The fact was lost on the transgender that in hospitality industry, the customer is always right!Just read a good example of an over-reactive transgender person who is so into the "program" that s/he/it is making life difficult now and probably in the future, and also reflecting badly on other trans persons.

‘Bigoted trash!’ Transgender coffee shop employee fired for kicking out conservative customer

A coffee shop in Nebraska has fired a transgender employee after she began “yelling profanities” at a regular customer over their conservative and “bigoted” political beliefs.www.rt.com

In the article there is a link to this person's FB post about the incident that gives a pretty good idea of the twisted thinking.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Gay "Germ" Hypothesis

- Thread starter H-KQGE

- Start date

Palinurus

The Living Force

Since the use of the words "natural" vs. "unnatural" played such an important part in the current discussion I went out to search for more info about homosexuality in animals. This is part of what I found:

There’s no evidence that a single ‘gay gene’ exists

Homosexuality exists in many species - Homophobia in one | QNews

There is no homophobia in the animal kingdom | DW | 02.08.2017

You can take a guided tour of "homosexuality in the animal kingdom" at the Amsterdam zoo for Pride

Artis zoo celebrates Pride by showcasing sexual diversity in nature

Amsterdam zoo offers 'gay animal' tours - DutchNews.nl

Denver Zoo's Same-Sex Flamingo Couple Lance Bass and Freddie Mercury Might Raise Chick Together

Video 5:56 min.

GAY ANIMAL TOUR IN AMSTERDAM ZOO | PRIDE AMSTERDAM 2018

There’s no evidence that a single ‘gay gene’ exists

Homosexuality exists in many species - Homophobia in one | QNews

There is no homophobia in the animal kingdom | DW | 02.08.2017

You can take a guided tour of "homosexuality in the animal kingdom" at the Amsterdam zoo for Pride

Artis zoo celebrates Pride by showcasing sexual diversity in nature

Amsterdam zoo offers 'gay animal' tours - DutchNews.nl

Denver Zoo's Same-Sex Flamingo Couple Lance Bass and Freddie Mercury Might Raise Chick Together

Video 5:56 min.

During the Amsterdam Pride homosexual behavior in the animal kingdom will be in the spotlight in ARTIS.

The AGP team joined the tour and learned a lot about homosexuality and gender diversity in the animal kingdom.

Homosexual behavior in the animal kingdom is common and has been observed among 1,500 species of birds and mammals. Males sniff, jump and lick each other and females are no different from each other. In addition, we see that there can also be a gender transition in animals during their lifetime.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator

Since the use of the words "natural" vs. "unnatural" played such an important part in the current discussion I went out to search for more info about homosexuality in animals. This is part of what I found:

There’s no evidence that a single ‘gay gene’ exists

Homosexuality exists in many species - Homophobia in one | QNews

There is no homophobia in the animal kingdom | DW | 02.08.2017

You can take a guided tour of "homosexuality in the animal kingdom" at the Amsterdam zoo for Pride

Artis zoo celebrates Pride by showcasing sexual diversity in nature

Amsterdam zoo offers 'gay animal' tours - DutchNews.nl

Denver Zoo's Same-Sex Flamingo Couple Lance Bass and Freddie Mercury Might Raise Chick Together

Video 5:56 min.

GAY ANIMAL TOUR IN AMSTERDAM ZOO | PRIDE AMSTERDAM 2018

And you don't think that a lot of that is not spin and propaganda?

Since the use of the words "natural" vs. "unnatural" played such an important part in the current discussion I went out to search for more info about homosexuality in animals. This is part of what I found:

The use of those two words has nothing to do with any purported 'homosexuality' in animals. Any such 'homosexuality' is irrelevant to this discussion for obvious reasons.Also, the 'homo' in 'homosexual' refers to the genus of bipedal primates that includes modern humans. So flamingos and the like don't really cut it.

Last edited:

I just thought that the occurrence of homosexual behavior in animals would weaken the strenght of the original argument about a possible "germ" hypothesis as a plausible cause for humans. That''s all.

But it actually doesn't do that. Consider the example of toxoplasma which is the one trotted out in the "germ theory".

The homo- in homosexuality actually comes from the Greek word homos for 'same'. (Hetero means 'other'.) The homo in Homo sapiens is Latin for 'man/person'.The use of those two words has nothing to do with any purported 'homosexuality' in animals. Any such 'homosexuality' is irrelevant to this discussion for obvious reasons. Also, the 'homo' in 'homosexual' refers to the genus of bipedal primates that includes modern humans. So flamingos and the like don't really cut it.

PhoenixToEmber

Jedi Council Member

Well, I think it is brave and the right thing to do to at least QUESTION oneself, and consider the above. It is a possibility, when you take into account "nature", polarity as Laura explained above, etc. And if it is possible, then I think it would benefit a lot to keep it in mind, because it can orient one towards different or better steps if one is sincere in his/her efforts.

That said, we are all at a "disadvantage", or not. I think that we often choose the life we have. In fact, perhaps more so at this point in History than in the past? The parents we "chose", the environment we chose to incarnate in, the social milieu, and even our genetics... all those things have made it so that each of us, in different ways, have had a billboard drop on our heads about something, sometimes more than once.

And I think that that is probably exactly how we needed it to be. We either "played in the mud" due to the programming and karma and what not, until we had enough, or learned certain things like not trusting and isolation, or a super narcissistic behavior, just to give a few examples. Whatever it is, we needed the experience in order to hopefully, one day, choose to act differently and develop sides of our self that we neglected. So, why would it be different for gays, or anyone else? The trick, of course, is to discover what we came here to learn, and make the best of it.

Just some hypotheses: considering the amount of propaganda and pushing regarding "gay pride and freedom" nowadays, one person may be homosexual because he/she needs to learn in this life to not be so attached to physicality, or to not define themselves by what they are outside, justifications, etc. (which you explained quite well with your own example in that last reply, and I think it's quite insightful and something to work on). Another person may have been born gay because the only way they can learn about this is to "play in the mud" until they are fed up with it. Another one, well, they may just like it and it's not in their life path to change.

There are any number of possibilities, but I think that as long as one is willing to be open to the truth even when it hurts, and to be ruthless with oneself, disciplined, and learn to say yes or no more appropriately, then it doesn't really matter where one stands to begin with. EVEN if being a homosexual puts someone at a disadvantage in terms of the Work, say, who is worse off? The heterosexual with lots of potential who couldn't withstand the death of the tiniest illusion, and who decided to never learn anything, or the homosexual who is still here, trying to find out the truth, face it and embody it to the best of his or her ability? I'd much rather be the one who fights than the coward. And what may be seen as a "disadvantage" could be turned into an "advantage", when there is a Will, and when one is as aware as possible. When the suffering experienced is turned into something good for others.

Again, I'm not saying that the disadvantage is real. I have no idea of whether it is or not! But I DO think that being open to accepting our limitations in ANY area and for ALL of us is productive. And in the end, we can be more realistic when putting our real talents to use, while keeping in mind our quirks or "disadvantages". Actually being grateful for some of them, because in some cases, they were a trade-off for gaining some good qualities too.

Regarding all you shared, I think that perhaps something that could help with this is to share more on other topics. Imagine that nobody here knew you were homosexual, and participate in threads just to help others, because it is in you to do that. It shouldn't matter that you have this or that sexual orientation. What matters is that you constantly try to gain knowledge, assimilate it and share it with others. Try to find what you have in common with other people, not your "differences" only. Maybe that way, you can not just lose some of the identification and insecurities, but also discover who you trully want to be, not just in this life with your particular lessons, but as a conduit for the universe, as small as our individual influence may seem to be. FWIW!

