A Freedom of information request submitted by our Gap legal team to Prime Minister

Scott Morrison (ScoMo)

confirms vaccinations cannot be forced on the people.

Legal maxim: “what cannot be done directly is forbidden to be done indirectly”

Meaning if the federal parliament cannot mandate vaccines neither can the states let alone employers!

Employers are walking a dangerous line.

The following is a must for all who wish that any pharmaceutical vaccine remains VOLUNTARY.

For a full write up including the text below and much more please go to this link-

https://constitutionwatch.com.au/?s=Section+51+xxiii (the link goes to a page that is run by GAP's legal team I believe)

The powers of the Commonwealth with respect to legislating on medical issues is one of the items in section 51 of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act.

(xxiiiA) the provision of maternity allowances, widows’ pensions, child endowment, unemployment, pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services (but not so as to authorize any form of civil conscription), benefits to students and family allowances;

The Constitution was amended by referendum to include this provision in 1946. Consequently, a detailed analysis of the meaning of the clause cannot be found in “the Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth by Quick & Garran.

However there is a 95 page High Court ruling on the meaning of this provision. British Medical Association v Commonwealth [1949] HCA 44; (1949) 79 CLR 201 (7 October 1949).

The two key aspects of the ruling relate to 1) the extent of powers provided to the Parliament by this provision, and 2) the meaning of “civil” conscription.

This important ruling deals with compelling a medical practitioner to render a service and more important confirms the right of a person to determine by his will if he should take any benefit provided.

In the written judgement of Latham C.J. he stated:

“The power is not a power to make law with respect to, e.g. pharmaceutical benefits and medical services. It is a power to make laws with respect to the provision of such benefits and services” (at p242)

“If a person or institutions choose to remain outside the benefits of the scheme there is not in my opinion anything in the Act to compel them to accept those benefits.” (at p244)

“(xxiiiA) relates only to the provision by the Commonwealth, and not by, e.g. doctors on private practice, of medical services.” (at p247)

“The object of conferring power upon the Commonwealth Parliament to make laws for the provision of pharmaceutical benefits was to enable the Parliament to make laws with respect to (inter alia) the provision of pharmaceutical benefits by the Commonwealth under a scheme which should involve no compulsion of service by any person which would leave every person, according to his own will, and not by reason of the exercise of the will of Parliament or of any other person, at liberty to take part in the execution of the scheme or to stand outside the scheme altogether, whether as doctor, as chemist or as patient.” (at p253)

On the subject of Civil Conscription the following was stated:

In the written judgement of McTierman J. he stated:

“The condition in par. (xxiiiA.) with respect to civil conscription is aimed at the passing of a law which by any form conscribes a person into the service of the Commonwealth.” (at p283)

In the written judgement of Williams J. he stated:

“It would equally be a form of civil conscription of medical or dental services to compel medical practitioners or dentists by law to make their professional services as civilians available to the Commonwealth or its authorities or the States or their authorities or to carry on their professions in particular localities. Conscription as a word of general application would seem to signify compulsory as opposed to voluntary service, so that the words “industrial conscription” would seem naturally to connote compulsory as opposed to voluntary employment in industry, and the expression “civil conscription of medical and dental services” naturally to connote the compulsory as opposed to the voluntary exercise of such services in civil life. Accordingly, in my opinion, the expression invalidates all legislation which compels medical practitioners or dentists to provide any form of medical or dental service.” (at p287)

In the written judgement of Webb J. he stated:

“I think the electors would have taken the proposed law to emphasize, in the use of the words “any form,” that legislation for the provision of benefits or services of the kind referred to could not authorize compulsory service of any kind, at least in the provision of medical or dental services, either independently or as incidental to pharmaceutical or other benefits, and that compulsion, to any extent or of any nature, whether legal, by the imposition of penalties, or practical, by any other means, direct or indirect, could not be authorized. To require a person to do something which he may lawfully decline to do but only at the sacrifice of the whole or a substantial part of the means of his livelihood would, I think, be to subject him to practical compulsion amounting to conscription in the case of services required by Parliament to be rendered to the people. If Parliament cannot lawfully do this directly by legal means it cannot lawfully do it indirectly by creating a situation, as distinct from merely taking advantage of one, in which the individual is left no real choice but compliance.” (at p293)

