Thanks. I can see where you were coming from now.I had to laugh as I read this. After some historic inventions from Josephus, which generated much of discussion/interpretations between bible exegetes, who did not notice that it has to be finespun by Flavius Josephus in the first place she writes:

Sorry, if it sounded like I think you are stupid. I did not meant that. I was refering to this quoted sentence of a "scriptural commentator".

"First drink of water" in a desert is urine.

"Uups, there is a well...I have just smoothly overlooked."

Shure.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alton Towers, Sir Francis Bacon and the Rosicrucians

- Thread starter MJF

- Start date

Yes, I tend to agree with what you are saying. However, eradicating all worship of Baal among the Israelites proved very difficult as some form of Baal worship survived within Israel for centuries after Abraham/Moses - as shown in the story of Jezebel. Maybe the worship of Baal is still with us even today if the statue of a forty foot owl at Bohemian Grove is anything to go by, ie., if Moloch can be linked to Baal, as some commentators think (there are a number of goddesses associated with the owl too, such as Minerva and Athena).Baal (Zeus, Teshub, Jupiter - his various names) was one of the main gods, his sanctuaries (and temples) were located throughout Canaan, Syria and even Turkey (modern). Perhaps in the earlier Sumerian pantheon (the god Haddat / Adad) also refers to Baal, since by genealogy (Ugaritic mythology) Baal is the son of Ilu / El (Enlil?) or Dogon (Enki?). In different versions of the myth, Baal's "father" changes, but this is not so important for us.

At the same time, Yahweh (Shalem / Salim, Aton, Yammu - different versions of his name) was a SECONDARY God (insignificant and later). His cult was local. Perhaps even Jerusalem, which was his "residence", he stole from one of the other gods (we do not know for sure, because there is no information about this).

If you follow the Old Testament, then the main goal of Yahweh is clearly traced there (in addition to the search for artifacts of the gods) - to completely eradicate the cult of Baal and to completely destroy all the people who worshiped him (Baal) and ALL people who served in temples (that is, priests).

The very "agreement" that Yahweh concluded with the Israelites was that the guys of Abraham / Moses (as well as Joshua) would completely "cleanse" the land of Canaan from the people of Baal, and as a "reward" for this they would receive this land (Canaan) in possession (and the obligation to worship only Yahweh in this territory).

We also know that Yahweh acted as secretly as possible and did not reveal his real name to anyone (Yahweh = I exist, that is, this is not his name).

Regarding the confusing picture of what is happening - yes, it is. Nevertheless, there is a clear attempt (Yahweh) to completely erase the name of Baal from everywhere (even the figurines / statues were destroyed). At the same time, various myths describe that the priests of Baal possessed some kind of secret knowledge.

Therefore, the actions of Yahweh look more or less logical, destroying the priests of Baal, he wanted to destroy the secret knowledge that they possessed.

Attachments

The big thing that runs through the entire corpus of books by Kenneth Grant is - that SETH is the Original God.

Seth has no father, only a mother.

It was the god of the matriarchal primal religions, which were star cults in the "Aeon of Isis".

(going back to a time when the role of man in procreation was unknown - and then for a time only the knowledge of women).

Think it as 'evolution' : "monkey"-horde ->time -> human civilization

With the advent of the patriarchal monotheistic solar religions, he was banished to the desert (outside civilization) as "the Adversary".

Seth has no father, only a mother.

It was the god of the matriarchal primal religions, which were star cults in the "Aeon of Isis".

(going back to a time when the role of man in procreation was unknown - and then for a time only the knowledge of women).

Think it as 'evolution' : "monkey"-horde ->time -> human civilization

With the advent of the patriarchal monotheistic solar religions, he was banished to the desert (outside civilization) as "the Adversary".

Last edited:

The big thing that runs through the entire corpus of books by Kenneth Grant is - that SETH is the Original God.

Seth has no father, only a mother.

It was the god of the matriarchal primal religions, which were star cults in the "Aeon of Isis".

(going back to a time when the role of man in procreation was unknown - and then for a time only the knowledge of women).

Think it as 'evolution' : "monkey"-horde ->time -> human civilization

With the advent of the patriarchal monotheistic solar religions, he was banished to the desert (outside civilization) as "the Adversary".

That is quite an interesting take on the subject. Also we know that Seth in the Bible is the third son of Adam and Eve, born after Cain had killed his brother Abel.

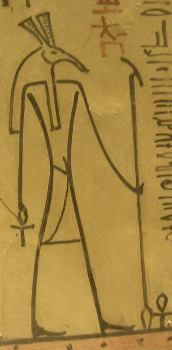

Seth or Set

In Egypt Seth (Set), son of Geb (Earth) and Nut (sky), was the brother of Osiris and god of the desert, foreign lands, thunderstorms, eclipses, and earthquakes. Seth was a powerful and often frightening deity, however he was also a patron god of the pharaohs, particularly Ramses the Great. They believed he lived in the realm of the blessed dead. Seth was a god the Egyptians prayed to so he would help their dead family members. His wife was the goddess Nephthys who was associated with mourning, the night/darkness, service (specifically in temples), childbirth, the dead, protection, magic, health, embalming, and beer. After a time, the priests of Horus came into conflict with Seth's adherents. ... Seth became the god of the unclean and an opponent of several gods. This would suggest the Egyptians saw Seth as an unclean, adversarial, desert god long before the time of Abraham. It is interesting that the Phoenician god Baal was viewed as a storm god too as was Marduk the sumerian god.

Seth or Set

In Egypt Seth (Set), son of Geb (Earth) and Nut (sky), was the brother of Osiris and god of the desert, foreign lands, thunderstorms, eclipses, and earthquakes. Seth was a powerful and often frightening deity, however he was also a patron god of the pharaohs, particularly Ramses the Great. They believed he lived in the realm of the blessed dead. Seth was a god the Egyptians prayed to so he would help their dead family members. His wife was the goddess Nephthys who was associated with mourning, the night/darkness, service (specifically in temples), childbirth, the dead, protection, magic, health, embalming, and beer. After a time, the priests of Horus came into conflict with Seth's adherents. ... Seth became the god of the unclean and an opponent of several gods. This would suggest the Egyptians saw Seth as an unclean, adversarial, desert god long before the time of Abraham. It is interesting that the Phoenician god Baal was viewed as a storm god too as was Marduk the sumerian god.

The Ennead - The nine gods who were worshipped at Heliopolis formed the tribunal in the Osiris Myth: Atum, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris, Isis, Nephthys, and Set. These nine gods decide whether Set or Horus should rule in the story The Contendings of Horus and Set. They were known as The Great Ennead.

Inanna

Isis was, of course, an Egyptian goddess but she probably derives from the Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian Ishtar and the earlier Sumerian Inanna, the goddess of love, beauty, sex, war, justice and political power. Inanna was known as the "Queen of Heaven" and was associated with the planet Venus (which curiously is where Ra the spokesman for the Law of One was supposedly based, who used to sign off by saying "in love of Adonae").

Inanna was worshiped in Sumer at least as early as the Uruk period (c. 4000 BC – c. 3100 BC), but she had little cult before the conquest of Sargon of Akkad. During the post-Sargonic era, she became one of the most widely venerated deities in the Sumerian pantheon, with temples across Mesopotamia. The cult of Inanna/Ishtar was continued by the East Semitic- speaking people (Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians) who succeeded and absorbed the Sumerians in the region. She was especially beloved by the Assyrians, who elevated her to become the highest deity in their pantheon, ranking above their own national god Ashur. Inanna/Ishtar is alluded to in the Bible and she greatly influenced the Phoenician goddess Astoreth, who later influenced the development of the Greek goddess Aphrodite and Athena can also be linked to her as well. Her Roman equivalent was Venus or Minerva.

Isis was, of course, an Egyptian goddess but she probably derives from the Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian Ishtar and the earlier Sumerian Inanna, the goddess of love, beauty, sex, war, justice and political power. Inanna was known as the "Queen of Heaven" and was associated with the planet Venus (which curiously is where Ra the spokesman for the Law of One was supposedly based, who used to sign off by saying "in love of Adonae").