This was very motivational. Thank you, Chu. I have nothing to add, going to just let it sit with me for a while.

Not sure if you missed the article I linked few pages back. Homosexuality in a real sense ( males choosing to mate with other males for life even when females are present) exists only in two species of animals - humans and sheep. And it may have something to do with changes in hypothalamus structure.I just thought that the occurrence of homosexual behavior in animals would weaken the strenght of the original argument about a possible "germ" hypothesis as a plausible cause for humans. That''s all.

The homo- in homosexuality actually comes from the Greek word homos for 'same'. (Hetero means 'other'.) The homo in Homo sapiens is Latin for 'man/person'.

You're right! Silly me.

Not sure if you missed the article I linked few pages back. Homosexuality in a real sense ( males choosing to mate with other males for life even when females are present) exists only in two species of animals - humans and sheep. And it may have something to do with changes in hypothalamus structure.

Yes, and it speaks volumes that the gay community so frantically seeks for examples of "homo animals", when everyone who has to do with animals can tell you this just ain't so. Most, if not all, male animals are "macho bigots", and many animals are downright racist! All of them are almost totally selfish. But so what? We are not animals, and shouldn't be.

I guess this goes back to the confusion between natural biology and natural law/Cosmic Order. And I can understand that, because the gay community considers being gay as something unchangeable, natural - i.e. biological. So to them it's puzzling why this doesn't exist in animals, and how it could have "evolved" etc. Darwinism strikes again! All the more reasons especially for gay people to find out what is going on here, as Laura said.

Something interesting I came across that is not specifically about gay culture, but about the first steps to the destruction of normative/Nature based values and social structure:

quillette.com

quillette.com

In her new book Primal Screams: How the Sexual Revolution Created Identity Politics (excerpted in Quillette on August 27), essayist and cultural critic Mary Eberstadt documents just how damaging the sexual revolution of the 1960s, and its normalization of divorce in particular, has been to America’s children. She mentions many publications that comment on “the correlations between crumbling family structure and various adverse results,” particularly for the children of divorce. The authors she cites include former U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, social scientist James Q. Wilson, and Elizabeth Marquardt, author of Between Two Worlds: The Inner Lives of Children of Divorce.

A writer she doesn’t mention, however, is William Peter Blatty, author of the blockbuster 1971 horror novel The Exorcist. Those who have never read the novel, or are familiar only with its 1973 cinematic incarnation, probably believe the book to be a potboiler about demonic possession. But it is also an allegorical warning about the importance of the traditional family unit and the devastation wrought when it breaks down. Curiously, this aspect of the novel went largely unnoticed by the book’s earliest reviewers.

Back in 1971, the advent of no-fault divorce laws in the United States was seen in liberal circles as an unalloyed benefit for society. Thus, the book critics for most of the mainstream publications that bothered to review The Exorcist—Time, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, etc.—treated the book as either a modern day pastiche of Poe and Mary Shelley, or else as a traditional story of the battle between Good and Evil. What’s odd about this is that Blatty made no effort to hide his social conservatism. You don’t have to be a postmodern literary detective to find it in the subtext. Blatty was not a subtle writer, and he set his message out on the page for all to see, although very few have ever remarked upon it.

The Exorcist tells the story of Chris MacNeil, a recently divorced American movie star, and her 12-year-old daughter Regan Teresa MacNeil, whom Chris calls “Rags.” The story takes place in Washington, D.C., where Chris has rented a home a few blocks from the campus of Georgetown University. She is the star of a movie about unrest on campus that is being filmed at Georgetown. Neither Chris nor her daughter have yet recovered from the divorce. And Regan has begun to demonstrate troubling behavior (using obscenities, operating a Ouija board with a creepy imaginary friend, lashing out at the adults around her) that leads Chris to seek help and advice, first from psychiatric professionals.

Every few pages, the reader is reminded about the absence of Regan’s father. Early in the book, as Chris is hanging up a dress in Regan’s closet, she thinks: Nice clothes. Yeah, Rags, look here, not there at the daddy who never writes. Regan appears to be in search of a substitute for the father she has lost, and television seems to be one of the places she has been looking. Her creepy imaginary friend is called Captain Howdy, clearly a reference to two TV characters popular with children of the Baby Boom, Captain Kangaroo and Howdy Doody. After Regan explains her friendship with Captain Howdy to her mother, Blatty writes:

Over and over, Blatty specifically connects Regan’s demonic behavior with the trauma of her parents’ divorce.

[...]

In the 1960s and 1970s, almost everyone in the progressive cultural circles in which Blatty moved saw the liberalization of America’s divorce laws as a boon to society. Blatty alone seemed to recognize that, for the children caught up in these dissolving marriages, divorce was like a trip into hell. The studies Eberstadt cites in her new book confirm that Blatty was right.

[...]

In many ways, Blatty was a man of his times, and those times were confusing. In the summer of 1969 (the summer of Woodstock and the Tate-LoBianca murders), as he was holed up in a Lake Tahoe cabin, hammering out the first draft of The Exorcist on an IBM Selectric typewriter, America was in the midst of cultural and political upheaval—the arrival of the Pill, the rise and demise of the hippie counterculture, the Stonewall riots and the beginnings of the gay rights movement, the Women’s Liberation movement, and the rejection of puritanical attitudes towards sex and marriage. The liberalization of abortion laws by the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe vs. Wade would follow the publication of The Exorcist by two years—the same year William Friedkin’s film appeared in US theaters.

[...]

When asked by Damien Karras what the reason for demonic possession is, Father Merrin replies:

William Peter Blatty's Counter-Countercultural Parable

In her new book Primal Screams: How the Sexual Revolution Created Identity Politics (excerpted in Quillette on August 27), essayist and cultural critic Mary Eberstadt documents just how damaging the sexual revolution of the 1960s, and its normalization of divorce in particular, has been to...

quillette.com

quillette.com

In her new book Primal Screams: How the Sexual Revolution Created Identity Politics (excerpted in Quillette on August 27), essayist and cultural critic Mary Eberstadt documents just how damaging the sexual revolution of the 1960s, and its normalization of divorce in particular, has been to America’s children. She mentions many publications that comment on “the correlations between crumbling family structure and various adverse results,” particularly for the children of divorce. The authors she cites include former U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, social scientist James Q. Wilson, and Elizabeth Marquardt, author of Between Two Worlds: The Inner Lives of Children of Divorce.

A writer she doesn’t mention, however, is William Peter Blatty, author of the blockbuster 1971 horror novel The Exorcist. Those who have never read the novel, or are familiar only with its 1973 cinematic incarnation, probably believe the book to be a potboiler about demonic possession. But it is also an allegorical warning about the importance of the traditional family unit and the devastation wrought when it breaks down. Curiously, this aspect of the novel went largely unnoticed by the book’s earliest reviewers.

Back in 1971, the advent of no-fault divorce laws in the United States was seen in liberal circles as an unalloyed benefit for society. Thus, the book critics for most of the mainstream publications that bothered to review The Exorcist—Time, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, etc.—treated the book as either a modern day pastiche of Poe and Mary Shelley, or else as a traditional story of the battle between Good and Evil. What’s odd about this is that Blatty made no effort to hide his social conservatism. You don’t have to be a postmodern literary detective to find it in the subtext. Blatty was not a subtle writer, and he set his message out on the page for all to see, although very few have ever remarked upon it.