“But when this service is made compulsory by a fine, or loss of practice to avoid the fine, in the case of any patient, with few exceptions, who does not request that the Commonwealth form be not used, then, having regard not only to the extent of the professional work involved but to the almost unlimited number of persons entitled to insist on the service at any time, it becomes, I think, not merely a compulsory service but a form of civil conscription within any meaning that can be given to that expression which, if not quite clear, was certainly intended to be comprehensive. It is civil conscription of doctors as doctors. When Parliament comes between patient and doctor and makes the lawful continuance of their relationship as such depend upon a condition, enforceable by fine, that the doctor shall render the patient a special service, unless that service is waived by the patient, it creates a situation that amounts to a form of civil conscription.”(at p 295)

This civil conscription can be avoided, without any breach of the law, to the extent that the doctor vacates the field of medicine, which, however, would involve, in many if not most cases, a considerable loss of practice and of income. But it is still civil conscription. Military conscription would not cease to be such because those liable to it might avoid it by a change of occupation.” (at p295)

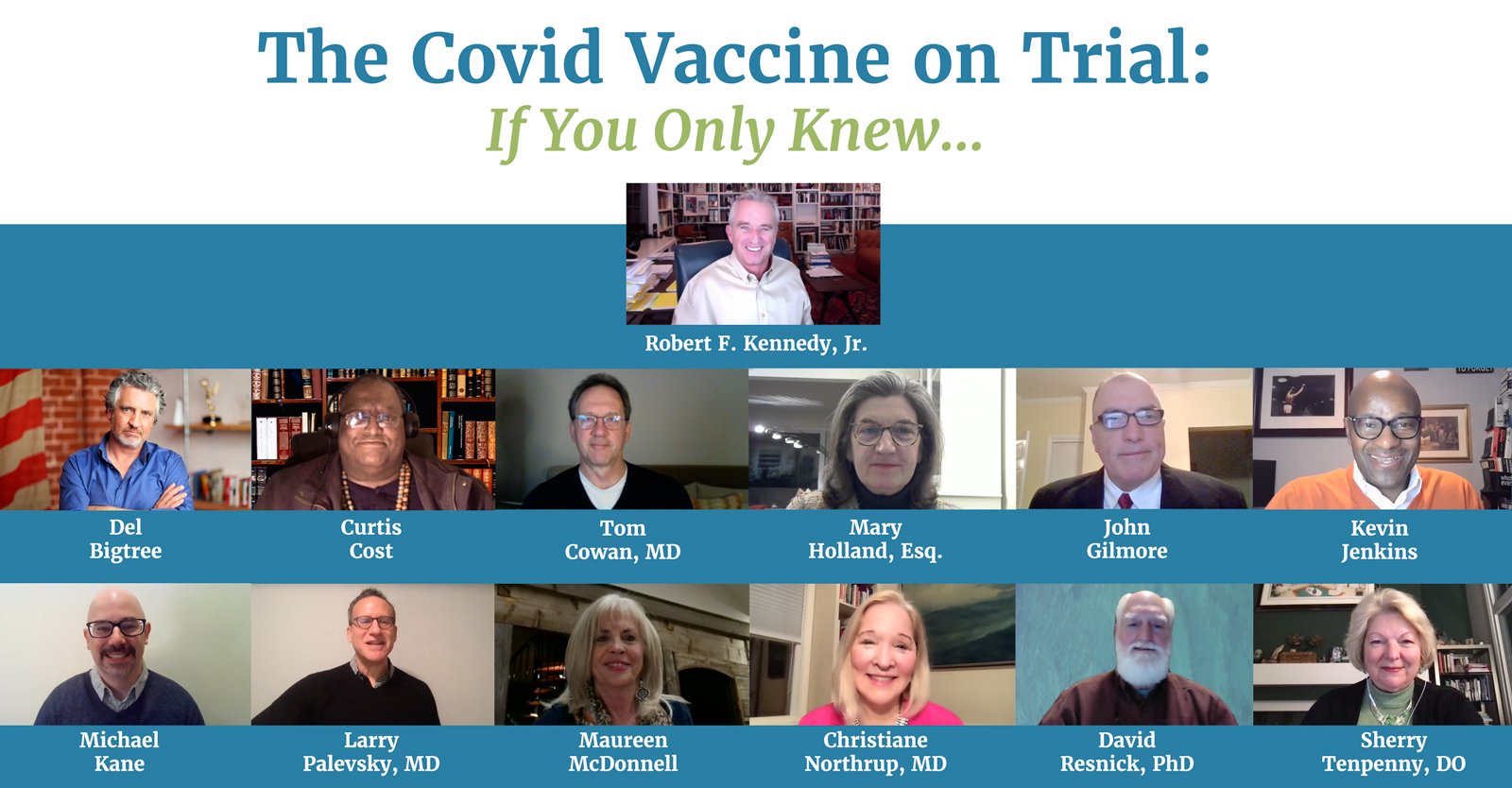

childrenshealthdefense.org

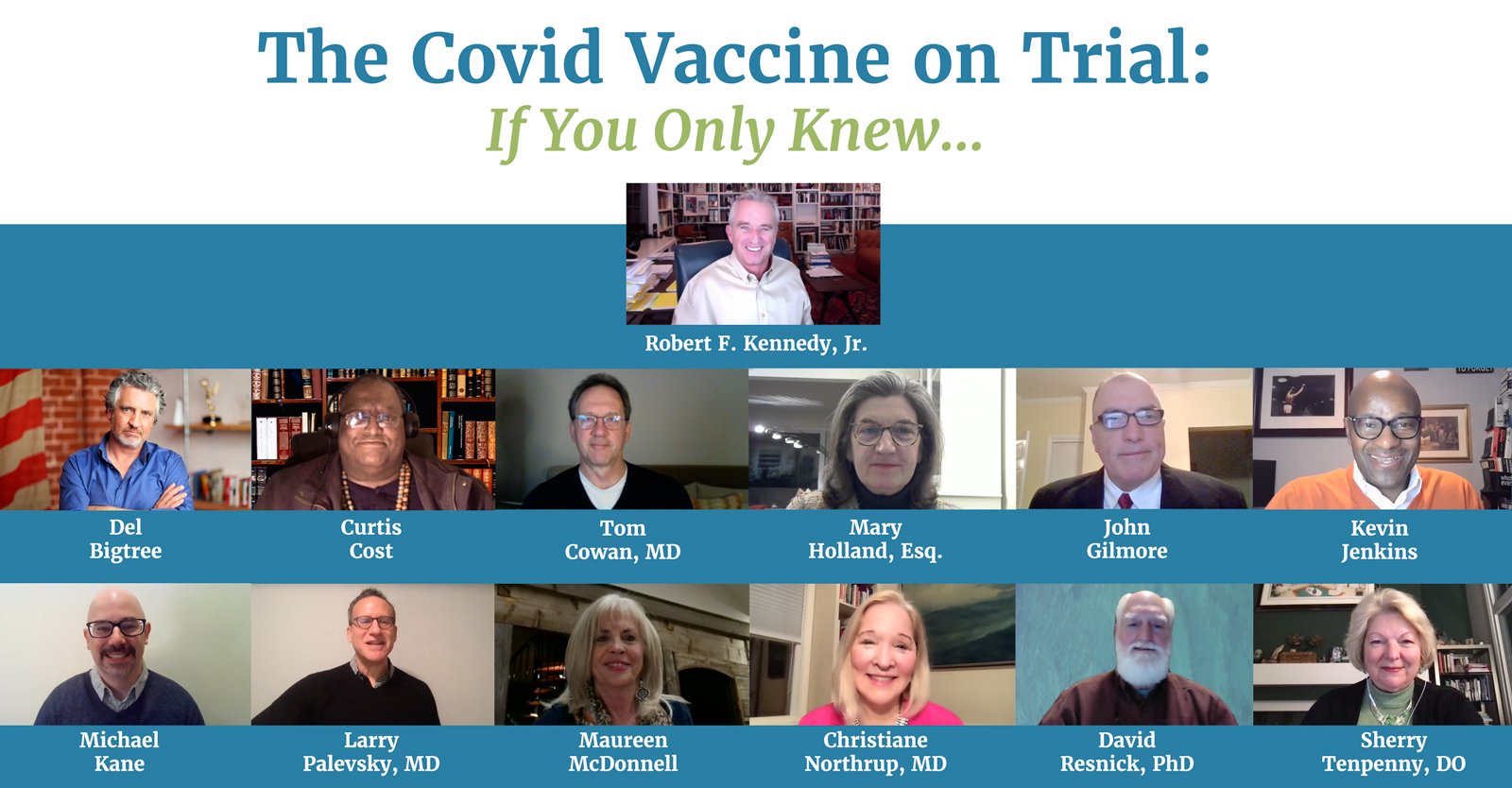

childrenshealthdefense.org