Inanna was worshiped in Sumer at least as early as the Uruk period (c. 4000 BC – c. 3100 BC), but she had little cult before the conquest of Sargon of Akkad. During the post-Sargonic era, she became one of the most widely venerated deities in the Sumerian pantheon, with temples across Mesopotamia. The cult of Inanna/Ishtar was continued by the East Semitic- speaking people (Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians) who succeeded and absorbed the Sumerians in the region. She was especially beloved by the Assyrians, who elevated her to become the highest deity in their pantheon, ranking above their own national god Ashur. Inanna/Ishtar is alluded to in the Bible and she greatly influenced the Phoenician goddess Astoreth, who later influenced the development of the Greek goddess Aphrodite and Athena can also be linked to her as well. Her Roman equivalent was Venus or Minerva.

Inanna-Ishtar, Isis, Mary Magdalene: Recovering the Lineage of the Lost Goddess and Other Stolen Stories

By Dr. Joanna KujawaIt is almost as if Mary Magdalene, throughout the ages, has become a focal point for lost goddesses and their presence in our lives. Despite the tragic and untrue confusion about her status as a prostitute, there is a link in this to ancient, sexual ceremonies of sacred marriage.

The stories of the resurrection of the young king in the presence of a Goddess (which seemed so uniquely Magdalene) have been previously recounted ages ago in Ancient Sumer, Babylon and Egypt, with a Goddess as a resurrectrix. And they all seem to lead to the Sumerian Goddess Inanna, also known as Ishtar (in Assyria) and Isis (in Egypt).

These stories were perpetuated for centuries, and eventually reused in the Bible. By reused, I mean that much older versions of the same storylines were included in the Bible, but without the female component which had featured in a prominent way in original versions.

The stories of the resurrection of the young king in the presence of a Goddess (which seemed so uniquely Magdalene) have been previously recounted ages ago in Ancient Sumer, Babylon and Egypt, with a Goddess as a resurrectrix. And they all seem to lead to the Sumerian Goddess Inanna, also known as Ishtar (in Assyria) and Isis (in Egypt).

These stories were perpetuated for centuries, and eventually reused in the Bible. By reused, I mean that much older versions of the same storylines were included in the Bible, but without the female component which had featured in a prominent way in original versions.

The story of Inanna the Sumerian goddess is at least 4300 years old, and is mostly known not only through archaeological discoveries but also in a far more sophisticated way: through the poetic hymns of Inanna’s High Priestess, Enheduanna, the daughter of King Sargon of Sumer.

But who was the Goddess Inanna?

According to Sumerian stories, Inanna was the daughter of the gods An and Enki. She was a goddess connected to the Tree of life and the resurrection stories, several hundreds of years before the Biblical Genesis was written. For comparison, Enheduanna’s hymns to Inanna were written at least 500 years before Abraham was born, and the worship of this goddess can be dated back to at least 3500 BCE.

Betty De Shong Meador, the author of Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart : Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess, found that both the imaginative Van Dijk and mainstream scholars such as Simo Parpola connect the origins of the Tree of life to Inanna.

In mythical tales and sculptures, Inanna is often portrayed with a reed post, which is interpreted as a symbol of the ultimate point of orientation connecting heaven and earth. This image implies a very positive spiritual interpretation of the unification of the earthly and the spiritual through the Goddess, and mentions no sin or punishment.

For the Sumerians, as a Goddess, Inanna was a unifying force between all deities, a force which cancelled out the debate between monotheism and polytheism. She was All, both the curse and the blessing as the translator of Enheduanna’s Hymns to Inanna, Meador claims. And she is the divine matter from which all life has sprung, which also makes her the Divine Mother, and she was worshipped as such.

And being All, she was both light and darkness, and quite capable of mischief. It was she who stole the Me – the Sumerian tables of Law and civilization from Enki, according to Joy F. Reichard in Celebrate the Divine Feminine: Reclaim Your Power with Ancient Goddess Wisdom. This story is very similar to the Biblical version of Jacob stealing the blessing from his brother, except that, again, this version happened much earlier.

Other researchers, such as Reichard, say that Inanna was often depicted with lions at her feet to represent her power, which brings to mind the Hindu Goddess Durga.

Inanna has had many incarnations and represented several archetypes apart from the Divine Mother (associated with fertility). She was also the Warrior Goddess (like the Greek Athena) or the Lover Goddess not ashamed to show her sensuality and delicious erotic high for her bridegroom and beloved, Dumuzid.

There are other connections between Inanna and Mary Magdalene. The strongest of them is the notion of resurrection.

It is not known how old the notion of resurrection is, but it is certainly older than Christianity itself. Joseph Campbell in Goddesses: Mysteries of the Feminine Divine, says that he has often lectured on the old topic of the pre-Christian stories of resurrection in Jesuit seminaries, and no one has been surprised! They already knew the story, Campbell admits, but they believed that Jesus’ story was more unique.

I am not sure what this means exactly, except that perhaps the same story has been repeated in the Cosmic Consciousness, with historical figures re-enacting it over and over again until we fully understand its meaning.

In Inanna’s story, she descends into the Underworld to attend the funeral of her sister’s husband — one of the rulers of the Underworld. But after Inanna reaches the Underworld, she is not allowed to return and dies. However, through the divine intervention of the God Enki, her father, she is brought back to life, but needs to find replacement for herself. She chooses her beloved Dumuzid, who, in her absence, has usurped her throne. Eventually, Dumuzid too is allowed to return to earth, but only in spring and summer; in autumn, he must die again (Reichard, 2013).

I am not sure what this means exactly, except that perhaps the same story has been repeated in the Cosmic Consciousness, with historical figures re-enacting it over and over again until we fully understand its meaning.

In Inanna’s story, she descends into the Underworld to attend the funeral of her sister’s husband — one of the rulers of the Underworld. But after Inanna reaches the Underworld, she is not allowed to return and dies. However, through the divine intervention of the God Enki, her father, she is brought back to life, but needs to find replacement for herself. She chooses her beloved Dumuzid, who, in her absence, has usurped her throne. Eventually, Dumuzid too is allowed to return to earth, but only in spring and summer; in autumn, he must die again (Reichard, 2013).

Another version of this story was re-enacted in Ancient Egypt, in the persons of Isis, Horus and Osiris. And in Ancient Greece, in the story of Persephone and Demeter (mother and daughter), complete with the same ending and partial resurrection. And again, most notably, in Christianity, in the story of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, who both anoints Jesus and finds him resurrected.

So we see some of the same themes that we have encountered before being mentioned in the article above, i.e., the Tree of Life, resurrection, seasonal renewal and descents into the underworld. Moreover, the stories associated with Inanna seem also to be associated with Isis, Persephone and Demeter. We know from the C's that Egypt derived its civilisation from Mesopotamia when a group of sumerians migrated to Egypt, so we must assume that Inanna was on first base and the stories of Isis, Osirus and Horus merely derive from older legends rooted in Sumeria, which in turn are connected with the Annunaki, the pantheon of gods headed by Anu, Enlil and Enki.

So we see some of the same themes that we have encountered before being mentioned in the article above, i.e., the Tree of Life, resurrection, seasonal renewal and descents into the underworld. Moreover, the stories associated with Inanna seem also to be associated with Isis, Persephone and Demeter. We know from the C's that Egypt derived its civilisation from Mesopotamia when a group of sumerians migrated to Egypt, so we must assume that Inanna was on first base and the stories of Isis, Osirus and Horus merely derive from older legends rooted in Sumeria, which in turn are connected with the Annunaki, the pantheon of gods headed by Anu, Enlil and Enki.

Turning to Wikipedia, we learn of other aspects of the Inanna story:

Inanna appears in more myths than any other Sumerian deity. Many of her myths involve her taking over the domains of other deities. She was believed to have stolen the mes, which represented all positive and negative aspects of civilization, from Enki, the god of wisdom. She was also believed to have taken over the Eanna temple from An, the god of the sky. Alongside her twin brother Utu (later known as Shamash - a sun god), Inanna was the enforcer of divine justice; she destroyed Mount Ebih for having challenged her authority, unleashed her fury upon the gardener Shukaletuda after he raped her in her sleep, and tracked down the bandit woman Bilulu and killed her in divine retribution for having murdered Dumuzid. In the standard Akkadian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Ishtar asks Gilgamesh to become her consort. When he refuses, she unleashes the Bull of Heaven, resulting in the death of Enkidu and Gilgamesh's subsequent grapple with his mortality.