The Exorcist tells the story of Chris MacNeil, a recently divorced American movie star, and her 12-year-old daughter Regan Teresa MacNeil, whom Chris calls “Rags.” The story takes place in Washington, D.C., where Chris has rented a home a few blocks from the campus of Georgetown University. She is the star of a movie about unrest on campus that is being filmed at Georgetown. Neither Chris nor her daughter have yet recovered from the divorce. And Regan has begun to demonstrate troubling behavior (using obscenities, operating a Ouija board with a creepy imaginary friend, lashing out at the adults around her) that leads Chris to seek help and advice, first from psychiatric professionals.

Every few pages, the reader is reminded about the absence of Regan’s father. Early in the book, as Chris is hanging up a dress in Regan’s closet, she thinks: Nice clothes. Yeah, Rags, look here, not there at the daddy who never writes. Regan appears to be in search of a substitute for the father she has lost, and television seems to be one of the places she has been looking. Her creepy imaginary friend is called Captain Howdy, clearly a reference to two TV characters popular with children of the Baby Boom, Captain Kangaroo and Howdy Doody. After Regan explains her friendship with Captain Howdy to her mother, Blatty writes:

[...]Chris tried not to frown as she felt a dim and sudden concern. The child had loved her father deeply, yet never had reacted visibly to her parents’ divorce. And Chris didn’t like it. Maybe she cried in her room; she didn’t know. But Chris was fearful she was repressing and that her emotions might one day erupt in some harmful form. A fantasy playmate. It didn’t sound healthy. Why “Howdy”? For Howard? Her father? Pretty close.

Over and over, Blatty specifically connects Regan’s demonic behavior with the trauma of her parents’ divorce.

[...]

In the 1960s and 1970s, almost everyone in the progressive cultural circles in which Blatty moved saw the liberalization of America’s divorce laws as a boon to society. Blatty alone seemed to recognize that, for the children caught up in these dissolving marriages, divorce was like a trip into hell. The studies Eberstadt cites in her new book confirm that Blatty was right.

[...]

In many ways, Blatty was a man of his times, and those times were confusing. In the summer of 1969 (the summer of Woodstock and the Tate-LoBianca murders), as he was holed up in a Lake Tahoe cabin, hammering out the first draft of The Exorcist on an IBM Selectric typewriter, America was in the midst of cultural and political upheaval—the arrival of the Pill, the rise and demise of the hippie counterculture, the Stonewall riots and the beginnings of the gay rights movement, the Women’s Liberation movement, and the rejection of puritanical attitudes towards sex and marriage. The liberalization of abortion laws by the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe vs. Wade would follow the publication of The Exorcist by two years—the same year William Friedkin’s film appeared in US theaters.

[...]

When asked by Damien Karras what the reason for demonic possession is, Father Merrin replies:

“I think the demon’s target is not the possessed; it is us…the observers…every person in this house. And I think the point is to make us despair; to reject our own humanity…to see ourselves as ultimately bestial…without dignity; ugly; unworthy. And there lies the heart of it perhaps…For I think belief in God is not a matter of reason at all; I think it is finally a matter of love; of accepting the possibility that God could love us. He knows…the demon knows where to strike…Long ago I despaired of ever loving my neighbor. Certain people…repelled me. How could I love them? I thought. It tormented me…How many husbands and wives must believe they have fallen out of love because their hearts no longer race at the sight of their beloveds? Ah, dear God! There it lies, I think, Damien…possession; not in wars, as some tend to believe; not so much; and very seldom in extraordinary interventions…such as here…this girl…this poor child. No, I see it most often in the little things Damien: in the senseless petty spites; the misunderstandings; the cruel and cutting word that leaps unbidden to the tongue between friends. Between lovers. Enough of these.”

Regarding the article above - I've been thinking in a similar direction, that perhaps the whole "gay question" and its spiritual relevance lies not so much in gays themselves, but their (or rather their movements', or the fact of "normalization" of homosexuality) influence on society, most notably the messing with marriage, the breaking up of families, single parents and the like. This essentially cripples so much of humanity's spirit, or rather further cripples it.

I've been reading a pretty impressive book by a 19th century priest who channelled a group of supposedly highly evolved spirits under the guidance of a spirit called "Imperator" (Stainton Moses: Spirit Teachings), and there's the following passage in there. Keep in mind that this takes place in Victorian England, one of the most rigid and rules-based societies. The part in question is the one in red, but I found the description of urban life so good that I included it. Heck, if that's what those spirits thought about Victorian England, what would they say about today's world!?

Now, the thing is: this channelled source made it clear that the way marriage is handled in society is of utmost importance to spiritual development. What's crazy though is that the source seems to be critizising marital laws and customs of the time (Victorian England). I take it that there are much wiser ways of handling marriage, based on getting two souls together that strengthen each other spiritually and grow together (the source says as much in another session), than the system and norms of the 19th century, and the false beliefs about marriage that prevailed. But nowadays, it has gotten so bad that many people actually want to go back to those rigid systems! In other words, it has gotten so much worse. And all of this seems to be entangled with the 60ies/70ies movements and the "normalization" of homosexuality. Again, if there's truth to this, then it's not that homosexuals are "bad" or have a bad spirtual influence per se, but rather their effect on humanity leads to spiritual degredation. Pretty messed up and entangled all that!

I've been reading a pretty impressive book by a 19th century priest who channelled a group of supposedly highly evolved spirits under the guidance of a spirit called "Imperator" (Stainton Moses: Spirit Teachings), and there's the following passage in there. Keep in mind that this takes place in Victorian England, one of the most rigid and rules-based societies. The part in question is the one in red, but I found the description of urban life so good that I included it. Heck, if that's what those spirits thought about Victorian England, what would they say about today's world!?

It would appear that your inability to see the operations of

these adversaries renders you unable to grasp their existence,

or to appreciate the magnitude of their influence in your world.

Not till your spiritual eyes are open will you really under-

stand how great it is, and how present. To those ranks gravi-

tate, of necessity, the earth-bound and unprogressed spirits to

whom incarnation has brought no gain, and whose affections,

centred on the earth, where all their treasure is, can find no

scope in the pure spiritual joys of the spheres of spirit-life.

Hovering over their old haunts, they live over again their

wretched, polluted earth-lives, by influencing congenial spirits

still in the body, and so gratifying their lusts and passions at

second hand.

The poor wreck whose lusts have survived the death of that

body in which and for which alone he lived, have survived the

means of direct bodijy gratification, finds his resource in seiz-

ing on an impressionable medium, and goading him on to sin,

so that he may get such poor enjoyment as alone remains for

him.

[...]

Foul, weltering masses of vice and cruelty, and selfishness,

and heartlessness, and misery that your great cities are! In

them the spirit is starved and crushed; dwelling in an atmos-

phere through which life-giving influence can hardly pene-

trate, it groans in agony as it aspires to a purer and serener

air; but its groans ascend hardly above the pall of darkness

that hovers round. The aspirations are crushed out by re-

iterated temptation; good resolves are stolen away by the

adversaries nigh at hand, and the spirit cares less and less

to [do something] against the efforts of its foes. These are only too

well seconded by the recklessness and folly which offer a

premium to vice, and make virtue well-nigh impossible.

And even when the body is removed from those dens of

impurity, sensuality, and woe, which are tenanted by so many

of your fellows even within reach of your own homes, where

riches secure exemption from bodily distress, what is the result?

