sun on the summer solstice. Of course, we cannot see directly which constellation is behind the Sun, as the stars are not visible during the day. But by observing the stars just before sunrise or after sunset it is possible to work out which constellation the Sun will be in front of.

And, because the summer solstice constellation slowly changes with precession, so does the winter solstice and the spring and autumn equinoxes. They all gradually rotate through the zodiacal constellations – this is known as precession of the equinoxes (see Figure 9).

The orbital precession has two types: apsidal and nodal. Here is his explanation:

We therefore know that the orbit a body follows depends largely on its size. A large dense body, such as a huge asteroid, will follow an orbit that is almost perfectly elliptical. But, the gravitational effects of the planets, especially Jupiter, will cause this elliptical orbit to evolve – it will not follow the same elliptical orbit for all time – it will precess. This means the direction in which its elliptical orbit points, defined by its orbital axis, changes very slowly. Two types of orbital precession are important for our story (see Figure 15). The first is apsidal precession, also called precession of the perihelion. Imagine a flower head at the top of a stalk with one elliptical petal that points in a particular direction. The outline of the petal represents an elliptical orbit. Now imagine this petal slowly rotating around the flower head, even though the flower head is held fixed. This is like an elliptical orbit slowly undergoing apsidal precession, even though the plane in which the orbit resides is fixed. Now imagine twirling the stalk between your fingertips so that the whole flower head, which is inclined, rotates. This is like another kind of orbital precession known as nodal precession, or precession of the longitude. Here, the plane in which the elliptical orbit resides slowly rotates.

And here is the referenced Figure 15 which illustrates it better:

Figure 15. Earth’s orbital plane is shaded dark grey. The orbit of an asteroid or comet is represented by the thick black line. Apsidal precession (upper arrow) causes the direction of its elliptical orbit, or axis, to rotate around the Sun within the same fixed plane, shaded light grey. Nodal precession (lower arrow) causes the entire orbital plane, in which the asteroid or comet’s orbit resides, to rotate around the sun.

Martin Sweatman talks in his book about two different types precession: so called Precession of the Equinoxes ("wobbling" of the Earth rotational axis) and orbital precession of heavenly bodies.

That‘s how I understood it too. He talks about at least two different types of Precessions.

OK, will take a look again. That was the part from the book I skippedmkrnhr, have you read this guy's book "Prehistory Decoded" carefully? I just started it, and right away I found some small issues. Could you please read his explanation of precession and offer some feedback on it? I thought I understood precession pretty well, but after reading his explanation, I was confused

From what I've read before from Napier and others, he should be talking about the precession of the Taurid meteor stream's orbit relatively to Earth's orbit, which is distinct from the precession of the equinoxes.

Edit: Here is an explanation of the Taurids apsidal precession by Duncan Steel:

The movement of meteor shower radiants over aeons

The movement of meteor shower radiants over aeons A PDF (368 kB) of this post can be downloaded by clicking here. Various email messages have alerted me to some discussion of the Taurid meteor show…

www.duncansteel.com

Last edited:

I tried to show the apsidal and nodal precession in very simplified drawings:

Here we suppose for the sake of simplicity that the orbit of the comet debries is perpendicular to the orbit of the Earth around the Sun.

Apsidal precession:

The orange line is the ecliptic, the orbit of the Earth around the Sun (or the sun around the earth), viewed from the side. The ellipse is the average orbit of some cometary debries, one the plane of the screen (perpendicular to the ecliptic. At t1, there are no collision because the debries intersect the ecliptic inside the orbit of the Earth. As this ellipse rotates slowly around the Sun (apsidal precession), it intersects the orbit of the Earth four times at t2, t3, t4, t5 before going back to its initial orientation. Here, the plane of the orbit has an inclination 90°, but the same thing happens for every inclination different than 0.