Inanna/Ishtar's most famous myth is the story of her descent into and return from Kur, the Ancient Mesopotamian underworld, a myth in which she attempts to conquer the domain of her older sister Ereshkigal, the queen of the underworld, but is instead deemed guilty of hubris by the seven judges of the underworld and struck dead. Three days later, Ninshubur pleads with all the gods to bring Inanna back, but all of them refuse her except Enki, who sends two sexless beings to rescue Inanna. They escort Inanna out of the underworld, but the galla, the guardians of the underworld, drag her husband Dumuzid down to the Underworld as her replacement. Dumuzid is eventually permitted to return to heaven for half the year while his sister Geshtinanna remains in the underworld for the other half, resulting in the cycle of the seasons.

As to her origins, Inanna has posed a problem for many scholars of ancient Sumer due to the fact that her sphere of power contained more distinct and contradictory aspects than that of any other deity. Two major theories regarding her origins have been proposed. The first explanation holds that Inanna is the result of a syncretism between several previously unrelated Sumerian deities with totally different domains. The second explanation holds that Inanna was originally a Semitic deity who entered the Sumerian pantheon after it was already fully structured, and who took on all the roles that had not yet been assigned to other deities.

As to her husband Dumuzid, (Sumerian: 𒌉𒍣𒉺𒇻, romanised: Dumuzid sipad) or Dumuzi, later known by the alternative form Tammuz, he is an ancient Mesopotamain god associated with shepherds. So we find the shepherd theme cropping up again.

What is clear is that Inanna only took on more prominence once Sargon the Great (who may have been the original Moses like liberator of the captive Scythian-semitic people) came to power. Since he was a Scythian-Celt and not an indigenous Sumerian, this may suggest that she was a Semitic deity who perhaps have had her roots in even older Celtic mother goddess deities.

With the seven judges of the underworld (also seen in Mayan myths) we see another connection with the number seven, which could relate to the seven chakras, the seven ruling planets and possibly to the 'Court of Seven' mentioned by the C's.

Inanna/Ishtar's most famous myth is the story of her descent into and return from Kur, the Ancient Mesopotamian underworld, a myth in which she attempts to conquer the domain of her older sister Ereshkigal, the queen of the underworld, but is instead deemed guilty of hubris by the seven judges of the underworld and struck dead. Three days later, Ninshubur pleads with all the gods to bring Inanna back, but all of them refuse her except Enki, who sends two sexless beings to rescue Inanna. They escort Inanna out of the underworld, but the galla, the guardians of the underworld, drag her husband Dumuzid down to the Underworld as her replacement. Dumuzid is eventually permitted to return to heaven for half the year while his sister Geshtinanna remains in the underworld for the other half, resulting in the cycle of the seasons.

As to her origins, Inanna has posed a problem for many scholars of ancient Sumer due to the fact that her sphere of power contained more distinct and contradictory aspects than that of any other deity. Two major theories regarding her origins have been proposed. The first explanation holds that Inanna is the result of a syncretism between several previously unrelated Sumerian deities with totally different domains. The second explanation holds that Inanna was originally a Semitic deity who entered the Sumerian pantheon after it was already fully structured, and who took on all the roles that had not yet been assigned to other deities.

As to her husband Dumuzid, (Sumerian: 𒌉𒍣𒉺𒇻, romanised: Dumuzid sipad) or Dumuzi, later known by the alternative form Tammuz, he is an ancient Mesopotamain god associated with shepherds. So we find the shepherd theme cropping up again.

What is clear is that Inanna only took on more prominence once Sargon the Great (who may have been the original Moses like liberator of the captive Scythian-semitic people) came to power. Since he was a Scythian-Celt and not an indigenous Sumerian, this may suggest that she was a Semitic deity who perhaps have had her roots in even older Celtic mother goddess deities.

With the seven judges of the underworld (also seen in Mayan myths) we see another connection with the number seven, which could relate to the seven chakras, the seven ruling planets and possibly to the 'Court of Seven' mentioned by the C's.

It also interests me that Inanna is linked with the destruction of Mount Ebih and the stealing of the Mes.

The “Inanna and Ebih” poem was composed around 2300 BCE by the Sumerian poetess Enheduanna and it was rediscovered in the 20th Century. The story told in the poem can be summarized in a few lines. We read first that the Goddess Inanna is preparing to do battle against the mountain "Ebih," because the mountain “showed her no respect”. Before attacking, Inanna goes to see the God An, whom she calls “father,” apparently to ask for his help. An, however, is perplexed and Inanna decides to fight alone; eventually managing to triumph over the mountain.

I am very interested in this story since it links with a parallel story about how the god Ninurta also fought a mountain (which is a strange thing to do when you think about it) as described in the Lugal-e Mesopotamian story.

I think Mount Ebih may actually be the Great Pyramid of Giza and may suggest that the Pyramid became the scene of a battle between the gods over its control as a weapon system in ancient times. I am aiming to do an article on this in the near future, since I think it links with the Holy Grail.

As for "Mes", these have long puzzled archaeologists and historian over the years. However, in Sumerian mythology, a me (𒈨; Sumerian: me; Akkadian: paršu) is taken to be one of the decrees of the divine that is foundational to those social institutions, religious practices, technologies, behaviors, mores, and human conditions that make civilization, as the Sumerians understood it, possible. "The Mes were therefore documents or tablets, which were effectively blueprints for civilisation… They tend to put me in mind of the Ten Commandments that in the Bible were the commandments of God recorded on tablets of stone by Moses. They also remind me to some extent of the Emerald Tablets of Thoth, the Egyptian god of wisdom later rebranded as Hermes by the Greeks and hence the source of hermetic wisdom.

It was the Sumerian deity Enki who was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization. He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity. However, Inanna tricked the god of culture, Enki, who was worshipped in the city of Eridu, into giving her the Mes. Inanna traveled to Enki's city Eridu, and by getting him drunk, she got him to give her hundreds of these Mes, which she took to her city of Uruk. Later, when sober, Enki sent mighty Abgallu (sea monsters, from ab, sea or lake + gal, big + lu, man) to stop her boat as it sailed the Euphrates and retrieve his gifts, but she escaped with the Mes and brought them to her city. Sea monsters hmmm... Leviathan maybe or the Kraken of Andromeda fame?

I think Mount Ebih may actually be the Great Pyramid of Giza and may suggest that the Pyramid became the scene of a battle between the gods over its control as a weapon system in ancient times. I am aiming to do an article on this in the near future, since I think it links with the Holy Grail.

As for "Mes", these have long puzzled archaeologists and historian over the years. However, in Sumerian mythology, a me (𒈨; Sumerian: me; Akkadian: paršu) is taken to be one of the decrees of the divine that is foundational to those social institutions, religious practices, technologies, behaviors, mores, and human conditions that make civilization, as the Sumerians understood it, possible. "The Mes were therefore documents or tablets, which were effectively blueprints for civilisation… They tend to put me in mind of the Ten Commandments that in the Bible were the commandments of God recorded on tablets of stone by Moses. They also remind me to some extent of the Emerald Tablets of Thoth, the Egyptian god of wisdom later rebranded as Hermes by the Greeks and hence the source of hermetic wisdom.

It was the Sumerian deity Enki who was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization. He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity. However, Inanna tricked the god of culture, Enki, who was worshipped in the city of Eridu, into giving her the Mes. Inanna traveled to Enki's city Eridu, and by getting him drunk, she got him to give her hundreds of these Mes, which she took to her city of Uruk. Later, when sober, Enki sent mighty Abgallu (sea monsters, from ab, sea or lake + gal, big + lu, man) to stop her boat as it sailed the Euphrates and retrieve his gifts, but she escaped with the Mes and brought them to her city. Sea monsters hmmm... Leviathan maybe or the Kraken of Andromeda fame?

Here is a supposed list of the Mes:

- ENship.

- Godship.

- The exalted and enduring crown.

- The throne of kingship.

- The exalted sceptre.

- The royal insignia.

- The exalted shrine.

- Shepherdship.

The Enuma Elish

However, could they have had another more technical meaning suggesting high technology? In the story of Marduk in the Enuma Elish. The Enuma Elish (also known as The Seven Tablets of Creation) is the Mesopotamian creation myth. The myth tells the story of the great god Marduk's victory over the forces of chaos and his establishment of order at the creation of the world. All of the tablets containing the myth, found at Ashur, Kish, Ashurbanipal's library at Nineveh, Sultantepe, and other excavated sites, date to c. 1200 BC but their colophons indicate that these are all copies of a much older version of the myth dating from long before the fall of Sumer in c. 1750 BC. So the Enuma Elish may be one of the oldest stories in the world.