We do not see gross vice, shameless physical surroundings,

open degradation of soul and body, but we breathe an atmos-

phere scarcely less spiritually bad. Money-hunting is the

business of life, and pleasure is too often found in bodily gra-

tification and sensuous enjoyment. The air is thick with the

greed of gold, with lust of power, with self-seeking in all its

myriad forms. The spirit, do you ever think what is the

state of such a spirit? It has no food, no development, no-

occupation. It is dwarfed, or compelled to occupy itself in

concerns which drag it back, and give the adversaries their

best chance of fostering and inflaming passions and desires

which are to us detestable. Hardly can we reach these more

than the debased, where in the crowded alleys and lanes vice

has its home, where in the thronged exchanges and marts,

money rules supreme, and breeds its progeny of selfishness

and greed, and larceny there the adversaries have their

centres of action, from which their baleful influence radiates.

But you know it not. You are ignorant in respect of the

world of causes, and foolish in respect of what you do in your

world in providing conditions favourable to crime and sin.

Your ignorance perpetuates these conditions, and renders it

more hard for us to impress upon you the true principles which

should govern the origination and development of life upon

your globe, and the cultivation of spiritual progress. Some

of your more advanced reformers have seen the vast import-

ance which attaches to the subject of marriage; and we have

endeavoured to put forward such views as you were fitted to-

receive. Much remains to be said when the world is ready,

but that is not yet. We do but allude to the subject as being

intimately bound up with the great questions of disease, crime,,

poverty, insanity, which vex and disturb us in our dealings

with men. To the folly, and worse, to the criminal reckless-

ness, and not less criminal and more foolish conventional law

which governs the marriage customs among you, very much

is chargeable. And this no less among those whom you call

the educated and refined than among the ignorant and uncul-

tured, rather, perhaps, does the greater sin rest with the rich.

You must unlearn much that men have dreamed; you must

undo much that society has sanctioned in the trafficking that

goes under the name of marriage; and you must learn truer

and diviner rules for happiness and progress than you now

tolerate, before you wipe away the great original source of

deterioration and retrogression. Mistake us not! We are

no advocates of license, no apostles of social freedom so called.

Liberty ever degenerates with the foolish into license. We

spurn such notions with contempt, even with more than we

view the infamous buying and selling, the social slavery into

which you have degraded the holiest and divinest law of life.

Nor have you yet learned that the body is the avenue of

spirit, and that laws of health and conditions under which

bodily development are possible are essential for man incar-

nated on earth. We have spoken before of this. Now we

only say that in this, as in the other matter, you are in alli-

ance with our foes. Nineteen centuries have passed since the

pure and refined teachings which you profess to treasure were

spoken amongst men; and you are but little better in all that

makes for true progress, but little wiser in real wisdom, but

little advanced in pure religion; nay, you are worse than the

Essenes, amongst whom Jesus lived and was trained. You are

as the Scribes and Pharisees, who drew from Him his bit-

terest denunciations.

And you know it not. In matters of body and spirit matters

of vital import that touch both the life here and the life here-

after you have well-nigh all to learn.

These are some of the adversaries of whom we have told

you aforetime. They are massed in force, ever ready to thwart,

and vex, and injure us. Their ranks are being perpetually

swelled by spirits debased and degraded by human ignorance.

In all that we have said we have made no account of those

who strive to do for their race and for its development what

in them lies. We have said nothing of the acts of self-sacrifice

and devotion, the simple noble lives, the generous acts that

redeem your race, and make us hopeful of its future. Our

business now is to paint the dark side of the picture: and we

have so drawn it as best to attract your attention to it. We

earnestly warn you that its lineaments are sketched with the

pencil of truth; and we warn you in all solemnity that the

great truth which underlies this message, viz., the antagonism

between good and evil, and the fostering of evil by human folly

and ignorance, is one which vitally concerns you and us in the

future of the work which we have in charge. In what has

now been said, we have but recapitulated what has been said

before of the organised opposition from those who are our

opponents. But one special form of attack, which will become

more and more frequent, we have not yet dealt with. As

objective spiritual manifestations become more and more fre-

quent, and as the inconsiderate craving for them increases,

so will it come to pass that powerful instruments will be

developed through whom our adversaries may be enabled to

produce their frivolous or tricky manifestations, so as to dis-

credit the true spiritual work. This is one of the special forms

of opposition, and the most dangerous: for in proportion to the

undeveloped character of the spirit will be its power over gross

matter, its cunning, and, in some cases, its malignity. Power-

ful agencies are even now at work, as we are assured, who will

seize every opportunity of developing mediums through whom

phenomena the most startling may be produced, so as to con-

vince the inquirers of supernatural power so called. This

done, the rest is easy. By degrees trick and fraud are allowed

to creep in, the moral teachings are allowed to appear in their

true light, doubt is insinuated, and the uncertainty and sus-

picion which have become the fixed attitude of the mind

regarding phenomena which at first seemed so surely spiritual,

gradually extend to all manifestations and teachings.

No more sure means of discrediting the teaching of those

who are sent to instruct, and not merely to astonish or amuse,

was ever devised by cunning.

[...]

Now, the thing is: this channelled source made it clear that the way marriage is handled in society is of utmost importance to spiritual development. What's crazy though is that the source seems to be critizising marital laws and customs of the time (Victorian England). I take it that there are much wiser ways of handling marriage, based on getting two souls together that strengthen each other spiritually and grow together (the source says as much in another session), than the system and norms of the 19th century, and the false beliefs about marriage that prevailed. But nowadays, it has gotten so bad that many people actually want to go back to those rigid systems! In other words, it has gotten so much worse. And all of this seems to be entangled with the 60ies/70ies movements and the "normalization" of homosexuality. Again, if there's truth to this, then it's not that homosexuals are "bad" or have a bad spirtual influence per se, but rather their effect on humanity leads to spiritual degredation. Pretty messed up and entangled all that!

Adaryn

The Living Force

I've been reading a pretty impressive book by a 19th century priest who channelled a group of supposedly highly evolved spirits under the guidance of a spirit called "Imperator" (Stainton Moses: Spirit Teachings), and there's the following passage in there. Keep in mind that this takes place in Victorian England, one of the most rigid and rules-based societies. The part in question is the one in red, but I found the description of urban life so good that I included it. Heck, if that's what those spirits thought about Victorian England, what would they say about today's world!?

Since you mention Victorian area, I read an article the other day about life in London slums in Victorian times. I can understand why those spirits were appalled… It's quite long, but i'm copying/pasting the whole thing because it's quite enlightening and well-worth reading:

These grim realities of life in London's 19th Century slums make us squirm

It was the height of the British Empire. From London, Queen Victoria ruled over large parts of the world. Riches flowed back to England from India, the Caribbean and numerous other colonies. Global trade routes made industrialists hugely wealthy, while the aristocracy were able to make the most of their inherited wealth. However, there was a darker side to 19thcentury London. Starting in the middle of the 1700s, large numbers of people had been flooding into the big city in search of a better life. What they found was poverty and misery, especially in the slums they were forced to call home.

Many of these slums were located in parts of London that are highly fashionable today. Spitalfields, just to the east of the centre, is these days home to hip designers and artists, while what were once the slums of Holborn are now home to big businesses in the fashionable West End. It’s hard to imagine just how grim life was here in Victorian times. Rising populations meant that demand for accommodation skyrocketed – and people would do almost anything to have a roof over their head. Families lived side-by-side in abject poverty. Violence, abuse and disease were all part of everyday life in London’s slums, and desperate times called for desperate measures.