In addition to the apsidal precession, there is also the nodal precession:

Here again the orbit is perpendicular to the plane of the ecliptic, and perpendicular to the screen. We are looking to the earth's orbit directly from above (or below). The plane of the elipse (straight lines here) slowly rotate around the sun so that when an encounter occurs at some epoch, the earth is at different parts of its orbit. This is what mainly determines why the Taurids were radiating from different constellation in the far past. Again, same thing applies for any inclination.

FWIW, and not sure if it is related but here is a quick plot I did a long time ago on the date of the Perseids meteor shower (not corrected for leap years, it should be converted to julian dates etc.) that kind of shows that meteor stream encounters shift through time and that at distance epochs they would appear at different parts of the year, thus from different stations in the sky:

Here we suppose for the sake of simplicity that the orbit of the comet debries is perpendicular to the orbit of the Earth around the Sun.

Apsidal precession:

The orange line is the ecliptic, the orbit of the Earth around the Sun (or the sun around the earth), viewed from the side. The ellipse is the average orbit of some cometary debries, one the plane of the screen (perpendicular to the ecliptic. At t1, there are no collision because the debries intersect the ecliptic inside the orbit of the Earth. As this ellipse rotates slowly around the Sun (apsidal precession), it intersects the orbit of the Earth four times at t2, t3, t4, t5 before going back to its initial orientation. Here, the plane of the orbit has an inclination 90°, but the same thing happens for every inclination different than 0.

In addition to the apsidal precession, there is also the nodal precession:

Here again the orbit is perpendicular to the plane of the ecliptic, and perpendicular to the screen. We are looking to the earth's orbit directly from above (or below). The plane of the elipse (straight lines here) slowly rotate around the sun so that when an encounter occurs at some epoch, the earth is at different parts of its orbit. This is what mainly determines why the Taurids were radiating from different constellation in the far past. Again, same thing applies for any inclination.

FWIW, and not sure if it is related but here is a quick plot I did a long time ago on the date of the Perseids meteor shower (not corrected for leap years, it should be converted to julian dates etc.) that kind of shows that meteor stream encounters shift through time and that at distance epochs they would appear at different parts of the year, thus from different stations in the sky:

Last edited:

gnosisxsophia

Jedi Council Member

The plane of the elipse (straight lines here) slowly rotate around the sun so that when an encounter occurs at some epoch, the earth is at different parts of its orbit. This is what mainly determines why the Taurids were radiating from different constellation in the far past. Again, same thing applies for any inclination.

From an observational angle, the precession discussion reminds me of the interesting assertion (in old SOTT article) challenging the 'wobbling' Earth theory;

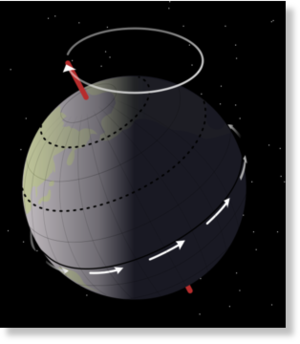

The current theory, called the Lunisolar Theory, states that the Earth's rotational axis also rotates tracing out the shape of a cone (see image to the right), changing its orientation very slowly - kind of like a spinning top. They call it the 'Luni-solar' theory because it is said that this top-like motion is caused by gravitational tidal forces coming from the Sun and the Moon. The idea is that it takes the Earth roughly 24,000-26,000 years to move its axis a full circle along this cone-like path. So the Lunisolar Theory would ostensibly seem to explain the precessional movement, although there is a problem (actually, several).

© NASA, Mysid

The LuniSolar Theory of precession: is the Earth's axis really tracing out a cone-like path every 24,000 years?