These Seven Tablets of Creation may also link with the Tablet of Destinie. In Mesopotamian mythology, the Tablet of Destinies (Sumerian: 𒁾𒉆𒋻𒊏 dub namtarra; Akkadian: ṭup šīmātu, ṭuppi šīmāti) was envisaged as a clay tablet inscribed with cuneiform writing, also impressed with cylinder seals, which, as a permanent legal document, conferred upon the god Enlil his supreme authority as ruler of the universe. In the Sumerian poem Ninurta and the Turtle it is the god Enki, rather than Enlil, who holds the Tablet, as Enki has stolen it and brought it to the Abzu. Both this poem and the Akkadian Anzû poem also share concern of the theft of the tablet by the bird Imdugud (Sumerian) or Anzû (Akkadian). In the Babylonian Enuma Elish, Tiamat bestows this tablet on Kingu and gives him command of her army. In the end, the Tablet always returns to Enlil.

I wonder if there is any connection between the 'Tablet of Destinies' and the Spear of Destiny, which could have been Jacob's Pillar? if so, is there any connection also to the Holy Grail, the Merkabah or Matriarch Stone?

The Enuma Elish and the Bible

The Enuma Elish would later be the inspiration for the Hebrew scribes who created the text now known as the biblical Book of Genesis. Prior to the 19th century CE, the Bible was considered the oldest book in the world and its narratives were thought to be completely original. In the mid-19th century CE, however, European museums, as well as academic and religious institutions, sponsored excavations in Mesopotamia to find physical evidence for historical corroboration of the stories in the Bible. These excavations found quite the opposite, however, in that, once cuneiform was translated, it was understood that a number of biblical narratives were Mesopotamian in origin.

In revising the Mesopotamian creation story for their own ends, the Hebrew scribes tightened the narrative and the focus but retained the concept of the all-powerful deity who brings order from chaos. Marduk, in the Enuma Elish, establishes the recognizable order of the world - just as God does in the Genesis tale - and human beings are expected to recognize this great gift and honour the deity through service. In Mesopotamia, in fact, it was thought that humans were co-workers with the gods to maintain the gift of creation and keep the forces of chaos at bay.

Marduk

Marduk gained prominence in Babylon during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC) and superseded the popular goddess Inanna in worship. During Hammurabi's reign, in fact, a number of previously popular female deities were replaced by male gods. The Enuma Elish, praising Marduk as the most powerful of all the gods, therefore became increasingly popular as the god himself rose in prominence and his city of Babylon grew in power.

Hence, the replacement of female deities by male gods seems to date from this period with the rise of Babylon.

These Seven Tablets of Creation may also link with the Tablet of Destinie. In Mesopotamian mythology, the Tablet of Destinies (Sumerian: 𒁾𒉆𒋻𒊏 dub namtarra; Akkadian: ṭup šīmātu, ṭuppi šīmāti) was envisaged as a clay tablet inscribed with cuneiform writing, also impressed with cylinder seals, which, as a permanent legal document, conferred upon the god Enlil his supreme authority as ruler of the universe. In the Sumerian poem Ninurta and the Turtle it is the god Enki, rather than Enlil, who holds the Tablet, as Enki has stolen it and brought it to the Abzu. Both this poem and the Akkadian Anzû poem also share concern of the theft of the tablet by the bird Imdugud (Sumerian) or Anzû (Akkadian). In the Babylonian Enuma Elish, Tiamat bestows this tablet on Kingu and gives him command of her army. In the end, the Tablet always returns to Enlil.

I wonder if there is any connection between the 'Tablet of Destinies' and the Spear of Destiny, which could have been Jacob's Pillar? if so, is there any connection also to the Holy Grail, the Merkabah or Matriarch Stone?

The Enuma Elish and the Bible

The Enuma Elish would later be the inspiration for the Hebrew scribes who created the text now known as the biblical Book of Genesis. Prior to the 19th century CE, the Bible was considered the oldest book in the world and its narratives were thought to be completely original. In the mid-19th century CE, however, European museums, as well as academic and religious institutions, sponsored excavations in Mesopotamia to find physical evidence for historical corroboration of the stories in the Bible. These excavations found quite the opposite, however, in that, once cuneiform was translated, it was understood that a number of biblical narratives were Mesopotamian in origin.

In revising the Mesopotamian creation story for their own ends, the Hebrew scribes tightened the narrative and the focus but retained the concept of the all-powerful deity who brings order from chaos. Marduk, in the Enuma Elish, establishes the recognizable order of the world - just as God does in the Genesis tale - and human beings are expected to recognize this great gift and honour the deity through service. In Mesopotamia, in fact, it was thought that humans were co-workers with the gods to maintain the gift of creation and keep the forces of chaos at bay.

Marduk

Marduk gained prominence in Babylon during the reign of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC) and superseded the popular goddess Inanna in worship. During Hammurabi's reign, in fact, a number of previously popular female deities were replaced by male gods. The Enuma Elish, praising Marduk as the most powerful of all the gods, therefore became increasingly popular as the god himself rose in prominence and his city of Babylon grew in power.

Hence, the replacement of female deities by male gods seems to date from this period with the rise of Babylon.

Debra Lynn

Jedi

Hi MJF

I have a question that may be related to the bloodlines but I am not sure. I'm not even sure how to go about researching this. In the session from 5-30-09 the C's said that the earliest "Christ" was a woman. My thinking on this is that it would be nice to acknowledge her by at least knowing her name and a bit about her. Then while reading Laura's new book I came across this: A.J. Gordon wrote "It is evident that the Holy Spirit made this woman Priscilla a teacher of teachers." She was talking about the Priscilla from the new Testament who some say wrote Hebrews. pg. 82-83.

So my thoughts are swirling around this question and I started thinking 'oh, this must of been Laura in a previous life or however one want's to define the process. Is this something in the bloodline you are speaking of that might enable the 'spirit' to connect more deeply than others and then being STO orientated begin to branch outwards into questioning and then teaching? I hope this is making sense.

Reading the Romantic books and in the thread it seems we are beginning to understand and 'connect' with the other. Perhaps bringing forth the 'child' of that understanding. The Trinity. I'm not sure that connection will mean we will be hermaphrodite's if we are able to cross over into 4D as you suggested, but that there might be a higher or deeper meaning to all of that. Building a bridge of our combined energies to enable us to cross into that realm. If we can. I may be way off base here though. Still reading Laura's book and thinking about many things.

Sorry if this is bit jumbled up. How would you research this? (when you have time, no hurry)

I have a question that may be related to the bloodlines but I am not sure. I'm not even sure how to go about researching this. In the session from 5-30-09 the C's said that the earliest "Christ" was a woman. My thinking on this is that it would be nice to acknowledge her by at least knowing her name and a bit about her. Then while reading Laura's new book I came across this: A.J. Gordon wrote "It is evident that the Holy Spirit made this woman Priscilla a teacher of teachers." She was talking about the Priscilla from the new Testament who some say wrote Hebrews. pg. 82-83.

So my thoughts are swirling around this question and I started thinking 'oh, this must of been Laura in a previous life or however one want's to define the process. Is this something in the bloodline you are speaking of that might enable the 'spirit' to connect more deeply than others and then being STO orientated begin to branch outwards into questioning and then teaching? I hope this is making sense.

Reading the Romantic books and in the thread it seems we are beginning to understand and 'connect' with the other. Perhaps bringing forth the 'child' of that understanding. The Trinity. I'm not sure that connection will mean we will be hermaphrodite's if we are able to cross over into 4D as you suggested, but that there might be a higher or deeper meaning to all of that. Building a bridge of our combined energies to enable us to cross into that realm. If we can. I may be way off base here though. Still reading Laura's book and thinking about many things.