But what was everyday life like for those poor souls who called the slums their home? From sleeping arrangements to paying the bills, here we present 20 grim facts about life at the very bottom of Victorian society:

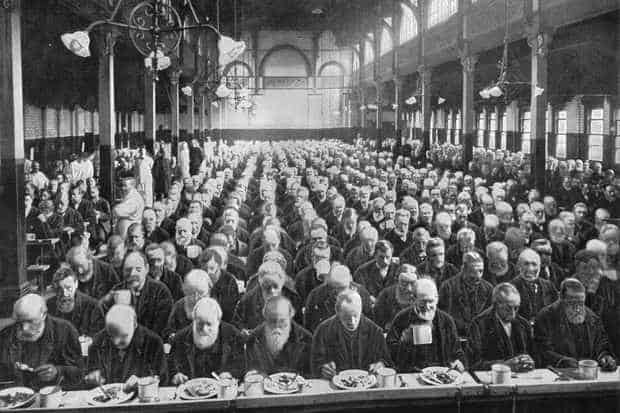

London’s slum buildings were built as cheaply as possible, and their occupants suffered. Wikipedia.

20. Slum landlords could only lease land for 21 years – so their buildings were never built to last.

Most slums were made up of large houses, or tenements, divided into individual rooms. Almost all of them had been hastily erected to cash in on the population boom of the early 19th century. Enterprising – and greedy – businessmen built on marshy meadows that had previously been used as market gardens, with the clay ground long regarded as unsuitable for building on. Notably, the city regulations meant that parcels of this land could only be leased for 21 years at most. As such, builders had zero incentive to make sure the ‘homes’ they built would last longer than this.

To begin with, slum buildings had no real foundations. They were highly unstable, and would often collapse, usually with fatal consequences. This short-term thinking and rush to cut costs as much as possible also meant that the walls were just half-a-brick thick. Needless to say, such thin walls offered no protection from the elements and would often simply collapse. Despite the shoddiness of the buildings, many of the original developers put their names to them, and these names stuck. For more than 100 years, many of London’s worst slums, including Tomlin’s New Town, were named after the greedy investor who first built on marshy land.

London’s many slums were all cold, damp and thoroughly miserable. Wikipedia Commons.

19. Many slum houses flooded, and in the winter, the water turned to ice in people’s rooms.

In 1859, Charles Godwin, the editor of the London-based magazine The Builder and an expert on architecture and housing in the capital, paid a visit to a slum. What he saw astounded him – and shocked his readers. While he was well aware that slum buildings were almost always in a state of disrepair, he was not prepared for just how bad the conditions were. Godwin told his readers: “it seemed scarcely possible that human beings could live: the floors were in holes, the stairs broken down, and the plastering had fallen… In one, the roof had fallen in: it was driven in by a tipsy woman one night, who sought to escape over the tiles from her husband.”

Such terrible conditions were commonplace. Many families lived in basement rooms, situated below street level. When it rained, the water seeped in, flooding them. And then when the temperatures dropped, the single pipe providing water to slum buildings would freeze. Holes in the walls and windows would be covered up in newspaper or anything else that came to hand. Unsurprisingly, many simply froze to death in their own ‘homes’ during the long, cold winters of London. These conditions were the focus of Charles Mowbray’s campaigning work and were instrumental in bringing about reforms.

‘Rope beds’ were a cheap but misreable way to spend the night in a doss house. Wikipedia.

18. In the Doss Houses of the slums, people took turns to sleep in the same filthy beds.

Not everyone had a room of their own in the slums. A significant number of people, including men, women and whole families, moved from place-to-place constantly. Doss houses – also known as common lodging houses – rented out beds for the night. By the end of the 19thcentury, there were 1,000 doss houses registered in London, and they were often the last resort for anyone wanting to avoid spending the nights on the streets or checking themselves into the nearest workhouse and toiling away in return for basic accommodation.

Beds in doss houses were very cheap. They were even cheaper if you rented them for a few hours, as most people did. Grown adults would sleep in shifts – and, of course, the bedding wasn’t changed between guests. Though unpleasant, the alternative was much worse. Notably, the East End prostitute Mary Ann Nichols was working the streets of Whitechapel trying to raise the pennies needed to get a bed in a local doss house when she fell victim to Jack the Ripper. According to some accounts, she had raised the money twice over but had spent it on drink before she went back out on the streets to sell her body one last time.

Four penny coffins’ were a relative luxury compared to the alternatives. Pinterest.

17. Homelessness was a major problem – and you were lucky if you could get a ‘coffin’ to spend the night in.

As hard as it might be to imagine, but the men and women living in cold, cramped and filthy tenements didn’t have it so bad – at least not compared to the homeless who tried to eke out a living in the slums. Many of the men who came to London to work on the railways, including the Irish ‘navvies’ struggled to get a proper room of their own. Homelessness was a huge problem, even in the slums. And, while the Salvation Army and other charities started helping these poor unfortunates towards the end of the 19th century, even slum rooms looked more comfortable than the temporary shelter they offered.

Perhaps the most depressing option was the ‘four penny coffin’. For the prince of 4 pence, a homeless man could lie down for the night in a wooden box. These coffin-liked beds would be lined up in long rows in old warehouses. What’s more, such ‘coffins’ were the luxury option. For a single penny, a homeless person could escape the streets of the slums for a night and sit on a chair. But they would have to pay double if they wanted to sleep while sitting up. It’s hardly surprising that many of London’s homeless just gave up and chose the indignity and cruelty of the workhouse over a life on the streets.

16. Children would bathe in – and even drink – from the same filthy streams that were used as slum sewers.

In 1849, the journalist Henry Mayhew paid a visit to one London slum. His subsequent report, In a Visit to the Cholera District of Bermondsey, shocked his readers. Above all, his description of the filthy conditions the ‘wretched people’ of the slum had to endure on a daily basis made many angry – even if nothing was done about it. Mayhew noted that a single open sewer ran through the main street of the slum. Into this, occupants emptied buckets of waste. Indeed, he noted, “we heard bucket after bucket of filth splash into it”.

More shocking still, Mayhew reported that children not only bathed in the same sewer water, but that he witnessed some people taking water out of it. According to the journalist, the slum’s inhabitants would fill pails with water from the sewer. They would leave these to stand for several days. They would then be able to skim “solid particles of filth, pollution and disease” from the top of the buckets and drink the ‘clean’ water that remained. Any water that was left over was used for bathing.

Women and girls from the slums worked 15-hour days in London’s match factories. Pinterest.

15. The poor residents of the slum were by no means idle and they tried everything to try and earn some money.

Throughout the Victorian era, puritan middle and upper-class men and women would routinely dismiss the people living in London’s slums and lazy and feckless. This could not have been further from the truth. While there certainly were many work-shy people living in poverty, there were also plenty of people working hard, just trying to get by. In the slums of the 19th century, children were expected to start work as early as the age of 7. And when a girl turned 13, she would be abler to try and find work at one of the East End’s biggest employers – the Bryant & May matchworks.

In the late-19th century, thousands of women and young girls worked in match factories, most of them travelling to work everyday from the slums. Most worked 14-hour shifts, with their pay docked for breaks, including toilet trips. The work was hard and, due to the presence of toxic white phosphorous, dangerous. What’s more, the pay was terrible, with the factory owners imposing almost slave-like conditions on their workforce. Finally, in July 1888, the Bryant & May workers had had enough. Girls as young as 13 went on strike, without any proper support. The tactic eventually worked and the matchgirls are credited as pioneers in workers’ rights in Britain.

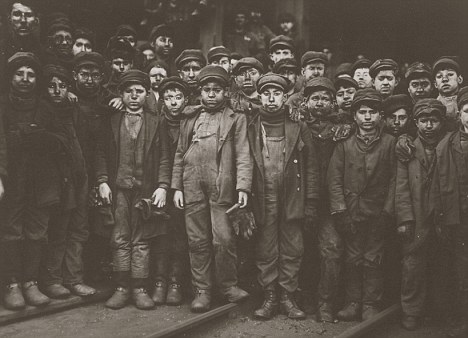

Young boys from the slums would risk their lives sweeping chimneys. History Extra.