First of all, if this axial top-like motion were occurring, then we'd expect to lose a small amount of time each day. We would start to notice a small shift in our calculations for eclipses, planetary transits and such, which have to be measured fairly accurately. The motion of the planets that we observe in the sky should also precess along with the rest of the stars and galaxies in the background, but according to Karl Heinz and Uwe Homann in their Venus transit studies, they don't. According to Crutenden, we don't take into account precessional movement when calculating the positions of the planets or anything within our solar system for that matter. So any planets or other objects within the Solar System do not appear to precess with respect to the Earth. The only objects that follow precessional movement are those outside the Solar System. If this is the case, then precession cannot be due to this top-like motion that the Lunisolar Theory dictates.

Which makes for an intriguing statement by Edward Nightingale;

The movements of the star Sirius and the Pleiades star cluster are at odds with the current theory of precession in that they do not demonstrate the so-called wobble motion of the Earth’s axis. This implies that Sirius and the Pleiades are on a similar trajectory as our solar system. In fact, that is exactly what I have discovered encoded in The Giza Template. I propose that our solar system, the star Sirius and the Pleiades star cluster system were birthed from the same stellar nebula, that being the Great Orion Nebula, M42. These three systems are each on their own spiral trajectory or path, each being separated by time and distance directly related to the Great Year Cycle of 25,920 years. These star systems are moving away from the M42 Nebula in a spiral motion with our ecliptic rolling along like a wheel on a spiral path."

And also quite a mind bender regarding forecasting cometary 'source' or origin!

...It's his explanatory method that bugs me.

On a lighter note, I thought the statistical example presented in the videos - asserting the authors own 'correctness' - was pure gold myself?

Particularly considering the fixation on 'the fox', being part of Aquarius, becoming even more confusing upon comparing text to image?

With the image below (provided in Sweatman's document) contradicting the stated reasoning by clearly showing pillar 38's sequence as - Fox (not Aurochs), Boar and 2 different birds?

Which made the only image common to the pillars under discussion, actually 'the fox' and not the aurochs + crane at all?

Sort of negating the rest of the argument I thought...

The apsidal/nodal precessions of the orbits of these objects are independent from the the equinoxial precession of the Earth. It's the same weather it's the "earth wobble" or the "global spin of the whole solar system" or a mixture of the two that explains the best the precession of the equinoxes.From an observational angle, the precession discussion reminds me of the interesting assertion (in old SOTT article) challenging the 'wobbling' Earth theory;

With the image below (provided in Sweatman's document) contradicting the stated reasoning by clearly showing pillar 38's sequence as - Fox (not Aurochs), Boar and 2 different birds?

On the pillar 38 it's not the same fox as depicted in pillar 2 and pillar 18 (open mouth, straight tail) but the interpretation of it as an Auroch by Karl Shmidt doesn't convince either, even if the depiction is damaged. To my eye at least, the carving is of a different quality relatively to the other pillars. Maybe it has been carved at a later date for another event. The author suggests that pillar 38 represents the southern taurids path at the same date but he even conceides that "but we find it difficult to see right now how the boar represents the southern asterism of Aquarius."

The other "good" quality pillar are consitent between themselves, no so with pillar 38 IMHO.

"

I've read it too. What I found quite interesting was his mentioning of several possible dates in the past when "Satan" (as he termed the giant comet that maybe entered the solar system tens of thousands of years ago) and its remains might have interacted closely with earth. Although it doesn't directly fit the C's mentioning of the 3600-year circle of a comet cluster, taking possible dating problems into account, it might not be too far of the mark and might be at least partly what he is looking at.

Also, his idea that some of the signs/symbols associated with star constellations you can see from earth at night have changed over the millennia is quite interesting too. Although he doesn't give an explanation for why this might have happened, the why and how of this sounds like an interesting area to follow up upon.

Also, his idea that some of the signs/symbols associated with star constellations you can see from earth at night have changed over the millennia is quite interesting too. Although he doesn't give an explanation for why this might have happened, the why and how of this sounds like an interesting area to follow up upon.

Trending content

-

-

Thread 'Coronavirus Pandemic: Apocalypse Now! Or exaggerated scare story?'

- wanderingthomas

Replies: 30K -

-