Sorry if this is bit jumbled up. How would you research this? (when you have time, no hurry)

The 'Was' also represented a form of shepherd's staff or even a long wand such as that carried by a wizard (from the Egyptian "Vizier") or druid priest, as typified by the character of Gandalf in Tolkein's Lord of the Rings. Apparently, Gandalf in Norse; IPA: [gand:alf] means "Elf of the Wand" or "Wand-elf". Usually these priests wore white robes whatever culture they would appear in. Hence, we might be seeing here an ancient great white brotherhood operating across time and cultures having arcane, esoteric and occult knowledge, which they only disclosed to those judged worthy.

Was sceptres were depicted as being carried by gods, pharaohs, and priests. In later use, it was a symbol of control over the force of chaos that Set represented.

On this last point, one of the Pharaoh's sacred roles was to preserve the kingdom from chaos and keep the state of Ma’at or balance/order. Ma’at is constantly threatened by "isfet" (disorder, injustice, lie), and it was Pharaoh’s role to dispel isfet in order to give room to ma’at.

Unfortunately, this is what Akhenaten failed to do and so he paid the ultimate price for it. Here is what the C's had to say about him in the Session dated 3 July 1999:

Q: What happened to Akhenaten? He also brought about the monotheistic worship and was apparently so hated that any mention of him, his very name, was stricken from buildings and statuary; his tomb was defaced and there was tremendous turmoil in the land. He essentially disappeared from the landscape, erased by the people who must have really hated him. What was the deal with Akhenaten?Was sceptres were depicted as being carried by gods, pharaohs, and priests. In later use, it was a symbol of control over the force of chaos that Set represented.

On this last point, one of the Pharaoh's sacred roles was to preserve the kingdom from chaos and keep the state of Ma’at or balance/order. Ma’at is constantly threatened by "isfet" (disorder, injustice, lie), and it was Pharaoh’s role to dispel isfet in order to give room to ma’at.

Unfortunately, this is what Akhenaten failed to do and so he paid the ultimate price for it. Here is what the C's had to say about him in the Session dated 3 July 1999:

A: Is not that enough? Must one endure anymore?

Q: Endure anymore what?

A: Vilification.

Q: Why was Akhenaten portrayed in images as a rather feminine individual? Did he have a congenital disease? Was he a hermaphrodite? Was he an alchemical adept who had gone through the transformation?

A: None of these.

Q: What was the reason for his strange physical appearance; his feminine hips and belly and strangely elongated face...

A: Depictions.

Q: So this was NOT how he really looked?

A: Not really.

Q: Did he choose to be depicted this way?

A: No.

Q: Was he depicted this way later as an insult?

A: Closer.

I recently came across an article written from a Jewish perspective that analysed the role of the Pharaoh within Egyptian society, which goes into more detail about his role in preserving Ma'at or balance/order. It also makes mention of Akhenaten.

Pharaoh's Divine Role in Maintaining Ma'at (Order)

Professor Jan AssmannEditor’s Preface: Most Jews with some traditional education have heard that Pharaoh saw himself as a god. The Bible never states this explicitly, but the midrash makes much of this. Most famously, Rashi offers the following interpretation of Exodus 7:15,[1] to explain why God tells Moses to meet Pharaoh by the Nile in the morning:

הנה יצא המימה – לנקביו, שהיה עושה עצמו אלוה ואומר שאינו צריך לנקביו ומשכים ויוצא לנילוס ועושה שם צרכיו:

“As he is coming out to the water” – to relieve himself. He made himself out to be a god and said that he had no need to relieve himself. Therefore, he woke early in the morning and went out to the Nile to relieve himself.

This is clearly polemical satire. How would the Egyptians themselves have understood Pharaoh’s divinity?

Pharaoh’s Role as the Son of the God Ra

The Egyptian world is founded on two basic assumptions that are both overturned by biblical monotheism.The first is the conviction that ma’at, the Egyptian concept and personification of truth, justice, social order and harmony, as well as political success and natural fertility are dependent on the state, i.e., on Pharaoh and his permanent communication with the divine world. Pharaoh, himself a god, was regarded as the son of the supreme deity and given the name, “son of Ra,” and thus incorporated the link between heaven and earth.

According to one text (of canonical normativity), the sun and creator god, Ra:

has placed the king on earth

for ever and ever,

in order that he may judge mankind and satisfy the gods;

establish Ma’at and annihilate Isfet

giving offerings to the gods and funerary offerings to the dead.[2]

Ma’at is constantly threatened by isfet (disorder, injustice, lie), and it is Pharaoh’s role to dispel isfet in order to give room to ma’at. This means: no justice, truth, or harmony is possible on earth without Pharaoh, i.e., the state.

In religious ceremonies, Pharaoh played the role of son to all the gods and goddesses in the Egyptian pantheon, his putative mothers and fathers.[3] He entered this genealogy with coronation, part of which was a ritual enactment of his divine descent. The Egyptian gods were not just a loose assembly but a structured pantheon ruled by a supreme god, the sun, from whom not only all the gods but the entire universe originated. The work of maintenance that the sun god (Ra) exerts in the sky by distributing light and ma’at in the cosmos is mirrored on earth by Pharaoh’s establishing ma’at and dispelling isfet.

The Torah’s Polemic against Sacral Kingship

The concepts of revelation, covenant and faith or loyalty, which the book of Exodus expounds in the form of narrative, represent the exact opposite of this system of sacral kingship, placing the people in direct contact and even permanent symbiosis with God, ruling out any form of political mediation. It is true that in some Psalms, in Jewish messianism, and in the later Christian and Muslim reception history of the biblical monotheism, traces of the political theology of sacral kingship survive this revolution/revelation, but in the Torah – and this is what interests us here – revolutionary concepts of covenant and revelation appear in all their radical power.

In the biblical picture, Pharaoh is deprived of his divinity and appears as a tyrant of grotesque hubris. By portraying Pharaoh as ineffectual again and again, the biblical picture denies Pharaoh’s divinity.

This biblical picture contrasts sharply with the Egyptian concept of sacral kingship, in which Pharaoh does not act on his own account but as deputy, representative, son, and image of the creator whose cosmic work of creation and maintenance he executes on the “earth of the living” and to whom he remains responsible. If he fails in this task, the gods will turn their back on Egypt.

In the biblical picture, Pharaoh is deprived of his divinity and appears as a tyrant of grotesque hubris. By portraying Pharaoh as ineffectual again and again, the biblical picture denies Pharaoh’s divinity.

This biblical picture contrasts sharply with the Egyptian concept of sacral kingship, in which Pharaoh does not act on his own account but as deputy, representative, son, and image of the creator whose cosmic work of creation and maintenance he executes on the “earth of the living” and to whom he remains responsible. If he fails in this task, the gods will turn their back on Egypt.

The Egyptians believed that they experienced this during Akhenaton’s monotheistic revolution. Thus writes Tutankhamun in retrospect on his Restoration Stela:

The land was in grave ailment,

The gods had turned their backs on this land.[4]

The Dependence of the World

on the State-Run Rituals

The second conviction of the ancient Egyptians assumed that the world is permanently threatened by collapse and its continuance is dependent on ritual action. Thus, we read in another text:

If the loaves are few on their altars,

the same will happen in the whole land

and few will be the food for the living.

If the libations are discontinued,

the inundation will fail in its source

<…> and famine will reign in the country.

If the ceremonies for Osiris are neglected <…>

the country will be deprived of its laws.

<…> the foreign countries will rebel against Egypt

and civil war and revolution will rise in the whole country.

In the Torah, ritual also plays an important role. But it has nothing to do with maintaining cosmic and social order. Both depend on God’s will rather than human action.

The Tension over Sacral Kingship through Time

Both Egyptian convictions — sacral kingship and the world-maintaining nature of ritual — have proved to be deeply rooted in human mentality. This explains the strong biblical – or, to be more precise, the Deuteronomistic – attack on them. But this polemic was not fully successful, and the ideas of sacral kingship surfaced again and again in Christian and Islamic history. But the Deuteronomist resistance to kingship persisted in places, especially in Protestant movements such as English puritanism, culminating in the public execution of Charles I of England 1647.

· He is citing the same tradition as found in Exodus Rabbah 8:9 and other places.

· Jan Assmann: Der König als Sonnenpriester. Ein kosmographischer Begleittext zur kultischen Sonnenhymnik in thebanischen Tempeln und Gräbern (= Abhandlungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo, Bd. 7). Glückstadt 1970; Jan Assmann, Ma’at. Gerechtigkeit und Unsterblichkeit im alten Ägypten (München: C.H. Beck, 1990), 205-212.