14. Young boys from the slums often ended up cleaning the streets or sweeping chimneys to try and survive.

Employment options were quite limited for boys from the slums, especially for those not old or strong enough to find work at the docks or on a construction site. One of the best ways of earning a little bit of money was to get a job with the council clearing the capital’s streets of horse dung. According to one estimate, there were around 300,000 horses in London by the 1890s. They produced an incredible 1,000 tonnes of manure a day, clogging up the streets and making them filthy. The city council would pay boys aged between 12 and 14 to dodge between the horse-drawn carriages and shovel up the dung. As well as being dirty work, it was also incredibly dangerous as few cab drivers would slow down or swerve for a boy from the slums.

Alternatively, a young boy from the slums could try and find work sweeping the chimneys of rich Londoners. While there were laws in place to prevent abuse, these were not really taken seriously until the very end of the 19th century. That meant children from the slums – and in particular, orphans from the East End – would be sent up tight chimneys to sweep them of soot. Many boys were traumatized by the work, especially if they were employed by cruel, strict masters, and there were numerous tales of young boys becoming trapped in chimneys and suffocating to death.

Many women from the slums turned to prostitution as a last resort. Wikimedia Commons.

13. Prostitution was the only choice for many women in the slums, and many started selling their bodies before the age of 12.

Given the high levels of poverty – and the lack of routes out of it – prostitution was rife in London’s slums throughout the 19th century. Nobody can say with any certainly just how many prostitutes were working the streets of the city. However, some social historians have put the number at around 80,000. While there were a relative few middle-class ladies working as high-class escorts, the vast majority of prostitutes were from the slums. Moreover, according to surveys carried out by campaigners at the time, most were aged between 18 and 22, though most were much younger.

In the slums of East London, for example, most girls who went into prostitution did so aged 12 or even younger. This was especially true for orphaned girls, and this group were particularly vulnerable to being forced to work the streets by violent pimps. However, not all poor women were forced into prostitution – many worked the streets after working long days in London’s factories, trying to earn enough to feed their families. Whether they chose sex work or were forced into it, the risks were the same, however. Many prostitutes were assaulted, raped and even murdered, with the police rarely troubling themselves with such cases.

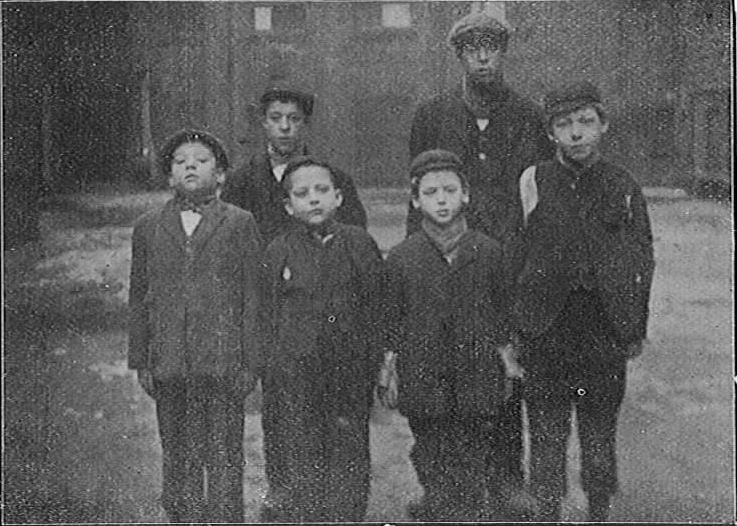

Gangs of children would pick the pockets of London’s richer citizens to survive. Pinterest.

12. Just like in Oliver Twist, London’s slums were home to gangs of child criminals.

Through his novel Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens made gangs of child criminals a central part of the popular perception of Victorian-era London. But just how accurate was the novel? Like much of Dickens’ work, it was certainly exaggerated. However, many children from the slums did indeed turn to crime in order to get by. And many did indeed pick pockets for gang masters. The records show, for instance, that the St Giles Slum, located in the very heart of the modern-day West End, was home to a man called Thomas Duggin. He was a notorious ‘thief-trainer’ and he exploited the desperation of young boys, getting them to pick the pockets of wealthy Londoners for him.

By the middle of the 19th century, the public were in a panic over ‘child gangs’. This was partly the result of the popular press whipping up hysteria in order to sell newspapers. However, the court records show that the average citizen had a right to be worried. London’s judges dealt with hundreds of cases of child pickpockets and thieves each week. Indeed, between 1830 and 1860, half of all the defendants tried at the famous Old Bailey were aged 20 or under. And most of them were boys who came from the slums. While thieves could be sentenced to death, in reality, many were imprisoned or sent to the penal colonies of Australia – in fact, children as young as 10 were sentenced to ‘transportation’, right up until the end of the 1800s.

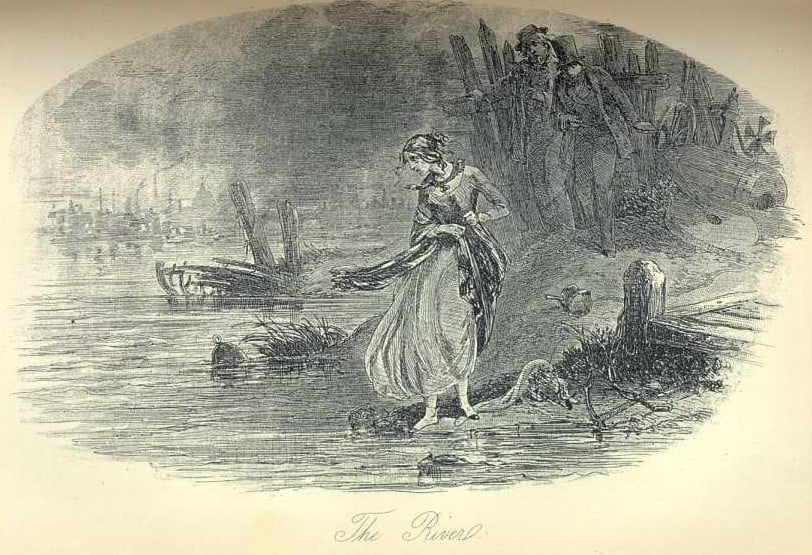

For some slum residents, suicide in the Thames seemed the best option. Literary London Society.

11. Suicide was all too common, especially among women desperate for a way out of the slums.

The author Charles Dickens was fascinated by London life, especially the lives of its poor. He would base his characters on the occupants of the city slums, and one of his most unpleasant creations was Gaffer Hexham in the novel Our Mutual Friend. Gaffer makes his living fishing bodies out of the River Thames, going through their pockets for any loose change or stripping their bodies of rings or other pieces of jewelry. Tragically, this was a real job in the Victorian era. And, in many cases, the bodies were of the men and women of the slums, people who had killed themselves rather than face another day of misery.

A disproportionately high proportion of the suicides were young women from the slums. In particular, historians of the era note that young women forced to work as prostitutes were most likely to throw themselves into the fast-flowing river in despair. However, it wasn’t just the bridges over the Thames that were popular suicide spots for fed-up slum-dwellers. Police reports from the time also reveal that Hyde Park was also a top suicide spot, with poor people drowning themselves in the Serpentine boating lake at night. The bodies would rarely be identified, and in most cases were sent straight to London’s universities and hospitals to be dissected by medical students.