· Mia Rikala: "Sacred Marriage in the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: Circumstantial Evidence for a Ritual Interpretation,” in: Sacred Marriages, The Divine-Human Sexual Metaphor from Sumer to Early Christianity (eds. M.Nissinen/R. Uro (Hg.); Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2008), 115-144.

· Wolfgang Helck: Urkunden der 18. Dynastie. Abteilung IV, Heft 22: Inschriften der Könige von Amenophis III. bis Haremhab und ihrer Zeitgenossen. Berlin 1958, S. 2027.

I would just add that I think it is fair to say that throughout their history, whether as the Children of Israel or later as the Jewish people, the Jews have never really been big on kings, which is exemplified by the general contempt the Jewish people had for their last line of kings from the Herodian dynasty. See Herodian Kingdom of Judea - Wikipedia.

To better understand the concept of ma'at look at the depictions of the Egyptian godess:

Her symbol is an ostrich feather, which she wears on her head.

Stand upright, arms down on the body and concentrate on the central axis running through your body from beneath the soles of your feet up to over your head.

Try to stand still as much as possible.

Notice, that it is not possible.

Your body will always slightly move, like reed swayed by the wind, to hold balance.

Now imagine, that you would have an ostrich feather on your head like Ma'at and how every slight move of your body would be seen through the succussions of the feather.

Her symbol is an ostrich feather, which she wears on her head.

Stand upright, arms down on the body and concentrate on the central axis running through your body from beneath the soles of your feet up to over your head.

Try to stand still as much as possible.

Notice, that it is not possible.

Your body will always slightly move, like reed swayed by the wind, to hold balance.

Now imagine, that you would have an ostrich feather on your head like Ma'at and how every slight move of your body would be seen through the succussions of the feather.

You make a very good connection here. It makes me think of the old deportment lessons given to young ladies where they were required to balence a book on their heads without dropping it, to encourage them to walk more elegantly.To better understand the concept of ma'at look at the depictions of the Egyptian godess:

View attachment 45970

Her symbol is an ostrich feather, which she wears on her head.

Stand upright, arms down on the body and concentrate on the central axis running through your body from beneath the soles of your feet up to over your head.

Try to stand still as much as possible.

Notice, that it is not possible.

Your body will always slightly move, like reed swayed by the wind, to hold balance.

Now imagine, that you would have an ostrich feather on your head like Ma'at and how every slight move of your body would be seen through the succussions of the feather.

It is interesting too that you mention the concentration on the central axis running through the body since that is represented in the torso by the spinal column, along which the seven chakras are connected, ending with the crown chakra above the head (third eye). The kundalini awakening would see all seven chakras acting in perfect balance together. The Freemasons represent this idea of balance with the plumb line.

It also explains why eastern mystics adopt the lotus position (as per the Buddha) and seek to keep perfectly still when meditating.

Of course, with the Pharaoh, the concept of balance or order extended to the whole kingdom of Egypt and was not just a personal thing.

John Dee and the 13 Crystal Skulls

The painting certainly makes Dee look every bit the magus or magician at the court performing his conjuring tricks.

For those not familiar with Perceval, here is a brief description of the tale:

Session dated 5 July 1997:

Q: Okay. I am not going to get into all of this, but I would like to know the significance of the Fisher King?

A: Do you mean of the person or of the designation?

Q: The designation, first.

A: The one who resides within a circular continuum.

Q: What about the significance of the person?

A: Transcendental.

Q: What is a circular continuum?

A: Trapped within the grasp of one's own significance, to the exclusion of the acquisition of a broader knowledge base and understanding."

The Triple Goddess

[MJF: With all these references, are we really just seeing echoes of Hagar/Kore and Nefertiti/Sarah? Is there also a hint here that the Holy Grail may be a three faced crystal skull, as was suggested for Baphomet by Philip Gardiner and Gary Osborn?]

Modern Wicca Traditions

If the Holy Grail is in fact a pure crystal skull, then this picture of John Dee performing some magic trick or scientific experiment at the Court of Queen Elizabeth takes on a very different perspective. We must also ask what is that the artist was seeking to convey here.

The painting certainly makes Dee look every bit the magus or magician at the court performing his conjuring tricks.

The painting was executed by the British artist Henry Gillard Glindoni (1852-1913). It imagines a scene with Elizabeth visiting Dee’s house in Mortlake. To her left are her chief adviser William Cecil and her favoured courtier Sir Walter Raleigh. Seated behind Dee is his trance medium, or scryer, Edward Kelley, who is wearing a long skullcap to conceal the fact that his ears had been cut off as a punishment for his youthful crimes.

However, it is the X-ray version of the painting that gives us an additional perspective when you see Dee seemingly surrounded by a circle of human skulls. Why Glindoni painted them out is unknown. Perhaps he had to make it look like what we now see, which is august and serious, from what it was, which was occult and spooky on the instructions of the person who commissioned the work. Alternatively, did the patron realise Glindoni was hinting at something that should remain hidden and asked him to paint over it?

Glindoni's (original name ‘Glindon’ - an Irish name) speciality was that of 17th and 18th century costume and he was noted for his paintings of Cardinals. He frequently exhibited between 1872 and 1904, at the Royal Academy. He was accepted as a full member of the Royal Society of British Artists in 1879.

However, it is the X-ray version of the painting that gives us an additional perspective when you see Dee seemingly surrounded by a circle of human skulls. Why Glindoni painted them out is unknown. Perhaps he had to make it look like what we now see, which is august and serious, from what it was, which was occult and spooky on the instructions of the person who commissioned the work. Alternatively, did the patron realise Glindoni was hinting at something that should remain hidden and asked him to paint over it?

Glindoni's (original name ‘Glindon’ - an Irish name) speciality was that of 17th and 18th century costume and he was noted for his paintings of Cardinals. He frequently exhibited between 1872 and 1904, at the Royal Academy. He was accepted as a full member of the Royal Society of British Artists in 1879.

As the person who posted this image noted, there are five skulls in front of him and three behind him. Three plus five make eight and the numbers 3, 5 and 8 from part of the Fibonacci sequence, which is reflected both in nature (the number of petals on flowers and in shell spirals) and in the golden ratio. If you add 5 and 8 together you get the next number in the Fibonacci sequence, which is 13. Hence, is the artist trying to intimate something to us here? If he had painted more of the foreground in front of Dee, would he have painted five more skulls into the picture perhaps? And what might be the significance of 13 skulls?

If you look carefully, you will see on the extreme left of the picture an ugly looking figure, which may represent a crone or an old hag (an unpleasant English expression for an old woman). This figure of an old hag has though deep occult significance and pops up in mythical tales from all over the world.

As to etymology - the term “hag” appears in Middle English, and was a shortening of “hægtesse”, an Old English term for 'witch'; similarly the Dutch heks and German Hexe are also shortenings, of the Middle Dutch haghetisse and Old High German hagzusa, respectively. All of these words are derived from the Proto-Germanic hagatusjon, which is of unknown origin; the first element may be related to the word “hedge”.

A hag, in European folklore, was an ugly and malicious old woman who practices witchcraft, with or without supernatural powers – think of the witch in Hansel and Gretel. Hags are often said to be aligned with the devil or the dead. Hags are often seen as malevolent, but may also be one of the chosen forms of shapeshifting deities, such as The Morrígan or Badb, who are seen as neither wholly benevolent nor malevolent.

The “night hag” or “old hag” is also the name given to a supernatural creature, commonly associated with the phenomenon of sleep paralysis. It is a phenomenon during which a person feels a presence of a supernatural malevolent being which immobilises the person as if sitting on their chest or the foot of their bed. This variety of hag is essentially identical to the Old English mæra — a being with roots in ancient Germanic superstition, and closely related to the Scandinavian mara. According to folklore, the Old Hag sat on a sleeper's chest and sent nightmares to him or her. When the subject awoke, he or she would be unable to breathe or even move for a short period of time.

The expression Old Hag Attack also refers to a hypnagogic state in which paralysis is present. Quite often, it is accompanied by terrifying hallucinations. When excessively recurrent, some psychiatrists and physicians consider these attacks to be a disorder. Many populations treat such incidents as part of their culture and mythological worldview, rather than any form of disease or pathology.