In London, aound 1 in 4 slum babies wouldn’t live for more than 12 months. Pinterest.

10. Infant mortality rates in the slums remained shockingly high throughout the 19th century – 1 in 4 babies never lived more than 12 months!

Unsurprisingly, given the cramped conditions of the slums, child mortality rates were extremely high throughout the 19th century. Indeed, while the statistics show that the proportion of children surviving beyond their first birthday rose steadily over the course of the century in most London boroughs, this was certainly not the case in the inner-city slums. The statistics show that 1 in 5 infants died at 12 months or younger in the slums. What’s more, in Old Nichol Street, one of the city’s most notorious slums, 1 in 4 babies never made it to their first birthday. This number may have been even higher, since many births – and, therefore, infant deaths – simply went unrecorded, with the babies then not given a proper burial.

Even if you made it past your first birthday, the odds of making it to middle-age – or even to old age – were not good at all. For males, work was hard and dangerous. In fact, the best statistics we have suggest that the life expectancy for a casual laborer in 19th century London was just 19. And it was around the same for females. While teenage girls were unlikely to die on construction sites, falling pregnant could, and often did, prove fatal.

Did mothers in the slums really murder their infant children out of desperation? Pinterest.

9. Many infants died after being suffocated while sleeping in the same bed as their parents – but were these really tragic accidents?

One of the biggest killers of young children was a problem that became known as ‘overlaying’. Quite simply, many homes were so small and cramped that children would sleep in the same bed as their exhausted, over-worked parents. Sometimes, an adult or older child would roll over in their sleep and suffocate an infant. According to one report from the time, in the year 1887, 5 in 6 of all infant deaths that occurred in homes where families shared a single bed were the result of ‘overlaying’. But were such deaths tragic accidents or something more sinister?

To some contemporary observers, many ‘overlaying’ deaths were murders. The parents – and it was almost always the mother blamed – could not afford to feed the infant, and so suffocated it. To judgmental critics of the Victorian poor, this was yet another sign of the sinfulness of the slums. More recently, however, academics have argued that many ‘overlaying’ cases were in fact, tragic instances of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). That meant countless mothers in the 19th century either wrongly blamed themselves for the deaths of their children or were unfairly accused of murder.

Children in the slums had miserable lives and abuse was sadly commnplace. Wikimedia Commons.

8. In the cramped and dirty slums, sexual abuse of children was accepted as another grim part of life.

Sadly, it wasn’t just disease and dirtiness that the children of London’s slums had to cope with. Sexual abuse was rife in the poorer parts of the city. Just how bad it was is hard to quantify, however. Most cases of abuse would have gone unreported, while some reports from outside observers were sensationalized and exaggerated, keen to present the slums as dens of sin. However, most historians of 19th century London agree that a significant proportion of children would have been sexually abused at some point – with both young boys and girls targeted by predators taking advantage of the dark alleys, cramped conditions and lack of policing.

Most children in the slums would have been exposed to sex from a very early age. Given the cramped living conditions, they would have seen their parents having sex – surely a traumatic sight for younger infants. Many would also have endured much worse. Beatrice Webb, one of the founders of the London School of Economics, would write: “To put it bluntly, sexual promiscuity and even sexual perversion – the violation of little children – are almost unavoidable among men and women of average character and intelligence crowded into the one-room tenements of slum areas.”

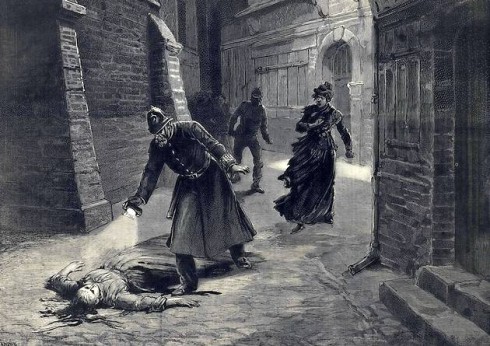

Killers like Jack the Ripper preyed on young women from the slums. Ripper Tours London.

7. Jack the Ripper was not the only killer stalking women in the London slums.

Famously, Jack the Ripper preyed on the poorest, most vulnerable members of London society. But, while ‘Saucy Jack’ may be the most famous slumland predator, he was by no means alone. Indeed, numerous killers stalked the alleyways and lanes of London’s slums during the 19th century. And, like the Ripper, many of them preyed on the lowest of the low, including desperate prostitutes. However, while the Ripper Murders won significant media attention, forcing Scotland Yard’s detectives to take action, often, random prostitute murders usually went unsolved, and were often not really investigated at all.

That said, some 19th century London murders did make the headlines at the time. Notable among them was the 1872 killing of the prostitute Hariet Buswell. The penniless girl was found dead, with her throat cut, in a boarding house. Though a ‘German-sounding’ man was identified as the murdered and a doctor even arrested, nobody was ever charged for the killing. Since Buswell was ‘just’ a prostitute and not a middle-class lady, the case was soon closed – though some say the victim still haunts the place where she was killed.

The public loved reading stories of misery and deprivation. Wikimedia Commons.

6. ‘Slumland storytelling’ was hugely popular – and the London public loved stories of fallen women and feral children.

For the first half of the 19th century, most ‘respectable’ Londoners were happy to remain ignorant about the poverty and despair they were living alongside. But then, from around the 1840s onward, a new phenomenon emerged. In the words of the historian Alan Maybe, ‘slumland storytelling’ became big business. Prominent writers and journalists would venture into the city’s slums. Their reports, rich in descriptions of feral children, fallen women and violent drunk men, were a hit with readers. The more salacious, the better such stories sold, so writers would regularly exaggerate their reports, playing on the prejudices of their readers.

It wasn’t just tabloid newspaper journalists who cashed in on this public thirst for slumland storytelling. The prominent author Jack London wrote about the miserable lives of the poorest Londoners, as did George Sims, Arthur Morrison and Jacob Riis. However, the biggest demand was for true crime stories from the slums, especially the sexual murders of young women. The Illustrated London News led the way in providing the public with pictures to go with the graphic reports. Inevitably, the lines between fact and fiction became blurred, and this wasn’t just confined to London either – Liverpool, Manchester and Cardiff all had slums, and slumland storytelling boomed here too.

5. Most middle-class Londoners believed the residents of the city’s slums were to blame for their own misfortune.

For much of the 19th century, middle and upper-class Londoners could simply pretend slums didn’t exist at all. The ‘two Londons’ rarely, if ever met. Indeed, a well-to-do Londoner would have had no reason to venture into a slum – even the poor, desperate prostitutes usually went into the main city to try and find clients. Indeed, for decades, the East End of the British capital was widely referred to as ‘darkest London’. It was a completely unknown world, a terra incognita, for ‘respectable’ Londoners, and they were happy for it to remain that way.

Then, when it became impossible to deny the existence of the slums, or question how horrible the living conditions really were, many well-off Victorians resorted to blaming the poor for the state of their housing. In popular newspapers and journals, the poor were dismissed as lazy and decadent, with the terrible conditions of the slums of their own choosing. It was only in the mid-1850s that campaigners started convincing the public that slums were the result of poverty, unemployment and social exclusion rather than the result of the ‘sinfulness’ of their occupants.

As slums were cleared, thousands of London’s poor ended up homeless. Wikimedia Commons.