Hags in Irish Mythology

In Irish and Scottish mythology, the cailleach is a hag goddess concerned with creation, harvest, the weather, and sovereignty. In partnership with the goddess Bríd, she is a seasonal goddess, seen as ruling the winter months while Bríd rules the summer. In Scotland, a group of hags, known as The Cailleachan (The Storm Hags) are seen as personifications of the elemental powers of nature, especially in a destructive aspect. They are said to be particularly active in raising the windstorms of spring, during the period known as A Chailleach.

Hags as sovereignty figures abound in Irish mythology. The most common pattern is that the hag represents the barren land which the hero of the tale must approach without fear and come to love on her own terms. When the hero displays this courage, love, and acceptance of her hideous side, the sovereignty hag then reveals that she is also a young and beautiful goddess.

What is interesting here is that the hag goddess is also linked with our familiar goddess Tara (Hagar) in the form of Brid or Brigit and sometimes these hags may form a triple or group of such beings as depicted in Shakespeare’s play Macbeth (c. 1603–1607), where the main protagonist of the play encounters three witches round a cauldron. The three witches, also known as the Weird Sisters or Wayward Sisters, eventually lead Macbeth to his demise and hold a striking resemblance to the Three Fates of classical mythology. The Three Fates (particularly Atropos) are often depicted as hags. The hag is also similar to Lilith of the Torah, the Bible’s Old Testament.

Perceval and the Old Hag

However, there is one depiction of the old hag that links us directly to the Holy Grail and that is the hag in the story of Percival, as depicted in Chrétien de Troyes ‘Perceval, the Story of the Grail‘ written in the late 12th century. Perceval is the earliest recorded account of what was to become the Quest for the Holy Grail but it describes only a golden grail (a serving dish) in the central scene and does not call it "holy" and treats a lance, appearing at the same time, as equally significant. [MJF: Could this lance have been a reference to the Spear of Destiny perhaps?]

If you look carefully, you will see on the extreme left of the picture an ugly looking figure, which may represent a crone or an old hag (an unpleasant English expression for an old woman). This figure of an old hag has though deep occult significance and pops up in mythical tales from all over the world.

As to etymology - the term “hag” appears in Middle English, and was a shortening of “hægtesse”, an Old English term for 'witch'; similarly the Dutch heks and German Hexe are also shortenings, of the Middle Dutch haghetisse and Old High German hagzusa, respectively. All of these words are derived from the Proto-Germanic hagatusjon, which is of unknown origin; the first element may be related to the word “hedge”.

A hag, in European folklore, was an ugly and malicious old woman who practices witchcraft, with or without supernatural powers – think of the witch in Hansel and Gretel. Hags are often said to be aligned with the devil or the dead. Hags are often seen as malevolent, but may also be one of the chosen forms of shapeshifting deities, such as The Morrígan or Badb, who are seen as neither wholly benevolent nor malevolent.

The “night hag” or “old hag” is also the name given to a supernatural creature, commonly associated with the phenomenon of sleep paralysis. It is a phenomenon during which a person feels a presence of a supernatural malevolent being which immobilises the person as if sitting on their chest or the foot of their bed. This variety of hag is essentially identical to the Old English mæra — a being with roots in ancient Germanic superstition, and closely related to the Scandinavian mara. According to folklore, the Old Hag sat on a sleeper's chest and sent nightmares to him or her. When the subject awoke, he or she would be unable to breathe or even move for a short period of time.

The expression Old Hag Attack also refers to a hypnagogic state in which paralysis is present. Quite often, it is accompanied by terrifying hallucinations. When excessively recurrent, some psychiatrists and physicians consider these attacks to be a disorder. Many populations treat such incidents as part of their culture and mythological worldview, rather than any form of disease or pathology.

Hags in Irish Mythology

In Irish and Scottish mythology, the cailleach is a hag goddess concerned with creation, harvest, the weather, and sovereignty. In partnership with the goddess Bríd, she is a seasonal goddess, seen as ruling the winter months while Bríd rules the summer. In Scotland, a group of hags, known as The Cailleachan (The Storm Hags) are seen as personifications of the elemental powers of nature, especially in a destructive aspect. They are said to be particularly active in raising the windstorms of spring, during the period known as A Chailleach.

Hags as sovereignty figures abound in Irish mythology. The most common pattern is that the hag represents the barren land which the hero of the tale must approach without fear and come to love on her own terms. When the hero displays this courage, love, and acceptance of her hideous side, the sovereignty hag then reveals that she is also a young and beautiful goddess.

What is interesting here is that the hag goddess is also linked with our familiar goddess Tara (Hagar) in the form of Brid or Brigit and sometimes these hags may form a triple or group of such beings as depicted in Shakespeare’s play Macbeth (c. 1603–1607), where the main protagonist of the play encounters three witches round a cauldron. The three witches, also known as the Weird Sisters or Wayward Sisters, eventually lead Macbeth to his demise and hold a striking resemblance to the Three Fates of classical mythology. The Three Fates (particularly Atropos) are often depicted as hags. The hag is also similar to Lilith of the Torah, the Bible’s Old Testament.

Perceval and the Old Hag

However, there is one depiction of the old hag that links us directly to the Holy Grail and that is the hag in the story of Percival, as depicted in Chrétien de Troyes ‘Perceval, the Story of the Grail‘ written in the late 12th century. Perceval is the earliest recorded account of what was to become the Quest for the Holy Grail but it describes only a golden grail (a serving dish) in the central scene and does not call it "holy" and treats a lance, appearing at the same time, as equally significant. [MJF: Could this lance have been a reference to the Spear of Destiny perhaps?]

For those not familiar with Perceval, here is a brief description of the tale:

The poem opens with Perceval, whose mother has raised him apart from civilisation in the forests of Wales. While out riding one day, he encounters a group of knights and realises he wants to be one. Despite his mother's objections, the boy heads to King Arthur’s court, where a young girl predicts greatness for him. Sir Kay taunts him and slaps the girl, but Perceval amazes everyone by killing a knight who had been troubling King Arthur and taking his vermilion (red) armour. He then sets out for adventure. He trains under the experienced Gornemant, then falls in love with and rescues Gornemant's niece Blanchefleur. Perceval captures her assailants and sends them to King Arthur's court to proclaim Perceval's vow of revenge on Sir Kay.

Perceval remembers that his mother fainted when he went off to become a knight, and goes to visit her. During his journey, he comes across the Fisher King fishing in a boat on a river, who invites him to stay at his castle. While there, Perceval witnesses a strange procession in which young men and women carry magnificent objects from one chamber to another. First, comes a young man carrying a bleeding lance, then two boys carrying candelabra, and then a beautiful young girl emerges bearing an elaborately decorated graal, or grail. Finally, another maiden carries a silver plate (or platter or carving dish). They passed before him at each course of the meal. Perceval, who had been trained by his guardian Gornemant not to talk too much, remains silent through all of this. He wakes up the next morning alone and resumes his journey home. He encounters a girl in mourning, who admonishes him for not asking about the grail, as that would have healed the wounded king. He also learns that his mother has died.

Perceval captures another knight and sends him to King Arthur's court with the same message as before. King Arthur sets out to find Perceval and, upon finding him, attempts to convince him to join the court. Perceval unknowingly challenges Sir Kay to a fight, in which he breaks Sir Kay's arm and exacts his revenge. Perceval agrees to join the court, but soon after a loathly lady enters and admonishes Perceval once again for failing to ask the Fisher King whom the grail served.

No more is heard of Perceval except in a short later passage, in which a hermit explains that the grail contains a single mass-wafer (MJF: clearly a reference to the Holy Eucharist) that miraculously sustains the Fisher King’s wounded father. The loathly lady announces other quests that the Knight of the Round Table proceed to take up and the remainder of the poem deals with Arthur's nephew and best knight Gawain, who has been challenged to a duel by a knight who claims Gawain had slain his lord. Gawain offers a contrast and complement to Perceval's naiveté as a courtly knight having to function in un-courtly settings. An important episode is Gawain's liberation of a castle whose inhabitants include his long-lost mother and grandmother as well as his sister Clarissant, whose existence was unknown to him. This tale also breaks off unfinished.

The Loathly Lady

The motif of the loathly lady is that of a woman who appears unattractive (ugly = loathly) but undergoes a transformation upon being approached by a man in spite of her unattractiveness, becoming extremely desirable. It is then revealed that her ugliness was the result of a curse which was broken by the hero's action. The loathly lady (Welsh: dynes gas, Motif D732 in Stith Thompson's motif index), was a tale type or device commonly used in medieval literature, most famously in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Wife of Bath's Tale, in which a knight, told that he can choose whether his bride is to be ugly yet faithful, or beautiful yet false, frees the lady from the form entirely by allowing her to choose for herself. A variation on this story is attached to Sir Gawain in the related grail romances The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle and The Marriage of Sir Gawain.

Another name for a loathly lady is, of course, a hag. Hence, we see a hag appearing in the story of Perceval. However, there are three main women who appear in the Perceval grail story. The first is a beautiful young girl who carries the grail followed by another carrying a silver platter [MJF: etymologically driving from the word for “knee”]. The second is the girl in mourning, who admonishes him for not asking about the grail, as that would have healed the wounded king [MJF: was he symbolically wounded in the thigh like the Patriarch Jacob perhaps?]. The third, the hag, enters the court and admonishes Perceval once again for failing to ask the Fisher King whom the grail served. In this use of three women, we see the echo of the triple goddess theme once more. The admonishment of Perceval represents the failure of the young knight to ask the question who does the Grail serve as this would have healed Arthur the Fisher King, since, unless you ask that question, you will never escape your present 3D state and will remain in wounded blissful ignorance just like the Fisher King. To illustrate this point, here is what the C’s said about the Fisher King in the session dated 5 July 1997 session, which I quoted in the thread Session 13 March 2021 where there was a discussion about the issue of repeating time loops:

"Laura's suggestion of reading the romantic novels may help speed up the process of learning these karmic lessons in the short time we have left. Moreover, the C's have said this is the end of a grand cycle, which may well provide an opportunity for people to break out of the time loop once and for all."

Perceval remembers that his mother fainted when he went off to become a knight, and goes to visit her. During his journey, he comes across the Fisher King fishing in a boat on a river, who invites him to stay at his castle. While there, Perceval witnesses a strange procession in which young men and women carry magnificent objects from one chamber to another. First, comes a young man carrying a bleeding lance, then two boys carrying candelabra, and then a beautiful young girl emerges bearing an elaborately decorated graal, or grail. Finally, another maiden carries a silver plate (or platter or carving dish). They passed before him at each course of the meal. Perceval, who had been trained by his guardian Gornemant not to talk too much, remains silent through all of this. He wakes up the next morning alone and resumes his journey home. He encounters a girl in mourning, who admonishes him for not asking about the grail, as that would have healed the wounded king. He also learns that his mother has died.

Perceval captures another knight and sends him to King Arthur's court with the same message as before. King Arthur sets out to find Perceval and, upon finding him, attempts to convince him to join the court. Perceval unknowingly challenges Sir Kay to a fight, in which he breaks Sir Kay's arm and exacts his revenge. Perceval agrees to join the court, but soon after a loathly lady enters and admonishes Perceval once again for failing to ask the Fisher King whom the grail served.

No more is heard of Perceval except in a short later passage, in which a hermit explains that the grail contains a single mass-wafer (MJF: clearly a reference to the Holy Eucharist) that miraculously sustains the Fisher King’s wounded father. The loathly lady announces other quests that the Knight of the Round Table proceed to take up and the remainder of the poem deals with Arthur's nephew and best knight Gawain, who has been challenged to a duel by a knight who claims Gawain had slain his lord. Gawain offers a contrast and complement to Perceval's naiveté as a courtly knight having to function in un-courtly settings. An important episode is Gawain's liberation of a castle whose inhabitants include his long-lost mother and grandmother as well as his sister Clarissant, whose existence was unknown to him. This tale also breaks off unfinished.

The Loathly Lady

The motif of the loathly lady is that of a woman who appears unattractive (ugly = loathly) but undergoes a transformation upon being approached by a man in spite of her unattractiveness, becoming extremely desirable. It is then revealed that her ugliness was the result of a curse which was broken by the hero's action. The loathly lady (Welsh: dynes gas, Motif D732 in Stith Thompson's motif index), was a tale type or device commonly used in medieval literature, most famously in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Wife of Bath's Tale, in which a knight, told that he can choose whether his bride is to be ugly yet faithful, or beautiful yet false, frees the lady from the form entirely by allowing her to choose for herself. A variation on this story is attached to Sir Gawain in the related grail romances The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnelle and The Marriage of Sir Gawain.

Another name for a loathly lady is, of course, a hag. Hence, we see a hag appearing in the story of Perceval. However, there are three main women who appear in the Perceval grail story. The first is a beautiful young girl who carries the grail followed by another carrying a silver platter [MJF: etymologically driving from the word for “knee”]. The second is the girl in mourning, who admonishes him for not asking about the grail, as that would have healed the wounded king [MJF: was he symbolically wounded in the thigh like the Patriarch Jacob perhaps?]. The third, the hag, enters the court and admonishes Perceval once again for failing to ask the Fisher King whom the grail served. In this use of three women, we see the echo of the triple goddess theme once more. The admonishment of Perceval represents the failure of the young knight to ask the question who does the Grail serve as this would have healed Arthur the Fisher King, since, unless you ask that question, you will never escape your present 3D state and will remain in wounded blissful ignorance just like the Fisher King. To illustrate this point, here is what the C’s said about the Fisher King in the session dated 5 July 1997 session, which I quoted in the thread Session 13 March 2021 where there was a discussion about the issue of repeating time loops:

"Laura's suggestion of reading the romantic novels may help speed up the process of learning these karmic lessons in the short time we have left. Moreover, the C's have said this is the end of a grand cycle, which may well provide an opportunity for people to break out of the time loop once and for all."

Session dated 5 July 1997:

Q: Okay. I am not going to get into all of this, but I would like to know the significance of the Fisher King?

A: Do you mean of the person or of the designation?

Q: The designation, first.

A: The one who resides within a circular continuum.

Q: What about the significance of the person?

A: Transcendental.

Q: What is a circular continuum?

A: Trapped within the grasp of one's own significance, to the exclusion of the acquisition of a broader knowledge base and understanding."

The Grail therefore serves to dispense knowledge and wisdom allowing you to escape the circular continuum of ego in 3D reincarnation, which ties in with the kundalini awakening, the serpent fire that will trigger your dormant junk DNA and repair the DNA strands currently residing in the etheric realm. This makes sense if the Grail is a trans-dimensional crystal device such as Baphomet, the Merkabah Stone, which contact with will only serve to strengthen your abilities (see Part 2 below for more on this).

The Triple Goddess

A triple deity (sometimes referred to as threefold, tripled, triplicate, tripartite, triune or triadic, or as a trinity) is three deities that are worshipped as one. Such deities are common throughout world mythology. Carl Jung considered the arrangement of deities into triplets an archetype in the history of religion. In classical religious iconography or mythological art, three separate beings may represent either a triad who always appear as a group (Greek Moirai, Charites, Erinyes; Norse Norns; or the Irish Morrígan) or a single deity known from literary sources as having three aspects (Greek Hecate, Roman Diana. According to the linguist M. L. West, various female deities and mythological figures in Europe show the influence of pre-Indo-European goddess-worship, and triple female fate divinities, typically "spinners" of destiny, are attested all over Europe and in Bronze Age Anatolia [MJF: see also the Three Fates above.].

The Roman goddess Diana [Artemis to the Greeks] was venerated from the late sixth century BC as diva triformis, "three-form goddess", and early on was conflated with the similarly-depicted Greek goddess Hekate. Andreas Alföldi interpreted a late Republican numismatic image as Diana "conceived as a threefold unity of the divine huntress, the Moon goddess and the goddess of the nether world, “Hekate". This coin shows that the triple goddess cult image still stood in the lucus of Nemi in 43 BC. Spells and hymns in Greek magical papyri refer to the goddess (called Hecate, Persephone, and Selene, among other names) as "triple-sounding, triple-headed, triple-voiced..., triple-pointed, triple-faced, triple-necked". In one hymn, for instance, the "Three-faced Selene" is simultaneously identified as the three Charites, the three Moirai, and the three Erinyes; she is further addressed by the titles of several goddesses. Hans Dieter Betz notes: "The goddess Hekate, identical with Persephone, Selene, Artemis, and the old Babylonian goddess Ereschigal, is one of the deities most often invoked in the papyri.