4. Construction of railway tracks led to the destruction of many slums, leaving thousands destitute and homeless.

In the 1850s and 1860s, London underwent a transformation. The age of the railways had come, and lines were being built to connect the capital with other English cities. These lines were to run out of the center of London, meaning many buildings would have to be demolished to make way for progress. While the owners were compensated for their loss, anyone renting a room was not. In all, it’s estimated that around 56,000 people lost their dwellings in the space of a decade, with the poorest Londoners the worst hit by the railway clearances.

Some slums were lost completely. Agar Town, which had been home to thousands of families, including a large Irish immigrant community, was totally demolished in order to make space for warehouses for the Midland Railway. The slum’s occupants had to find cheap accommodation elsewhere. This heralded the beginning of the end of the city center slum, and the start of the rise of the suburban slum. At the same time, some slums were simply demolished to make way for upper-class housing. The historic slum of Tomlin’s New Town was torn down and replaced with fashionable ‘Tyburnia’, just north of Hyde Park. This was gentrification 1850s style – and the poor were the big losers.

3. The 1875 Artisans’ and Laborers’ Dwellings Improvement Act should have improved things but really little changed for the poorest of the poor.

By the 1870s, the British government decided that something must be done about the country’s worst slums. Significantly, this was not because they wanted to improve the lives of the people living in them. Rather, they were more concerned about citizens living outside of the slums. Experts had long been warning that the terrible conditions of the slums posed a health risk to the middle and upper-classes. What’s more, police chiefs warned that slums were becoming hotbeds of crime and perhaps even revolutionary fervor. The Conservative government, led by Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli called for the “elevation of the people”.

The 1875 Artisans’ and Laborers’ Dwellings Improvement Act gave local councils the power to buy up areas of land and then demolish the slums built upon them. Significantly, however, councils were not compelled to do so – so many chose not to. Not only was it expensive for them, but it also risked upsetting the rich men who owned the buildings of the slums. In the end, just 10 of 87 towns in England and Wales had used the powers granted them under the 1875 law to demolish slums. People would carry on living in misery for another 20 years at least.

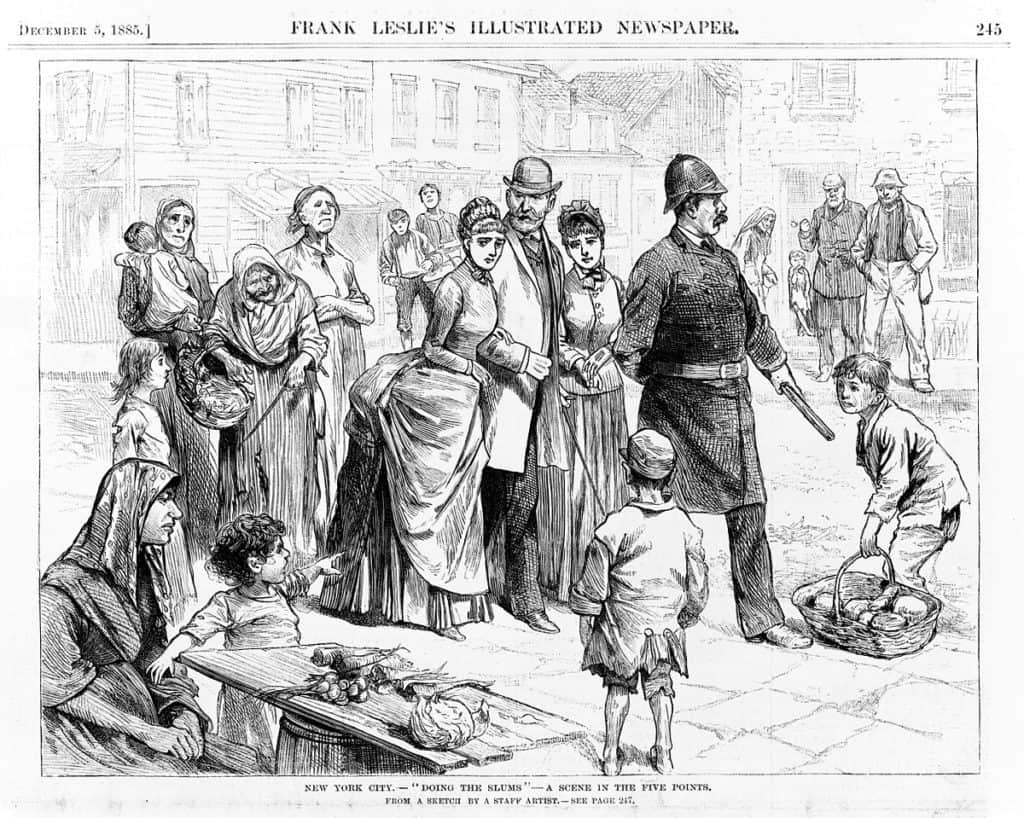

Rich tourists started visiting the slums for their own amusement in the 1880s. The British Library.

2. In the 1880s, rich Londoners started going undercover in the slums – and ‘slumming’ became a big business.

The relative failure of the 1875 Dwellings Improvement Act might have been bad news for the poorest members of London’s working class, but it was good for the tourist industry. In the 1880ss, London experienced a boom in so-called ‘slum tourism’. For the men and women of polite society ‘slumming’ became a fashionable activity, albeit one with an added sense of danger. They would don scruffy clothes and put dirt on their faces and then venture into the slums of Whitechapel or Shoreditch to see first-hand the poverty and deprivation they had only ever read about.

Undoubtedly, the ‘slumming’ phenomenon was hugely offensive. Many people did find amusement in witnessing misery and loved bragging about their brushes with danger. At the same time, however, slumming had some positive points. Up until the 1880s, many people dismissed the slum’s residents as feral drunkards. Seeing them in real-life convinced richer Londoners that most poor people were respectable and hard-working, albeit down on their luck. As a result of their slumming experiences, some notable individuals were inspired to start campaigning for better housing for London’s working class. What’s more, encounters between rich gentlemen and lower-class women were also credited with breaking down class barriers and reshaping gender relations.

1. Poverty tourism might have been in bad taste but did help bring about improvements for the masses.

Towards the end of the 19th century, a number of individuals, as well as groups, began to take an active interest in poverty and deprivation, not just in London but across England. Despite the risks, a significant number of middle and upper-class women, including aristocrats, went ‘slumming’ in London’s East End, disguising themselves in poor clothes, in order to gather data on the lives of the people living there. Eyewitness accounts by the likes of Lady Constance Battersea helped sway public opinion, with slums increasingly seen as a symptom of what was wrong with society at large.

Alongside these prominent individuals, several notable groups also stepped up their campaigning efforts. Some were Christian, driven on by their faith, though others were driven by just a sense of social justice. Schools and libraries were set up with the aim of helping the working classes escape poverty, while pressure was put on the government to improve sanitation and clamp down on criminality in the city’s worst slums. Though much was still to be done, by the end of the century, slums were no longer seen as a ‘disease’ and something to be ignored, but as social ill to be addressed head-on.

Where did we find this stuff? Here are our sources:

“Life in 19th-century slums: Victorian London’s homes from hell,” BBC History Magazine, October 2016.

“Slums and Slumming in Late-Victorian London.” Dr. Andrzej Diniejko. Victorian Web.

“Homelessness in Victorian London: exhibition charts life on the streets.” The Guardian, January 2015.

“Victorian London’s East End: what can a foul murder tell us about life in the city?” BBC History Magazine, June 2018.

“Overlaying” in 19th-century England: Infant mortality or infanticide?” Human Ecology, February 1979.

Last edited:

Trending content

-

Thread 'Coronavirus Pandemic: Apocalypse Now! Or exaggerated scare story?'

- wanderingthomas

Replies: 30K -

-